NO man moved. The boss canvasman pushed the door shut quickly. Cameron and Finnerty, momentarily disturbed, resumed talking. The card players were soon quarreling again over the game.

“I took it with my ace,” insisted one.

“You did like hell, you mean you took an ace from underneath,” scowled the other.

Silver Moon Dugan joined Cameron and Finnerty.

Gorilla Haley rose, his jaws swollen with tobacco juice. He rushed to the door and swung it open.

“God Almighty, Gorilla, it’s wet enough outside. Do you wanta flood the state?” the Ghost asked.

“Shut your trap,” flared Gorilla, shambling back to his place.

My worn brain would not allow me to sleep.

I thought once of crawling over the train to the horse car. One of the horses had been ill that day and I knew that Jock would travel with him. It suddenly dawned on me that the car had no end exits, out of which I might have muscled myself onto the roof of the next car.

Blackie, still holding his pipe, rose indifferently and walked to the end of the car. He stood still for a moment, legs spread apart, head down. In another second he laid his pipe on a wet piece of canvas, then turned, facing us.

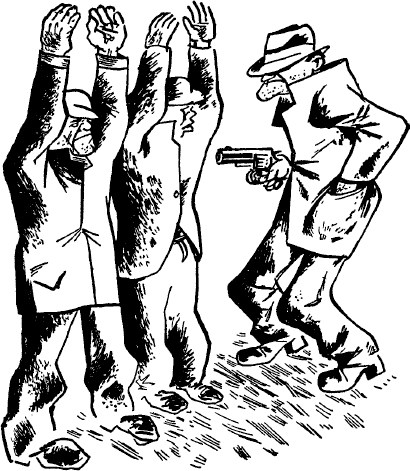

“Everybody stand up!” He whipped out the words sharply. In his extended right hand a blue steel gun. It looked to me as long as a railroad tie.

We all rose like soldiers standing at attention. Cameron was the most obedient. Silver Moon hesitated.

“Work fast, you lame bastard. I just want an excuse to send you to hell.” He took one step forward. “I’ll put a hole through you so big you can pound a stake in it.” Silver Moon’s lip curled, as he hesitated about putting up his hands.

For a paralyzing second I thought Blackie would shoot. He held the gun on a level with Dugan’s heart and moved nearer. I closed my eyes as if to shut out the noise of the explosion. Then Blackie’s voice went on. “What a dirty bunch of sons of bitches you all are.” Then, looking straight at Dugan, Cameron and Finnerty—“Throw your gats down. And let me hear them fall hard. Come on.” Finnerty and Dugan threw revolvers on the floor.

“Now throw your money down—fast—every God damn one of you.” Pocketbooks followed the guns. I threw a twenty-five cent piece.

Blackie half-grinned as it lit near a revolver.

He turned to me. “Open that door, kid.” Obedient at once, I slid the door backward its full length of six feet.

The noise of the rushing train increased. The rain swished across the car.

“Now everybody turn around. Walk to the door—and jump. The guy that turns gets a bullet through his dome.”

Cameron looked at Blackie appealingly. Blackie laughed.

“You crooked old hypocrite, you can’t talk your way outta this.” He lunged forward with the gun and shouted, “JUMP!”

Being second to no man in the art of catching a flying train, I jumped swiftly and with supreme confidence. The rest of the men followed me.

Before I could gain my balance on the soggy ground, a car had passed. There were two more to come. I knew every iron ladder and every portion of the train by heart. I could see the forms of the other men, some stretched out, others scrambling to their feet on the ground. I heard an unearthly screech. A gun went off.

My brain, long trained in hobo lore, functioned fast. I sized up the ground to make sure of my footing and looked ahead to make sure I would crash into no bridge while running swiftly with the train.

When one more car whirled by me, I started running.

If I missed the end of the last car I at least would not be thrown under the train. Running full speed, my brain racing with my feet, I knew that to grab was one thing, to grab and not to miss was another, and to cling like frozen death once my hands went round the iron rung of the ladder. I knew that I must race with the train, else if I grabbed it while I stood still, my arms might be jerked out of their sockets.

My cap was gone. The rain slashed across my face. When about to grab, my right foot slipped, and I was thrown off my balance for a second.

With muscles suddenly taut, then loosened like a springing tiger’s, I sprang upward. My hands clung to the iron rung. My body was jerked toward the train. Thinking quickly, I buried my jaw in my left shoulder, pugilist fashion. It saved me from being knocked out by the impact of my jaw with the side of the car. I finally got my left foot on the bottom of the ladder, my right leg dangling.

The car passed the group who had been redlighted with me. A man grabbed at my right foot. I kicked desperately, and felt for an instant my foot against the flesh of his face. My arms ached as though they were being severed from my shoulders with a razor blade. A numbness crept over me. My brain throbbed in unison with my heart. Drilled in primitive endurance of the road for four long years, I was to face the supreme test.

I had no love for the red-lighted men. Rather, I admired Blackie more. Neither did I blame him for red-lighting me. A man had once trusted another in my world. He was betrayed.

I had the young road kid’s terrible aversion against walking the track for any man. My law was—to stay with the train, to allow no man to “ditch” me.

When the numbness left me I crawled up the ladder. Blinded by the rain, my hair plastered to my head in spite of the wind that roared round the train, I lay, face downward, and clawed with tired hands at the roof of the smooth wet car.

Sometime afterward, whether a minute or an hour, I do not know, I tried to rise. My arms bent. I lay flat again.

My mania had been to tell Jock. It suddenly dawned on me to tell anybody I saw. But how could I see anyone while the train lurched through the wind-driven and rain-washed night?

I cried in the intensity of emotion. Pulling myself together, I dragged my body to the end of the first car, about sixty feet. Reaching there, I had not the strength to muscle my body to the next car. After a seemingly endless exertion I pulled myself across the three-foot chasm between the two cars. Beneath me the wheels clicked with fierce revolutions on the rails. The wind blew the rain in heavy gusts through the chasm.

With the aid of the chain which ran from the wheel at the top of the car to the brake beneath, I worked my body around to the ladder, and crawled laboriously to the top of the second car. My muscles throbbed with pain at the armpits. I wondered if I had dislocated my arms. I tried to crawl on my hands and knees, and gave it up. Finally I succeeded in dragging myself across the second car. My heart pounded as though it would jump from my breast.

I leaned out from my position between the cars. The light still gleamed in the open door of the car from which we had been red-lighted.

Blackie was standing in the doorway. His shadow was thrown far across the ground. The running train gave it a weird dancing effect. It pumped over the rough earth and cut through telegraph poles and fences as the rain splashed upon it.

The engine whistled loud and long. My heart jumped with glee. It was going to stop. Suddenly the train gained momentum and the engine whistled twice. This meant: straight through. We passed a few red and green lights, and later some that were yellowish white.

The whistle shrieked again, a low moaning dismal effort like a whistle being blown under water. I sensed a long run for the train. The fireman’s hand lay heavily on the bell rope. It became light as day each time he opened the fire-box to shovel in coal.

The rain still slashed downward with blinding fury. In spite of everything my eyes became heavy. Knowing the folly of going to sleep and falling between the cars, I opened my coat and held my body close to the iron rod which held the brake. I then buttoned the coat around it. While being forced to stand as rigid as one in a straight jacket, it would nevertheless save me from being dashed under the wheels.

After many wet miles the train slowed at the edge of a railroad yard. Lights from engines blended with white steam and made the yards light as early day.

I looked across the yards and saw Blackie making for the open road.

We gained speed for a few minutes and then ran slower, at last coming to a stop in the yards.

I hurried to the horse car and found Jock. He was sitting on some straw near Jerry, the sick horse. I gasped out the story of the red-lighting to him.

Jock said without energy, “It was a tough break for you, kid,” and shrugged his shoulders. “I’ll tell the Baby Buzzard.” He frowned. “We’ll have to go back after them, I guess.”

He studied for another moment. “It would be a great stunt to let ’em walk in. They deserve it. But no. I guess it’s best for you to come and tell the Baby Buzzard. We’ll be all finished in a week and you’d lose your wages if you ducked now and didn’t tell.”

“Yeah, Jock, you’re right,” I said. And then, “I saw Blackie beatin’ it across the yards about a mile back.”

“Well,” exclaimed Jock, “say nothin’ about it, kid. A guy that kin pull a stunt like that deserves to go free. I don’t think he meant you no harm. He had to red-light you, too.”

“Gosh! I wonder what he’d think if he knew I made the train again.”

“He wouldn’t be surprised. He’d have made it if you’d of red-lighted him. He’s just a hell of a guy, that’s all.”

Jock put on his soft grease-stained hat. “We’d better go an’ tell the Baby Buzzard together, kid, but don’t mention seein’ Blackie. Let him make his getaway. I wouldn’t turn a dog over to the law.”

“All right, Jock,” I muttered, and followed him out of the car.