On spring weekends, garden centers are so busy that people stand in long checkout lines holding armloads of expensive seedlings and a few seed packets. Usually these buyers are making several major mistakes at once. What I’m about to tell you about those errors won’t endear me to garden center owners and makes it highly unlikely that my book will ever appear for sale in those places.Oh well ... personal honor is infinitely more valuable than bigger royalties.

Let’s take a stroll through an imaginary garden center at the peak of spring planting season and discuss what we find.

The mind is strange. I direct my magic keyboard to an imaginary North American garden center in spring, and instead I am taken to scenes from my childhood in Michigan.Winter is ending. The snow melts. The earth thaws. Some weeks later, on a sunny afternoon, I am walking along a street with my jacket unzipped, and for the first time there appears an intoxicating odor — spring. The soil has warmed up enough that I can smell the bloom of soil fungi.The nose of this spring wine is rich, fruity.When I was young and this aroma hit, some instinctual joy would grab me and I would go running down the street, block after block, fast as I could.

You’d expect on such an especially wondrous day that sedate older people would be out digging their gardens. But no, they may admire the tulips by the front door, but their backyard veggie gardens are still growing weeds instead of spinach, radishes, and peas.Weeks pass. Finally the much-spoken-of day of the last usual frost arrives.Now people mob the garden center, buy an instant garden, rush home, start up the rototiller or start digging up the backyard, and “put in the garden.”

Putting-in is usually done over one weekend, sometimes in one afternoon. Typically tomato, cabbage, broccoli, onion, lettuce, zucchini, cucumber, pumpkin, and winter squash seedlings are taken home and set out, all in a few hours. Some people even buy sweet corn as seedlings for transplanting. A few seeds are sown: carrots, beets.Oh, what joy and hope my imaginary people are feeling! But I don’t know whether to smile, laugh, or cry. I like it. I hate it.What a waste.What fun.

My emotions conflict because I know what happens next. Some of the seedlings fail to survive, so more are purchased and replanted the next weekend. Sometimes this repurchase/replanting is repeated yet again. A great deal of money is invested in this hobby garden.The folly is made worse when people buy seedlings for types of vegetables that should be started directly from seeds, but many gardeners believe it is impossible to make seeds come up.

And then what happens? All six cabbage seedlings from one little tray survive. Two months later, six heads harden on the same day, and one week after heading up, five of them, not yet cut, begin to split open. But it is too hot in high summer to make good sauerkraut, which isn’t wanted anyway. Coleslaw is what is wanted during the months of August and September. So, to make the best of it, all the neighbors or relatives get a splitting cabbage.

Broccoli? Same thing happens. Six big flowers form in the same week. This bounty gets frozen, but no one in the family likes eating frozen broccoli much. Even if they did, the variety in the tray doesn’t freeze well, so it mostly goes uneaten. After the large central flowers are cut, only a few small woody side shoots form because the variety selected was bred to be grown for the supermarket trade, to quickly produce one central flower and be done with it. A different variety could have made large succulent secondary flowers for several months after harvest of the main head.And there are varieties of cabbage bred to stand for many weeks after heading up before they split.

Luckily there will be some big successes; there are so many tomatoes to pick that the pantry is packed solid with sauce and green tomato pickles. Come the end of the season, the pantry work shelf is covered with ripening tomatoes that last into autumn.No wonder everyone loves to grow tomatoes.

And next? Next comes frost.The first light frost wipes out almost everything except the Swiss chard. And the gardeners add up what was spent and the worth of what was actually eaten or put by and wonder why they bothered. But next spring the same compulsion that makes a young man run for joy has that same person back in the garden center, doing it all over again.

The next few chapters of this book are mainly about avoiding mistakes in judgment and expanding your imagination, because the garden can be more than fun and a joy and a promoter of health and a producer of food more nutritious than could be purchased for any price — the vegetable garden can also be an astonishingly sensible economic venture. Even where the winter is hard, the garden can supply the kitchen for several more months than most people expect. But for all those good things to happen, the garden has to be given the same degree of attention that other enthusiasts give to selecting the right fishing lure, modifying their automobile, or refining their golf swing.

Can you do that? Can you give food gardening its due attention in this era of the end of oil, this time of a globalized labor pool, this season of resource hostilities? Can you afford not to? If you agree to continue along with me in this book, the first thing I’m going to do is wean you off the garden center.

Whenever I inspect vegetable transplants, I am deeply suspicious. Has the seedling been properly hardened off? Is the seedling pot-bound or the opposite, insufficiently rooted? Is the variety marked on the label useful in the home garden? Is the seedling actually the variety marked on the label? Should this species or variety even be transplanted in the first place? Let’s take up these concerns, back to front.

Should it be transplanted in the first place? Some species are extraordinarily difficult to transplant, such as beets, carrots, and chard (silverbeet). But they can look so jolly in the seedling tray! Transplanted carrots may survive to grow a top, but usually fail to make useful roots. Cucurbits (melons, pumpkins, zucchini, cucumber, squash) don’t transplant well, and if they don’t die from the attempt, their growth is usually set back so severely that seeds of the same variety sown on the same day as transplants are put out will yield just as soon or sooner. So why waste so much money? Lettuce, too, generally does better started from seed; the transplanting process hugely shocks its root system. This is also true of transplanting corn.

Is the seedling mislabeled? Unless it is a red cabbage seedling labeled as a green cabbage, you can rarely tell if the label is incorrect. But please consider this: the wise buyer always imagines the ethical temptations the seller might have and then is not surprised if a seller falls prey to moral weakness. For example, those pretty plastic labels on seedlings cost as much as or more than the seed did, especially if they carry a picture of the fruit or plant on them. The greenhouse operator may have invested in a big box of labels for some variety whose seed is not available that year.What might be done in that case? Wouldn’t it be tempting for the seed vendor to get a similar variety and substitute it? Who could tell? Or suppose the seed merchant supplying that bedding-plant raiser was out of stock on some popular variety.Wouldn’t it be tempting to make a substitution,“accidentally” mislabeling a bag? Who could tell?

If such a substitution were truly a nearly identical variety, then almost no one would notice. But what if a cabbage variety were popular because it could stand without splitting for weeks after heading up and also tasted nice? What if it were replaced with a cannery sauerkraut variety that split within days and had a texture and flavor like cardboard? That wouldn’t be so nice.

One species that isn’t likely to be mislabeled is tomatoes. That’s because people look forward to eating a familiar fruit every year. It would be hard to fool a lot of customers with tomatoes.Green bell peppers and eggplants, however, could be another matter altogether.

Is the seedling a home-garden variety in the first place?What if, in the crunch of spring, the garden center owner can’t get enough seedlings from the usual supplier and so turns in desperation to a seedling raiser supplying farmers growing for the supermarket produce department or the cannery?

What if the seedling raiser figures that corn is corn is corn and you can’t tell anything at two weeks old, so any cheap seed tossed into the trays will be suitable? What if the seedling raiser, flinching at paying several cents for each high-quality broccoli seed, offers a much cheaper variety for which the seeds cost only a few cents per hundred? What if? The result will be a broccoli patch in which about half the plants fail to make a large central head and whose flowers are coarsely, loosely budded and likely of poor flavor.

What if any or all of the above happens? Well you, the soon-to-be-disappointed customer, have invested a lot of work, fertilizer, effort, and hopes.

Is the seedling pot-bound? Ah, at last, something about transplant quality the buyer can see before purchasing. Raising transplants for profit is not easy.The seedlings rapidly grow from being too young to ethically sell to being almost too old to ethically sell in under ten days.

When they are too young, their root system has not yet filled the pot; the soil ball around the roots will not hold together when it is transplanted. Should the soil crumble away during transplanting, so much damage may be done to the delicate root hairs that even if the seedling survives, it will not grow well for a week to ten days. That’s one reason (of several) that directly seeded plants will often outgrow transplants.

When the seedling has been in its pot too long, the roots will overfill the pot.The pot-bound plant may, if fed liquid fertilizer and watered several times a day, continue growing and look okay above ground, but its roots wrap themselves around and around the inside of the pot.When the seedling is transplanted, that constrained root system can’t support the top in hot weather unless it’s watered twice a day.This seedling wilts easily until it starts putting roots into new soil.The leaves of pot-bound seedlings will hardly grow for a week to ten days after transplanting.

Why would you spend a lot of money buying seedlings to jump-start the growing season if they aren’t going to grow for a week to ten days after you set them out?

A seedling perfectly ready for transplanting will have extended the tips of many roots right out to the extremities of its container, so its soil ball will hold together during transplanting. This seedling can grow from the first day it is put out.

So take a look! Place the stem of the plant between your second and third fingers, hold your palm against the soil, turn the pot upside down so your hand supports the soil, tap gently on the side of the pot, then lift the pot, exposing the soil, and see if you can see any root tips. If none are visible, the soil will be crumbling into your cupped hand. In that event, carefully repack the potting mix and set the plant back down. Let someone else buy it. If you do buy it, be prepared to keep it alive in that pot for about a week, waiting for the root system to develop enough to withstand the mechanical stresses of transplanting.

How did that unbalanced seedling get that way? Isn’t the root system’s development supposed to match the growth of the top? Yes, it is. But the owner of the greenhouse raising those seedlings was faced with ethical temptations. Profit in that business is determined by how long the seedling will occupy greenhouse space before being taken to the sales bench.The raiser can accelerate top growth — which is what the buyer sees, which is what leads to the sale — by making the greenhouse warmer at night and using a fertilizer balance that pushes top growth at the expense of root development. Or the nursery can sell a variety bred to look good at four weeks old — profitable for the seedling raiser, but not necessarily good for the gardener.

If the seedling is pot-bound, you’ll see it right away.Don’t buy it.How did it get that way? The seller kept it looking good for a week or more after it should have been sold by feeding it fertilized water and watering it several times a day.

Soft seedlings?When plants are grown at high temperatures, particularly at night, they grow lushly — leaves and stems get much larger — but a goodly part of this size is nothing but water stored in swollen, weak-walled cells.When plants don’t experience wind, they are mechanically weak. The gentle battering caused by light breezes actually exercises the plant and causes it to reinforce its connective and structural tissues. But if a seedling diverts its energies into making strong structural tissues, it won’t be as large or lush looking. Many seedling growers crank up the heat (there is no wind inside a hothouse) and then, after four weeks, move these attractive-looking seedlings directly out to the sales bench.

Quote from Stokes’ 2005 catalog listing two similar varieties of Chinese cabbage:

76 MICHILI 78 days. The standard open pollinated tall cylindrical strain used by bedding plant growers ... We recommend hybrids for commercial crops. 1 lb: $7.60

76G Monument 80 days (F1 hybrid). Taller, much later than ... slower to bolt ... l lb, about $70.00 (price approximate because quality hybrids are sold by the 1,000 seeds).

Item 76 will produce a high percentage of off-types and non-heading plants. Item 76G will produce a row of heads as similar as peas in a pod. Stokes is telling us that typical bedding-plant growers are selecting their seeds based on cost, not on the results obtained from growing them to harvest.

Then someone buys this pampered plant and puts it in the soil. On its first night outside it gets chilled, something the seedling never experienced before. This chilling, nowhere near frost but still nippy, is a severe shock that sets the seedling back so hard it can’t grow for a week. The next day is cool and overcast, and the wind gets a bit gusty. The seedling never experienced wind before, so its leaves and stems get badly bruised, if not torn and shredded. Another shock; another setback. Next day the sun comes out full blast. The seedling never experienced unfiltered sunlight before, having always lived under plastic that filtered out about 15 percent of the energy. Another shock. In that strong light, its underdeveloped (or pot-bound) root system can’t bring in enough water and it wilts a bit ... another severe shock.And then some disease or insect that wouldn’t normally harm a healthy plant takes it out. Or perhaps the seedling manages to run the gauntlet of hardening off (adjusting to normal conditions) and finally gets to growing right, but it might take two weeks to get past this hardening off.

You will know it was a soft seedling (if it survives) because it’ll make much smaller leaves a few weeks after transplanting than it had when you purchased it. A properly hardened seedling that looked smaller and more wiry when it was planted out at the same time will be way ahead two weeks later.

Ethical seedling raisers harden off their seedlings by moving them from their mimimally heated greenhouse to what is called a cold house when they are about three or four weeks old, then growing them on in this more natural environment for a few weeks until they have toughened up.A cold house consists of a plastic roof and enough side walls to somewhat break the worst of the wind if it should get to blowing strongly.The structure is designed to raise nighttime temperature a few degrees but still allow the seedlings to get a bit chilled. The seedlings end up smaller, and the stems and leaf stalks look a bit like an endurance athlete in tip-top condition — no fat and with corded muscles showing.

On the sales bench and given the choice, the average buyer will choose the soft, tender, lush seedling over one that has been hardened off properly. And thus the ethical temptation is doubled because hardening off lessens salability and, because it takes another few weeks, it also costs the raiser more.

What’s a gardener to do about all these risks? If you’re buying, make sure you can trust the seller. Grow your own seedlings? My answer: yes and no. Grow your own, yes, but more importantly, be they yours or grown by someone else, don’t transplant plants unless absolutely necessary.And in Chapter 5 I’ll show you that transplants are rarely necessary.

Growing your own seedlings the easyway

I suggest you focus on growing vegetables that can be directly seeded in spring. Yes, transplanting allows you to harvest some chill-hardy crops a few weeks ahead of those you direct-seed, but this takes a lot of work, and if you adjust your attitude a bit, this effort will seem unnecessary, even a bit foolish.Accept my advice for this year, at least, and you won’t need to grow or purchase more than a few dozen seedlings. You won’t need greenhouses, hot frames, heat mats, seedling trays, etc. And your directly seeded vegetables will come up handsomely because you are going to follow my advice (in Chapter 5) about where to buy strong seeds and do what I suggest to make them perform. If you want to push the limits, there is no shortage of books that’ll help you build greenhouses and hot and cold frames; there are nursery suppliers that’ll outfit you with the neatest of seedling-raising gear. But to simply and inexpensively get a lot of good food in every month it is possible to get it, none of these exertions and expenses and stresses are needed.

My advice is to grow seedlings only for those fruit-producing species that benefit from being given every possible frost-free day: i.e., tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants. If you garden in a short-season area, you may want to start a couple of melon or winter squash transplants.Here’s how to do it yourself.

Soil for raising seedlings

Do not purchase potting mix. It is often not soil but decomposed bark and other woody wastes with some chemical fertilizer added. Shade-tolerant indoor ornamentals (plants adapted to growing on the floor of a tropical forest) will thrive in this kind of humus-based medium, but vegetables,which are sun-loving plants, grow in soil. Buying a soil mix correctly compounded for raising seedlings, and made fertile with rich compost, is also a waste of your money. Your seedlings may as well start out in and get used to the same soil they are going to grow to maturity in.

You should have no need for sterilized soil. True, by using a growing medium free of bacteria and fungi you can sometimes coax old,weak seeds into life. But you are going to use strong, vigorous seeds that don’t need coaxing. In a sterile environment, most of the seedlings that come up will thrive. This is profitable in commercial applications. But you are going to plant several seeds for every plant you’ll ultimately grow, so a few losses due to soil diseases won’t matter. In fact, a few losses will be to your benefit because the soil pathogens will eliminate the weaker seedlings for you. The ones that thrive in your own garden soil from the beginning will likely continue to thrive to the end.

To make seedling soil, get a five-gallon (20-liter) plastic bucket and half fill it with ordinary garden soil. If it isn’t clayey soil, blend in about 1¼ gallons (five liters) of well-rotted manure or well-ripened compost. If your garden is new and you haven’t made any compost yet, buy a sack of compost. Beware of using bagged feedlot-steer manure for this purpose; sometimes it contains ordinary salt. If real compost is not available, use sphagnum moss.

If your garden soil is clayey, you’ll definitely require sphagnum moss. If you try to lighten clay up with manure or compost, you’ll probably make the mix too rich to grow good seedlings. Instead, thoroughly mix into clay an equal volume of well-crumbled moss. One small bale should be enough moss to last you through a great many years of seedling raising. I suggest moss because it contains almost no plant nutrients and doesn’t decompose rapidly. It will make an airy mix that’ll stay loose for several months.

So far, what we have done is create an airy, loose growing medium. But unless you made it with super-good compost, the mix will lack mineral nutrients. The best way to fortify that mix is to add exactly one cup (250 milliliters) of complete organic fertilizer (see Chapter 2) to each three to four gallons (12 to 16 liters) of seedling mix. If you have no COF, it is essential you boost the medium’s calcium content, so add a quarter cup (60 milliliters) of agricultural lime.Measure accurately. Blend it in.You should end up with a five-gallon (20-liter) bucket about three-quarters full of fertile seedling mix, enough to fill two or three dozen substantial pots.

Pots

Improvise.Waxed paper or plastic milk containers with a few drainage holes poked into the bottom make acceptable seedling pots. It’s best to use the lower third of the one-quart (one-liter) size. The bottom four inches (ten centimeters) of large-sized waxed paper or Styrofoam beverage cups are good.Or use leftover plastic pots from earlier years when you were foolish enough to buy seedlings.Whatever you use, the seedling pot should hold a bit more than a half pint (250 milliliters) of soil. For starting the fast-growing cucurbit family, which have delicate roots easily damaged by transplanting and which are best grown indoors for no more than one week, make a pot using a three-inch-wide (8-centimeter) strip of newspaper rolled into a squat cylinder, filled with soil, and held together with a rubber band and/or a piece of string. Once filled, the pot must rest on a cookie sheet or something similar until the seedling’s roots have filled the soil, allowing you to pick it up without the earth falling out the bottom. This sort of “pot” is especially useful because the whole thing can be planted without damaging the roots in the slightest. In my own cool-summer climate I use pots like these for starting melons.

Figure 4.1: A seedling pot made with a strip of newspaper and a rubber band or string.

Sowing and sprouting

The soil should be at the perfect moisture content for germination before you sow the seeds because you should not add any water until germination is done. This happens to be the same moisture content you’d want soil to be at before you started digging it.Use the ready-to-till test described in Chapter 3. If the soil is too wet, you’ll end up with considerably poorer germination.

Fill each pot to the top with loose soil and then press down gently with your palm so there aren’t any big air spaces. The soil should end up about a quarter to a half inch (6 to 12 millimeters) below the rim.With the eraser end of a pencil make one small round hole, three eighths of an inch (nine millimeters) deep, in the soil at the center of the pot. Count out four or five seeds and drop them into the bottom of the hole. Press them gently down into the bottom of the hole with that same pencil, but don’t deepen it. Flick a bit of loose soil into the hole to cover the seeds; this way there is nothing weighty to oppose the emergence of the shoots. Now slip a small, lightweight, thin, clear plastic bag over that pot. The bag should be large enough that it can be twisted closed, though I always put the extra plastic under the pot and hold it shut with the weight of the pot on top of it.Why do you use a baggie? Because each time you water a sprouting seed, the medium gets too wet and the moisture makes the temperature drop. Neither of these is helpful. Inside a nearly airtight bag there is almost no moisture lost. The soil starts out at the perfect moisture level and stays that way until the seedlings emerge.

Start solanum seeds (tomato, pepper, eggplant) about six weeks before you’ll want to transplant. Sow the tomatoes first. When these are up and growing, start pepper and eggplant seeds.When these are up and growing in your sunny window, consider starting the hardiest cucurbits: first the zucchini and squash. A few weeks later, after outdoor conditions have become warm and settled enough to put out the tomatoes, think about starting cucumbers and melons. Cucurbits take less than two weeks from the first sowing of seeds to the move out into the garden. This schedule works nicely with one small, heated, germination cabinet.

The germination cabinet

This priceless tool is merely a container roughly the size of a cardboard apple box from the supermarket, whose temperature can be held warm and stable. Unless there is a place in your house where the temperature in springtime is always over 75°F (24°C), all day, and all night, then for predictable results make a germ box. Don’t be daunted. A germ box is the easiest thing imaginable to make or improvise.And once you’ve got one you’ll use it for a few other things that’ll make your gardening a lot more reliable. (It can also be a good place to raise a loaf of bread.)

Few gardeners will want to start more than a dozen plants at one time.A batch of seedling pots won’t be in the germ box for more than one week, so during the spring it can be used to start several batches in sequence.

For many years the oven in our kitchen stove was my germ cabinet because it is a well-insulated box with a 25-watt bulb installed.With the light on, the oven temperature stays about 75°F. After my wife, Muriel, repeatedly objected to this use of her stove in her kitchen, I began to use a germ box made of scrap wood with a small lightbulb on the bottom. It has a sliding glass top (cut from a scrap of double-strength window glass, it sits in grooves or tracks) so that by a combination of changing lightbulbs from 25 to 40 watts and/or opening the top a few inches, I can control the temperature inside to suit. A cardboard apple case would also do well.

You will need to calibrate your box — in other words, figure out how to get it to hold at 75°F to 80°F (24°C to 27°C) by either changing bulb size or adjusting the air flow. Beware: Temperatures exceeding 80°F may lessen germination. Also beware of the fire risk in a cardboard box when you use bulbs larger than 25 watts.

Procedure

The sealed pots can rest on an old cookie sheet or on a rack. For more uniform heat distribution, they are best supported above the lightbulb rather than below it. Three days after sowing, begin checking each pot twice a day. As soon as some of the seedlings have emerged in any pot, remove that one from the germ cabinet, remove the nearly airtight plastic bag, put the pot on a growing tray or shelf in your brightest, most sunny window, and begin watering it as needed. Strong vigorous tomato, pepper, eggplant, and cucurbit seeds should appear within four days; any seeds that take an entire week to emerge will be spindly and lacking vigor and will have difficulty getting going.

When the seedlings have fully opened their first pair of leaves (cotly-dons), use a small pair of scissors or your fingernails to cut off all but the best three seedlings per pot.When the seedlings have developed two true leaves, thin the pot down to two seedlings.When the seedlings have three true leaves, cut off one, leaving one to grow.

When you have thinned down to one seedling per pot, put that seedling outside in full sun during the day when the weather is pleasant. If possible, for the last week before transplanting, keep it outside overnight except when it’ll be shockingly cold or when frost threatens.

Fertilizer

Raising transplants is an occasion to use liquid fertilizer. If you make the potting soil rich enough to push the seedling as fast as possible, the high level of soil nutrients will also encourage soil diseases that attack emerging seedlings. From the time you sow until about the time the first true leaf forms, it is best if the seedling mix provides only minimal NPK (remember: nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium) but supplies plenty of calcium because this essential nutrient can’t be added conveniently in a liquid fertilizer.When the seedlings have developed enough strength that they can resist fungal diseases (for most vegetables, this is when they have developed one true leaf ) it is time to start pushing them. For this purpose, add fertilizer to their water.

Organic liquid fertilizers. Organic gardeners, I apologize; the most effective liquid fertilizers are not organic. That is because it is nearly impossible to get organic sources of phosphorus to go into solution. Liquid fish emulsion and liquid seaweed preparations are deficient in phosphorus. But seedlings need a lot of P if they are to become stocky and strong. If you find a liquid concentrate that says it is organic and also provides a high level of phosphorus, it is almost certain the maker has fortified some fish emulsion with phosphoric acid. Now, phosphoric acid is a most effective fertilizer; it just doesn’t meet the definition of “organic” as prescribed by the certification authorities.

Small batches of seedlings can easily be raised in a sunny window, sitting on a table or shelf. If the light is not bright enough, if the seedlings incline strongly toward the light, or if their stalks seem too thin and spindly, there is a simple and almost costless method to significantly increase the light level. Make a reflector of a large piece of cardboard perhaps 14 inches (35 centimeters) tall and somewhat longer than the line of pots. Cover one side of it with aluminum foil (glue it on or wrap it around to the back and tape it down) or paint it bright white and then prop up that reflector immediately behind the seedlings.

If the seedlings still seem a bit leggy and weak-stemmed, they need exercise. Get a small window fan and make the airflow shake them gently, or open the window a bit. A few hours of gentle breezes every day will cause seedlings to increase the size and mechanical rigidity of their stems.

The best purchasable genuinely organic compromise is an equal mixture of fish emulsion and liquid seaweed.The fish is high in nitrogen; the seaweed has potassium, trace minerals, and assorted hormones that act like vitamins for a seedling. In combination they grow a reasonably healthy, reasonably stocky plant. Another thing that acts as pretty good fertilizer is strong cold brewed black coffee. Even better than the brew is the grounds. Used coffee grounds are a seedmeal that hot water has been passed through. Judging by how coffee makes plants leap forward, I would reckon the grounds to be about half as strong as chicken manure. At times I’ve arranged to take away all the coffee grounds from a nearby restaurant that has a busy espresso machine. I spread them and dig them into any area of my garden that is being prepared for planting. They could also be put into a compost heap in place of animal manure.

Chemical liquid fertilizers.Any brands sold commonly in garden centers and supermarkets that are about 20-20-20 and also list trace minerals on the label work quite well.The best and most costly chemical fertilizers are hydro-ponic nutrient solution concentrates. Hydroponic fertilizers formulated to produce vegetative growth should also supply reasonable amounts of calcium, a difficult chemical feat.

Amount of fertilizer. Potting soil made with COF, as I suggested, grows healthy plants, but grows them slowly.When you try to speed results, there is a far greater risk from overfertilizing, which poisons the seedling, than from using too little. Even slight fertilizer toxicity will prevent seedlings from growing as well.This is particularly dangerous because the typical response to poor growth is to think the plant needs even more fertilizer. Take no chances! Mix liquid fertilizer, be it organic or chemical, at one third the recommended strength and then use it at that dilution about every other time you water. Seedlings mainly need fertilizer when the sun shines on them and makes them grow, so during cloudy spells, when plants don’t grow much, you naturally don’t water them much. When the sun is shining and you’re watering more frequently, the plants will automatically get the increased fertility they need to grow.

Transplanting tips

By paying attention to the following tips, you can reduce transplanting shock and see your seedlings get off and growing quickly.After all, isn’t that why you went to all the trouble of raising seedlings  in order to harvest them as soon as possible?

in order to harvest them as soon as possible?

Set each seedling into a super-fertile hill. After preparing the bed or row, remove one big shovelful of soil from each spot a transplant will go. Set the soil beside the small hole you’ve made. Into the bottom of that hole toss half a cup (125 milliliters) of COF or about a pint (500 milliliters) of strong compost. By digging, blend the COF or compost into about a gallon (four liters) of soil so that most of this amendment will be located below the seedling.

Now slide the loose earth you removed at first back into the hole. Smooth out the spot and scoop a small hole in the center with your hand. The hole should be about twice the volume of your seedling’s rootball and deep enough that when the seedling is put in and the hole refilled, the soil line will fall just below the seedling’s first two leaves.

Unpot the seedling and gently place the rootball into the hole, minimizing damage to the roots and avoiding breaking off any soil from the rootball.

Mix a bucketful of full-strength liquid fertilizer or use compost/manure tea. Take a quart jar or tin can, scoop out a quart (liter) of fertigation (see Chapter 6), and pour it into the hole, gently enough to not wash soil away from the rootball but rapidly enough to fill the hole before it soaks in. Then quickly push loose soil back in around the seedling’s rootball, creating a muddy slurry that will settle into all the nooks and crannies of the rootball, causing a tight connection to form between the roots and the surrounding soil. If you do this step right, the seedling will not need watering any more often than anything else in the garden from then on. It’ll grow really fast, too.

Reasons not to use transplants

For gardeners operating in a short-season area, setting out transplants is the only way to get more than a few ripe tomatoes before the summer is over. Even if you enjoy a long frost-free season, getting your first ripe tomato six to eight weeks early is a worthy ambition.The same is true for peppers and eggplants. So raising seedlings for these species and transplanting them out as early as possible is not a bad idea.

But when it comes to other vegetables, using seedlings doesn’t make as much sense.

You don’t save all that much growing time.No matter how skillfully you set out the transplant, no matter how well hardened-off the seedling is, transplanting almost always sets back growth. A five-week-old seedling set out at the same time that seeds are sown will usually come to harvest only about three weeks ahead.And you can often get spring crops to germinate earlier, in colder and less-hospitable soil than you might think they could, simply by “chitting” them before sowing. (Chitting will be fully explained in Chapter 5.) So instead of feeling urgency in spring, relax.Accept that directly seeded crops will start yielding a few weeks later than they might had you used seedlings.

Suppose you want a continuous supply of small cabbages, two each week. Suppose, where you garden, the earliest that cabbage seeds can sprout outside is three weeks after the spring equinox. On that date you sow four clumps of cabbage seeds directly in their growing positions, enough to supply the kitchen for two weeks.At the same time you transplant six tough, well-hardened-off seedlings that won’t go into shock when hit with a light frost. Even though these will be set back a bit when you put them out, they’ll still mature a month ahead of the direct-seeded cabbages. To maintain a steady, continuous supply, directly seed four more plants every two weeks from that time onward.

Consider a slow-growing crop like celery. Raising seedlings to transplanting size takes not five weeks, but ten. Two and a half months of tending little plants in trays seems a bit much to me. Instead, I sow celery (and celeriac) directly in place, but in my mild winter maritime climate I do it rather late in spring so these tiny seeds have time to germinate before hot weather comes. Where winters mean freezing soil, directly seed celery in mid-spring for late-summer and autumn harvest.What’s wrong with that? There’ll be plenty of other things to eat during high summer.Where winter is entirely mild, you can direct-seed celery after the heat of summer has passed and it becomes a cool-season or winter crop.Whatever you have to do to insure that celery seed germinates, it will end up less trouble than tending seedlings for ten weeks and then transplanting them.

Direct seeding produces a stronger root system. Many vegetable species make a taproot. But when the young plant is confined to a small pot, the taproot disappears. The transplanted seedling then forms a shallow root system lacking subsoil penetration. This makes little difference as long as you have plenty of irrigation. But should you try to grow a garden on rainfall or in less than ideally fertile soil, the vegetables’ ability to forage in the subsoil is critical.

Don’t be a slave to your garden. Growing transplants takes a lot of close attention. They have to be watered every day that it isn’t raining, and sometimes, if you use small containers so as to get a great many of them going in a small space, you have to water twice a day.Neglect them just once, go off on a visit and forget to come home in time one sunny afternoon, and the whole effort of weeks might be lost in one mass wilting. Seeds sown in the same place they’ll grow to maturity are far more capable of taking care of themselves.

If you’re taking my advice and avoiding garden center transplants, you may turn instead to the rack of seed packets on the other side of the store. But now I’ll tell you why you shouldn’t buy most of those either.

When I began gardening in the 1970s, seedrack picture packets were low-quality stuff. I found a broader assortment of varieties by mail order, but most of it proved to be the same low quality. There were also a few ethical mail-order seed companies.There still are, but 30 years later the overall situation is even worse.

WalMartization has further degraded the picture-packet rack. Independent garden centers, unable to compete, are vanishing. Transnational retail chains use enormous buying clout to squeeze seedrack jobbers’ profits. In consequence, in the same way there have come to be fewer retailers, there now are fewer large seedrack picture-packet companies, and the survivors are struggling ever harder to turn an ever-dwindling profit. So, in turn, the desperate seedrack companies have no choice but to demand even lower prices from their already low-priced suppliers, companies specializing in growing cheap garden seed for seedrack and mail-order retailers.These suppliers, the actual producers of seed, are termed “primary growers.”

In my first business I learned that every product or service could be compared to a three-legged stool, with the legs being price, quality, and service. If you lowered one leg, you had to lower the others accordingly or the stool tilted.Cut price, and the quality and service have to go down similarly.Ask for an increase in quality or service and you have to be prepared to pay more. So the primary growers of cheap garden seed, faced with an implacable demand for even lower prices, cut quality. They had no choice.

How do you cut quality on something that is already low quality? You’re about to learn a few things about how the garden-seed business really works.

Sweepings off the seedroom floor

The year I put out my first mail-order catalog, I visited the nearby regional facilities of a primary seed grower.This company produced most of the traditional well-known open-pollinated varieties used in the garden-seed trade. Its garden-seed prices were extraordinarily low. If I wanted to offer the traditional varieties familiar to most gardeners, I could find no other source to buy them from.

The district manager was pleased to meet this newbie to the trade, share a cuppa, and see what he could do to more firmly cement a relationship. In a fatherly way he set out to educate me.He explained that I should continue to buy most of my seed from his company because it supplied most of the seed used by most of the mail-order catalog companies and picture-packet seedrack jobbers in the United States and Canada. Because it did such high volume, it grew new seeds for most of the varieties every year. Thus I would not be getting old seed from him, no weak stuff that had been sitting around the warehouse for years before it became “new to me.”

Then he informed me that to please the home gardener, the most important thing was that the seeds I sold came up. If after that the seeds did not grow too uniformly and did not produce the highest-quality vegetables, it did not matter.Of course, he said, at its low, low prices, his company’s garden seed could not be of commercial quality. “But,” he said, “the gardener is not a critical trade. You can sell the gardener the sweepings off the seedroom floor.”

Sweepings? When seed is harvested it is mixed with chaff, soil, dead insects, weed seeds, and other bits of plant material, so it passes through machinery that shakes and blows and sifts and separates in all sorts of clever ways. The good fat dense seed goes into the bag; the chaff, soil, small seed, weak seed, light seed, and immature seed tends to fall to the floor.This is the “sweepings.” In this case the term was a metaphor; he was referring to other aspects of quality.

Critical trade? The farmer or market gardener is a critical trade. Suppose the crop is cabbage. If it seems to grow okay but a large percentage of the plants fail to head properly, farmers know they’ve been defrauded.There may be a lawsuit because they will have lost a huge sum. Farmers know how many days it takes for a familiar type of vegetable seed to come up. If broccoli seed usually emerges in four to six days, but the lot just planted took eight days to show and the weather wasn’t cold during those days and the emerging rows are spotty, the seedlings look spindly, and many of them proceed to die before they get established, farmers have no doubt that the seed was weak. At very least they are going to be looking for another seed supplier and will grizzle about Company X at the coffee shop. But let that same thing happen to gardeners, let seed germinate badly or fail to yield uniformly and productively, and inexperienced gardeners, not being a critical trade, wonder if it was their watering, their soil preparation, the depth they sowed at, or any of a handful of factors they are uncertain about. Almost never does the home gardener blame the seed. Besides, the gardeners are out only a few dollars for a small packet,where farmers might have invested a few hundred dollars per acre for a field of 80 acres. And probably each of those 80 acres consumed a few hundred dollars’ worth of tractor work.When farmers take a $16,000 loss on seed, they don’t just shrug.

What could make a worse loss than a poor germination? Suppose the seed came up vigorously and grew rapidly, but at maturity yielded something surprising, something unmarketable. In that case the unfortunate farmers would have spent additional hundreds of dollars per acre on pesticides, cultivation, etc.Not to mention what lawyers call “lost opportunity.”Yes, those farmers wouldn’t just shrug.

Ah, ha! said I, the novice seedsman, to myself.Too bad I’m committed to buy from this guy for this season. Before I order any more seed for next year, I am going to find high-quality suppliers! And it also became clear to me at that instant that the only way to be sure of what I’d be selling would be to put a lot of effort into my variety trials.

Commercial quality seed

Two factors make seed suitable for market gardening and farming — and highly desirable for home gardening, too: genetic uniformity and vigor.

Genetic uniformity.When you sow seeds for iceberg lettuce, you want a row that makes heads that will hold for a week or more without becoming bitter. But suppose a large percentage of those plants emit bitter seedstalks before the head is ready to be cut. If you’re growing broccoli you want to cut flavorsome, small-beaded, central flowers without a lot of small leaves coming out of them, not a loose flower with enormous (coarse), harsh-flavored beads that are already turning yellow and preparing to open before the flower has reached half its final size.

Most varieties are prone to deviation, especially so in species whose pollination is done by insects or wind.What stands between the variety’s ongoing usefulness and its deterioration is the plant breeder,who spots chance mutations and unintended crosses with other varieties in the seed production field and gets rid of them. Every seed production field must be patrolled regularly, with each and every seedmaking plant studied carefully to make sure that any off-types are removed. If the species is insect- or wind-pollinated, someone must also patrol the surrounding area to make sure that no flowering member of the same species is growing in some neglected field or someone’s home garden.To maintain a quality variety takes a lot of skilled work.That seed has to be sold at a rather high price.

It is easy to produce cheap seed.You simply do not bother eradicating off-types, do not have a highly paid plant breeder doing magical tricks to purify lines, do not rigorously patrol the fields and gardens surrounding production areas, do not carefully hand-select the plants that are allowed to make seed. You plant the seed production field, let it grow unsupervised, harvest the seed, and the next time you are about to grow that variety, you dip into the bag you grew the last time and use it to plant the next year’s production field.When done this easy way, each successive generation becomes ever more variable and ever less productive.

If the variety gets too degraded, the bargain-price primary grower may buy a few pounds of expensive commercial-quality seed of a different but similar-looking variety from a quality seed company and use that to start the next seed production field, whose harvest will be (mis)labeled with a well-known heirloom name.This is why a lot of the “heirlooms” produced by low-price primary growers have nothing in common with the original variety for which they were named.

What I have been describing was standard practice in the cheap end of the home-garden seed trade long before I went into it. But when seedrack jobbers demand even lower prices, the primary garden-seed grower can no longer afford to start out with decent seed.

Vigor.Newly harvested seed usually starts out germinating strongly.Over time, every lot will eventually become so weak that the few sprouts still able to emerge from their seed coats in a sterile germ lab could not possibly establish themselves under real conditions — in the field. Some species have a short storage life. Parsnip seed, for example, rarely sprouts effectively in the third year from date of harvest. The cabbage and beet families routinely sprout acceptably for seven years.

Savvy market gardeners and farmers require a minimum level of laboratory germination for each vegetable species. Should germination fall below that figure, it means the seed is almost certainly too weak to depend on. Farmers and market gardeners find out what the germination of a seed seller’s lot is before they agree to accept it. Territorial Seed Company wouldn’t buy cabbage seed unless it was 85 percent germ or better.When I was offered a lot exceeding 90 percent I would smile because it was a virtual certainty that it would sprout strongly. If I had to carry over unsold seed from that lot, it would certainly sprout well the next year, too, and would likely sprout well enough to sell proudly two years later.

Because germination ability is a major question when buying seeds, and can become a thorny legal issue between buyer and seller, there is a body of seed law.The rules of Canada, the United States, and the European Union are quite similar. In the US, for example, any time a package of seed weighing more than one pound (454 grams) is sold, it must show the results of a germination test done at a certified laboratory within the previous six months.

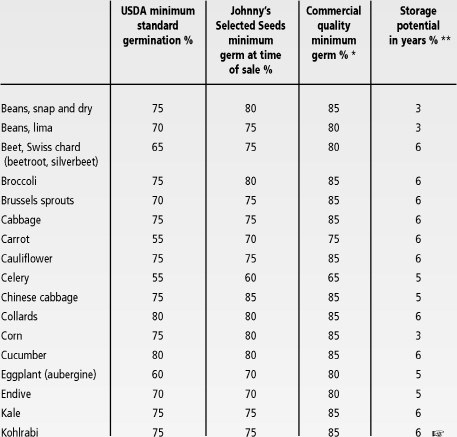

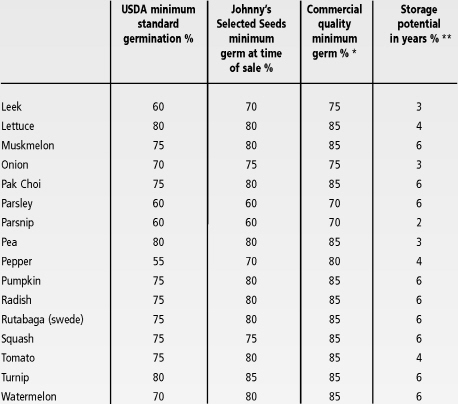

If home-garden seed packets had to be labeled this way, it would make them cost a few cents more per packet. Mainly to create an illusion that the small user of seeds is protected without having the germination stamped on every packet, a regulation termed “USDA Minimum Standard Germination” (or “Canada Number 1 rules” or “EU Minimums”) was established. This regulation includes a long list of minimum germination levels for each vegetable species (see Figure 4.2). If the seed sprouts below that figure, it may not be sold unless the packet is plainly marked “BELOW STANDARD GERMINATION.” But if the seed is at or above minimum germ, nothing need be said; it is assumed the seed is okay.

I said “illusion” in the previous paragraph because the minimums were created by the seed industry for its own benefit. They are so low that no critical buyer would ever knowingly purchase seed that was anywhere near the minimum germination levels.

During the 1980s, Johnny’s Selected Seeds (an admirable American mail-order seed company) included in its catalog a chart showing the first two columns in Figure 4.2. Rob Johnston, the company’s owner, would not knowingly sell seeds that were unlikely to come up and grow in the field, even though it was legal to do so. Please think about what Rob had to go through when buying seeds himself.He would have to bring seeds into his warehouse at germination levels significantly higher than his sell-at minimum. That was the only way to insure they would still be above his minimums six to nine months later, when the user put them into the earth.When I ran Territorial Seeds I tried hard to buy seeds at levels at least 5 percent above Johnny’s minimum levels.

Germination standards

* These figures are my personal best guess of what a knowledgeable and skillful market gardener or farmer would wish for. ** This data pertains to Chapter 5. It is included here to save space.

Figure 4.2

When a seed seller wishes to cut costs, one way is to make no effort to have its packets exceed minimum standard germination. That policy will not mean that all the packets on the rack will germinate poorly. It does, however, mean that not all of the packets will germinate well.And if the company wishes to be dishonest as well as unethical, then it may make no effort to insure its seeds are above minimum standard germ, and hope their state Department of

Agriculture seed cop doesn’t spot this and slap its wrist with a minuscule fine — which is all that happens.

Is it any wonder that people who buy picture-packet seeds come to believe that they can’t reliably make seeds come up and choose to use transplants?

Regionality

When a seedrack jobber operates across the continent and seeks to cut costs in every possible way, one of the things that tends to go by the boards is any attempt to offer regionally appropriate varieties. The compromise is to try to come up with an assortment that appears to work everywhere.This cannot be done, as I will explain in the next chapter.