CHAPTER

8

Insects and diseases

I doubt that in any single lifetime a human could experience the garden pests and diseases found in all climates. I intimately know only the ones in Cascadia and Tasmania. However, having spent decades dealing with these pests, I believe I can also make sensible suggestions about insect problems east of the Cascades and in the United Kingdom, even though I have never personally experienced them.

Avoiding trouble

Sir Albert Howard, founder of the organic farmingmovement, believed that before a plant is attacked, it has already become unhealthy. The plant predator’s purpose in nature’s scheme is to restore balance, like a wolf pack bringing down a sick, old animal that has lived too long. It has become organic-movement doctrine that a truly healthy plant will either be unassailable or will outgrow insect damage and will successfully resist disease. To the organicist, the key is making perfectly fertile soil and, thus, growing healthy plants.

I have noticed a lot of evidence to support this viewpoint. For example, in my variety trials involving eight varieties of Brussels sprouts, all the plants of one poorly adapted variety will be seriously damaged by aphids, while all the plants of the other seven varieties remain almost entirely untouched. In another case, a disease will pick off a single tomato plant, while others of the same variety surrounding and even touching the diseased one will not be affected.This last event leaves me wondering if my distribution of soil amendments was not uniform or if that particular seed was somehow flawed.

In my book Growing Vegetables West of the Cascades I covered one major (often disastrous) regional pest, the symphy-lan, that isn’t addressed in the present book. Symphylans are only experienced as a problem west of the Cascades. I ask Cascadian gardeners to refer to the 4th or 5th edition of Growing Vegetables West of the Cascades (the earlier editions are badly flawed) for a level of specificity I can’t match in a volume that is intended for gardeners in any temperate climate.

Before I learned to directly seed whenever possible, I purchased many transplants. One spring after I’d filled my cabbage bed with garden-center seedlings, three seedlings remained unplanted. For an experiment, I put them into the unmanured fringe of the garden with only a bit of cheap chemical fertilizer for help — no compost, no COF, no lime. As the season went on, the difference was astonishing. Cabbages in the properly prepared bed grew big and healthy, with no problems.The extra three were attacked first by flea beetles and then by cabbageworms, both of which I sprayed.They grew so slowly that I side-dressed them with chicken manure, but the roots were severely attacked by maggots, all three became a bit wilty, and one died from this root loss. At summer’s end the huge cabbages in the garden weighed six pounds (2.5 kilograms) each, and tasted fine; the two survivors on the fringe were one to two pounds (0.5 to 1 kilogram) at best, tough and bitter.

However, even when you provide ideal soil conditions, disease or predation may prevail when you encounter long-lasting poor weather or grow a variety or species not adapted to your climate or soil (like that Brussels sprout variety I mentioned). This can upset people with faith in organic gardening. Organicists also become dismayed when insect populations reach plague levels and the best-adapted variety, enjoying ideal soil and perfect weather, faces troubles that no vegetable can outgrow. An example of this is regularly experienced in the Skagit Valley north of Seattle, Washington, where thousands of acres are devoted to brassica seed crops. The poisons used to protect those plants kill off all natural predators. Consequently, cabbage pests that have developed resistances to pesticides become so numerous that local gardeners must also use effective controls or they cannot grow cole crops. (Note: These controls still do not need to be chemical poisons.)

You eastern American gardeners may consider yourselves fortunate to rarely meet the carrot rust fly or the cabbage root maggot. In Cascadia, fly maggots riddle carrots and leave them inedible; another kind of maggot destroys the root systems of more delicate brassicas and regularly ruins turnips and radish crops. In the fertile Willamette Valley, gardeners have major problems with these two pests; even more so do people in western Washington state. Yet when I gardened in Oregon I had no rust fly trouble and few cabbage root maggots because I lived in the Coast Ranges, worn-out land that was no longer farmed, where the sad-looking pastures were full of wild carrot (Queen Ann’s lace), wild cabbage, and wild radish. Large, stable populations of hosts for these pests also meant large stable populations of their predators.There was plenty for the fly’s larvae to eat outside my garden, and there were plenty of other living things to eat the fly. However, where there are garden carrots but few or no wild carrots, or garden cauliflower but no wild radish or wild cabbage, then the flies can quickly breed into a serious plague that goes entirely unchecked by predation.

My point is that urban gardeners and those living in prosperous agricultural districts are inevitably going to have more problems with pests.Keep this in mind if you’re thinking of buying a new home(stead).

One way backyard gardeners in thickly settled territory can fight back is to increase the numbers of beneficial insects around their gardens by creating proper habitat for them. Someone with a bit of acreage can do a great deal to provide permanent cover that assists beneficials.This is a complex subject that I can’t cover adequately in this book because every climatic zone requires encouraging specific plants that do not also aid insects you wish to discourage. Rex Dufour’s excellent article “Farmscaping to Enhance Biological Control” is available free online from ATTRA (see the Bibliography) and can provide initial guidance.

On the other hand, there’s almost nothing a gardener can do when weather becomes too unfavorable for a species to handle, opening the door to disease or insect attack. I remember well one lousy summer when there were too many cloudy, humid, cool days. My tomato vines steadily weakened, and finally, during the damp chill of what should have been high summer, late blight disease blackened all of Cascadia’s tomatoes.Nearly every single tomato plant, from Canada to northern California, died within a few weeks.The only survivors had been grown in greenhouses or under the protective eaves of a sun-facing white-painted wall, where more suitable growing conditions gave them strength to resist the infection. It helps when you understand this, so that a simple shrug of acceptance is possible. And it is easier to accept weather-related losses if you grow a diverse garden that produces half again more than you’ll need and contains crops that prefer both hotter and cooler weather, a garden that contains a core of really hardy vegetables almost certain to produce something in any circumstance.

Pesticide versus fertilizer

Before you rush to spray poisons, even natural pesticides; before you invest in row covers or rush out to purchase some natural predators; before fighting ... please consider this: Is the struggling plant simply not growing fast enough to overcome the problem? Unfavorable spring weather could be the cause, but sowing too early for the species was your choice, one that retarded growth and lowered the health of the plant. Often the best cure is not “killer” but liquid organic fertilizer — a foliar spray such as combined fish emulsion and liquid kelp (a triple whammy, with two fertilizers, one of which temporarily disguises the plant’s odor from predators). Maybe a bit of spot fertigation will save the day.Maybe in a week or so growing conditions will improve, the soil will warm up, nutrient release will accelerate, and everything will come right.

Figure 8.1: Spot fertigation.

Also, it’s wise in such circumstances to take out insurance: immediately sow again! And sow a bit more thickly this time.When weather conditions are unfavorable, if you start many more seeds than the final number of plants ultimately wanted, you can have a relatively benign attitude as insects and diseases help thin out the weaker seedlings. This later sowing may grow faster from the start and end up yielding sooner than the earlier one.

Speaking of a benign attitude, remember my comments in Chapter 4 about buying seedlings at the garden center? It’s easy to be relaxed about abandoning some seedlings when the seeds only cost you a few cents each, but it’s much harder to be dispassionate when seedlings that cost a few dollars apiece are being knocked over.

As a last resort, pesticides (preferably natural substances and not dangerous chemicals) may provide a short-term solution while you wait for spring weather to moderate and growth to resume. Besides, in spring the plants are tiny, so only a little dab of poison here and there is needed. And nothing is blooming; you won’t risk killing pollinating bees.

Spun-fabric row covers provide most of the benefits of a cloche or mini-greenhouse without your having to erect any structure. They also provide protection against flying insect pests without your having to spray. Several brands are available; all are about five to six feet wide (150 to 180 centimeters) and may be offered in cut lengths starting at about 20 feet (six meters) up to industrial-agricultural rolls thousands of feet long designed to be reeled out behind a tractor. These spun fabrics are not completely transparent. The amount of light lost varies by make, as does their longevity and durability.

The fabric is spread over a growing row or bed and loosely anchored with a sprinkling of soil. As the plants grow, they lift the almost weightless fabric so no supporting structure is required. To keep insects out, the entire perimeter must be carefully anchored with soil, leaving no cracks or openings. Neat stuff!

One brand, Reemay, provides a few degrees of frost protection and considerably increases daytime temperatures, enhancing springtime growth. However, Reemay also decreases light transmission by 25 percent — not a desirable side effect. Other brands weigh less than Reemay, are less abrasive to plants when it gets windy, do not reduce light transmission as much, and do not cause any heat buildup in summer — but may not last as long.

On the downside for all these products, they are usually made with oil or natural gas as feed-stocks, are expensive, and can’t be counted on to last more than one season, even with gentle handling.

Weather and decreasing light levels at summer’s end can also prompt troubles with diseases and insects on heat-loving crops. These are hardly worth fighting, since the plants’ life cycle is virtually over anyway. But if you find yourself fighting for a crop from start to finish, either something is wrong with your soil management, or else the crop is one that you should not be attempting on your soil type or in your climate.

Certain vegetables are fussy about the type of soil they will and won’t grow in. These species may express their difficulty by being susceptible to insects or disease. This is especially common with weakly rooting species intolerant of clay soils, such as globe artichoke, celery, celeriac, melons, and cauliflower. Brussels sprouts are the opposite; they don’t like to grow in light soils. If they are planted in such ground, the sprouts tend to blow up and be loose, and the tall plants fall over.

Gardening aikido

My wife, Muriel, and I believe that when one of us annoys the other, this irritation, rather than being an excuse to throw blame around and have an enjoyable fight, is an opportunity for the annoyed person to clean up some of his or her own rough edges.After all, if I didn’t have something in my own character similar to what is irritating me, I wouldn’t be bothered much when I see this trait in another.

I will confess here that I cannot raise decent celery. I could claim that a stalk-invading disease always cripples my crop about when the plants have grown to a foot (30 centimeters) tall. More likely what is really happening is this: The top foot of my garden is a magnificent loam; under that is a fairly dense clay. Celery won’t root in clay, period. But the root systems must eventually enter that clay if growth is to continue. The roots can’t enter the clay, growth virtually ceases, health ceases, and a disease organism arrives to pick off the weak members of my herd. There is little or nothing I can do short of creating a deep bed of special soil or selling the property. Shrug!

In much the same way, I try to see pests as guides to becoming a more skilful grower.One important step along this path is abandoning what self-help psychologists and some preachers call poverty consciousness. Instead of planting a garden from which you’ll only harvest exactly what you want if everything goes well, plant twice as much as you need, so that pests and diseases could wipe out a third of the garden without stopping you from giving away buckets of food.

Some years just are difficult years: the sun doesn’t shine often enough, it rains too much or not enough, the tomatoes get blossom end rot, melons and cucumbers succumb to powdery mildew or beetles, eggplants won’t set or get covered with red mites, peppers get some virus the extension office never saw before, corn is late and not as sweet as you remember it and the last sowing fails to ripen before frost comes, snap beans are covered with aphids, cabbages are covered with aphids, Brussels sprouts are covered with aphids, aphids are covered with aphids. But if you planted twice what you needed, there will still be enough.

I have pointed out several times that planting too early is the biggest single cause of trouble, but I need to say one more thing about this. I call your attention to the fact that growth rates accelerate hugely as the soil warms up. Sowing on the first possible day that the species could germinate or survive if transplanted, and sowing again two weeks later, will result in two crops with only a few days’ difference in maturity. But the crop sowed two weeks later will have a lot less trouble. You will soon see from your own experience that I am speaking the truth here.

Another way to avoid battling is to reconsider the American Sanitary System (ASS), something Everybody Else believes in. Everybody Else’s ASS suggests that food should be “clean” and free of bugs. The belief system is so widely held that no one in our supermarkets would buy spinach with a few holes in the leaves or a rutabaga (swede) with a few scars on the skin. Imagine the horror of finding a blanched cabbageworm in a frozen broccoli packet!

Why not change your attitude about what constitutes acceptable table fare? Remove as many bugs as possible when the food is washed, and then discretely slide the rare insect that escapes the cook’s scrutiny to the side of your plate. Remember, there’s a big difference between a plant showing the odd hole from an occasional insect and one that has been severely damaged. As long as the plant is still growing vigorously, a few (even a few hundred) pinholes in the leaves — or a scar on the cucumber’s skin — don’t matter.The critical level of leaf damage,where production and quality start to lessen, is a loss of about ten percent of leaf area.The critical level where aphid infestation has become too much is when they cover about 5 percent of the entire plant. As long as the cook can peel an occasional scar from the skin, why even bother to oppose the pest committing that minor nuisance? Let commercial farmers fight bugs on behalf of their unrealistic clientele.

Insects and their remedies

Aphids (Aphadidae family)

Often called plant lice, these are small, soft-bodied insects that cluster on leaves and stems, sucking plant sap. A few cause no significant damage unless they transmit a virus disease. In large numbers they cause leaves to curl and cup and can weaken or badly stunt a plant. Aphids can multiply with amazing rapidity, exploding from nothing to a serious threat in days. But they can also persist at a low level without causing much trouble. Don’t rush to fight them the first time you see a few. To stop disease-carrying aphids from infecting your plants, you would have to spray something that would kill every single one before it entered your garden, and that’s not possible! It’s better simply to make your plants healthy enough to resist most diseases most of the time.

Aphids sometimes have a close relationship with ants, which “farm” them much as humans graze cows on pasture.Ants place aphids on leaves and then milk a sweet secretion from their livestock.Aphid control may entail elimination of ant nests.

You can spray aphids off leaves with a hose and nozzle.The ones you blast off will probably not find their way back, although others may. Safer’s soap (a North American insecticidal soap made from special fats) is effective and virtually nontoxic to animals and most other insects, although it can burn the leaves of delicate plant species (I’ve especially noticed this with spinach) if used in strong concentrations. If you suspect you’re going to have to use Safer’s, test a bit on a single leaf a few days before you spray the whole patch. With Safer’s, you also need to experiment with dilutions; it often works fine in greater dilutions than recommended, and when it’s weaker it is easier on delicate plants. Australians have long used ordinary soap for this purpose — the traditional brand is Velvet, made from only tallow and lye.Americans have one like it called Ivory. The concentration required is about what you would use to wash dishes. When Muriel was a child-gardener, her family killed aphids by pouring the precious leftover dishwashing water over the plants. Preparations of rotenone plus pyrethrins appeal to people who enjoy killing bugs because just about anything hit with this combination drops dead almost instantly; both are natural poisons that (unfortunately) decompose in the environment within hours. This mix also kills bees and beneficials. The final remedy I recommend is neem spray, a long-lasting natural oil from a tropical seed.

Cabbage maggots (Hylemya brassicae)

See Root maggots, below.

Cabbageworms (Pieris rapae) (Trichoplusia ni)

There are at least two distinct species. Maybe four. The large green ones are larvae of a white butterfly often seen fluttering about the garden. Their clusters of small, yellowish, bullet-shaped eggs are laid on cabbage family plants, usually on the undersides of leaves.

A similar pest, sometimes called the cabbage looper, is a smaller larvae of a night-flying brown butterfly. Its round, greenish white eggs are laid singly on the upper surfaces of leaves. The larvae hatch out quickly and grow rapidly while feeding continuously on brassica leaves.

Both species can do a great deal of damage in a short time, especially if they begin feeding at critical times (such as during the early formation of cabbage heads) or if their numbers are excessive. Surprisingly, the small larvae of the night flyer are usually more destructive than the large ones of the day flyer.

In a small garden, handpicking and tossing the larvae away from any cabbage family plant can be sufficient control. An extremely effective nontoxic pesticide called Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is widely available, often marketed as Dipel. Bt can be sprayed the day of harvest because it is lethal only to the cabbageworm, cabbage looper, and a few close relatives.The culture remains active on the leaves for only a week or so, but even if sprayed only once, it seems to persist in the garden at a low level as infection is transmitted from decaying infected worms to healthy worms, significantly reducing their numbers for the rest of the season. If resprayed a few days after every rain or overhead irrigation, Bt can satisfy finicky growers who become grossly offended at the idea of a cabbageworm appearing in their broccoli or cauliflower heads.

Cabbage family plants usually have rather waxy leaves; sprays tend to bead up and run off of them. It is essential to put some sort of water softener (spreader/sticker) into the spray tank when using Bt. I use a quarter teaspoonful (1.25 milliliters) of cheap dishwashing liquid per quart (liter) of spray. It is also wise to spray the undersides of leaves as much as, or more than, the tops.

Carrot rust fly (Psila rosae)

See Root maggots, below.

Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata)

Found almost everywhere in North America, this beetle can almost completely defoliate a commercial potato crop. It may feed on other solanums (i.e., peppers, eggplants) and assorted weeds and flowers.The adults overwinter 12 to 18 inches (30 to 45 centimeters) below the surface in or close to the potato plot. Late in spring they emerge, lay eggs on the undersides of leaves, and resume feeding. Then their larvae also begin feeding.

If you grow spuds on a new piece of ground, few beetles will emerge immediately in the patch, which means row covers can be an effective defense.

Growing spuds on new ground is a good idea anyway, as it reduces disease problems, especially “scab.” Straw mulching (using wheat or rye) after the seed has been planted has been proven to greatly reduce problems by providing habitat for beneficial predators that feed on both beetles and their larvae.However, this practice, which might work for the large-scale market grower, restricts your ability to hill up by hand hoeing (see Chapter 3), which helps prevent green potatoes and increases the home gardener’s yield.What a conundrum!

In northern North America the beetles go through one egg-laying cycle each year; but in the southern United States they may go through as many as three. Getting the crop in early and growing early-maturing varieties may help southerners get the harvest in before the beetles get too thick. Rotenone/ pyrethrum is effective for about two days and may be repeatedly sprayed, but it also kills beneficials — and in the long run, regular use of any poison works against the grower.

There are biological pesticides, but they have limited effectiveness.One is a strain of Bacillus thuringiensis that kills only potato beetle larvae and only when they are young. To make it work, you must watch closely for hatching eggs and then spray. There are more broadly effective fungal antagonists, and certain strains of parasitic nematodes have also been effective. Finally, for the home gardener who can spend more money than the entire crop is worth, there are flamers that lethally burn the beetles and their eggs off young plants.

The best and most affordable methods for the home gardener are to make sure there is lots of habitat around the veggie garden for beneficials and to spend a few hours handpicking adult beetles, especially attempting to eradicate them when they first emerge in spring, before they lay their eggs.

Corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea)

A close relative of the cabbageworms, this pest is also known as the tomato fruitworm because late in the season,when corn is not attractive to it, the insect may become a minor nuisance on tomatoes and, sometimes, snap beans. It usually does not survive freezing winter, so it only becomes a pest in the north of North America late in the season, after it has flown up from farther south.

Food of choice for the larvae is ripening corn seeds; in California I have seen them eat more than the top half of an ear before it was ripe enough for me to try eating the bottom half. I’ve also seen a few in Tasmania, but not enough to bother fighting them.

The rather plain-looking small moth lays its eggs on the green silks of the corn plant. The larvae hatch out and follow the silks into the ear, fouling the ear with their excrement as they eat their way down the cob. Control is simple, effective, but a bit painstaking. Shortly after corn pollination is finished, mix a double-strength batch of Bt (with a spreader-sticker) and then, using a soft brush, generously daub this mixture on the silks of each ear. You could also make a blend of dormant oil (white oil), water, and Bt.

Cucumber beetles (Striped: Acalymma Vattatum Trivittatum) (Spotted: various species of Diabroticae)

Adults of all types of this North American pest are about a quarter inch (six millimeters) long.The striped ones have three parallel lines running the entire length of their back from head to tail; the Diabroticae have various patterns and colors of dots on their backs. Both species overwinter in the south and emerge in spring. In the north, the striped beetles overwinter while the spotted ones, strong flyers,migrate from the south, appearing about May/June.Winter/spring weather conditions can greatly alter their numbers. Some years are difficult for the gardener; some easy.

Overwintering beetles damage spring seedlings, chewing on leaves. Their larvae then proceed to feed on the roots, somewhat stunting the plant. The beetles prefer to feed on cucumbers. Their next favorite meal is cantaloupe and other similar melons, then squash, and watermelon last. There are also varietal differences in beetle interest.

If you have severe and repeated trouble, I suggest you do variety trials or consult your local agricultural agency about the best varieties for your area. Some years this damage can seem catastrophic.Many years it is minor. Emerging or migrating adults usually do minimal damage unless you are a market producer; they may scar skins of fruit or otherwise reduce the yield somewhat.

You can deal with this pest without directly fighting it. The easiest strategy is to be a few weeks later than most in your area to sow all cucurbits.This lets the seedlings get growing more vigorously, minimizing the significance of beetle damage.Another tactic is to plant four seeds, thinning to two plants per spot only after the seedlings have made a true leaf and are growing fast. (Where beetles are not a problem, one surviving plant per spot or hill is a far better practice.) Overwintering beetles sometimes transmit a virus wilt disease that kills seedlings. If a seedling does succumb to either predation or virus, there will still be growing time, in all but the shortest-season areas, to sow another in a different spot; the worst of the predation should have passed by then anyway. Excessive soil nutrients make seedlings more succulent and thus more attractive to beetles. And greenhouse-grown seedlings are always lush and succulent, having been pushed to achieve maximum growth rates.

This case supports my contention that direct-seeding, a bit on the late side, is the best practice.

Putting each hill of emerging seedlings under a carefully anchored square of floating row cover will keep the beetles away until after they have laid their eggs.When the vines begin blooming you can remove the cover, allowing bees access to the flowers. Parasitic nematodes will control the larvae if you apply them to the root zone of small seedlings by mixing a dose of nematodes into a few quarts (liters) of water and fertigating the vine with them. However, these sorts of controls often cost more than they are worth.

Finally, the experts, each probably having read Everybody Else’s manuals, recommend thorough cleanup of cucurbit residues, but I fail to see how this will do much good, considering the life cycle of the pest. If the larvae do mature, they’ll overwinter under any available cover and won’t need dead cucurbit vines for this purpose.

Flea beetles (Phyllotreta striolata)

These tiny, black, hopping insects chew pinholes in leaves, mainly in small members of the cabbage family, but occasionally they’ll feed on other vegetables.

In high numbers, flea beetles stunt and kill seedlings. Fast-growing, healthy plants usually aren’t significantly perforated; tender greenhouse seedlings often have a hard time because they’re in shock, not having been hardened off before being set out.

In early spring, overwintering adult beetles migrate into the garden from surrounding fields and begin feeding. Later in spring, the adults lay eggs in the soil.These eggs hatch into soil-dwelling larvae that feed on various roots, usually without doing much damage, until they pupate. After maturing into adults, the beetles then continue to feed until they hibernate in fall.This later feeding is usually of no consequence.

Flea beetles seem a pest only in spring when, due to cool conditions, plants are not growing rapidly and the garden is mostly bare, forcing many of them to concentrate on a few seedlings. Husky, well-hardened transplants normally outgrow flea beetle nibbling. Problems may be prevented by directly sowing five seeds for every plant wanted and then thinning only as competition starts to affect their growth.This gives the beetles more to chew on while providing the gardener with enough vigorously growing survivors to establish a stand. It is also wise not to sow at the earliest possible moment.

Keep a close eye on spring brassicas. If seedlings are losing more than 10 percent of their leaf area, the best first remedy may be a foliar feeding of fish emulsion (the foul smell of which might also confuse the beetles for a few days while the seedlings get going again).

If the loss of photosynthetic surface exceeds 20 percent, I suggest spraying every few days with rotenone or a liquid combination of rotenone and pyrethrum. Once weather moderates, the problem should go away.

Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica Newman)

Mostly located in the northeastern states of the United States, this pest is steadily spreading west and south. Its major economic damage so far is to turf, although it feeds on many kinds of plants. The beetle goes through one egg-laying cycle a year and spends perhaps ten months each year in the soil. The adults emerge in late spring and are gone within a few months, having laid their eggs.

You can spray adults feeding where they are unwanted with rotenone. However, they are unlikely to cause major damage in the veggie garden. If the larvae are feeding on vegetables’ roots, it may not be easy to identify them as the culprits. There are strains of Bt and other biologicals specific to this pest that can be mixed in water and poured on the soil.

Japanese beetle traps can significantly reduce this pest’s population levels if the entire neighborhood cooperates and everyone traps them. I stress“entire” because the adults are strong flyers.

Leafminers (Liromyza spp.)

See Growing Vegetables West of the Cascades.

Root maggots (Hylemya brassicae, Pisla rosae)

These larvae of innocent-looking small flies are only a major problem in Cascadia and the United Kingdom. I can’t begin to tell you what a relief it is for a cabbage lover like me to live in Tasmania, a place where the weather is like Oregon’s, but neither of these pests are present.

The cabbage fly waits until the root system of a brassica has become extensive enough to support its brood (this is about when the stem approaches a quarter inch — six millimeters — in diameter) before laying its eggs on the soil’s surface near the plant. After hatching, the larvae burrow down and feed on the roots. Weaker-rooting brassicas — i.e., small-framed cabbage, most broccoli varieties, and all cauliflower, but rarely Brussels sprouts — become wilty.They may collapse and die or become stunted and barely grow.Maggots also tunnel through turnips, radishes, and the lower portions of Chinese cabbage leaves, although they tend to leave rutabagas (swedes) alone or at most scar up the thick skin, which is peeled away before cooking.

Some cole varieties have stronger root systems that tolerate a certain amount of predation without the plant wilting or becoming noticeably stunted. That’s why I always did brassica trials without maggot protection. A magnificent result is when eight out of ten varieties are demolished by maggots and two varieties seem unscathed. In the case of radish, turnip, and Chinese cabbage, varietal choice provides no relief. Your only options are to use row covers or to undertake a timely harvest that gets them out of the ground before the maggots have invaded many roots. Unfortunately, “timely” harvesting is not an option with Chinese cabbage.

Gardeners can avoid much trouble by planting after the spring population peak. By early summer the spring maggots are pupating harmlessly in the soil. Mid- to late-May through July is the best time for North Americans to sow brassicas.Maggot levels increase again in late summer when the pupae hatch out, but by then non-root brassica crops are usually large enough to withstand considerable predation, and light intensity has dropped so much that even if plants do lose some root, they are not likely to wilt. Unprotected radishes, turnips, Chinese cabbage are still ruined.

In North America, this pest is a major problem only in Cascadia. Elsewhere it is a minor annoyance.

The late Blair Adams, research horticulturist at the Washington State University Extension Service in Puyallup, did extensive trials on a number of traditional organic remedies for root maggots. He found that dustings of wood ashes or lime — once widely recommended — actually attracted cabbage flies.He speculated these remedies helped despite that because in the (unlimed) acidic, calcium-deficient soils typical of Cascadia, the calcium-rich wood ashes boost the growth of brassicas enough to compensate for the increased predation the ash caused. Blair also found that careful and persistent hilling of soil around the plants’ stems increased the survival rate of seedlings somewhat by burying the root system deeper.

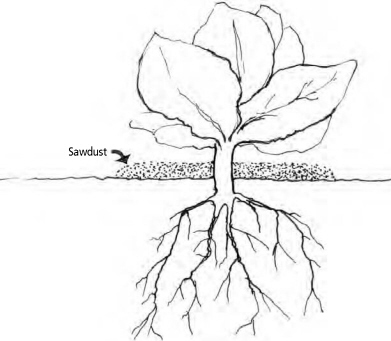

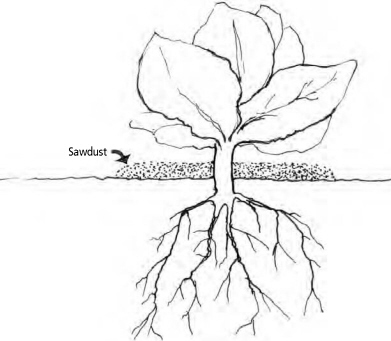

The best simple organic control Blair could come up with was the collar. Gardeners had long used about a square foot (900 square centimeters) of tarpaper with a slit cut halfway through it so it could be fitted tightly around the stem, effectively keeping the fly away from the soil, but Blair felt that sawdust worked better and was easier to apply. A ring of fresh fine sawdust about 1½ inches (four centimeters) thick, six to eight inches (15 to 20 centimeters) in diameter, touching the stem, will prevent the fly from laying its eggs on the soil’s surface.To protect radish and turnip, sow the seeds on the soil’s surface, cover the seeds with a band of fine sawdust four to six inches (10 to 15 centimeters) wide and one inch (2.5 centimeters) deep. Timely harvest is still essential because the swelling roots push the sawdust aside and expose themselves to the fly’s rapidly hatching eggs.

Since Blair did his work, another organic remedy has become available. Certain species of parasitic nematodes effectively attack root maggots in the ground. If large numbers of these microscopic life forms are seeded into the soil surrounding brassica seedlings, they can live for months, breeding and maintaining fairly effective population levels for a while, and actively knocking off maggots as fast as they hatch out. Parasitic nematodes will also control numerous other pests including wireworms, onion maggots, carrot weevils, cutworms, rhododendron root weevil larvae, strawberry root weevil larvae, and cucumber beetle larvae.

Parasitic nematodes are easy and cheap to culture by the billions, but it’s not always so simple to transport or store them alive once they’re out of the culture medium. Be cautious if you’re buying them and make sure what you’re getting is fresh and remains effective.

Figure 8.2: A sawdust collar that protects brassicas from root maggots.

Floating row covers that are carefully anchored on all sides will effectively prevent cabbage root maggots from reaching plants. These are especially useful for Chinese cabbage and turnips.

The carrot fly maggot is a similar Cascadian (and British) pest that gardeners in eastern North America are fortunate to rarely encounter. Although I gardened in Oregon for many years, I have little personal experience with this critter, although I know people who lived only 40 miles (65 kilometers) from my garden who had serious problems.The fly begins breeding in late summer, going through a generation every month and becoming a plague by winter if the season is not too severe. Carrots started in late May come up after the spring hatch is through; these may finish growing relatively unharmed and be harvested by late summer. However, carrots left in the ground after summer ends become increasingly infested as the fly population grows a hundredfold or more each month into autumn and early winter.

Parasitic nematodes are useless because this maggot is most active when soil temperatures are low and nematodes are inactive. Covering the bed with meticulously anchored spun-fiber row covers may give you a maggot-free crop.When the tops are three or four inches (7.5 to 10 centimeters) tall, thoroughly thin the carrots to about 150 percent of their normal spacing (to allow for the loss of light through the fabric) and at the same time eliminate every weed, then carefully cover the bed. Gardeners have used homemade solutions similar to this for years, placing large, lightweight, wooden frame boxes covered with fly screen over carrot crops to prevent the fly from laying eggs.

Store carrots during winter by carefully laying sheets of plastic over the carrot tops and covering that with a few inches of straw or soil for insulation. This might prevent the fly from gaining access, through it may also make a haven for field mice, who enjoy carrots as much as humans do.This works in Cascadia because severe freezing conditions are rare, and when they do happen, they normally last only a few days.

Slugs and snails (Gastropodae)

See Growing Vegetables West of the Cascades.

Symphylans (Scutigerella immaculata)

See Growing Vegetables West of the Cascades.

Squash borer (Melittia satyriniformis)

Found everywhere in North America east of the Rockies, the borer can be highly destructive because a single one can cause the loss of an entire plant or collapse a long runner. The adult moth emerges from the soil in spring and lays eggs singly near the bases of numerous squash plants, continuing until she has laid as many as 250 eggs. A few dozen moths are capable of infecting an entire commercial pumpkin field.Hatched larvae enter the plant, usually near the base (the entrance hole is marked by a gob of what resembles sawdust), and inevitably tunnel “upstream” toward the center, destroying the vascular system and causing that runner (or the whole plant) to wilt and die.Occasionally one enters a leaf stem. Tunnelling goes on for four to six weeks. If the vine dies before the borer completes its life cycle, it can migrate to another plant and start again. Because it is protected inside the vine, a borer is difficult to eliminate with organic pesticides. I suspect the borer is the reason that squash is traditionally grown several plants per hill — as insurance — even though all cucurbits grow much better if only one plant occupies each hill.

The borer prefers squash and pumpkins; usually it has little interest in cucumbers or melons. Butternuts, Green-Striped cushaw, Yellow Crookneck, and Dickinson pumpkin all have proven resistance to the borer. Gardeners should patrol their plants every few days and carefully inspect them for signs of borers, although it can be difficult to closely examine bush summer squash of any size. For that reason the sprawling heirloom Yellow Crookneck might be the best for the garden; that variety also shows the highest resistance to the cucumber beetle.

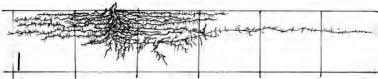

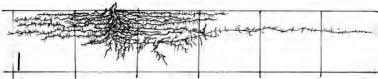

If you discover signs that a borer has entered a plant, you can destroy it by slitting the vine, starting at the entry hole and cutting toward the center of the plant. If it is a vining squash, toss a shovelful of soil on top of the vine at the cut to accelerate healing and cause secondary roots to form there. Some gardeners routinely toss a shovelful of soil atop many points where leaves emerge from vines.This encourages secondary roots to form at each point, so if a borer does manage to invade, it cannot collapse the entire runner or entire plant because it will have multiple root systems. Do not miss any opportunity to destroy a borer; there usually aren’t many adult moths causing all the trouble.

Figure 8.3: Typical secondary root originating from the leaf node of a squash vine. It is only partially developed. Each square is one foot (30 cm) per side. (Graphic adapted from Figure 89 of John E. Weaver’s Root Development of Vegetable Crops.)

Plot rotation does not help because borer moths may fly as far as half a mile (800 meters) to lay eggs.After harvest, promptly burn winter squash vines or move them to the core of a hot compost heap to prevent late-maturing borers from pupating. If your growing season is long enough, later planting may allow you to evade the moths, which only fly and lay eggs for a short period. The local agricultural extension office may suggest a safer sowing date.Having fertile soil under the entire spread of the vine is helpful, as a vigorously growing vine can tolerate a few borers, especially if it forms secondary roots in many places. Some gardeners use a large syringe to inject Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki into the stem of the plant. In an attempt to kill borers emerging from the soil before they get into the plant, some gardeners repeatedly spray rotenone/pyrethrum, confining it to the base of the stem. Do this late in the day because this spray combination is highly toxic to pollinating bees.

Squash bug (Anasa tristis)

Squash bugs are easily recognized. They’re about five eighths of an inch (1.5 centimeters) long, dark brown or mottled, and give off an unpleasant odor. Children call them stinkbugs.The adults and their larvae suck plant juice and inject a toxin that causes plants to wilt. Individual runners may blacken and die back.The effect resembles a bacterial wilt, but when the bugs are brought under control, the plants recover. They are considered the most destructive North American cucurbit pest.

Adults overwinter under whatever cover is available, emerge in spring, and begin feeding and laying eggs. The eggs are easy to spot: orange-yellow, a sixteenth of an inch (1.5 millimeters) long, placed in neat rows on the undersides of leaves. Upon hatching, the larvae start feeding. Egg-laying can continue well into the summer. In the south, squash bugs can go through two generations each summer, increasing to huge populations.

The first step to reduce the problem is end-of-season sanitation, leaving as little cover (such as old boards on the ground and dead plant residue) as possible. Prompt and thorough composting of all squash vegetation in the core of a hot compost heap is helpful. Also dig up the root mass at the center of the vine and compost that, too. The home gardener’s remedy is to thoroughly and repeatedly handpick stinkbugs. Remove and burn leaves showing eggs, or zip them up in sealed garbage bags.

The amount of time these actions take would make most people think of pesticides, but in this case pesticides are not useful. Biological pesticides are effective only against small-sized larvae, and because egg-laying goes on for several months, because most organic pesticides last only a short time, and because the vines grow rapidly, these pesticides have to be repeatedly sprayed on the undersides of leaves (in itself not an easy task to accomplish). Chemical pesticides kill bees pollinating the flowers. There are numerous beneficials that eat squash bugs or their larvae; spraying poisons kills them off, too.

The gardener’s best options are to grow a mixed garden offering lots of cover for beneficials, including some stands of buckwheat to harbor tachinid fly parasites, and handpicking.

Squash bugs have varietal preferences, though research reports on these are mixed and somewhat contradictory. Gardeners will have to work this out for themselves.

Diseases and their remedies

Sadly, the home gardener has no effective cure for plant diseases.However, we can often prevent the problem by growing healthy and naturally disease-resistant plants, which means using appropriate varieties and making highly fertile soil. If disease does strike, keep in mind that some years the weather can be so unfavorable for certain types of vegetables that almost any variety will be weakened to the point of becoming sick.

The best first step when some plants are getting diseased or when the weather turns against you is to spray your garden with liquid kelp,which provides a tonic of trace minerals and other fortifying substances that improve plants’ overall health. In the same vein, Dr. Elaine Ingham, an Australian at Oregon State University, has been spraying teas brewed from high-quality composts. She finds compost teas cover the plant with beneficial microorganisms, and for a week or so after spraying they will prevent disease organisms from gaining a toehold. However, this practice is not simply a matter of dumping any old compost into a barrel and brewing up some “tea,” filtering it so it won’t clog the sprayer’s nozzle. The compost has to be quality stuff, expertly made. The ratio of manure to vegetation, and the quality of that vegetation (i.e., how much woody matter does it contain and how much green stuff ), may determine which diseases the tea will control. Still, if you make decent compost, it is worth a try to see if yours will serve this purpose (see Chapter 6 for a compost tea recipe). If you make good compost, you might want to do an Internet search for “Elaine Ingham” or “compost tea” and see what comes up.

Regular (weekly) foliar feeding of vegetables is a good idea in any case. It doesn’t cost much. Every gardener should experiment using homebrewed compost/manure teas, liquid kelp, and fish emulsion sprays.Those who don’t practice the organic faith might find great benefit from spraying hydroponic nutrient solutions as foliars.

Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew (PMD) covers the photosynthetic surfaces of the leaf with a grey cast and interferes with food making. It quickly kills most plants it attacks.

Here is one case where the gardener has an effective way to stop the disease in its tracks; however, the remedy is quite short-lasting and requires painstaking attention. Spray infected plants with a solution of one measured teaspoonful (5 milliliters) of baking soda per quart (liter) of water, adding just enough liquid soap or dishwashing detergent to insure the droplets spread out and cover the leaf instead of beading up and running off. A squirt of this will instantly kill the mildew. However, the disease usually occurs when conditions are unfavorable to the plant, and after you’ve sprayed it away, PMD will usually appear again in a few days. If PMD occurs during a short spell of unseasonably unfavorable weather, stopping it for a few days can save the day.

I suggest mixing kelp tea and fish emulsion into the spray tank with the baking soda/soap solution.Why not.