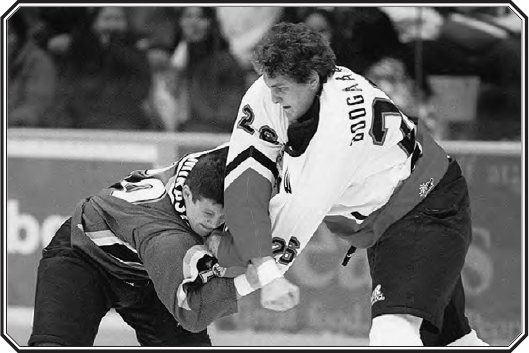

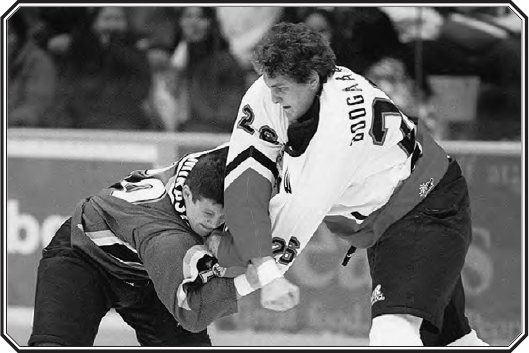

Derek fights for the Prince George Cougars.

PRINCE GEORGE, BRITISH COLUMBIA, was a mill town. Spreading mostly west from the confluence of the Fraser and Nechako Rivers, it sprawled over a pine-covered landscape shaped like a rumpled blanket. It began as a fur-trading post two centuries ago and became a vital stop on the way to other places—the Yukon or the coast or the latest gold rush. It was connected to the national railroad in the early 1900s, and by the middle of the 20th century its lumber business was booming. Paper mills followed.

By the time Derek arrived in a trade, Prince George was a photogenic city of 70,000 people, seemingly quarantined from the country’s major population centers. But the Western Hockey League moved the Victoria Cougars to Prince George in 1994, attracted by the promise of a 6,000-seat arena, called the Multiplex, that opened in 1995.

Derek said goodbye to his dad, his mom, his sister and brothers, a family breaking apart. When he stepped off the plane and onto the tarmac at the airport in Prince George in late October 1999, he was 17 and far from home for the first time.

A man wearing a black Prince George Cougars jacket greeted him. It was Ed Dempsey, the team’s head coach. He drove Derek the 20 minutes through the curvy, tree-lined roads from the airport into town.

“I wasn’t feeling too good because I wasn’t used to the trees and the hills,” Derek wrote years later. “I was always used to the flat feilds [sic] of SK.”

He had to get used to it. WHL teams traveled by bus, and franchises were flung as far as 1,000 miles apart. Prince George was about nine hours west of Edmonton and 10 hours north of Vancouver. No place on the schedule was more remote. The nearest road game was in Kamloops, a six-hour drive.

A few times a season, the Cougars embarked on multi-game road trips that lasted a week or more, swinging as far south as Portland, Oregon, and as far east as Brandon, Manitoba. It was not unusual for the team bus to roll back into Prince George in broad daylight, 12 hours or more after playing a game far away.

The bus traveled about 40,000 miles each winter. While Derek was in Prince George, the Cougars replaced a three-year-old bus that had been purchased for $400,000 with a new one costing $530,000. The buses were specially designed with 12 bunks in the back and reclining seats in the front. The veteran players, ranked by games played, got to sleep in bunks on long trips. Players like Derek, when he first arrived, were relegated to sleeping while sitting.

The buses often drove through the middle of the night. To the east, the roads were often icy and windswept as they crossed great, dark prairies. In the west, many roads curled around and over snow-covered mountains. Tragedy was just one impassable sheet of ice away, and junior hockey was haunted by the memory and worry of fatal accidents.

The Pats had traded Derek to Prince George for a 17-year-old forward named Jonathan Parker. Two years earlier, Parker had been the fifth-overall choice in the WHL Bantam Draft, a swift prospect from Winnipeg expected to be a high scorer for Prince George. In his first season, Parker scored only four goals. Derek, by contrast, had not been among the 195 boys chosen in that same bantam draft, just an invitee to training camp. If nothing else, their trade was a stark reminder of the fickleness of potential and the short amount of time the boys were given to realize it.

The Cougars were a middling team with a fervent following and what might seem a geographic disadvantage. But teams had to travel all the way to Prince George to play, too, and the Cougars were always a tough opponent at home. They wanted to get tougher. The season before Derek arrived, Prince George had the fewest fights of any team in the 18-team WHL—84 in 72 games. Regina, which had signed Derek but demoted him in favor of other enforcers, led the league with 164.

It was a strange contradiction in a place like Prince George.

“Prince George is not a place where you’re going to get a majority to vote on getting hockey to stop the fighting,” said Jim Swanson, the sports editor of the Prince George Citizen for 14 years. “It’s not going to happen. It’s not a rough town, but it’s an honest town, and it’s a town that likes its hard-nosed players.”

Derek’s first meeting was with the equipment manager. Nothing fit. A ring of cloth was sewn to the bottom of the largest jersey to make it longer. Two smaller rings were added to the cuffs to lengthen Derek’s sleeves. Larger shin pads and hockey pants were ordered.

Derek stood out from the beginning. At his first practice, less than 24 hours after arriving from Regina, coaches were pleased with his loping skating stride. His skills were better than they imagined.

Reporters gawked at his height. The newspaper featured Derek in a Halloween-inspired layout, introducing him as “The Boogeyman.”

The Cougars wanted muscle. They wanted someone to get fans excited. Derek’s confidence soared.

After that first practice, Derek was called into the office of general manager Daryl Lubiniecki.

“If you win a few fights in this town,” Lubiniecki told Derek, “you could run for mayor.”

THE FIRST PUNCH that 17-year-old Derek threw for the Cougars came on November 3, 1999. It was an overhand right that struck Eric Godard of the Lethbridge Hurricanes in the jaw.

There were 5,552 fans in the arena that night. It was late in the third period. A tight game had been broken open with two quick goals, giving Prince George a 4–1 lead. So the Lethbridge coach sent Godard onto the ice. Godard was 19, stood six foot four, and weighed 215 pounds. He had been in 15 fights in the season’s first 15 games, on his way to leading the Western Hockey League in fights and penalty minutes that season.

Dempsey, the Prince George coach, responded by tapping Derek’s shoulder. Fans cheered as the boys began the familiar ritual. Derek landed the first punch. Godard hit back with a couple of quick jabs to the face, and Derek moved in closer. The boys clutched each other by the jerseys and got their arms tangled, as if caught in the same straitjacket. They scooted one another around the ice. Three officials circled and watched, casually tossing obstacles out of the way—sticks, helmets, and gloves that the boys had dropped to the ice before the fight.

The duel passed in front of the Prince George bench, then the Lethbridge one. Teammates of both boys watched the fight with expressionless faces. But the fans wanted to see their new enforcer take down one of the league’s top fighters. They stood.

Godard was able to free himself-just enough to hit Derek with a few short punches. After a minute of stand-up wrestling and fighting, the officials stepped between the exhausted boys and pulled them apart.

Both boys, given the requisite five-minute matching penalties, headed to the dressing rooms because there were only 72 seconds left in the game. But it was not the end of the fighting. With two seconds remaining, six players—three from each side—fought, too. Such was the WHL, where teenaged boxing matches were a routine part of the hockey entertainment.

For Derek, it was not a memorable debut. It blended into what became a miserable season.

“I don’t remember my first fight in P.G. actually,” he later wrote. “But they never turned out good for me. I was getting beat up a lot. My confidence was shot to shit. I was fighting with the coaches, and I would hear the snickers from the guys that I was a pussy and I didn’t know how to fight. It was a very long year for me. I struggled with everything it seemed like. No matter what I did.”

As much as anything, he was homesick. Letting Derek move 1,000 miles away was the hardest thing the Boogaards did. Joanne, especially, could not fathom sending him alone into this strange, unknown world to play a game in which he had so little future. The risks seemed to far outweigh the rewards. And Derek had been handed over to another family, strangers, at what might be the most trying point in his life.

In the tumultuous world of junior hockey, billet families were meant to provide stability—a home away from home, a sanctuary from the pressures and anxieties of playing top-level hockey, going to new schools, and simply growing up. Each team cultivated a list of trusted billets. Some were couples with no children, or couples whose children had grown and moved on. Others were large families who welcomed an older-brother figure, or two or three, into their lives for most of the school year. The families received game tickets and a monthly stipend of a few hundred dollars to cover the extra groceries and the cost of time and gas ferrying the boys to practices and games.

Benefits were largely intangible—an inside relationship with the local team (and the prestige that came with it), plus the satisfaction of steering boys through a time in life that can be difficult enough without the unique pressures of junior hockey. The costs were mostly intangible, too. There were meals to make, clothes to wash, school assignments to monitor. For top-level hockey players in their late teens, the problems magnified. There were concerns over curfews, drinking, and girls.

During Derek’s second season with the Cougars, an extensive story by Swanson in the Prince George Citizen highlighted Derek’s difficulties—the marital problems of his parents, the teasing of teammates, the carousel of four billet families that he rotated through in his first year.

“Mr. Swanson has no right bringing these boys’ personal lives into the attention of the public eye,” one woman wrote in a letter to the editor published by the newspaper. “These fellows are continually looked at under a microscope by the Cougars administration, agents, scouts, and other hockey officials. These teenagers are a long way from their real homes. We billet families do the best we can to pick up the pieces when our boys come home from a bad game. We don’t always know what to say or do, but a hearty attempt is made to get them to grin at least once before they go to sleep.”

There were countless reasons why a relationship between the player and his billet family did not work. They ranged from simple personality clashes to religious differences to sexual relationships that developed between players and family members, including the billet mothers.

Derek usually found billet families unbearably constricting. In turn, they found him unusually aloof. He had a habit of unintentional discourtesies, ranging from quiet brooding to post-curfew calls for a ride home. His shyness could be construed by strangers as rudeness. Struggles at school built pressure on billet families, and Derek’s size and style of play only fostered stereotypes of the doltish goon. He was not part of the clique of popular hockey players with whom families wanted to associate themselves. Most were willing to pass him along to another family.

Gone were the comforts of home, far removed by time and distance. By the time Derek had been traded from Regina to Prince George, the Cougars had already taken a road swing through Saskatchewan. The Cougars did not return until mid-February. For the first time, when Derek scanned the crowd for familiar faces, he did not see any. The distance to Prince George made it a difficult and expensive place for his family to visit. Even talking to his parents was difficult, in the days before Skype and cell-phone texting, Facebook and constant e-mail access.

But Derek’s parents would listen to radio broadcasts streamed live through their computers. Sometimes, they would call the station and ask to be placed on hold so that they could listen to the Cougars’ games. Derek did not play many minutes, and his arrival on the ice often prefaced a fight. His parents would hear the blow-by-blow of the excited play-by-play announcer—the gloves coming off, the boys swinging their fists, the groans and cheers of the crowd. Then they would hear that Derek had gone to the penalty box or, sometimes, to the dressing room. And that might be the last they heard until the phone rang hours later.

Derek fights for the Prince George Cougars.

“Mom, I’m okay,” Derek would say. “What did it sound like?”

TO APPEASE PARENTS, the Western Hockey League billed itself as a place where education was a priority. It touted a program in which each season spent in the league earned a full-year college scholarship, covering tuition, books, and fees. Dozens of players took advantage every year, and Canadian college teams were filled with former WHL players whose professional prospects had dimmed.

But for those with no college ambitions, attending high school was little more than an annoyance, a daily obstacle on the way to afternoon practice. The older boys, aged 19 and 20, were usually the stars of the team, and they had finished high school or were too old to be required to attend. The younger boys simply needed to stay enrolled to be eligible to play. The only educational expectation the Cougars placed on their players was to maintain grades in line with those they had when they arrived.

Derek played three-plus seasons in the WHL, and left at age 20 without completing the 10th grade. Once he was too old to be required to attend high school—but was more than welcome to continue playing junior hockey—Derek called home to say that he was taking a law class at a community college. His parents were excited. When asked a few weeks later how the class was going, Derek hesitantly admitted that he had dropped the class, trading it for one that taught country-and-western line dancing. A teammate was taking the course, Derek said, and it was filled with lots of cute girls.

Most players were not from Prince George, so they had few friends at Prince George Secondary School beyond their own teammates. The hockey team was its own clique, a group of ever-changing outsiders made momentarily famous by their spot on the team. They were, by turns, both revered and reviled, and sometimes those feelings ebbed with wins and losses.

Most boys at the major-junior level had been the best players on their team for many years, stars at every level. Not Derek. He was an unproven entity, prized for his size but not his talent. He was shy, and could sometimes make people laugh with his quirky sense of humor, but those were not traits that endeared testosterone-filled teenagers to one another. To teammates, Derek was a one-dimensional player, brought in to perform a task he was failing to do well.

In practice, coaches chided him for botching drills and worried that he would accidentally injure star players with a clumsy collision. One older teammate, in particular, routinely threatened to beat up Derek.

He instead found friends in some of the fringes of high-school culture, not unlike the skateboarders and snowboarders Derek had come to know in Melfort.

One of Derek’s best friends was Eric Hoarau, who had moved with his family from Nairobi at the age of seven. Eric was black, five foot seven, and did not play hockey, and his father ran an auto-repair shop on the edge of downtown called Simba Motors. Somehow, he was assigned to sit behind Derek, a foot taller, in English class. Derek spent hours at the shop and was a frequent guest at the Hoarau house. He peppered the family with questions about where they came from, why they moved to Canada, how they ended up in Prince George.

Derek had a natural curiosity about others, and about their cultures, a healthy appetite to learn more that rarely translated to his schoolwork. He didn’t find his life all that interesting, and most hockey players came from a similar background. Strangers from different cultures, with stories Derek had never heard before, were far more intriguing to him. He asked more questions than he answered, mostly out of inquisitiveness, partly to deflect attention.

Still, like most of his teammates, Derek drank, at school parties outside of town and, eventually, at bars in Prince George. Drinking was a long-standing rite of passage in junior hockey. The drinking age was 19, which meant about half of the roster was of legal age. But bars were lax, even for the underaged, especially when it came to Cougars players, who carried an air of celebrity.

“There were no drugs, but there was booze,” said Lubiniecki, the veteran general manager. “I used to have a standard in the Western Hockey League: My rule will be that if a kid is worse than I was when I was when I grew up, then he’s out of here. And I never found a kid as bad as I was.”

While in Prince George, Derek also became introduced to another enduring staple of junior hockey: the puck bunny.

It was a term, used somewhat derisively and often abbreviated to “pucks,” for the young women who hung around the team hoping to attract the affection of a player. They were the sirens of junior hockey. They scouted from the stands, mingled near the locker rooms, and found their way to the bars where players congregated. Most relationships were as fleeting as a winter storm, but the NHL is filled with players married to pucks.

Derek had never had a girlfriend. His lifelong shyness was magnified around girls. He could recite Eddie Murphy comedy routines in front of close friends, but he was painfully reticent around girls. But they were noticing him.

Derek was miserable for much of his time in Prince George. He did not like the coach, Ed Dempsey, for the same reason he struggled with so many authority figures. Derek felt untrusted and underestimated. He did not like the assistant coach, Dallas Thompson, who was also in charge of coordinating the school and billet programs for the Cougars. Thompson had plenty of issues with Derek away from the ice.

“He was a boy in a man’s body,” Thompson said of Derek. “Everything was in a hurry. He knew what he wanted to do: he wanted to play in the NHL. A lot of things, like school and growing up, got accelerated a bit, and I think it overwhelmed him at times.”

THE COUGARS WERE a good team that season, on their way to reaching the league semifinals in the playoffs. And they were popular. Of the 18 teams in the Western Hockey League, Prince George was fourth in attendance, averaging 5,801 fans per home game, trailing only teams in the larger cities of Spokane, Portland, and Calgary.

Six players from the 1999–2000 Prince George team ultimately reached the National Hockey League, at least for a few games. It was hard to imagine that Derek would be one of them. Twenty-seven players scored points for the Cougars, but Derek had no goals and no assists in 33 games. He led the Cougars in fights, with 16 (plus three with Regina before the trade), but the team had plenty of others who were willing to do the dirty work, too. In all, the Cougars had 107 game-stopping fights, a big increase from the season before, and 21 players engaged in at least one.

The users of one web site determined Derek’s fighting record to be 6–9–1, with three bouts not judged. One victory came three nights after Derek’s Prince George debut brawl with Eric Godard. During a game with four fights, Derek drilled a player from the Kamloops Blazers named Jason Bone with two hard rights, knocking the boy to his knees and spilling blood on the ice.

At home in November against Kelowna, Derek was matched again with Mitch Fritz, with his Donkey Kong punches and finger-wagging bravado. In an uncommonly short bout, Derek lunged with a right hand that missed, and Fritz responded with a flurry of right hands that tagged Derek several times in the face. Derek fell to the ice. Fritz headed to the penalty box. Derek left immediately for the dressing room—a humbled enforcer’s sign of injury and defeat.

Fritz beat Derek again in January, surprising him with a quick barrage that knocked Derek down. In February, prompted by Derek’s beating of one of Fritz’s teammates earlier in the game, they met again during the first of a seven-game, 12-day road trip east. By now, Derek was well schooled in the choreography of hockey fights. Waiting for a face-off near one goal, Fritz asked Derek if he wanted to fight. Derek nodded casually. Once the puck dropped, the two swerved their way to the middle of the rink, shedding equipment and building anticipation.

The crowd rose as the boys slid toward center ice, the circus’s center ring. Fritz skated toward Derek and struck him with his right fist as Derek moved backward. The blow dropped Derek to the ice, a signal for officials to intervene. But Derek quickly jumped to his feet. With an official draped on each boy, each player bigger than the men trying to contain them, Derek fired a right hand that knocked Fritz off balance.

Fritz, angered, tried to duck and wrangle out of the official’s hold, but could not get close enough to continue the fight. The boys shouted at one another, like boxers held back by their handlers. The Kelowna crowd cheered.

The Cougars headed to Swift Current. Mat Sommerfeld, Derek’s old nemesis, cracked Derek’s chin with a series of left-hand jabs. The boys fell to their knees and sprung up. Sommerfeld hit Derek with a right, knocking him to his knees momentarily again. Sommerfeld landed more punches until Derek wrestled his opponent to the ice in a pile.

Derek called Len late that night. In the pile, he said, Sommerfeld bit him on the hand. In the hours since, it had swelled grotesquely and kept Derek awake with pain.

Len drove two hours from Regina to Swift Current and took Derek to the hospital in the middle of the night. Doctors diagnosed an infection and gave Derek shots. Len, frustrated at being called to intervene in his son’s care, began to wonder whether teams had the best interests of the boys in mind.

“Then came the night that was good and kind of a bad thing for me,” Derek wrote.

It was March 3, 2000. The Cougars were home, in front of another sold-out crowd of 5,970, playing the Tri-City Americans. In the second period, Derek faced a 19-year-old named Mike Lee, a six-foot, 230-pounder from Alaska.

The fight ended almost as soon as it started. Lee smacked Derek with a punch. The boys were escorted to the penalty box. Derek, without revealing that he was hurt, sat trying to coordinate his jaw and get it back into place.

“I couldn’t close my mouth,” Derek wrote later. “My teeth wouldn’t line up.”

His jaw was broken. X-rays at the hospital proved it, and doctors said the jaw required surgical repair. Derek awoke to find his mouth wired shut. Doctors placed him on a liquid diet. His season over, the Cougars sent him home to Regina.

Derek had been missing teeth from previous fights and a stick he took to the mouth. Now, between the wires, he had a hole where he could insert a straw during the six weeks his jaw was wired shut. The hole in his teeth, he found, was the perfect size for French fries.

DEREK TURNED 18 in June, and he privately wondered if he might get selected in that month’s National Hockey League draft. The notion was ridiculous enough that he kept it to himself.

“I was still kinda hoping that somebody would take a chance on me,” he wrote as an adult.

No one did. But several of Derek’s teammates and opponents were drafted. Sommerfeld, Derek’s rival, was selected in the eighth round, 253rd overall, by the Florida Panthers. (He played two more seasons of junior hockey before leaving the game with complications from concussions, and became a farmer near his hometown.)

The broken jaw and wired mouth gave Derek plenty of time to ponder where he wanted his life to go. He was not going to graduate from high school. He likely was headed toward a career of labor, working the oil fields or in a manufacturing plant somewhere, and if he did not play hockey, that future would start sooner rather than later. His family was little solace.

The house in Regina was remodeled and ready, and the Boogaards moved in at about the time Derek completed his first season in Prince George. A month later, the day after Mother’s Day, Joanne returned home to find that Len had moved out. Their marriage, approaching its 20th anniversary, was headed for divorce.

Derek escaped by burying himself in his hockey pursuits. Another season like the last, and opportunity would expire. He spent much of the summer at a gym called Level 10 Fitness, with a trainer named Dan Farthing. Derek now had a leanness that was evident everywhere from his thinning cheeks to his broadening chest and flattening stomach.

He boxed. He ran. He spent hours with his brother Ryan, reviewing videos of his fights and scouting his opponents. Derek never felt more prepared and more anxious to start a season. Yet he nearly quit before it began.

Derek wanted to choose his billet family, but the Cougars were not going to let Derek dictate his living arrangements. Derek had not been unhappy with his primary first-year billets, but he had made a connection with another family. Mike and Caren Tobin owned a jewelry store in a well-tended strip mall in Prince George, and they lived in a neatly landscaped, remodeled two-story house on a quiet street outside of town. They had toddler-aged twin daughters. They had been billets for a few years and were hosting one of Derek’s teammates. The boy told the Tobins about Derek.

“Mike, you should see this guy,” the boy said. “He’s so big, he won’t even fit in my car.”

The Tobins said to invite him over.

“Here’s this giant, pimple-faced galoot walking in the door,” Mike Tobin recalled. “And he was shy. Oh, my God, was he shy.”

Derek sat quietly on the couch, watching television. Caren asked if he wanted something to drink. No, thank you, Derek mumbled. Something to eat? No, thank you, he said.

“He kept to himself,” Caren Tobin said. “But once he became your friend, he would always be there for you.”

Mike Tobin had had a difficult childhood and quit school after the eighth grade. A family connection led to an apprenticeship as a goldsmith, which led to his own jewelry business, built into a success. Mike had just purchased a Porsche, and the Tobin residence might have been the nicest home Derek had ever been inside.

Derek soon fell for Caren’s roast beef, and Mike was soon taking him to movies and sparking an interest in high-performance cars. Derek opened up. At a time when Derek’s own family was breaking apart, the Tobins offered reliable comfort. Mike became the sort of big-brother figure that Derek had not had—part friend, part role model.

It was part of a lifelong pattern for Derek. He usually painted adults, particularly those with some authority over his life, in one of two stark shades. Either you were for Derek or against him; there was little in between. He did not like most of his teachers, who put demands on him that he never fully understood. He adored about half of the coaches he had and detested the others. Whether authority figures fell on one side or the other was usually a reflection of the amount of faith they showed in Derek—or, conversely, the amount of pressure and discipline they exerted on him.

More than anyone, Mike Tobin boosted Derek’s confidence, listened to his problems, and offered a worry-free place to unwind. There was no harping about hockey or school or anything else. A neighbor of the Tobins worked at the high school. She warned them that Derek was not worth the trouble—a bad student, a bad kid. The Tobins never saw it.

There were several hockey players living with billets in the neighborhood, and the Tobin home became a hub. When the boys gathered, either to watch television on the big screen in the basement or to have a big dinner, the Tobins usually told them to bring Derek.

But the Cougars denied Derek’s request to live with the Tobins. When Derek arrived at the airport for his second season in Prince George, he was driven to the home of another family. Nice people, Derek recalled, but they were smokers, and Derek wanted no part of that. He sulked. He moved through another billet family before settling with still another. Derek liked them, but the husband was a statistician for the Cougars. Derek felt as if he was being monitored by the team.

His frustration boiled over following a run-in with Thompson, the assistant coach and the one in charge of billeting. Thompson, persistently frustrated by Derek on and off the ice, was not happy with the way Derek casually greeted Thompson’s wife, the daughter of the owner. Thompson berated Derek for the disrespectful slight.

That was it. Derek decided to quit. He bought a plane ticket to Regina and called his father to say he was coming home. He went into the dressing room and told teammates he was leaving. A couple of them tried to talk him out of it.

Derek went to tell Mike Tobin.

“Don’t be a quitter,” Tobin said. “That’s what they want you to do.”

Tobin had seen firsthand how players were treated as disposable goods. He had come home from work several times over the years to find boys in tears, packing their bags, told they had been shipped somewhere else.

Derek said he would demand a trade. Tobin laughed. He knew Derek had no standing to make demands. He didn’t even have enough standing to request billets. They would dismiss him as a cancer and sit him. They’ve got you, Derek, Tobin told him. You can sulk or prove them wrong.

Derek met with the Prince George coaches the next day. As if his mouth were still wired shut, he mostly stayed quiet, swallowing his frustration. He never used the plane ticket.

DEREK FOUGHT 31 TIMES in 2000–01, more than any other season of his life. The first was on September 27, at home against the Kootenay Ice. He beat up Trevor Johnson, who was nine inches shorter and more than 50 pounds lighter than Derek, who weighed himself daily and usually hovered between 240 and 250 pounds.

On October 8 against Regina, Derek and David Kaczowka fought twice, giving Derek a chance to show his former team what it had traded away a year before. Kaczowka was on his way to a league-high 50 fights that season. But Derek stood strong, edging him in the first fight with a quick rash of punches thrown despite having his jersey pulled over his head. The second fight, part of a five-on-five line brawl, was quickly strangled by officials.

The next night, Prince George hosted the Tri-City Americans. Derek was nervous. It was time to repay Mike Lee, the fighter who had broken Derek’s jaw seven months earlier. The coaches put their pugilists out on the ice early in the first period.

Derek sidled up to Lee. “Wanna go?” he asked.

Derek wasted little time in delivering several big blows, exacting his revenge.

Later in the game, the Americans sent another player out to fight Derek. He dispatched him, too.

The Boogeyman’s payback tour was in full force. On October 11, Prince George played at Swift Current. Midway through the second period, Derek found himself on the ice with Sommerfeld, his nemesis, recently drafted. Derek surprised Sommerfeld with a left hand, then followed with a right. Another right hand smashed into Sommerfeld’s face, bloodying his nose.

Suddenly, during home games in Prince George, the Multiplex would fill with the sound of Derek’s name, a call and answer that echoed through the sold-out arena. One side shouted, “Boo!” The other responded, “Gaard!”

The coaches found that Derek, finally, could do what the best fighters could do: strike fear into opposing teams, change the way they treated the star players, shift the momentum with a crowd-pleasing beating. Other WHL teams began inquiring about trades for him.

It was all about the fighting. Derek didn’t register a point until his 54th WHL game, an assist again Kamloops.

“It’s nice to have something other than penalty minutes beside my name,” Boogaard told the Prince George Citizen that night. “When I get a goal, I’ll grab the puck myself and no one will stop me.”

It happened on January 3, 2001. Derek, now playing meaningful shifts alongside top players, found a puck in the slot and jammed it through the legs of the Kamloops goalie. He never saw it go in, but the reaction of the crowd told him. A chant bounced through the arena—Boo-gey, Boo-gey, Boo-gey …

Derek wanted to be famous for the glory of goals, not the fury of his fists. Now, at 18, he dreamed of being an all-around player, someone like Bob Probert or his boyhood hero, Wendel Clark—men with scoring punch to go with their punches, respected players who could be trusted to be on the ice while the clock was ticking, not just when it stopped for a fight.

“I have to work harder, and not always look for the fights,” Derek said after he scored his first goal.

But Derek did not score again during the regular season. His reputation was cemented and his future ordained. Internet fight fans gave Derek an 18–4–4 record that season. Five other fights were not reviewed. He had 245 penalty minutes, eighth highest in the league. He was voted “toughest player” in the Western Hockey League’s Western Conference.

GAME 4 OF Prince George’s playoff series with the Portland Winter Hawks took place on April 4, 2001, at the sold-out Multiplex. Portland led the series, two games to one, and the teams headed to overtime.

And there was Derek, playing left wing in sudden-death of a game that Prince George was desperate to win, the score tied, 4–4, the seats filled with 6,000 anxious Cougars fans, Prince George coach Ed Dempsey looking for someone to be the star.

“All of a sudden, Ed said our line was up,” Derek later wrote.

Teammate Devin Wilson dumped the puck into a corner. Derek chased it down. He tried to center it to Dan Baum, but the puck bounced around before Baum was able to stab it. His shot trickled behind the Portland goalie.

“I turned around and the puck was just sitting there,” Derek recalled.

He swiped it in.

The crowd erupted.

“I don’t think I ever saw our rink, or Derek, that happy,” Thompson, then the assistant coach, said a decade later.

Teammates ambushed Derek, burying him in a pile. One rushed to grab the puck so that Derek would have the memento.

“It was an unbelievable feeling,” Derek wrote. “The guys came out of the bench and the place was going nuts. It was the best feeling I had the last 2 years.”

The giddiness of the goal trailed the Cougars out of town. The series now even, the Cougars boarded their bus for Portland, 700 miles and more than 14 hours away. But the boost that Derek provided evaporated. The Winter Hawks beat Prince George handily in Game 5, shutting them out 6–0.

The teams returned to Prince George—14 hours back north—for Game 6. Before another raucous sold-out crowd, the Cougars held a 3–1 lead midway through the second period. But the bottom dropped out in mere moments. Portland scored four unanswered goals, one of them on a power play after a Derek penalty, and the season ticked to a disappointing close.

In the final seconds, with the score 5–3, Dempsey again sent Derek onto the ice. Just as the Portland goalie bent over to pick up the puck as a souvenir, Derek barreled into him.

Portland coach Mike Williamson was incensed. He accused Dempsey of sending Derek out to try to hurt his players, and the coaches had a shouting match under the stands 30 minutes after the game.

The Western Hockey League suspended Dempsey for three games and fined him $5,000. But Derek took the brunt of the punishment. He was suspended for seven games, to be served at the start of the following season.

“It’s very unfortunate, because the talk around the league had been how much improvement Boogaard has shown recently,” WHL vice president Rick Doerksen told the Prince George Citizen. “But what he did was an unprovoked act that has no place in our league.” Derek never revealed Dempsey’s instructions to him. Part of the enforcer’s code was to quietly accept responsibility.

THE NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE Entry Draft was scheduled for two days beginning June 23, Derek’s 19th birthday. Derek again wondered if he might be selected. Joanne Boogaard thought that such hope was ridiculous. She wanted Derek to quit hockey.

In early May, 14-year-old Aaron Boogaard was chosen in the first round, 14th overall, of the WHL Bantam Draft, by the Calgary Hitmen. Aaron was already six foot one and 200 pounds, and he was a much faster, far niftier puck handler than Derek. The combination of his own abilities and his brother’s reputation made him a treasured recruit. Derek was never drafted by the WHL. He only gained notice with his size and with an out-of-character tirade in a small-town rink. Four years later, after his second year in the WHL, he was one of the better enforcers in the rough-and-tumble league, but hardly a star.

Joanne demanded that Derek get an off-season job. She had little patience for laziness. After all, Joanne had two jobs after high school, all the way until she married Len years later. Now she was a single mother of four children. She was not going to allow Derek to sit around all summer. Hockey had become a tool of procrastination. It was time to move on—if not school, then work.

Len Boogaard lived in a nearby apartment. He was in a full-fledged relationship with Jody Vail, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police member he had helped train in Melfort beginning in 1997. Joanne had tried to ensure that Jody would not be transferred to Regina when the Boogaards moved there, but Jody was transferred to a small town about 30 minutes away. The Boogaards divorced, after several years of tumultuous separations, and Len and Jody would marry a year later, in 2002.

Len trod the middle ground when it came to Derek’s hockey career. Pick what you are going to do, and do it all the way, he told his son. If you want to play hockey, prepare for the next season. If you are finished, get a job.

Derek did both. He found work at a golf course near the RCMP Depot. He hated it from the first day. He was up at 5, at work by 6, and spent eight hours on a lawn mower. After work, he went home to eat, and then to the gym.

“At the time I was so shocked and pissed that Mom thought I wasn’t going anywhere with hockey,” Derek wrote years later. “My Dad said I could move in with him, but I was pissed right off that I didn’t want to be in the same city as the family. Now I know that times were tough for Mom because of them divorceing [sic] and my dad re-marrying. It was kind of tough for me as well but in the end the constint [sic] fighting and always arguing was and is never good.”

Derek soon had enough. He abruptly left Regina and returned to Prince George. He moved in with Mike and Caren Tobin, taking the guest bedroom at the front of the house, overlooking the driveway. Unlike his own family, the Tobins did not disappoint. There was no fighting, no nagging, and no doubt. And because it was the off-season, the Cougars had no say in the living arrangement.

Derek made himself at home, fixing three poached eggs and toast for himself every morning, always cleaning his own dishes. Mike Tobin let Derek drive his black GMC Sierra Denali, with the black leather interior and the Quadrasteer system. Derek helped with yard work, but not much before finding a shady spot on a chaise longue. At the birthday party for the twin girls, Derek spent hours happily shoveling children in and out of a giant bounce house in the front yard.

Derek was at the Tobins’ when he received a call from a Minnesota Wild scout named Paul Charles. Derek felt as if he was applying for a job, and he nervously answered the questions. The thought of getting drafted suddenly consumed him.

Derek watched the start of the draft on his birthday. Atlanta chose a Russian named Ilya Kovalchuk with the first pick. With the sixth choice, Minnesota selected Mikko Koivu of Finland. With the 12th pick, Nashville chose one of Derek’s Prince George teammates, Dan Hamhuis. Seven WHL players were chosen in the first round. Another 10 were chosen in the second, and six more in the third. Derek was not among them.

Caren Tobin made dinner and a birthday cake. A couple of friends came over, and Derek blew out the candles. Then he and his friends headed to the Iron Horse bar. With Derek of legal drinking age, his friends made sure he celebrated his birthday with an overindulgence of beers and shots. He arrived back to the Tobins’ well after midnight.

In Regina early the next morning, a phone rang inside the house on Woodward Avenue. Joanne answered. A man introduced himself as Tommy Thompson, the chief scout of the Minnesota Wild. He told Joanne that the Wild had drafted her son Derek.

Joanne was confused.

“But he’s already on a team, in Prince George,” she replied.

“No, this is the National Hockey League,” Thompson said.

“The NHL?” Joanne said, incredulously. “You’ve got to be kidding.”

Moments later, a phone rang in Prince George. Caren Tobin answered. She called up to Derek’s room, but he was asleep and did not respond. She went upstairs and knocked on the door. Then she banged on it.

“Take a message,” Derek moaned.

She ordered him to the phone. She and Mike knew what was happening, and Derek came downstairs, groggy.

“Hello?” he said. “Uh-huh. Uh-huh. Yeah. Okay. Yeah. Okay. Thanks.”

He hung up, expressionless.

“Well?” Caren said.

“I got drafted by Minnesota,” Derek said. He was chosen in the seventh round, 202nd overall.

The Tobins wrapped Derek in hugs.

“I was very excited as well,” Derek wrote later. “With a huge headache.”

THE WILD HELD a four-week camp for prospects in Breezy Point, Minnesota, a few weeks later, but Derek first had to stop in Saint Paul, the team’s headquarters. In his hotel room, he found a package of forms to fill out and information to read. It explained that teams had two years to sign a player after they drafted him, a sort of tryout period as boys move through the ranks of junior and the minor leagues.

Derek walked to the Xcel Energy Center, the Wild’s downtown arena. The team had only played one season, and the arena still felt brand new. The dressing room was the biggest Derek had seen. An equipment manager fitted him for gear. For the first time, everything Derek tried on was new, as if made exclusively for him. He pulled a Wild jersey over his head. There was no need to sew an extra ring of material to the bottom, or at the ends of the sleeves. It fit perfectly.

While Derek was in Breezy Point, the Cougars, far away, openly discussed trading him. They knew that Derek would miss the first seven games of the 72-game schedule because of the suspension. He had been through several billet families and now had requested to stay with the Tobins. The Cougars were weary of handling Derek. Junior hockey was an assembly line, and replacements were ready.

“He’s got one goal, he’s drafted now, and now he probably thinks he’s going to be on the power play and on the second line,” Lubiniecki, the team’s general manager, told the Prince George Citizen.

Derek brimmed with confidence. He returned to Prince George in tremendous shape, weighing 245 pounds. His long hair had been cut short again. He was no longer an outcast, but an NHL draft pick with a future. He was wanted.

Derek’s family noticed the change. During a visit to Prince George, Len asked to speak privately to Mike Tobin.

“I just can’t believe the change in Derek,” Len said. “We went to Earls the other day, and a girl walked up to our table. Six months ago, if a girl would have walked up to our table and starting talking to him, he would have crawled under the table. I can’t believe the difference.”

Derek was gone again, back with the Wild for training camp and a rookie camp for several NHL teams in Traverse City, Michigan. During one scrimmage, Derek thought he had a player lined up for a big hit. He took several long strides and turned his shoulder to smash the opponent into the side boards. The other player ducked at the last moment.

Derek crashed through the glass, shattering it into thousands of tiny pieces. His body folded over the boards and flipped out of the rink. The arena went silent as coaches and scouts rose with worry and awe.

Derek stood and, with a sheepish grin, climbed back over the boards, onto the ice. Pebbles of broken glass encrusted his jersey. When Derek came to the rink the next day, he found a taped outline of a large player on the new pane of glass, as if it were the sidewalk of a crime scene.

Derek was with the Wild for training camp in Saint Paul during the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, D.C. Two days later, during a scrimmage, he exchanged punches with the Wild’s veteran enforcer, Matt Johnson.

Wild head coach Jacques Lemaire was not a fan of players beating up teammates. He shouted down from his seat in the stands, asking another player to break up the fight. A day later, Derek was sent, as expected, back to Prince George for the WHL season.

Derek did not want to be there, and the Cougars were not excited to have him. He sat out the first seven games because of his suspension, but other players combined to take on Derek’s role, fighting 13 times in the seven games. The Cougars had won three of their last four games when they, along with Derek, embarked on a long, eastward road trip.

At the first stop, in Red Deer, Alberta, Derek twice fought Jeff Smith, a sturdy 20-year-old enforcer from Regina. Derek looked stronger and more fearless than ever.

But he snapped the next night in Calgary. On Derek’s first shift, 80 seconds into the first period against the Hitmen, he was penalized for roughing. Later, the teams had two bloody brawls while Derek was penned in the bench. Prince George led, 5–3, early in the third period, when Derek was called for roughing again. This time, he did not quietly skate toward the penalty box. He could not be constrained.

It was unlike anything Derek’s family had seen since his rampage into the opponents’ bench as a 14-year-old in Melfort. A linesman tried to pry Derek away and escort him off the ice. Derek shoved him—a huge breach of rules and protocol. He threw his helmet toward opposing players. He flashed his middle finger to the referee.

Derek was immediately ejected from the game, and the WHL quickly suspended him indefinitely. The Cougars were furious. They had been trying to trade him.

“He’s got to get smarter,” Lubiniecki told the Prince George Citizen. “The bottom line is, right now Derek Boogaard just can’t keep it together. He’s becoming a liability from the fact that he can’t play the games because the league won’t let him. He won’t use the thought process he needs to, to keep himself in games. If anyone has tried to make this guy a responsible player, it’s our organization.”

The league ultimately handed Derek a four-game suspension, but the Cougars were finished with him. Before he could play again for Prince George, Derek was traded to the Medicine Hat Tigers. In return, Prince George received a 19-year-old third-line center named Denny Johnston and a fourth-round pick in the next year’s bantam draft.

“I painted my own picture,” Derek told the Prince George Citizen. “It was me who caused this trade to happen.”

Only Derek and his mother knew what truly had made Derek snap in Calgary. Joanne had driven from Regina to Calgary, eight hours away, because there was something she wanted to tell her son. And she did not want to do it over the phone.

Months earlier, the same week that Len had moved out, Joanne received a letter from social services. Joanne had become pregnant when she was in high school, years before she met Len, a decade before she had Derek. She had the baby, a healthy boy, and then gave him up for adoption. She’d kept it a secret, even from the birth father, a boy she barely knew. It was still a secret nearly three decades later. But the baby boy had grown into a man and had come looking for his birth mother, the way Joanne always wondered if he might. His name was Curtis Heide.

Curtis had grown up in the family of an RCMP member, too, and the coincidences did not end there. His adoptive father had been posted across Saskatchewan, just like Len. At times, they were posted in nearby detachments. The men and their families never crossed paths.

Of course, Joanne wanted to meet the son she never knew. Curtis was tall and strong, like the Boogaard kids. He was quiet and humble, too, though never much of a hockey player. He had a good job in the oil-and-gas exploration industry that fueled much of the economy in the Prairie provinces.

Joanne told her three youngest children, all of whom were supportive of the news and the addition of another family member. Then she came to Calgary to tell Derek, at a restaurant before Prince George’s game against the Hitmen.

He did not take the news well. He was devastated to know that his mother had kept a secret from him all his life. He was hurt to learn that he was not the oldest of her children. For most of his life, family was the one reliable thing that Derek had. It had collapsed like a thin facade, first through divorce, now through another kind of betrayal.

“I don’t want to know about this,” he said, pushing the photograph of his half-brother back across the table. “I don’t want to hear about this.”

Derek carried the emotion silently to that night’s game at Calgary’s Saddledome. And with his mother in the stands watching, Derek did just what he was growing accustomed to doing whenever he needed an outlet from the hurt and pain, whenever he felt someone he could trust had disappointed him.

He brought it to the ice. And he took it out on someone else.

THE FIRST TIME Derek laid eyes on his girlfriend was when he flew her to Minnesota to sneak her into the Wild’s summer camp in 2002.

Janella D’Amore. You couldn’t make up a name like that. And when she walked toward him inside the terminal of the tiny airport, Derek tried his best to play it cool. He leaned against a post and watched her walk his way. In those few heart-fluttering moments, he saw everything he hoped to see. She was petite and pretty and perky, the kind of girl Derek always liked but rarely captured, with big brown eyes and wavy brown hair. And it wasn’t just how she looked. She had come all that way just for him.

Derek was 20. He was still shy and insecure around women, a trait he never could shake, the meek alter ego behind his on-ice invincibility. But in junior hockey, many young women knew who he was, especially once he was drafted.

One such woman discovered Derek when the Medicine Hat Tigers came to Portland, Oregon, in the winter of 2001 and 2002. She talked about him with her friends, including Janella, a figure skater who worked at the ice rink. Janella had not met Derek, but she was always a willing matchmaker. To gauge Derek’s interest in her friend, Janella sent him instant messages on the computer, the era’s version of passing notes. Derek responded with a dismissive remark about the other woman.

What a jerk, Janella thought. Communication stopped.

But then, from nowhere, Derek sent an instant message to Janella a few weeks later.

“Hi,” he wrote. Oh, no, Janella thought. This guy.

She thought about not answering. But she did. And she slowly found Derek to be nothing like what she imagined. His words were self-effacing and sweet. The ogre she had conjured in her mind was surprisingly kind and gentle. Janella tried to make sense of it. She asked him why he had been so rude to her friend.

“Are you kidding me?” Derek replied. “I couldn’t stand her. That girl was a total puck bunny.”

The long-distance relationship between Derek and Janella grew for weeks, through instant messages and late-night talks. Since Janella had a job, she paid the phone bills—several hundred dollars those first months.

Janella was intrigued by Derek. Hockey players usually struck her as brash, fueled by testosterone and a sense of entitlement. They worked hard and partied hard, she found. Pretty girls were an adornment that they came to expect. Derek, though, did not talk much about hockey, and never much about himself. He wanted to know about her. He made her feel important, but he also seemed nervous. Sincere. Fragile.

Amid their phone and online conversations, Derek was headed again to the Wild’s summer camp at Breezy Point, Minnesota, held at a sprawling lakeside resort. Derek had seen other players sneak girlfriends in the year before. They hatched a plan. Derek arranged for Janella to fly to Minnesota. She agreed. She paid for it.

He had no car, but he borrowed a friend’s Jeep and waited inside the tiny airport’s terminal. She got off the plane and ducked into a bathroom to check her appearance and take a deep breath.

She saw him from a distance. He was huge. She pretended not to notice him and walked past.

“Janella,” Derek finally called out. “You didn’t recognize me?”

They laughed and hugged. He thought she was beautiful. She thought he was handsome. Derek never thought of himself that way. He would always say that Janella was too pretty for him.

He carried her bag and they walked to the car.

“Don’t drive me into the woods and chop me into little pieces,” Janella said.

Derek’s room had two single beds, but they pushed them together to make one big one. They talked and took pictures. When Derek left for practice, Janella walked around the resort, bought things for him in the gift shop, went to the bar for a drink. When he returned, they took a boat ride on the lake.

But after one workout, Derek returned with bad news. The team had found out, he said. Janella was moved to another room, and her return flight home was moved up a day. The secret tryst was over.

If Derek got in trouble from the team, Janella never heard about it.

MEDICINE HAT SITS in southeastern Alberta, about a 30-minute drive to the Saskatchewan border. A sunny prairie city of 60,000, supposedly named for the lost headdress of a Cree medicine man, Medicine Hat provided Derek a fresh start, closer to home, only a four-and-a-half-hour drive east on the Trans-Canada Highway to Regina.

But the Minnesota Wild was worried about its seventh-round draft pick. Derek had gone ballistic in Calgary and been traded to the Tigers, a team on its way to a last-place finish in the Western Hockey League’s Central Division. Derek thought he should play more, considering his breakout season in Prince George and that he had been drafted by an NHL team.

Medicine Hat coach Bob Loucks, however, had another 19-year-old enforcer, a smaller scrapper from Saskatoon named Ryan Olynyk, a holdover for the Tigers from the previous season. Derek and Olynyk fought once in Prince George, but it was not much of a bout. A few minutes after beating up one of Olynyk’s teammates, Derek had checked Olynyk hard with a clean hit. When Derek skated away, Olynyk attacked from behind. Derek drilled Olynyk with a right hand. The fight ended.

Now they were teammates, but Olynyk handled most of the fighting. He led the WHL with 41 fights that season. Derek had 16. Derek dismissed Loucks as just another coach who underestimated him.

Doris Sullivan saw it unfold from her unique vantage point as a billet mother. She and her husband, Kelly, had housed a dozen players over many years, and they had another Tigers player staying with them that season. Derek walked into their lives, trailing a teammate.

As in Prince George, Derek found a home where he’d rather stay. Unlike in Prince George, there was little argument from the team. Derek moved in with the Sullivans after Christmas. They laughed at how he had to duck through doorways and how he rested his elbow on top of the refrigerator, and how he consumed entire batches of cookies at once, before they had cooled.

It was no coincidence that the billets Derek clung to were those who wanted to spend time with Derek, and not just give him a place to live. When Derek sulked, the mood was usually tinged with disappointment, not anger. More often than not, somebody he trusted had disappointed him, or expressed disappointment in him. While Derek was adept at hiding his physical pain, he did a poor job of disguising hurt feelings. Size disguised fragility.

The Sullivans had hosted a dozen or more boys over the years, but Derek stood out—and not because of his size. He must have been burned somewhere along the line, to put up those guards at such a young age, Doris Sullivan thought.

The Sullivans found Derek to be much as the Tobins in Prince George had found him. He was quiet and unassuming, content to let the conversations lull. What they all did together—watch television, play video games, go on errands—was not the important thing. He just wanted company, to be part of something, even if it felt to others like nothing at all.

Derek considered Medicine Hat a stopover between the NHL draft and a professional career. He fought when opponents dared to fight him, and the home fans still showered him with “Boo-gey, Boo-gey” chants. He had 178 penalty minutes with Medicine Hat in 2001–02, and was suspended for a total of 14 games for various rough-play infractions. He scored once. It came in February, at Regina’s Agridome, against his original WHL team. In goal for the Pats was Josh Harding, a Regina native who would be selected by the Minnesota Wild in the second round of the NHL draft four months later.

Derek’s family was in the crowd. When Derek took the ice, he scanned the stands and found their faces. And when he scored, his mother thought, once again, that maybe he could be more than an enforcer, if only someone would give him that chance.

Why don’t you stand in front of the goal, where you have a better chance of scoring, she asked him again and again. She hated the fighting—all the blows that Derek took, but, too, all the ones he delivered with increasing ferocity and effect. She thought about the other boys’ mothers, too.

“I’m not here to score goals,” Derek told the Regina newspaper, the Leader-Post. “I’m here to regulate, to enforce; don’t let other people push around our smaller players. It’s what I do.”

A man called the Sullivan house. He introduced himself to Doris as Barry MacKenzie, recently hired as the coordinator of player development for the Wild. After a player got drafted, it was MacKenzie’s job to track his progress.

Derek was his first assignment. MacKenzie had talked to other billets that Derek had been through in Prince George and Medicine Hat, and he wanted Doris Sullivan’s opinion. She gave Derek a glowing endorsement—fun to have, polite and helpful, never a problem.

MacKenzie was surprised. Others told a different story, about an aloof young man who did not like to follow rules. Sullivan suggested that others probably had not taken the time to get to know Derek well.

MacKenzie came to Medicine Hat. Before a game, he took Derek to Earls, part of an upscale restaurant chain. Derek ordered a steak.

“The coach isn’t giving me a chance,” MacKenzie recalled Derek telling him. “I don’t think they like me here. I’m not getting enough ice time.”

MacKenzie listened attentively and kept his thoughts to himself. He watched that night’s game, and then the next day’s practice. He was not impressed by Derek’s work ethic and enthusiasm. He thought Derek was going through the motions. He invited Derek out again. This time, he took him to McDonald’s.

“With what I’ve seen in the last 24 hours,” MacKenzie told Derek, “you want to eat at Earls, but you’re going to have to get used to eating at McDonald’s.”

THAT SUMMER, about the time that Derek met Janella, the Medicine Hat Tigers made a coaching change. Bob Loucks was gone. Medicine Hat hired a 45-year-old from tiny Climax, Saskatchewan, named Willie Desjardins.

When training camp opened in 2002, the Tigers had some players, like Derek, who were born in 1982 and had already turned 20. They had other players born in late 1986, yet to turn 16. Derek was more than a foot taller than some boys, and almost twice their weight.

Derek was a team leader, by virtue of his age, size, and NHL draft status, and Desjardins liked him from the start. He was surprised that Derek could skate so well for a player his size, and he noticed he had a powerful shot. Desjardins found Derek different than many young enforcers bent on building reputations with brash talk and punkish behavior. Derek was a surprisingly meek soul. Desjardins wondered if he was nasty enough to do his job.

In November, late in a lopsided loss at Swift Current, Derek took part in a 10-player brawl. The fights began slowly, and Derek stood aside, casually talking to an opposing player as others paired off to fight. He slowly turned to another Swift Current player, Mitch Love. After a few words were exchanged, Derek shoved the six-foot Love in the chest.

The boys were soon swinging fists, and two of the four on-ice officials rushed in to break them apart. Derek shook them off and hammered Love with a few right-hand uppercuts. The officials kept tugging, and the four-person scrum slid from one face-off circle to the front of the net. Derek threw haymakers until Love and one official fell to the ice. When Derek jabbed his fallen opponent with his left fist, the other official jumped and slid off Derek’s back.

Finally, the boys were escorted to the penalty box, Derek pointing at Love, while four other players continued to fight. The crowd cheered and whistled.

Desjardins had his answer. Derek—big, gentle Derek—showed he could flip the switch. He did not have to be mean. He just had to show he could be, when it mattered.

In October, just weeks into the season, Western Hockey League teams had to rid their rosters of all but three 20-year-olds. Two boys were released. Derek stayed.

It was a strange but happy fall for Derek. He lived with the Sullivans. He had a girlfriend. He felt grown up, respected, and upwardly mobile, and it showed. A former teammate from Melfort, Brett Condy, once saw Derek in a Medicine Hat bar, dancing with a “really good-looking girl,” Condy said. “You never saw that in Melfort.”

On October 20, Medicine Hat played in Calgary, at the Saddledome. For the first and only time, Derek played against his 16-year-old brother Aaron, a first-year right wing with the Calgary Hitmen. He had been drafted 15th overall in the bantam draft 18 months earlier.

“People had the perception that he was going to be the same player as me,” Derek wrote years later.

But Aaron was a smaller, quicker version of Derek. He showed no predisposition to fighting. He would do it if asked, however, and already had, in a game about a week earlier.

“Leave Nick alone,” Joanne Boogaard told Derek before their game, calling Aaron by his middle name, as family and close friends did. “Don’t you dare go after him.”

It was Aaron who tried to goad Derek, slashing him across the legs with his stick. Derek, never one to back down in the basement in Melfort or anywhere else his brothers prodded him, would not retaliate. He would not flip the switch.

The hometown Hitmen won easily, 4–1. Medicine Hat’s lone goal was scored by Derek. He ended Calgary’s shutout bid in the game’s final minutes, poking the puck past goalie Brent Krahn. It would stand as the second and final goal in Derek’s 73-game career in Medicine Hat.

Among those who cheered from the stands were Len and Joanne. Between them sat 18-year-old Ryan and 13-year-old Krysten. Also there, next to Joanne, was Curtis Heide, Derek’s half-brother, now a married man of 30 who had recently set out to find his birth mother.

Over the past year, Curtis had come to know the rest of the family. He had come to Regina and met Ryan, Aaron, and Krysten. Everyone liked Curtis. He had introduced his wife, Gladys, and Gladys’s five-year-old son, Curtis’s stepson.

Now it was Derek’s turn. He was nervous about meeting Curtis, but not as nervous as Curtis was to meet him. When the game ended, the Boogaards and Curtis moved to the front row of the Saddledome in Calgary. Derek and Curtis met. The group posed for photographs—Derek in his Medicine Hat jersey, Aaron in his Calgary Hitmen jersey, everyone wearing a brave smile. It was hard to imagine that night, but Curtis and Derek, with little more than size and a birth mother in common, were on their way to a budding relationship.

In late November, Medicine Hat embarked on a long road trip to the American Northwest. Janella met Derek in Seattle, and then introduced him to her family before the next game in Portland. She had given him a ring on an earlier trip to Medicine Hat. The guys in the locker room teased him, unaware that she was his first serious girlfriend.

Derek’s world was upended before the road trip was over. The Tigers released him.

There was irony in the shuffle. Medicine Hat dropped Derek because it wanted to shore up its defense and had signed defenseman Ryan Stempfle to take his place.

Stempfle had been released by his team, the Saskatoon Blades, when they called up Denny Johnston from a lower level. Derek and Johnston had been traded for one another just over a year earlier.

“It came as a surprise,” Boogaard told the local newspaper. “I’m disappointed, but the team needs a defenseman and you can’t do anything about the situation.”

His Western Hockey League career was over.

The final tally: three-plus seasons, three teams, three goals.

And 670 penalty minutes, mostly from his 70 fights.