I have just trashed a large percentage of garden centers. Some sell transplants whose use frequently leads to less-than-ideal results.Most sell seedrack picture packets that offer less than ideal germination, and more than a few of these packets contain poorly selected, nonproductive varieties or varieties not at all adapted to the climate. However, there still remain some independent garden centers run by people who know what transplant quality is, who sell seedlings meeting a high standard, and who offer better-quality seed assortments from mail-order companies that also produce a few seedracks.

If your food gardening is little more than a backyard hobby, an amusement, an entertainment that leads to a random mix of positive outcomes and disappointments, then getting great seeds and seedlings is of little consequence. But for me, gardening has never been a minor affair. It is life itself. It is independence. It is health for my family.And for people going through hard times, a thriving veggie garden can be the difference between painful poverty and a much more pleasant existence.

Starting the garden with quality seeds is essential because of what I call “windows of opportunity,” those brief periods when each crop may be started. The gardener tosses some seeds or seedlings through that window of opportunity and hopes they take root and grow. Then the window closes. For some vegetables there are repeated chances to start a crop. For others the window may only be open for a few weeks.Miss it and there will be no crop that year.

The seeds tossed through that window can take a week to ten days to emerge.There may be but one chance to resow if you immediately realize that the first sowing has failed.The worst disappointment occurs when poor seeds do germinate and seem to grow adequately, but yield little or nothing. The next worst happens when the seeds germinate a bit slowly and a bit thinly and then proceed to grow poorly due to lack of vigor. In this case, gardeners rarely realize what is happening in time to resow. Gardeners who depend on their gardens know they can’t take chances; they grow their own seedlings and source quality seeds by mail.

The word “ethics” means doing what would probably result in the greatest good for the greatest number of people. The opposite of ethics is criminality, which is about getting something for yourself without giving back anything in exchange. Many individuals are in business primarily for profit, for self. This low level of ethics produces little concern for other people, who are supposed to look after themselves in every transaction.This is the source of the old expression “Let the buyer beware.”Other individuals take great joy in doing business primarily to provide a service to others, and secondarily to make a living.

Being ethical does not mean your responsibility is discharged merely by following the letter of the law. It means that your business does what is necessary to provide the service it was set up to accomplish.

If you were to ask the owners of an ethical vegetable-garden seed business what the goal and purpose of their business was, the response would be something like: “Our company exists to help independent people who grow their own food become more self-sufficient, healthier, and more economically secure. To do that, our business —

• provides seeds that have a high likelihood of germinating,

• provides varieties that are adapted to thrive in the buyer’s climate,

• provides varieties that are suitable to a self-sufficient homestead lifestyle (instead of selling varieties that suit the needs of industrial agriculture), and

• honestly and accurately describes the performance and qualities of the varieties sold.”

Of course there are additional (and entirely ethical) reasons to sell vegetable seeds. Some companies specialize in gourmet or unusual vegetables. This is a backyard hobby market in which the customer’s main concern is not reliability or production. It could be perfectly okay to sell this sort of customer rare seeds that don’t germinate terrifically well. It could also be okay to sell a gourmet variety that is irregular, with many individual plants proving to be nonproductive. Another sort of seed company specializes in heirlooms.Often its seeds are organically grown and produced by a network of collaborating amateurs. Because it is amateurs doing the production, their varieties often become irregular, inbred, weak. Because the enthusiast often has little idea of the correct way to handle and store seed, the germination levels tend to be sub-par.Not always, but frequently. Coping with these uncertainties doesn’t matter to someone with a passion for knowing and growing antiques, but degraded heirloom varieties might not suit someone who wants to efficiently grow nutritious, chemical-free food.

To insure it is selling the types of seeds and varieties it wants, the owners of an ethical seed company will take the following steps to fulfill the four points listed above.

Germination

In the discussion of Figure 4.2 in Chapter 4, I mentioned that Johnny’s Selected Seeds included information on the minimum germination level of the seeds it sold.Other mail-order seed companies also have in-house minimum germination levels significantly higher than the standard set out in the seed law and, as commercial suppliers do, perform germination tests twice a year on all lots of seed in their warehouses. This sort of company either has a large market gardener and farmer trade as well as home-garden customers and sells the same seedlots to both, and/or the company wishes to act with the highest possible level of responsibility.

It must seem easy to be slack, unethical; so many are. But it is not easy to send thousands of dollars of weak seed to the garbage every year. If you’re only supplying the home gardener it can be tempting to sell weak stuff anyway.

After all, the gardener is not a critical trade ...

Variety trials

To honestly describe its varieties, the seed company must actually grow trials. This is also the only responsible way to choose which varieties to sell. There is nothing particularly difficult about conducting trials; it just takes a bit of land, focused effort, and a fair bit of money. I reckon the minimum size for a meaningful trials ground would be about half an acre (2,000 square meters) for a small homestead seed business. A medium-sized mail-order company might use a few acres. I know of three large mail-order businesses using about ten acres (four hectares).

Trials are usually laid out in widely spaced rows so that each plant can be evaluated. Enough plants of each variety are grown to determine if the variety is uniform — to see if all the plants are equally productive. If it is a cut-once or yank-out vegetable like cabbage or heading lettuce or carrots, this question needs to be answered: Will the plants all mature at once or is the harvest period spread out? The commercial grower wants uniform maturity.The family kitchen usually prefers the harvest to be spread over a long period unless it intends to can or freeze the harvest. A worthwhile trial needs at least five or six plants for something like a cabbage or cauliflower variety, and a minimum of a ten-foot (three-meter) row for something like a carrot or beet variety. Thus, to do a cabbage trial, one might grow five plants each of 20 varieties being inspected, or a total of 100 cabbage plants. A trial like this can show which varieties are well suited to the home garden, how long they take to head up, how big they are, how long they hold before bursting, how much frost they’ll tolerate, if they’re tender enough for good slaw or tough enough for good kraut, etc.

Is there any other way to determine a catalog offering? Sure, but it would not be as ethical. A company can assume that commonly known varieties must grow well, or it could ask the local agricultural extension office what suits the area and sell that. A seedsperson could ask suppliers which varieties are good for the home gardener and then accept what is offered. But for real, believable, and accurate information, you have to do trials.

Only your own variety trial can reveal what tastes good. Reading between the lines of research-station trial reports won’t help you find that.The main test I use in my own trials is to taste everything raw in the field. If a variety doesn’t pass that test, it rarely progresses to an evaluation of its taste when cooked.

If the trials-ground master doesn’t like raw veggies, he or she will probably rate things differently.And that’s what makes a horse race. But whether raw fooder or cooked fooder, I don’t believe it’s possible to have effective home-garden trials conducted by someone who is not a serious vegetableatarian. Otherwise, the varieties are being evaluated in much the same way that commercial varieties are ranked — by appearance, storage potential, ease of harvesting, etc. Not that these factors are unimportant. But for the home gardener they are secondary to flavor, culinary qualities, storage potential in a root cellar, etc.

Organically grown trials can show which varieties resist diseases or insects. I repeat, if they are done organically.

“Grow outs,” taking a look at how the seeds purchased for resale actually grow, also happen on a trials ground. Except for a few mail-order businesses dealing in heirlooms, retail garden-seed suppliers are mainly distributors. They buy bulk seed and repackage it. There is no commodity more open to misrepresentation than vegetable seeds. A bag of cabbage seed can correctly cost $10 a pound wholesale or $250 a pound wholesale.The contents of both bags look identical — small round black seeds. The bag is labeled with a germination percentage determined within the previous six months.This can be easily and inexpensively checked by the buyer within one week of receiving the seeds, simply by counting out 100 seeds and sprouting them. But what those seeds will actually produce is another matter. Cabbage seed that costs $10/ pound does not produce a row of identical heads.Many of the plants may not form a proper head at all. Cabbage seed that costs $250 per pound should yield a row in which every plant heads up perfectly and identically.

From time to time a primary grower has been known to “accidentally” mislabel a bag intended for the home-garden trade, sometimes enclosing suspect seed from a discontinued variety worth next to nothing in place of its finest item. (This never seems to happen to the grower’s commercial customers.) On one occasion the bag I bought labeled “kale seed” turned out to contain some sort of fodder plant that was virtually inedible by humans. The only way to purge these items from one’s inventory is to grow a small sample of all the seed lots purchased. At least this way the incorrect seed will not be sold for more than one season. The wronged seed merchants can then complain and demand a refund, keep their suppliers on their toes, and reduce the likelihood of being the recipient of such “mistakes” in the future.

If the retailer grows out everything in its catalog for which a new lot of seed was purchased that year, that would make a pretty large garden in itself. And doing it costs a pretty penny.

Adapted to the region

It would be profitable if one catalog could sell fine vegetable varieties that would grow anywhere. But that is not possible.To ethically sell across the whole English-speaking world, a company would have to operate a different trials ground in each broad climatic zone being served. Instead, mail-order suppliers tend to be regional. Unless, of course, they don’t bother growing trials.

When you purchase seeds, you have a far higher likelihood of a successful result if the supplier’s trials grounds are located in roughly the same climatic zone as your garden.Here is a “climate map” drawn in the broadest of verbal brush strokes:

Short-season climates. This area comprises the northern tier of states in the United States and that part of southern Canada within a few hundred miles of the U.S. border (the area of Canada in which over 90 percent of its citizens live).

Moderate climates. The middle American states, the east coast of Australia roughly south of Sydney, and the North Island of New Zealand are moderate climates. In the United States, this is where summer gets hot and steamy (the frost-free growing season is more than 120 days), and the winter is severe enough to actually freeze the soil solid at least 12 inches (30 centimeters) deep. This level of winter cold isn’t felt Down Under except at higher elevations. To roughly delineate this area in North America, draw east/west lines from about the northern border of Pennsylvania and the southern border of North Carolina extending to the Rockies. Lower New York state, the part south of a line from Albany to Buffalo, might also be included. Maybe Connecticut, too.

Warm climates. This includes the southern American states and coastal Australia from Sydney north up to, say, Bundaberg.The soil here never freezes solid; the summers are long and hot. The climate may be humid or arid. The comparatively brief winters can occasionally be frosty but are mild enough to allow for winter gardening without requiring protection under glass or plastic.

Maritime climates. In North America this bioregion is sometimes called Cascadia. It includes the redwoods of northern California, extends into Oregon, Washington, and the Lower Mainland and islands of British Columbia, always west of the Cascade Mountains. England, Ireland, Wales, southern Scotland, southern coastal Victoria, Tasmania, and the South Island of New Zealand have about the same climate. These regions usually have relatively cool summers. Rarely does the soil freeze solid in winter except at higher elevations and where it is isolated from the ocean’s moderating influence.When a period of sub-freezing weather does happen, the earth doesn’t freeze deeply, nor does the freeze last long.Winter gardening ranges from difficult to easy and productive.

In 1989 I wrote an article for Harrowsmith, then a brave country-lifestyle magazine. I explained the garden seed trade and evaluated and ranked mail-order companies.Why do I say “brave”? Because mail-order seed sellers made up a large portion of Harrowsmith’s advertisers, and my article offended more than a few of them. First I sent out 69 questionnaires on Harrowsmith‘s stationery, stating that I was the ex-owner of Territorial Seed Company, that I was writing an article evaluating garden seed companies, and that I might telephone for further information after the questionnaire’s answers had been received. Some of the questions were: Do you have a trials ground? If so, how large is it? Do you have your own in-house germination laboratory, even if uncertified? If so, how often do you test the seed lots on your shelves? What germination standards do you use to decide if a lot is fit to sell? What percentage (or how many) varieties in your catalog are actually grown by your company?

After eliminating those who elected not to respond (about half, which was not a surprise to me), I then removed from consideration those without trials grounds. Out of 69, only 20 were left. After a probing telephone chat with the management of these companies, I found 11 were worth recommending. For this book I have expanded my recommended list to include admirable suppliers in the U.K. and Australia.

The following are the businesses (organized by climatic zone) I’d advise serious food gardeners to use for the essential core of their gardens. They are the companies most likely to supply first-class seeds.When you garden to produce a significant amount of your family’s food, you can’t afford to use poor seed!

Your current seed supplier may not be included in my recommended list. Why am I so critical? Because when I grew proper variety trials for eight years, I saw undeniable and large differences between varieties. I want you to have the best possible chance of realizing a productive and useful outcome. I reckon you can’t afford to experience anything else.

Short-season climates

Stokes Seeds. Stokes, a Canadian company located near Niagara Falls, has a 10-acre (four-hectare) trials ground open to the public, as well as an additional 24 acres (ten hectares) that is not open and is used for research, plant breeding, and seed production. The company’s main income is from farmers and market gardeners, but the home gardeners get the same quality of seed as the commercials. I have never purchased a Stokes packet that failed to come up acceptably. If Stokes’ catalog has any weaknesses, they will be found in its offerings of home-gardener-only vegetable species — items that have no commercial interest such as kohlrabi, kale, winter radishes, celeriac, and other unusual veggies. For these I often find Johnny’s a better source. Stokes makes two identical catalogs: one in US funds; the other in Canadian.

Stokes Seeds, PO Box 548, Buffalo, NY 14240 USA.

Stokes Seeds, PO Box 10, Thorold, ON L2V 5E9 Canada.

Both countries served by 1-800-396-9238 and www.stokeseeds.com

Johnny’s Selected Seeds. In 1973, Rob Johnston, age 22, bootstrapped Johnny’s with $500 in operating capital.The company is currently using about 40 organically certified acres (16 hectares) for trials, research/development, breeding, and seed production. Johnny’s has bred and now grows seed for a significant number of its own varieties. Johnny’s catalog offers many organically grown items and avoids selling fungicide-treated seed. Like Stokes, Johnny’s offers small packets suitable for home gardeners and also sells the same varieties in larger amounts to market growers. Besides a broad line of vegetable seeds, green manures, and cereals, Johnny’s sells a wide choice of organically grown, state-of-Maine-certified seed potatoes, a range of garlic varieties, etc.The company routinely ships to Canadians; non-commercial quantities do not require special certification nor do they incur import costs. But Johnny’s may not send fava beans to Canada (nor corn to B.C.).There are also Canadian import restrictions on living plant materials like seed potatoes and garlic, and on some grains. Canadians venturing beyond vegetable seeds would be wise to telephone or check Johnny’s website before ordering. Johnny’s ships overseas (to me), too.

Johnny’s Selected Seeds, 955 Benton Ave., Winslow, ME 04901 USA; (207) 861-3900; www.johnnyseeds.com

Veseys Seeds. Veseys was started nearly 70 years ago by a market gardener who began importing high-quality European seeds for his neighbors. The company’s varieties all pass the test of reliable short-season maturity in trials on Prince Edward Island, and a rigorous screen it is, too. Seed-germination standards are constantly monitored in the company’s own germination lab.Veseys will ship overseas.

Veseys Seeds, PO Box 9000, Charlottetown, PE C1A 8K6 Canada; 1-800-363-7333; www.veseys.com/

William Dam Seeds. William Dam has just published its 56th annual catalog. The company operates five acres (two hectares) of vegetable (and flower) trials and focuses on high-grade hybrid Dutch imports. I am pleased to see many of my favorite short-season varieties in Dam’s catalog. The catalog also contains some old and highly degraded open-pollinated varieties (OPs) offered for the “organic” trade that I wouldn’t touch: specifically DeCicco and Waltham 29 broccoli, as well as Snowball cauliflower.Dam will ship overseas.

William Dam Seeds, PO Box 8400, Dundas, ON L9H 6M1 Canada; (905) 628-6641; www.damseeds.com/

Moderate climates

Stokes Seeds. Stokes’ location straddles the short-season/middle-states line. For that reason this company’s offering is appropriate for middle-states gardeners. However, the catalog lacks some of those really heat-loving species and varieties considered “southern” vegetables. Contact details above.

Johnny’s Selected Seeds. Generally, varieties that grow well where summer is cool will do even better where it is warmer. Almost everything in Johnny’s catalog should suit until you go far enough south that the summers get really steamy. My doubts about using these seeds south of Pennsylvania/ the Ohio River are unproven, but likely correct. Contact details above.

Harris Seeds. A decade ago, after 100 years of family management, the last of the Harrises sold the business to an international agribusiness company. Not too many years later, some of the original employees bought back the business and it is again in private hands. Harris’s main business is with farmers and market gardeners. Unlike Stokes, which sells its entire line to all customers, Harris has two catalogs and offers a somewhat limited assortment of the same quality of seeds to home gardeners. Because its trials grounds and breeding focus are on a climate much like that in which Stokes operates, the main reason to deal with Harris is to access some of its historic varieties, such as incredibly delicious Sweet Meat squash and the Harris Model parsnip.The catalog is definitely worth a look.

Harris Seeds, PO Box 24966, Rochester, NY 14624 USA; 1-800-514-4441; www.gardeners.harrisseeds.com/

King Seeds. Down Under gardeners will appreciate this broad offering of generally high-quality vegetable seeds from major international seed growers, as well as herbs (and flowers). The catalog is especially valuable for its many lettuce varieties not otherwise found in Australia.The only obvious weakness in the catalog is the low quality offered in a few types of vegetables the company probably considers unimportant, such as kohlrabi and Brussels sprouts.

King Seeds, PO Box 283, Katikati 3063 New Zealand; (07) 549 3409.

King Seeds, PO Box 975, Pentrith, NSW 2751 Australia; (02) 4776 1493. www.kingsseeds.com.nz

Southern Exposure Seed Exchange. SESE is owned and operated by an “egalitarian income-sharing community,” whose main concern is safeguarding and advancing seed production that is not in the hands of global megabusiness. Were I gardening in the middle states of the US. I would use its offerings for, as its name suggests, it provides access to heat-loving, traditional varieties. SESE is hoeing a difficult ideological row as it tries to maintain a quality offering while (1) avoiding seeds that aren’t organically grown, and (2) having at least 40 percent of its varieties produced by a network of relatively inexperienced small growers. Most of these, but not all, are certified organic, but their results are not always reliable.Many SESE varieties are family-preserved heirlooms. In my own garden I am not willing to waste valuable space and effort growing a low-or non-producing variety in an attempt to be on the side of the angels. I would not purchase the following refined types from them because these need the best-possible breeding to be productive: Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, OP broccoli, celeriac, kohlrabi, Florence fennel, bulbing onions (their scallions will be fine), salad radishes, turnips, rutabagas (swedes).They sell top-quality organically grown seed potatoes that are certified virus-free by the state of Maine.

Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, PO Box 460, Mineral, VA 23117 USA; (540) 894 5480; www.southernexposure.com/

Warm climates

Park Seed Company. I smile when I read Park’s catalog.Virtually every variety the company offers represents the finest breeding attainable, entirely appropriate to its almost semi-tropical climate. This regionality is the result of many years of rigorous trials. Park bulbing onions are plainly labeled as medium- or short-day. Park sells doubly certified seed potatoes (Irish), both organically grown and produced from virus-free tissue-culture clones.That means they’ll be maximally productive. There are also seven varieties of sweet-potato shoots. Park’s rigorous germination standards exceed federal minimums. Because of the hot, humid weather in South Carolina, the company’s seed is stored in climate-controlled conditions, and all its small seed is packaged in moisture-proof foils. And Park’s prices are entirely reasonable. It’s as good as it gets. Park will ship to overseas customers and send catalogs to foreigners who request one by post. Its website is not set up to accept orders from outside North America. Those living up the east coast of Australia north from Kangaroo Valley, or on New Zealand’s North Island, should take a look.

Park Seed Company, 1 Parkton Ave., Greenwood, SC 29647 USA; 1-800-213-0076; www.parkseed.com/

Maritime climates

Territorial Seeds. I opened the doors of this business in 1980, lifted it by its bootstraps, and sold it to Tom and Julie Johns at the end of its 1985 season. I have no ownership or other financial interest in TSCo now, so when I give it good marks, there is no conflict of interest.However, I admire Tom and Julie for growing the small business I sold them into a company as big as any in this list except Stokes.

The certified-organic trial and production fields exceed 40 acres (16 hectares), and all descriptions and days to maturity listed in the catalog are as experienced on the trials grounds. The company has a complete germination laboratory and a resident seed analyst. Its in-house standards exceed federal minimums, and the unpacketed seeds are stored in a climate-controlled warehouse (low temperatures and low humidity). TSCo is producing increasing amounts of organically grown seed. Its broad line of seed potatoes is both organically grown and certified disease-free by the state ofMaine.Originally the focus of the company was to serve only Cascadian gardeners, but Territorial now has as many or more customers east of the Cascades as it does in western Oregon and Washington states. Non-Cascadians should be aware that some varieties on its website, eminently suited to winter gardening west of the Cascades, are too slow to mature before winter freezes the garden solid east of the Cascades. Territorial Seed Company, PO Box 127,Cottage Grove, OR 97424 USA; 1-800-626-0866; www.territorial-seed.com/

West Coast Seeds.West Coast was started about 1982 by a Vancouverite, Mary Ballon, as the Canadian branch of Territorial. Now it is independent. Mary runs a large certified-organic trials ground on alluvial soil near Delta, BC, and otherwise runs her business much as Territorial does in the United States, albeit on a smaller scale. Lately, shipping through the biosecurity barriers to American customers has proved too difficult, and West Coast is abandoning its clientele south of the border. It will ship overseas.

West Coast Seed Company, 3925 64th Street, RR1, Delta, BC V4K 3N2 Canada; (604) 952-8820; www.westcoastseeds.com/

Chase. I have no complaints about any of the three fine U.K. seed houses — Thomson & Morgan, Suttons, and Chase — but Chase is my preference. It offers many highly desirable certified-organic varieties grown by two European quality seed houses, Rijk Zwaan and Sainte Marthe. As an indicator of its attitude consider this: Chase is the only company I know of on this planet that still offers reasonably uniform and productive OP Brussels sprout varieties. It is entirely happy to serve overseas customers and sends catalogs anywhere without a quibble. Chase is currently one of my mainstays.

The Organic Gardening Catalogue, Riverdene Business Park, Molesy Road, Hersham, Surrey KT12 4RG England; 01932-253666; www.OrganicCatalog.com/

New Gippsland Seeds is located in southern Victoria, Australia. The location is a bit warm to supply someone on Tasmania, but many of the company’s varieties work acceptably here. Mainlanders as far north as Kangaroo Valley in New South Wales should be most pleased with the entire line.

New Gippsland Seeds, PO Box 1, Silvan, VIC 3795 Australia; (03) 9737 9560; www.newgipps.com.au/

Miscellaneous suppliers and sources worthy of note

Dave’s Garden is a website providing handy access to nearly every source of seed and materials a North American gardener would want.www.davesgarden.com/

Fedco Seeds only sells from its extensive catalog (downloadable from its website) and only during the spring. These folks run an honest business. PO Box 520,Waterville, ME 04903 USA; (207) 873-7333; www.fedcoseeds.com/ index.htm/

Green Harvest Organic Garden Supplies provides Australians with a broad assortment of natural pest-management materials, as well as seeds, books, tools, etc. 52/65 Kilkoy Lane, via Manley, Qld 4552 Australia; (07) 5494 4676; www.greenharvest.com.au/

Landreth, the oldest continuously existing American seed business (since 1796), long in decline, was recently purchased by enthusiastic new owners who are making huge improvements.The new Landreth holds promise for gardeners in moderate climates. 650 North Point Road, Baltimore, MD 21237 USA; 1-800-654-2407; www.landrethseeds.com/

Lockhart Seeds, mainly a supplier of farmers in California’s central valley, offers a line of seeds particularly suitable to the Californian homesteader. PO Box 1361, Stockton, CA 95205 USA; (209) 466-4401; no website.

Nichols Garden Nursery, specializing in the unusual and gourmet, has long been in business. 1190 Old Salem Rd. NE, Albany, OR 973211 USA; (541) 928-9280; www.nicholsgardennursery.com/

Peace Seeds, a breeding service and organically grown gene pool for the Cascadia bioregion, is run by my friend Dr.Alan Kapuler. Request his astonishing seed list by post. 2385 SE Thompson St., Corvallis, OR 97333 USA.

Peaceful Valley Farm Supply does sell seeds, but it is listed here primarily for the broad assortment of holistic gardening supplies, organic pesticides, etc., that it offers. PO Box 2209,Grass Valley, CA 95945 USA; 1-888-784-1722; www.groworganic.com/

Renee’s Seeds offers a limited assortment of high-quality, rare, cottage garden seeds chosen by Renee Shepherd, author, expert gourmet cook and gardener. Sales only by internet or seedracks. 7369 Zayante Road, Felton, CA 95018 USA; 1-888-880-7228; www.reneesgarden.com/

Ronnigers Potato Farm has been doing business from a remote valley in the Idaho panhandle for 25 years. It offers about 100 organically grown seed potato varieties as well as garlic and related items. Star Route, Moyie Springs, ID 83845 USA; (208) 267-7938; www.ronnigers.com/

Select is a full-line seed company offering only the highest-quality varieties in substantial amounts in foil-sealed packets at surprisingly low prices (denominated in Swiss francs). Its colorful catalogs are in French or German only, but letters and orders in English are comprehended. Select cheerfully sends catalogs anywhere. Contact:Wyss Samen & Pflanzen AG, Schachenweig 14c, CH 4528 Zuchwil-Solothurn, Switzerland; www.samen.ch/

Importing vegetable-garden seeds

American home gardeners cannot at this time affordably import small quantities of vegetable seeds due to security concerns. Imports now require costly permits and inspections, hurdles to jump whose cost is far greater than any possible benefit.

The United Kingdom is blessed with many excellent suppliers. I find it hard to imagine someone living there having an interest in importing.

Canadians find importing much easier than Americans; however, their own companies do a fine job of serving their needs. Gardeners in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia might find the offerings from the U.K. to be of interest.

Australians can easily import veggie seed in quantities appropriate for the home garden without obtaining permits or following other expensive and awkward procedures — with the exception of four species: corn, beans, peas, and sunflowers. For all other veggies, all that is necessary is that the seed be in packets plainly marked with the correct Latin species name, a usual commercial procedure in any case. Importing is simple: order your seeds; pay by credit card; do not buy restricted species from overseas; await your seeds’ safe arrival by post.

New Zealanders may import commercially sold vegetable seed, in packets appropriate to a home garden, for all species except beans, peas, corn, and beets.The seeds will be inspected by Ministry of Agriculture officials without any charge and released. Any questions should be referred to Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry Imports Management Office, PO Box 2526, Wellington 4-4989624 New Zealand. I have not tried to evaluate domestic New Zealand companies from Tasmania except to note that their prices are enormously higher than those found in North America, even figuring the exchange and postage.

A gardener who has difficulty getting seeds to come up is in a sad way, always needing expensive, unusual, and extraordinary solutions to a problem that shouldn’t exist in the first place.The only conditions in which it should be difficult to sprout seeds are the still-chilled soils of early spring and the high heat of midsummer,when the earth can dry out rapidly.Achieving germination can also be tricky when you’re growing veggies without any irrigation. However, even these stressful conditions can be surmounted with a bit of cleverness.

The best way I know to teach someone how to reliably sprout seeds is to tell them how a germ lab does it. Laboratory germination is accurate and duplicatable: two different germ labs testing samples from the same bag of seed should come up with the exact same result.To achieve uniformity of result, seed technicians have determined ideal sprouting conditions for each type of seed. Their procedure manual prescribes these ideal conditions, species by species.

Germ labs use sterile media (and the best kinds of sterile media), precisely controlled temperature, and precisely controlled moisture. Usually the test is done in a petri dish, a shallow, airtight, clear plastic container about four inches (ten centimeters) in diameter. For most kinds of seed, a technician will take a blotting paper disk slightly smaller than the inside of the petri dish, dip it into water, then squeeze all surplus water out of the blotting paper by balling it up in a fist and squeezing hard. The technician flattens the damp paper circle and places it in the bottom of the petri dish, counts out precisely 100 seeds, and places them atop the moist paper. He or she will then put the petri dish’s cover on and place the dish in a heated box called a germination cabinet. Sometimes slightly better germination can be had by using a light, loose, finely textured, sterilized soil mix (usually consisting of sand, compost, and peat) instead of blotting paper. It is moistened to the same degree you would seek in the ready-to-till test described in Chapter 3.

The germ cabinet temperature is set to the optimum for the species under test. It could be as little as 60°F (15.5°C) for a plant like spinach to as much as 85°F (29.5°C) for okra or eggplant. Usually the temperature is set to be constant. Occasionally it changes regularly: 16 hours at a higher temperature, then 8 hours somewhat lower,much as soil would be when it is heated up with the sun shining on it and then cooled off at night.

The protocol for each species specifies how many days can be allowed for germination because any seeds that might emerge after a certain number of days would be too weak to survive real field conditions. The results of these tests almost always show that the batch that germinates the quickest also germinates at the highest percentage.

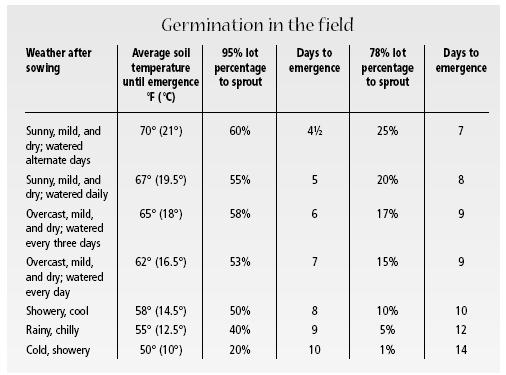

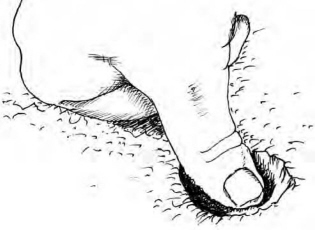

Field conditions are never as perfect as test conditions. Real soil is teeming with microorganisms, some of them hostile to seedlings.The temperature outdoors is never constant and often is colder than ideal, sometimes barely warm enough to let the seed get started. Sometimes the soil can get too hot. And soil moisture is never stable. So germination percentages in the field are never as high as the ones you get in the lab, but there is a relationship, and it is not what a mathematician would call “linear.”What I mean is this: Suppose two lots of cabbage seed are sown at the same time in adjoining rows in the same garden at the same depth. Soil conditions are identical for both. One lot germinated at 95 percent in the laboratory, and all the seeds in that lot had fully developed (root and shoot and two small leaves) on the fourth day of the germ test. The second lot tested at 78 percent, and the last of these seeds weakly finished developing on the seventh day, the last day the protocol allowed.What typically happens in the field is shown in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1

Conclusion: To get the best outdoor germination, start with vigorous seeds and then assist them by creating soil conditions that match as closely as possible the conditions that have been determined to give the best results in a laboratory.

Watering less frequently

It’s natural to fear that if seeds dry out while sprouting, they’ll die. But every time we water, the soil temperature drops, slowing the seed’s progress.Wet, cool soil enhances “damping-off,” a fungus disease that invades and kills the seedling before and after emergence.When the stems of tiny seedlings pinch off at the soil line, you’re seeing damping-off. This disease doesn’t thrive in dryish soil.

Another kind of disease, powdery mildew, attacks members of the cucur-bit family (squash, zucchini, melons, cucumber) in particular. Powdery mildew only thrives in damp, cool conditions. Most gardeners have seen powdery mildew cover the leaves of cucurbits at the end of summer when weather gets cool and humid. Powdery mildew also attacks cucurbit seedlings before emergence.

So it is wise to avoid watering sprouting seeds. But, you ask, don’t seeds need watering?

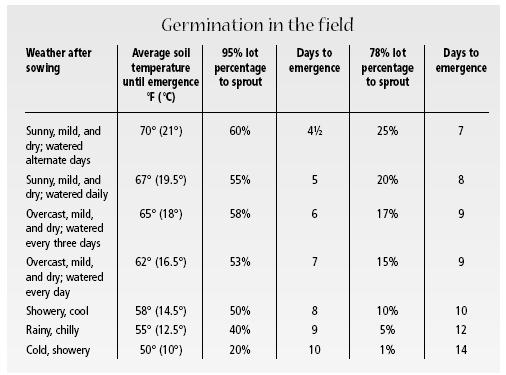

Remember in Chapter 3 when I asked you to pay special attention to the moist footprints in a newly rototilled field? When soil is loosened up with shovel, tiller, or fork, its capillary channels are shattered. Until the soil resettles, moisture is not able to rise from the subsoil to the surface. Seeds dry out quickly in loose, recently worked soil. But what if, instead of cutting a furrow (sometimes called a “drill”) with the corner of a hoe, we made the furrow by pressing the soil down, restoring capillarity immediately below the seeds.This is what I do whenever I sow small seeds close to the surface. I press the handle of my garden hoe down across the bed, making a U-shaped depression about half an inch to three quarters of an inch (1.25 to 2 centimeters) deep. I place the seeds at the bottom of this “U” and then cover them by pushing a bit of fine soil back into the depression.Now the seeds are sitting on top of their own version of a moist footprint, and the loose soil atop them acts to a degree as a mulch, reducing moisture loss. This method has another advantage: the entire furrow is the same depth, resulting in much higher and more uniform germination. If the bed was especially fluffed up, then before sowing I will give it a few days to resettle before pressing a furrow with my hoe’s handle.

Figure 5.2: Making a furrow by pressing down loose soil.

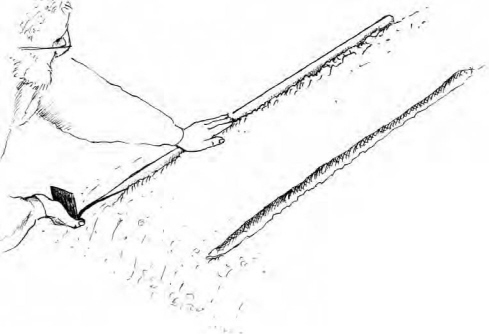

There is another step that’ll also help the seeds. Recall my suggestion in Chapter 3 to rake in compost rather than digging it in, preventing crusting and puddling. This practice also makes the surface layer hold more moisture.

Figure 5.3: Covering the seeds.

In really hot weather this desirable effect can be amplified. Instead of pushing the bed’s humus-rich surface soil back into the furrow atop the seed, why not fill that furrow with pure fine compost? Compost holds several times more water than even clay will. Compost also will almost never form a crust or pose any obstacle to the shoot as it seeks the surface. Seed placed atop moderately compressed soil and covered with compost needs watering far less often, perhaps not at all.

When to water

Watering lowers the soil temperature. If the water is cold, it can take quite a few hours before the sun warms the earth back up.Water evaporating from the soil’s surface also lowers its temperature. This means the worst possible time to water germinating seeds is late in the day. Doing so will leave the bed cold all night, and it will not warm up again until well into the next morning. The best time of day to water a seedbed is late morning, when the sun is getting strong and can reheat the soil as fast as possible. The next best time is midafternoon, when there is still enough time for the sun to reheat the bed before it starts setting.

Chitting

“To chit” means either to presprout seeds or to green-up seed potatoes, getting the shoots to start emerging from the eyes. Chitting brings seed partway through the sprouting process before it is put into the earth. Chitting prevents germination failures.

I mentioned earlier that, while sprouting, the seed first puts down a root to insure it has a moisture supply. Only then does it make a shoot and head for the light. Seeds usually need to be kept moist only until they are putting down their first root. The time required for this to happen depends on the species, the vigor of the particular batch of seed, soil temperature, and weather (if the seed goes into dryish soil, there might be a wait until rain initiates the sprouting process). Suppose you bring your seeds to the point where they have started making a root before you put them into the soil? This is chitting.

When you chit, you initiate sprouting under nearly ideal conditions. Then, after the root emerges but before it gets long (because the root is delicate and snaps off easily), you gently place the sprouting seed in its drill or hill and cover it. Unless the soil is so cold that all development completely stops, within 24 to 36 hours the root tip will have penetrated far enough that the seed will be immune to drying out.

Another advantage of chitting is that you won’t sow dead or nearly dead seed and then go on hoping it’ll germinate, thus losing a valuable window of opportunity. You’re able to observe the initial sprouting process.With most species, if, after moistening the seeds, four or five warm days pass without any sign of a root emerging, you can be pretty sure you’ve got dead or extremely weak seed. If you’ve chitted 20 seeds and only 10 of them sprouted weakly, you know two things: although the germination conditions you’ve provided are not germ-lab perfect, still, 50 percent germination is pretty poor stuff. You’d best start a heap more seeds of that packet because in-the-field performance is going to be poor. Or else try other seed.

Chitting beans and peas. It’s especially helpful to chit beans and peas when you’re sowing early, in soil not yet quite warm enough. Presprouting indoors preserves a lot of the seed’s energy to help it get past the harsh conditions outdoors.

Count out three seeds for every plant you’ll ultimately want, and put them in a glass jar. Soak in tepid water for no more than six to eight hours. Attach a circular piece of plastic fly screen over the mouth of that jar with a stout rubber band. Then drain the water, rinse with tepid water, and drain immediately and thoroughly. Place the jar on its side near the kitchen sink. Room temperature should exceed 65°F (18°C). Twice a day, gently rinse with tepid water and drain. In three to four days, roots should be emerging. Plant them outside before the rapidly developing (and brittle) roots grow longer than the seeds. In each spot you’ll want a plant to grow (the British call this a “station”), gently place at least two sprouting seeds about 1½ inches (four centimeters) deep, if possible with the root pointed down. Cover with loose soil. They’ll be up and growing in a few days.

Chitting cucurbits. Melons and cucumbers are heat lovers; their germ temperature has to exceed 70°F (21°C) and goes best over 75°F (24°C). Squash will sprout at 65°F (18°C) but prefers at least 70°. To hold this temperature I use the same germination box I described in the section on raising transplants in Chapter 3. Some gardeners put the seeds on top of a hot water tank.An electric hot pad set on low might not get too hot for them, but don’t let the temperature exceed about 85°F (29.5°C) or the germination percentage will decline. If it’s warmer than 90°F (32°C), you may kill them.

Fold a section of paper towelling, roughly one foot square (30 by 30 centimeters), into quarters, dip it into tepid water, and let most of the surplus water drip out. Place four seeds for every plant you’ll ultimately want into each of the folds. Place the towelling inside a small, airtight, plastic storage container or a small, sealed, plastic bag and put that in a warm place. After three days, begin checking the seeds twice a day. As soon as the roots are emerging, and before they exceed the length of the seed, plant them. Carefully place three sprouting seeds at each station or hill you’ll want a plant to grow.Gently place the seeds into a small hole about 1½ inches (four centimeters) deep, scooped out of loose damp soil. Try to have the roots pointed down. Cover them with loose soil and do not water unless the earth is bone-dry. Unless you want the seeds to die from cold and/or powdery mildew, do not water until the sprouts emerge. You don’t even want to see rain before then.

Chitting small seeds. Sowing small seed in summer’s heat can be difficult as the surface soil dries out quickly. To give them a head start, place the seeds in a small jar and soak them. Do not submerge the seeds any longer than eight hours or you may suffocate them. Cover the jar with a square of plastic window screen held on with a strong rubber band. Gently rinse with tepid water and immediately drain them. Repeat this rinse and drain two or three times daily until the root tips begin to extend from the seed coats. Then immediately sow the seeds because the emerging roots will be increasingly prone to breaking off and, worse, will soon form tangled inseparable masses.

If the crop will occupy a good many row feet, presprouted seeds that have achieved only slight root development may be poured over a quart (liter) or so of composty soil and then gently tossed like a salad. Sprinkle this mixture into the bottom of a compressed furrow and cover it to the correct depth. If the weather is hot and dry, immediately water lightly and consider erecting temporary shade over the row until the seedlings appear. You will probably only need to water once or twice unless the weather turns scorching, as the seedlings will emerge in a surprisingly short time. This same technique helps get them up and going sooner in the chilly soils of early spring as well.

Getting a uniform stand

If you want many row feet of uniformly spaced carrots or radishes or lettuces, first chit the seeds on your kitchen counter. As soon as they’re barely sprouting, blend the seeds into a homemade starch gelatin. Then, with a few cents’ worth of jerry-rigged equipment, imitate what commercial vegetable growers call fluid drilling.

To make the gel, heat one pint (500 milliliters) of water to boiling.Dissolve into it two to three heaping tablespoons (30 to 45 milliliters) of cornstarch. Place the mixture in the refrigerator to cool.The liquid will set into a gel about as viscous as a thick soup. Don’t let it get cold — only cool enough to set. (You may have to make this gel a few times until you find the correct proportions of water to cornstarch.Too thin and the mixture will not protect the seedlings from damage; too thick and you won’t be able to uniformly blend in the sprouting seeds without damaging them.)

Using a spoon, gently and uniformly stir the sprouting seeds into room-temperature gel soup. Put the mixture into a sturdy, one-quart-sized (one-liter) plastic (zipper) bag and, scissors in hand, go out to the garden. After the furrows have been made, cut a small hole (under three sixteenths of an inch or four millimeters in diameter — better smaller than too big) in a lower corner of the bag.Walk quickly down the row, bent over low, uniformly dribbling a mixture of gel and seeds into the furrow, much as you’d squeeze toothpaste out of a tube. Then cover them as usual.

It may take you a few trials spreading gel without seeds to get the hole size and gel thickness right, but once you’ve mastered this technique, I think you’ll really like it. You’ll need a lot less seed per length of row than you previously did; you’ll get a far higher percentage of emergence, far more quickly; and you’ll save lots of time thinning.

Farmers use some costly and complicated seeding equipment to avoid wasting seed and reduce thinning. Garden magazines and seed catalogs sell various planting machines that don’t work as well as their propaganda suggests. Here’s a technique that does work well and that costs nothing.When sowing small seed in rows, put from a quarter to a half teaspoonful (1.25 to 2.5 milliliters) of seed into a quart or two (one or two liters) of sifted compost or fine composty soil on the dryish side and thoroughly blend the seed in. Then distribute this mixture down the furrow. You’ll do much less thinning.

I know from experience that a heaped quarter teaspoon of strong carrot seed carefully mixed into three quarts (three liters) of fine compost will start two to four carrots per inch (2.5 centimeters) of furrow down about 50 lineal feet (15 meters) of row. There’s no way to be exact about this, however, because the size of carrot seed and the real percentage of seedlings that will emerge varies greatly. Seed size also varies from species to species.Half a teaspoon (2.5 milliliters) of strong lettuce seed might be enough for twice that length of row.

Overseeding and then thinning

Compared to the environmental menaces it faces, a newly emerged seedling is a tiny, weak thing. It has just been through a gruelling, exhausting process not all that different from the birth of a baby. It has run a gauntlet of soil diseases. Plant eaters like slugs, snails,woodlice, and earwigs are waiting to take a chomp out of it. These animals are huge compared to the size of a newly emerged seedling. A few bites can remove so much leaf mass that the seedling dies.

Some new seedlings are always going to die. If you sow one seed and expect to get one plant growing from it, prepare to be disappointed; you’ll soon be going to the garden center and purchasing seedlings. Transplant survival seems far more certain because once a plant has achieved a few true leaves, it is much more immune to predation. Better than transplanting, however, is to sow three or five (or sometimes even more) seeds for every plant wanted. Then when nature kills off a few, you can consider it to be helping you with your task of thinning.

Overseeding imitates nature’s way. But to grow properly, each veggie needs a minimum of space; to grow magnificently, each veggie needs a lot more space than the bare minimum. Crowded radishes will not bulb at all. Crowded carrots mostly develop tops. Densely packed bush beans set small, often tough, and frequently irregular pods that take a long time to pick. Crowded tomatoes, zucchini, and cucumbers stop setting much fruit.

I wish it were possible to produce a packet of 100 percent germination seed from which every seedling becomes a perfect plant. But, alas, this is not the nature of vegetable seeds. It reminds me of the old American legend about Squanto, of the Patuxet tribe, who taught the Pilgrims how to grow corn.“Dig a hole,” he told them.“Put in a dead fish and cover it. Plant four corn seeds well above the fish — one for the worm, one for the crow, one to rot, and one to grow.” Squanto should also have said, “If the one don’t rot or the crow don’t come, there’s thinnin’ to be done.”

I’ve met gardeners who cannot force themselves to thin, which to them seems a cruel act, almost like murdering children. I entreat you, you gentlest of persons, to reconsider the nature of plants. Thinning seedlings is not like drowning unwanted kittens.Vegetables don’t mind being thinned.They actually like it. Thinning helps them. Your vegetables understand you must sow several seeds to get a single plant established because they do the same thing themselves, only more so. In order to get a single offspring growing to maturity, wild plants sow a hundred times more seeds than a gardener will ever sow. And wild plants thin themselves in less merciful ways than the gardener will.

Here are two examples that illustrate what I mean. Consider the propagation of any wild member of the cabbage family. Coles shoot up lanky stalks covered with enormous sprays of yellow flowers. Each flower then becomes a skinny seed pod containing half a dozen or so seeds.These seeds fall to earth and sprout after getting thoroughly soaked.Often all the seeds within a single pod sprout at once, split their pod open by the combined force of their germination, and come up as a little cluster.The seeds within each pod might result from one visit of one bee, but each seed might still be fertilized by a pollen grain from a different plant.Thus every seed in the pod may be genetically different. Cole seedlings are weak and small, but by coming up in a cluster they combine forces. A clump of seedlings may emerge where a single seed would fail to come up. Then each seedling in this group competes for water, nutrients, and light. The most vigorous one dominates the space as the rest slowly die. The winner is the one best suited to reproduce. One wild cabbage plant may have to disperse ten thousand seeds for one to survive and breed.

Now consider how the cucurbit family does it. A wild cucumber or wild melon makes quite a few fruits, each one full of seeds.After the fruit dries out, these seeds sprout in one huge cluster. Like the ones in the cabbage pod, the seeds within that single fruit are genetically different.The one seed that dominates the area is the one that grows to produce more seed next year. All the hundreds of others die after much struggle.

I hope that is sufficient argument to convince you, gentlest of readers, that thinning agrees with nature’s plan. Your way of doing it is, in comparison, quick and merciful.

Generally, you should thin in three gradual steps over three to five weeks. This progressive thinning helps you avoid ending up with gaps in the row even if germination is low, if bad weather slows early growth, or if you lose seedlings to predation. Another general rule: The bigger the seed, the more certain the germination and the smaller number of extra seeds you need to sow for each plant wanted. I always sow two to three large seeds (corn, beans, squash, melons, cukes, radish) for every final plant wanted; I sow four to six small seeds for every plant wanted.When it comes to really tiny seeds like celery or basil, I might sow as many as ten seeds in a cluster at a station where one mature plant will be wanted. Except, that is, when I am sowing pricey hybrids that are sold by count, usually for so much per 1,000 seeds. Hybrid seeds are usually so vigorous (if they are fresh) and so uniform that two or three seeds are enough to start each plant desired when you are direct-seeding.

Where seeds have been sprinkled into furrows (drills), a few clumps of seedlings may need to be thinned immediately after emergence. During their first week, weaker seedlings may thin themselves out for you by falling prey to damping-off diseases and insects.Another week passes, and with most species the first true leaf should be developing.Now is the time to help thin them out so the seedlings stand about one inch (2.5 centimeters) apart. For big seeds, the initial thinning should be to at least 1½ inches (four centimeters) apart.

With open-pollinated varieties, within two weeks of emergence the more vigorous individuals will stand out.At this point, remove the weakest seedlings to give the stronger ones more unencumbered growing room. Should a remarkably vigorous plant appear, pull it out too. It is almost certainly an unintended intervariety cross-pollination, a super-hybrid. It’ll outgrow everything, but what a cabbage-kale cross or a zucchini-pumpkin cross finally produces will almost certainly be disappointing.

Once the little plants are established (three true leaves and growing well), they are relatively immune to sudden loss from insect or disease and may be thinned to the desired final spacing.

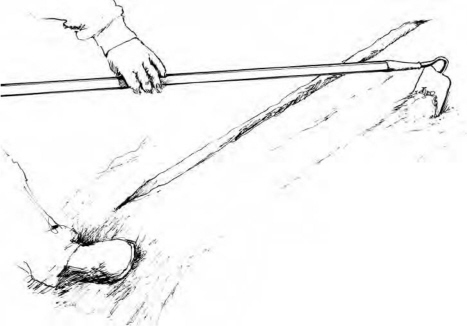

Thumbprints on stations are an excellent way to start small seeds that will grow large plants such as cabbage, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, Chinese cabbage, celery, celeriac, and kale. I will even endure the tedium of doing this for smaller-sized plants, like kohlrabi, when using expensive hybrid seed because the seed cost is high enough to make the extra time spent worthwhile. Spread complete organic fertilizer or chicken manure compost and dig the bed. Let a few days pass to allow the soil to resettle and the capillary connections to be restored. Then place manure/compost on the surface and rake it level.With your thumb, press a small indentation slightly over half an inch (1.25 centimeters) deep.Carefully count out four or five seeds into the bottom of that depression and then cover them with a bit of loose soil. Use a fingertip to trace a six-inch-diameter (15-centimeter) circle in the soil, with that group of seeds right in the center. That’ll mark the spot so you won’t forget where they are. Put these stations on whatever final spacing you want the area to be — 24 by 24 inches (60 by 60 centimeters), or whatever.

Figure 5.4: Making a thumbprint depression for sowing seeds.

As soon as they’ve germinated, thin the clump to the best three or four, and then proceed with the same gradual thinning pattern used for other crops. When what has proved to be the best plant in the cluster has three true leaves, it should stand alone on that spot. If you are sowing tiny seeds like celery, with a naturally low germination rate, make the depression shallower and put in more seeds, as many as ten per spot. And instead of covering them with soil, use a thin mulch of fine compost or aged manure that holds more moisture.

Seedlings should never ever be allowed to strongly compete with each other for light, water, and nutrients. I can’t stress this enough, gentlest of readers. When you sowed those seeds, you undertook to maintain the terms of the contractual agreement we humans made with that species long ago when it agreed to become our vegetable and we agreed to prevent it from having to compete. If you don’t hold down your end of the bargain, the vegetables won’t be able to do their best.

When you allow for seeds that don’t germinate and for thinning, you can see that you’ll be buying at least three or four times as many seeds as the number of plants you want to end up with each year. But you’ll save money if you buy even more seeds and use them over several years. Check the prices in a mail-order catalog that offers more than one size of packets. You’ll see that as the packet size increases, the unit price goes down — a lot. Here’s an example using 2005 prices. Johnny’s Selected Seeds sells a mini-packet containing about 120 seeds of hybrid kohlrabi for $2.85. A thousand seeds of this same variety costs $7.60. If you purchased 1,000 seeds in mini packets, you’d need eight or nine of them, and eight minis would cost you $23.75, not $7.60. Quite a difference! To risk saving this much money you need fair certainty about two things: one, you are going to grow that variety for more than one year; and two, the seed isn’t going to die before you use most of it up. Notice I said “most,” not all.That’s because if you only used half of those 1,000 seeds, it still would work out to be cheaper to purchase 1,000 than to purchase three mini-packets containing only 360 seeds.

I grow a decent-sized kohlrabi patch every autumn, at least 100 of them. To directly seed 100 plants I use 300 seeds. Thus I am certain to use 1,000 seeds in three years. The whole trick is understanding how to preserve their germination.

Assume for the moment that the seed is vigorous, meaning its seed coat contains an abundant stock of high-quality food.The embryo sleeping within the seed will use most of that food reserve to construct a new plant, but some reserves are consumed to stay alive until the embryo does start sprouting. If the seed is stored too long, there won’t be enough reserves remaining to allow the embryo to fully develop when it does finally sprout. In that case the seedling will run out of food and die before it gets established. Starvation can happen in dormancy if you wait long enough. Starvation can even happen after the shoot emerges into the light. If the plant is a “dicot,” the type that starts out with a pair of small fat leaves that don’t look like the next set of leaves it makes (such as bush beans, radish, lettuce, and beet), then it is not capable of producing more food than it is consuming until it has developed its first true leaf. The first true leaf is also built from food reserves. A seedling with insufficient reserves may emerge; sit there with two little leaves, stunned, exhausted; and then, unable to continue, fall over and die. It might seem damping-off or some other disease killed it, but actually it was death by starvation.

How rapidly a dormant embryo consumes its food supply, and how much or little that supply becomes degraded over time, depends on storage temperature and humidity.There’s a rule of thumb about seed storage: Every 10°F (5°C) increase in temperature above what might be called “standard conditions,” combined with a 1 percent increase in the moisture content of the seed, cuts the storage life of the seed in half. On the other side, for every 10°F decrease in storage temperature, combined with a 1 percent decrease in the moisture content of that seed, the storage life of the seed doubles.

Standard conditions are assumed to be 70°F (21°C) with enough humidity in the air that the seed stabilizes at 13 percent moisture by weight, which is what usually happens in a temperate climate. If we could cut the storage temperature to 60°F (15.5°C) and at the same time dry the air a bit so the moisture content in the seeds dropped to 12 percent, the seeds would last twice as long. If you keep the seeds at 80°F (26.5°C) in a more humid environment, where they’ll hold 14 percent moisture, their life span will be cut in half.

If you keep your seeds in a cardboard box in a steamy greenhouse, they won’t last a year. If you keep them on a closet shelf in an unheated bedroom, they will probably last longer than they would at standard conditions.When I ran Territorial Seeds, I knew Oregon’s climate was extremely humid in winter and rather hot in summer. I built a climate-controlled storeroom that held the seeds at 50°F (10°C) with 50 percent relative humidity.At RH 50 percent, the seeds dried down to about 10 percent moisture, so my seeds lasted at least four times longer than if they had been stored under standard conditions. Johnny’s and Park Seed Company do this, too.

One other thing shortens seed storage life: the stress of change. Seeds will do much better if their temperature and moisture content don’t alter.

Here’s how you can keep seeds at home under nearly ideal storage conditions. First, go to a hobby/craft shop or chemical supply house and buy a pound (or a half kilogram) of silica gel desiccant crystals. These don’t cost much. The crystals are usually dark blue when they are dry; the color slowly changes to light blue and then finally to pink after they have soaked up all the moisture they can hold. Silica gel can be reactivated many times as long as it is not heated beyond 230°F (110°C). If the crystals aren’t dark blue, put them into a baking pan, pop this into the oven set over 212°F (100°C) but under 230°F, and bake them for a few hours until nicely blue. As soon as they have cooled a bit, put them into something airtight so they don’t pick up moisture.

Now get some large airtight containers to hold your valuable seeds. I have used one-gallon (four-liter) restaurant mayonnaise jars and half-gallon (two-liter) wide-mouth canning jars. I currently use a large, rectangular, two-gallon (eight-liter), plastic storage box that seals nearly airtight. For each half gallon of seed-storage volume, put in about one cup (250 milliliters) of silica gel. Keep the crystals in a cloth sachet or a small, clear, open-topped container so that you can conveniently monitor their color.This addresses the low-humidity part of the storage. If the gel turns pink, take it out and reactivate it; after cooling it off, return it to the seed container.

The next thing to address is the cool and stable part of the equation. I keep my big plastic tub in the refrigerator. I confess I had to squabble a bit with Muriel — more than once, in fact — to claim half a shelf, maybe one eighth of the entire space inside her refrigerator.The root cellar would also be a good place for this, if you have one. Least ideal, if your partner won’t cooperate and share the fridge, is an unheated room during winter and the coolest place you can find in summer, such as under the house.

There is always more uncertainty about the storage life of seeds you purchased than of those you grew yourself. The seed you buy is new to you, but for how many years, and under what storage conditions, has it been sitting on some seed-warehouse shelf? How much of its potential storage life is left? And how good was that seed from the start? Some years the weather conditions don’t cooperate and the seed fails to fully mature, or it may be rained on a few times while it is drying out, or the field that was used to grow it might not have been as fertile as it should have been.When you grow your own seed, you know a lot more about it.

This is an era of huge controversy about the seed industry’s consolidation, about genetically modified (GM) seeds, about hybrid seeds and heirloom seeds, terminator technology, and patenting, with lawsuits claiming huge amounts in damages from helpless farmers who merely grew a bit of seed. At bottom the issues are about the ability of our system of agriculture to continue if we lose our genetic materials, and perhaps about our enslavement to corporate interests.

All this ruckus provides a business opportunity for politically correct mail-order seed suppliers posing prominently on the side of the angels. Their catalogs suggest that buying heirloom seeds allows gardeners to grow their own. But this claim is not entirely true.With some vegetable species, saving seed is so simple to do and takes so little effort that I’ve wondered why so many people don’t do it. For other species, growing effective seed is a daunting prospect best left to the professional. Easy or daunting is mostly determined by how the species fertilizes (pollinates) itself. Some species self-pollinate; others exchange pollen with neighboring plants (see Figure 5.5).

Self-pollinated species inbreed generation after generation without any harmful consequences.These species are usually quite stable; from generation to generation there is little or no change. To save seeds of these species, you simply save the seeds. A few kinds of self-pollinated vegetables (such as peas and lettuce) have a slight tendency to outcross and should be isolated from other varieties, but 20 feet (six meters) is usually enough separation.All these are fine candidates for saving your own. Seed can be saved from a single plant, and even from a few pods or a single fruit on one good-looking plant, and this can be done year after year, with no problems.

Other species must exchange pollen (outcross) or they become so weak (inbred) they can no longer grow or reproduce. It takes more skill and considerably more land to grow seed for species that must outbreed. First of all, seed raisers must wisely select which plants they will allow to contribute to making seed and which ones they will take out. Selection is necessary to prevent the variety from showing too many unwanted characteristics. But selection must not hold the gene pool too rigorously to an exact form because there’s another pitfall when growing seed from outbreeding species. To avoid what is termed “inbreeding depression of vigor,” the variety needs to have a diverse gene pool composed of plants that are somewhat different from each other. If the seed-making population is either too few in number and/or too uniform in genetics, this line will die out. After only a few generations of inbreeding, a variety can become so weak that its own seeds will barely sprout and will grow so weakly that the variety becomes nonproductive. For a few extremely vigorous out-crossing vegetables that aren’t highly refined, like kale or rutabagas (swedes), the minimum number of individuals needed to avoid inbreeding depression of vigor might be as few as a dozen. For corn, the minimum number of individuals needed to maintain a reasonable level of vigor may be as low as 50. For other species, 200 plants might be the minimum.

Vegetables by method of pollination

| Self-pollinating vegetables (Inbreeding) | Pollen-exchanging vegetables (Outcrossing) |

|---|---|

| Beans | Alliums (onions, leeks) |

| Eggplant | Asparagus |

| Endive/escarole/chicory | Beet (beetroot) and chard (silverbeet) |

| Garlic (no seed) | Brassicas, refined (broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, turnips) |

| Lettuce | Brassicas, unrefined (kale and kohlrabi) |

| Peas | Chinese cabbage |

| Pepper | Corn |

| Tomato | Cucurbits (melons, pumpkins, squash, cucumber) |

| Mustards | |

| Okra | |

| Rutabagas (Swede) | |

| Spinach |

Figure 5.5

Imagine trying to maintain a full-sized cabbage variety when the minimum sustainable number in the gene pool is 200 plants.To allow for weeding out off-types, you’d have to grow a field of 300 to 400 cabbages and select the best 200 for making seed.Do the math: each plant needs a growing space of 4 square feet (0.4 square meters) per plant times 400 plants, which is 1,600 square feet (150 square meters), or 16 beds of 100 square feet (10 square meters) each.Why, that’s two thirds of my active garden beds! And that many plants might make 50 pounds (20 kilograms) of seed. Clearly, growing cabbage seed is something for a market gardener to do as a moneymaking sideline and not something for the home gardener. However, there are some small-sized outcrossing varieties — scallions (spring onions), for example, or kohlrabi or bulbing onions — so for these vegetables a fair number of individuals can be grown for seed on a garden scale.

There is a money-saving strategy for limited home-garden seed production of outcrossing species. Instead of trying to grow seed for a variety indefinitely, start with the highest-quality seed you can buy and then grow your own seed from it, but only for one generation.The seed yield from only a half-dozen plants would supply you (and your neighbors) for a decade. The variety wouldn’t become severely inbred in only one generation, and if some of that seed production were kept under excellent storage conditions, it might last more than a decade, depending, of course, on the species and how vigorous the seed was to begin with. When that lot was used up or lost its ability to germinate strongly, you’d buy another packet of commercial seed and do it all over again.

In Chapter 9 I’ll suggest seed-raising methods for each vegetable. I also recommend two books if you want to grow your own seeds: Susan Ashworth’s Seed To Seed and Carol Deppe’s Breed Your Own Vegetable Varieties. Both are listed in the Bibliography.

Dry and wet seed

There are another two basic vegetable-seed divisions that have nothing to do with their method of pollinating: “wet seed” and “dry seed.”Dry seed forms in pods, in clusters on the stalk, or in the dried flower structures — examples are beans, peas, lettuce, mustard, spinach, beet, okra, etc.Wet seed forms in juicy fruit that is still full of moisture when the seed has matured. These include squash, pumpkin, cucumber, melon, tomato, pepper, etc.

The key to getting vigorous dry seed is to let it mature fully but to keep it drying down steadily while it matures. Should the ripening process continue over weeks, sometimes the only way to keep drying seed from being remoist-ened is to yank the entire plant, shake the soil from the roots, and move it under cover, spreading it out on a tarp or hanging it above one to catch shattering seeds. If the species makes large seed in big pods, such as peas or beans, the gardener can produce seed of a quality no commercial grower could dream of; we can pick each pod at the point in maturation when the stem end of the pod withers and it is clear that the plant’s sap is no longer flowing into that pod. The seed won’t have dried down hard at that stage, but if any further nutrition is added to the seed’s food reserve, it’ll be coming from material held in the pod itself, translocated into the seeds as the pod withers completely. When I am growing bean and pea seed, every day I put a few pods that have dried to the right point into my pocket and take them up to the house to finish drying in a large bowl.

One common mistake made by gardeners growing dry seed is to accelerate drying down by putting the pods or whole plants into an unusually warm place. Remember the data I provided earlier in this chapter about seed life? If the seed is not dry, then it is moist. At high moisture contents and at high temperatures, the seed ages rapidly. It’s best to dry it down on the cool side.

The key to getting vigorous wet seed is to let the fruit become fully ripe on the plant before harvesting it — allow these dead-ripe fruits to continue ripening nearly to the point of rotting on the vine before you extract the seeds. If it is tomato seed, take your seeds from overripe fruit that hid unnoticed, or let a bowl of soft ripe fruit sit on the counter for a few more days before extracting the seed. If it is a melon, make sure the fruit chosen for seedmak-ing honestly slips the vine. If it’s squash, allow the fully ripe fruit to cure in the house for a month or so before extracting the seed.

Seed from hybrids

There is a lot of anti-hybrid seed propaganda in circulation.Much of it is misleading, put forth by people who want to profitably sell you low-quality open-pollinated seeds; some anti-hybrid information is true. I know the anti-hybrid story well. I once ignorantly believed it. But after getting into the seed business, I gradually observed the truth of the matter, as demonstrated on my own trials ground. I also learned a few things from my own breeding work that started with hybrid varieties.

Anti-hybrid propaganda says that gardeners can’t grow their own seed from hybrids. This is a half-truth on several levels.

First of all, hybrid seeds will not replace OP varieties in some species. Hybrids rarely can be mass-produced for species that self-pollinate.The flowers of this type of plant are structured in such a way that they pollinate themselves before opening enough to allow any access by insects. The only way to produce a hybrid variety in one of these species is to perform microsurgery on the unopened flower before it pollinates itself. This is done on hands and knees in the field, aided by a powerful magnifying glass. Each delicate operation will, if successful, result in a few seeds. The making of each seed costs several dollars worth of the breeder’s time. This sort of hybridization is done only to breed new OP varieties.Thus there are no hybrid seeds being sold for beans, peas, lettuce, etc.

But the home seed savers usually concentrate their efforts on just these self-pollinating species because large plant populations aren’t needed to carry the line forward indefinitely.

When it comes to the solanums — tomato, pepper, eggplant — which are also self-pollinating species, there are hybrid varieties that are made surgically, painstakingly, by hand. However, when someone makes hybrid tomato seeds, each pollination results in a hundred seeds or more forming in one big fruit, not six seeds inside a tiny lettuce flower or bean pod. In commercial production, each of the jillions of flowers on a tomato or pepper or eggplant has to be worked over every single morning because each flower must be hybridized before it self-pollinates. As this is done, a little flag has to be tied to the stem of each flower cluster. Hybrid solanums can be produced only where labor costs are extraordinarily low. In the 1980s this was Guatemala. These days they’re being made in China. Even with minuscule labor rates, hybrid tomato seed still wholesales for close to a thousand dollars a pound (450 grams). Hybrid peppers are only a bit cheaper. There are minor advantages to be gained by growing hybrid solanums; they may be a bit more productive and can resist certain diseases better than any known OP variety. Hybrid peppers and eggplants are actually quite useful, maybe essential, in maritime climates where the conditions are so marginal for the species that OP varieties are not productive. Elsewhere, most gardeners have no need of them. The existence of hybrids within these species are not threatening the continued availability of OP varieties.

In some species that naturally outcross, breeders have worked out clever methods of mass-producing hybrid seeds. Commercial growers prefer these varieties because they are more vigorous and perfectly uniform. Despite this kind of seed’s high price, higher yields make the grower more money. Because the economic superiority of hybrids has caused interest in using OP varieties to virtually disappear within the commercial trade, the remaining OP varieties are produced only for the noncritical home-garden market — meaning we gardeners are usually offered degenerated, ragged, low-quality, poorly bred material. For example, there are very few decent OP brassicas offered, although there are a few left. Johnny’s Yellow Crookneck and Costata de Romanesco are the only decent OP summer squash left that I know of.