5

The Santa Fe Joins the Fray

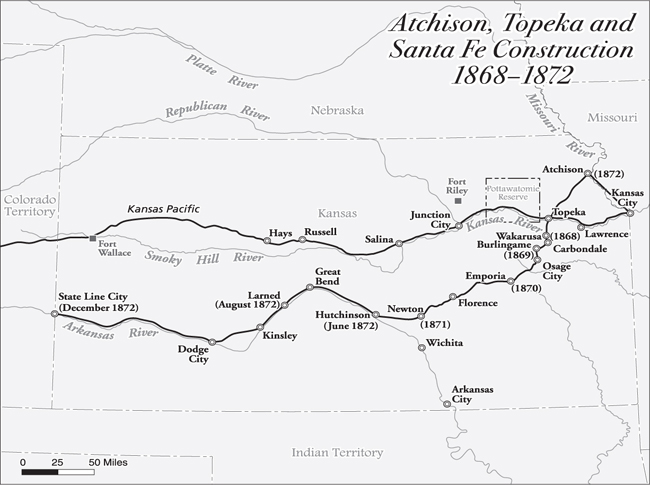

Cyrus K. Holliday’s railroad dreams did not come easily. After the incorporation of the Atchison and Topeka Railroad in September 1860, Holliday’s enterprise languished in the uncertainty of civil war. The most positive development occurred when the Republican majority in Congress—only too glad to have two more Republican senators after Kansas was granted statehood in 1861—eventually provided for substantial land grants.

On March 3, 1863, Abraham Lincoln signed a land grant bill that had been instigated by Holliday and introduced by Senator Samuel C. Pomeroy of Kansas. Designed to foster railroad construction throughout the state, it promised alternate sections of land, ten sections deep on both sides of the route—6,400 acres of land for every mile of track laid. The principal beneficiary was the Atchison and Topeka Railroad, which was to build from Atchison west to the Kansas-Colorado state line.

Lands were to be conveyed upon the completion “in a good, substantial, and workmanlike manner” of 20-mile segments of “a first-class railroad.” If previously granted homestead lands—a particular concern in the eastern part of the state—preempted a full conveyance of 6,400 acres per mile, the railroads could select other “preemption lands” within 20 miles of their route. These were to be conveyed upon completion of the entire line. In return, construction had to be completed within ten years.1

At the Chase Hotel in Topeka the following November, Atchison and Topeka shareholders elected Senator Pomeroy president of the company as a vote of thanks for his efforts in securing the land grant. They also voted to change the company’s name. Given the vast western lands to be had and Holliday’s continued exhortations that the company’s future lay in the West, the name Atchison and Topeka seemed far too limiting. Thus, the company became the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad. As the company grew, eastern capitalists would continue to call the road the Atchison, but to anyone west of the Missouri, it was simply the Santa Fe.

And to Santa Fe, the railroad was bound. But prospective land grants in the unpopulated western reaches of Kansas were one thing; immediate capital for initial construction quite another. In August 1865, the company ordered three thousand tons of iron rails at $100 per ton, but Holliday, Pomeroy, and their East Coast agents were unable to raise the required funds. The rail order was cancelled, and the next two years saw no better results.

What the railroad desperately needed was developable land closer to Topeka. The problem was that some of the most fertile and well-watered ground was on the Potawatomi Indian Reservation northwest of town. Led by Senator Pomeroy, the railroad entered into negotiations that resulted in an 1868 treaty approved by Congress whereby the railroad purchased 338,766 acres from the Potawatomi at $1 an acre with easy six-year, 6 percent terms.

The Santa Fe turned around and put this land on the market to settlers for 20 percent down and the balance in five equal installments. Some tracts were sold for as much as $16 per acre, but others went to insiders like Pomeroy and his brother-in-law at only $1 per acre. It was a rather dubious way to fund railroad construction, but the Santa Fe had its first inflow of construction capital.

Once again, Cyrus K. Holliday was the unflagging cheerleader. “The child is born and his name is ‘Success,’ ” crowed Holliday to the Kansas State Record from his fund-raising perch in New York City. “Let the Capital City rejoice. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Rail Road will be built beyond a peradventure [uncertainty]. Work will commence immediately.”

“To no one man in Kansas,” the Record went on to say, “can the praise be awarded more surely for fostering and encouraging the various railroad schemes now making every farmer in the State richer than he was, than to Col. Holliday. While others have abandoned the project as chimerical, the Col. has never faltered.”2

Holliday was definitely a cheerleader for Topeka and his railroad, but he was also never shy about boasting of his efforts in their behalf. When a local bond issue failed and momentarily derailed his development plans for Topeka, he “almost resolved that I would quit the town.” Writing to Mary, who was traveling in Europe, Holliday grumbled, “I have given the place eighteen years of my life and a great deal of money—as you well know—and without my unceasing and untiring efforts Topeka, today, would be no better than the small communities around her.”3

But when the first shovel of dirt was turned later in the fall of 1868, Atchison residents thought something terribly amiss. The grade did not start in Atchison or even lead northeast out of Topeka toward their city. Instead it ran south from Topeka toward coal deposits at Carbondale, a dozen miles away and a ready market. And when construction started in the opposite direction, it was not to reach Atchison but merely to drive pilings for a bridge across the Kansas River on the outskirts of Topeka and make a connection with the Kansas Pacific Railway.

The neophyte Santa Fe could hardly call the established Kansas Pacific its competitor—yet—and in the interim, the Kansas Pacific provided an easy route over which construction materiel from the East could reach the Santa Fe’s railhead. The 1,400-foot bridge over the Kansas River was opened to traffic on March 30, 1869, and the first Santa Fe locomotive over the new line was christened the Cyrus K. Holliday.

Compared to the smoke-belching behemoths that would one day roar over the Santa Fe line, the “Holliday” was a decidedly dainty machine. It had a pointy cowcatcher, balloon smokestack, and a 4-4-0 wheel configuration—the four drivers being five feet tall. Originally built in Cincinnati for the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad, the locomotive arrived in North Topeka via the Kansas Pacific and was soon pulling flatcars loaded with rails across the new bridge.

More locomotives and rolling stock quickly followed, including a rickety wooden coach purchased used from the Indianapolis and Cincinnati Railroad. By July 1, the Santa Fe was operational into Carbondale, and coal shipments contributed important freight revenue. Ten weeks later, another 27 miles of track was completed to Burlingame in western Osage County. The town went wild.

The Osage Chronicle boasted that “old earth slowly careened in the direction of Emporia, changing her center from the poles to Burlingame…” (Never mind that a caricature of a steam engine accompanying the story looked more like the original Tom Thumb of the Baltimore and Ohio than the Cyrus K. Holliday.) “Rival papers, please ‘toot!’ ” the Chronicle concluded.4

Now there was a little momentum behind the line. It became easier to attract eastern capital, and the grade was pushed farther southwest. Emporia took the Santa Fe’s arrival in July 1870 in stride—largely because since the prior December it had been connected to the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad (fondly called “the Katy”). But for the Santa Fe, reaching Emporia was significant. This was the first of the cattle towns it would encounter. Now both cattle and coal rolled into Topeka on the little road.

These revenues and the promise of more cattle the farther west the line built encouraged Santa Fe stockholders. But the townspeople of Atchison—still waiting for the Topeka-Atchison link to be completed—were becoming increasingly disgruntled. Their anger grew when a large order of rails arrived in St. Louis, bound not for Atchison but for the railhead at Emporia.

Atchison grumbling aside, the Santa Fe’s directors soon realized that they could no longer afford to benefit the Kansas Pacific by turning freight over to it in North Topeka. It was finally time to build its own line to Atchison. There the Santa Fe had a choice of three railroads not in direct competition with it for access to Chicago and St. Louis, including the Rock Island, and the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy. Even so, delayed by a lack of rails, the first through train between Atchison and Topeka did not operate until May 13, 1872.5

Meanwhile, survey crews had been moving rapidly west of Emporia toward Fort Dodge. The first major stop was the new town of Newton. It was a typical railhead boomtown. One day there was nothing but wide-open prairie and a few survey stakes marking the proposed right-of-way. Almost overnight, a hodgepodge of buildings sprang up.

Few locations marked the line of the frontier as heavily as the railhead. By their very nature, railhead construction camps were rough and rowdy places, populated by men who needed to blow off steam after a week of heavy work. But behind the advancing iron horse, its tracks stretched as a conduit, not only of construction men and materiel but also the rush of civilization itself: farmers, ranchers, merchants, and more.

Sometimes the railhead was a mobile mass of tents, wagons, and people inching its way across the plains. At other times, construction delays caused by lack of supplies or financing forced a pause in one location. But one thing was certain. The coming of the railroad would change the landscape forever. As one report from the Kansas plains prophesied: “Settlers are fast coming into the valley. Town lots are selling fast. The change that will take place within one year, even in this town and surrounding country, is hardly to be realized.”6

The Kansas Daily Commonwealth of Topeka noted Newton’s arrival as “an enterprising railroad town, situated on the [railroad] and the intersection of the great Texas cattle trail.” Four weeks after the first building was commenced, there were “twenty houses almost finished, with lumber on the ground for the speedy erection of many more.”

Seventy-eight miles of new track were opened between Emporia and Newton, and the first passenger train chugged into the infant town on July 17, 1871. Along with it came a raucous mob that rode the crest of the railroad’s advance.

“It must be borne in mind that the state of society in that town [Newton] is now at its worst,” the neighboring Emporia News lamented. “The town is largely inhabited by prostitutes, gamblers and whisky-sellers. Pistol shooting is the common amusement. All the frequenters of the saloons, gambling dens and houses of ill-fame are armed at all times, mostly with two pistols.”

And when this element of railhead riffraff collided with the cowboys moving cattle north to the railroad, there was bound to be trouble. A month after the railroad reached Newton, five men were killed and another six wounded in a wild shooting spree that came to be called the Newton General Massacre. When a hastily assembled coroner’s jury returned an unpopular charge of manslaughter against an alleged instigator, the jurors were promptly advised to leave town lest they themselves be lynched.

But soon it was the railhead that was moving on. The cattle business held sway in Newton only for that first year of 1871, when forty thousand head were shipped via the Santa Fe to eastern markets. By the next trail driving season, the spur of the Wichita and South Western Railroad had been built south from the Santa Fe main line, and Wichita—not Newton—assumed the laurels and pitfalls of being a major cow town.7

Construction west out of Newton began in earnest in the early spring of 1872, but now the calendar came into play. Despite a brisk business between Newton and points east, for the Santa Fe to secure its total land grant, the remaining 330 miles of track to the Colorado border had to be completed in another year to meet the ten-year construction deadline.

With the clock ticking, Senator Pomeroy tried to get a congressional extension. But Congress, once the dispenser of unbridled largesse to the railroads, was feeling pressure from the exposure of the Crédit Mobilier scandal, in which promoters of the Union Pacific Railroad had incorporated an allied company and awarded themselves construction contracts at huge profits. But the real scandal occurred when certain congressmen attempted to expose the scheme and then were themselves readily silenced by receiving Crédit Mobilier stock at bargain prices.

No doubt leery of the growing political fallout from the Crédit Mobilier situation, only sixty members of the House of Representatives voted in favor of even allowing debate on Pomeroy’s extension request, and it failed. In this contest, the Santa Fe would be racing the clock.

The railroad’s fate rested in the hands of a hard-driving, hard-swearing construction boss named J. D. “Pete” Criley and his experienced gang of largely Irish laborers. Working for about $2 per day, good money then, they pushed the line west at more than a mile a day during the summer of 1872. Thirty-three miles between Newton and Hutchinson were opened on June 17; another 74 miles on past Great Bend to Larned on August 12. Almost all the route followed in or near the ruts of the Santa Fe Trail.

Along the way, the Kansas Daily Commonwealth reported that on one day alone, Criley’s crews laid 3 miles and 400 feet of track. “This beats anything in the previous history of track-laying in the west,” the paper cheered, apparently oblivious to the Central Pacific’s 1869 record of 10 miles and 56 feet.

With the rush on to extend the railhead with all haste, this early tracklaying was not very refined. Surveyors staked the route, and horse-drawn scrapers hurriedly followed, clearing away the prairie topsoil. Across this rolling terrain, cuts and fills were relatively simple excavations, neither the deep incisions nor high mounds that would be required in mountainous country farther west. Men with shovels and wheelbarrows followed the scrapers to smooth out any ridges or holes.

Next ties were distributed along the right-of-way and then “bedded” into a loose ballast of sand and dirt—a far cry from the tamped gravel ballast of later operations. Because the roadbed was not entirely smooth and the ties were not entirely uniform in size, workers then had to tamp down those ties that were above grade and raise those that were too low by throwing dirt under them.

The clang of rails followed as laborers gripped the long strands with giant tongs and carried them into place from a flatcar inching its way close behind. The rails were dropped at the command of “Down!” and then joined together with tie bars. The rhythmic twang of spikes being driven into wood announced the completion of another thirty-foot section of track.

One thing that Kansas lacked for easy railroad construction was a handy supply of ties. Some were shipped from the more wooded eastern sections of the state and others cut from groves along nearby riverbanks. But as the railroad got farther west, the mountains of Colorado offered a major source, and the Arkansas River—at least when running high in the spring and early summer—promised a ready conduit.

As the Santa Fe advanced past the new town of Great Bend, tie contractors under contract to the railroad for delivery of two hundred thousand ties built an 805-foot containment boom on an angle across the river just east of town. This structure was intended to corral ties that were cut high in Colorado’s mountains and floated some 600 miles downstream.

The plan was to send about twenty thousand ties at a time downstream and have tie wranglers follow the flotilla in small boats and by horseback to herd them along. How successful this particular operation was is not readily known, but hundreds of thousands of ties made their way by water or wagon out of the mountains of Colorado and into the construction camps on the plains.

By now, Holliday’s enterprise—which had started with one locomotive—boasted 15 engines, 19 passenger cars, and a variety of 362 stock, coal, and revenue freight cars. When regular passenger service began between Atchison and Larned, trains covered 291 miles between the two towns in a published timetable of 17 hours and 40 minutes—an average of 16.5 miles per hour. Cost for a one-way ticket was $16.8

Another 60 miles of track put the railhead at Dodge City. No doubt construction boss Criley shuddered for the safety and sobriety of his Irishmen, because the heady times of Newton paled in comparison to the distractions offered by Dodge City.

For starters, “the law” was a rather nebulous concept in Dodge City. The town itself—briefly called Buffalo City after the rapidly vanishing herds—was scarcely a few weeks old when the railroad arrived. According to one observer, it consisted of a dozen frame houses, two-dozen tents, a few adobe houses, several stores, a gunsmith’s establishment, and a barbershop. “Nearly every building has out the sign, in large letters, ‘Saloon.’ ”

Establishing a civil government was far down the list of priorities, but that meant people frequently took matters into their own hands. Witness the case of Jack Reynolds. When Reynolds, described as a “notoriously mean and contemptible desperado,” caused trouble on a train, the conductor “tackled the brute, took the six-shooter away from him and pitched him off the train.” Unfortunately, in the process, the conductor suffered a broken arm that somehow proved fatal. But Reynolds soon got his due. When he tried to bully one of Criley’s men, the tracklayer “put six balls, in rapid succession, into Jack’s body” and he “expired instantly.”9

Dodge City suffered through far worse and more prolonged violence several years later when the Santa Fe opened major cattle pen operations there. Among the leading players then were two brothers named Bat and Ed Masterson. They had arrived in town with the railroad, working to grade 4 miles of the Santa Fe’s line in surrounding Ford County between Fort Dodge and infant Buffalo City in the summer of 1872. But when it came time for Raymond Ritter, one of the many grading subcontractors, to pay them, the brothers received only a few dollars and a promise that Ritter would return shortly with the balance—the sizeable sum of some $300.

As time went by and Ritter failed to reappear, the Mastersons realized that they had been duped. They hunted buffalo and did odd jobs to make ends meet. Then in the spring of 1873, Bat heard that Ritter had been seen farther west at the Santa Fe’s most recent railhead. The rumor was that he was headed east on the next train with quite a roll of cash.

When the eastbound train steamed into Dodge City, young Bat boarded the cars alone, marched Ritter off the train at gunpoint, and soon recovered his overdue account. Ritter was quick to scurry back on board and head out of town, while Bat “led the way to Kelley’s to set up drinks for the cheering, back-slapping crowd” of new admirers. After that, Bat Masterson was “considered a man to be reckoned with” in Dodge.

With a growing reputation, Bat was elected county sheriff in November 1877, defeating a three-hundred-pound tough named Larry Deger by only 3 votes, 166 to 163. Ed Masterson was appointed city marshal a few weeks later. The Masterson boys—Ed was twenty-five and Bat barely twenty-four—were eager to prove themselves.

They got their chance a few weeks later when six armed men tried to hold up Santa Fe trains on the line east of Dodge City. The gang’s first attempt at a water tank east of Kinsley failed when the eastbound passenger train did not stop to take on water as they had expected. The robbers then rode into Kinsley and waited at the depot for the westbound Pueblo Express. In the process, they held the station agent on the platform at gunpoint, but overlooked some $2,000 in the company safe.

As the train pulled into the station, the agent broke free from his captors and shouted a warning to the train crew. As he did so, he leaped across the tracks just in front of the slowing locomotive and used it to shield himself from a hail of gunfire. The train robbers attempted to board the locomotive, but the engineer opened the throttle and sped down the track.

The holdup had been foiled, but the Santa Fe wanted to send a strong message that it would not tolerate such lawlessness. The railroad promptly circulated posters “offering one-hundred-dollar rewards for the capture, dead or alive, of each of the outlaws.”

Bat Masterson organized a posse and captured two of the robbers, Dave Rudabaugh and Ed West, in a blinding snowstorm near Crooked Creek, south of Dodge City. Two other gang members were arrested in town when they showed up with thoughts of busting their comrades out of Bat’s jail. By then the Santa Fe had dispatched a special train to haul the prisoners to the jail in Kinsley. Bat tried unsuccessfully to capture Mike Rourke, the reputed ringleader, but Rourke was arrested in Ellsworth, Kansas, some months later. The sixth gang member was never caught.

In the end, Dave Rudabaugh avoided prison by turning state’s evidence against his captured accomplices, who all served time in Leavenworth. His protestations of turning over a new leaf were without merit, however, and Rudabaugh would go on to a lawless spree in New Mexico—crossing paths with Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid—before being killed by outraged citizens in Chihuahua, Mexico, in 1886.

Bat Masterson’s dogged pursuit of the train robbers added to his reputation and placed him in good stead with the Santa Fe, which would soon have cause to call on his talents again. Ed Masterson was not so lucky. In April 1878, he was summoned to quell a disturbance by Texas cowboys at one of Dodge City’s ubiquitous dance halls. Ed was gunned down when he tried to disarm one of the rowdies, a cowboy named Jack Wagner, but he managed to return fire and mortally wound his assailant.

Bat did not arrive on the scene until a few minutes later. Tall tales to the contrary, he did not go on a wild spree of revenge but lawfully arrested possible participants. They were later released when the dying Wagner confessed to killing Ed.10

Just how wild and lawless Dodge City really was during those cattle years will always be debated, but there is one oft-told story to sum it up. There are as many versions as there were saloons in Dodge City, but the general line has a surly and at least slightly inebriated cowboy boarding a train somewhere along the Santa Fe line through Kansas. When the conductor demanded his ticket and asked where he was going, the fellow retorted that he had no ticket and was going to hell. “Give me a dollar,” replied the conductor, “and get off in Dodge.”

As winter approached the plains in the fall of 1872, Pete Criley’s construction crews pushed the Santa Fe line westward from Dodge City, laying more than 100 additional miles of track. In mid-December they reached the state line—or so they thought. Behind them was a construction season of 303 tough days and almost 300 miles of track since they had struck west from Newton.

But while the men celebrated in the most recent railhead boomtown, “State Line City,” federal surveyors announced that according to their measurements, the state line and the certainty of the railroad’s land grants was still 4 miles away. Criley quickly gathered up those who were sober—and undoubtedly some who were not—and went to work once more.

“ ‘State Line City’ is being removed four miles farther west,” the Hutchinson News reported, “in consequence of the government survey establishing the State line that far from the estimate of the A. T. & S. F. R. R. Company. As the city is built out of tents, we presume that no great difficulty is experienced.”

But with construction materiel running low, Criley had to scavenge assorted rails and ties from back down the line, even tearing up a couple of sidings to get the required rails. Finally, on December 28, 1872, the construction boss was able to wire Topeka rather grandly: “We send you greeting over the completion of the road to the State line. Beyond us lie fertile valleys that invite us forward… The mountains signal us from their lofty crests, and still beyond, the Pacific shouts amen! We send you three cheers over past successes, and three times three for that which is yet to come.”11

But what was yet to come? With its herculean advance across Kansas, the Santa Fe had cut off the parallel Kansas Pacific line some 50 miles to the north from the lion’s share of the cattle trade. But as other railroads built directly into Texas, the Santa Fe itself could not rely on the likes of boisterous Dodge City and other cow towns as its profit centers for very long.

“The road cannot remain on the prairie in the Arkansas valley, but must be pushed on to a profitable terminus in the cattle regions of southern Colorado, and the silver mines of the territory,” the Kansas Daily Commonwealth declared as the state line was reached. “The A. T. & S. F. road will not be completed until it is stopped by the waves of the Pacific, and has been made the fair weather transcontinental route of the nation.”12

But for the moment, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe was financially exhausted by the demands of its frenzied 1872 construction season. While building to the Pacific sounded grand, tapping the markets of Colorado and reaching the New Mexico town of its name were its immediate priorities. Neither would be easy. Up ahead, the Colorado railroad scene was becoming quite crowded.