8

Showdown at Yuma

Amidst the gloom of the panic of 1873, the Big Four’s treasurer announced some rather startling news. While Collis P. Huntington had been aggressively spending money, steady Mark Hopkins had been making it. Despite construction costs on many fronts and the national depression, the Central Pacific had begun to generate substantial profits.

In 1873 the Central Pacific and its branches earned gross revenues of $13.9 million and a resulting net income before bond interest of $8.3 million. After interest on the long-term bonds was paid, a handsome profit of almost $4.8 million remained. This surplus saved the Big Four, corporately as well as individually. Hopkins promptly declared the company’s first dividend of 3 percent, payable in hard currency and not speculative stocks or bonds.

Even Huntington was caught off guard by this timely payout. “The figures are large,” he confessed to Hopkins as bills, too, continued to rise, “but I have gotten used to large figures, and I have more faith that all will yet be well than I had one year ago…”1

Goshen was the terminus of the San Joaquin Valley branch of the Central Pacific. That line cut off from the Western Pacific at Lathrop, just south of Stockton. It was a confusing mix of railroad names, but the ownership was quite simple. All were owned outright or otherwise controlled by Huntington, Stanford, Hopkins, and Crocker.

Once the panic of 1873 was weathered, the direct rail link to the Oakland waterfront provided a steady stream of men and materiel, as tracks were extended up the San Joaquin Valley at a frantic pace. (The San Joaquin River flows generally north between the Sierra Nevada and Coast Ranges, so going south is indeed up the valley.)2

The lure, however, was certainly not local traffic. There wasn’t much in the San Joaquin Valley either. Nor was the Big Four’s promise to the people of Los Angeles enough to drive them on. What led to this flurry of construction was the threat once again posed by Thomas A. Scott. Having gone “to the wall” to save the Texas and Pacific, Scott was determined to push it westward.

Scott’s original charter for the Texas and Pacific anticipated a direct route west along the 32nd parallel from El Paso to Yuma and on to San Diego. Closer inspection, however, showed that endless miles of blazing desert and rugged mountains lay between Yuma and San Diego. Scott asked Congress to approve a change in route that would avoid this terrain, skirt the depths of the Imperial Valley, and arrive in Los Angeles from the east via San Gorgonio Pass.

The problem, of course, was that this was the projected route of the Southern Pacific out of the Los Angeles Basin. When Scott met with Huntington and rather casually suggested that the Southern Pacific should join the Texas and Pacific at San Gorgonio Pass rather than the Colorado River at Yuma, as previously agreed, Huntington’s response was predictable.

If Rosecrans’s paper railroad with solely California ties had caught Huntington’s attention, Scott’s continuing bid for direct transcontinental access to the ports of Los Angeles and San Diego was a call to arms. No one knew what Pacific trade might develop in these sleepy little towns, but Huntington knew for certain that whatever the amount, it would pass through Southern California to the detriment of the San Francisco Bay waterfront that he and his associates controlled.

Huntington countered Scott with an offer to provide the Texas and Pacific access to Los Angeles and San Diego over the Southern Pacific’s rails from Yuma. Huntington made it quite clear to Scott that the Southern Pacific’s destination was Yuma and that Huntington would adamantly oppose Scott’s congressional request for any land grant change west of that point.

Characteristically, Scott stood his ground. With his own railhead still at Fort Worth, some 1,200 miles to the east, Scott replied that if this were the case, he and Huntington would be running competing lines not just between Yuma and San Gorgonio but all the way to San Francisco. That was the same thing that William Jackson Palmer had said to Judge Crocker in Scott’s behalf almost a decade earlier. Thus, the race to Yuma was on, and Huntington responded with all the resources at his command.3

First Huntington had to make good on the Los Angeles vote—as well as collect his subsidies—and connect the Southern Pacific main line with the Los Angeles and San Pedro short line in the Los Angeles Basin. To do so required two marvels of railroad engineering.

The initial challenge was to get out of the San Joaquin Valley. Much of the construction up the valley had been across open country on gentle grades, but at its head at Caliente, the railroad was confronted with the wall of the Tehachapi Mountains. This range continued the Sierra Nevada Divide and blocked easy access between the San Joaquin Valley and the comparable flats of the Mojave Desert leading east to Needles.

The key to the divide, Tehachapi Pass, rose almost 3,000 feet above Caliente in only a few miles. William F. Hood, the Southern Pacific’s assistant chief engineer, took one look and knew that the only solution was plenty of curves and tunnels. So, upward from Caliente the line snaked along knobby, auburn-colored hills studded with piñons and junipers and through narrow, rocky canyons lined with scrub oaks and cottonwoods.

After more than 6 miles of track and six tunnels, Caliente was still plainly visible below, only one air mile away. Two more tunnels, 532 feet and 690 feet, respectively, were drilled by hand, blasted with dynamite, and cleared with shovels. Many of the workers were veteran Chinese laborers, some well seasoned from years of working for Charley Crocker on the Central Pacific.

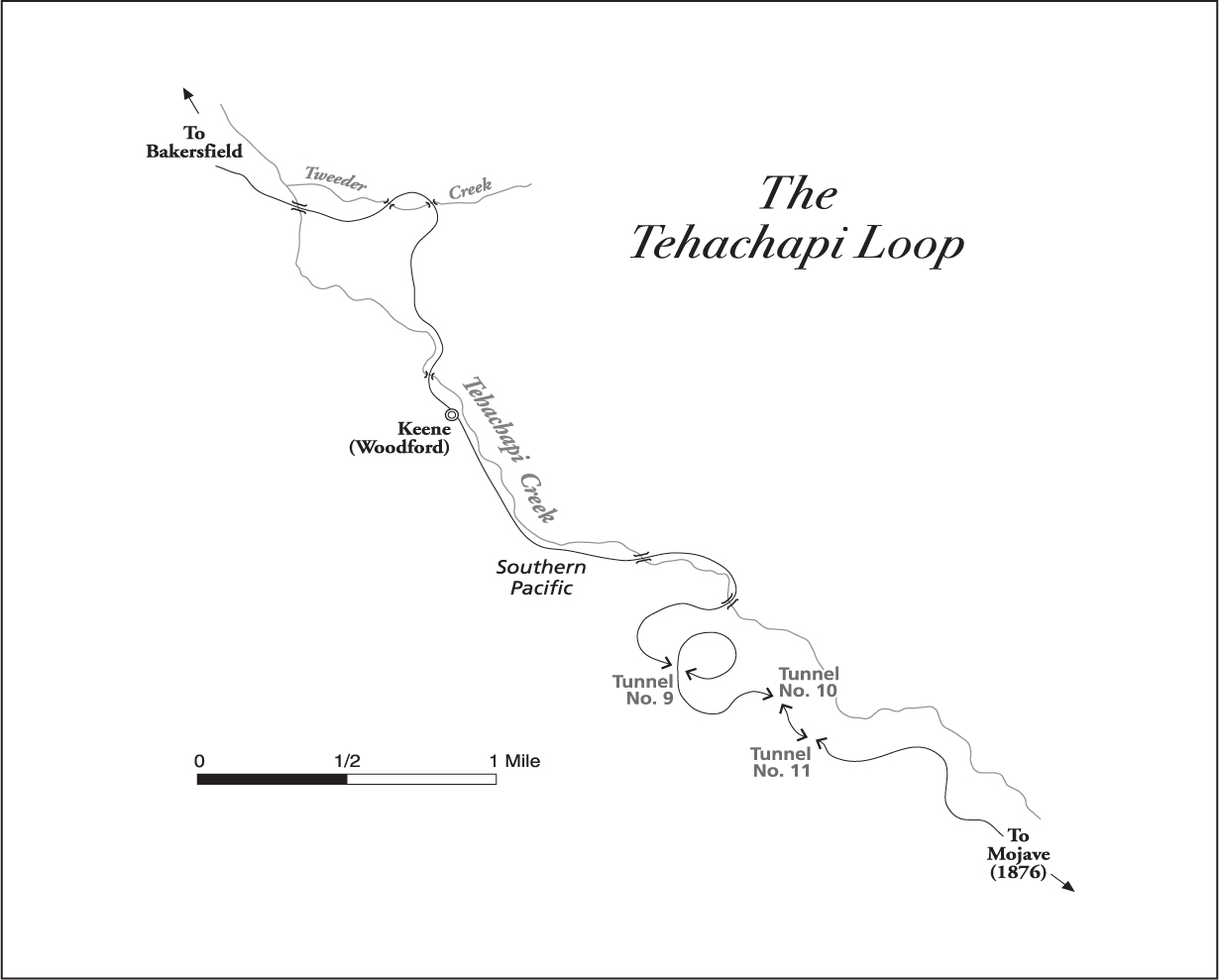

Above Keene (the station there was later called Woodford), at 2,700 feet in elevation, the valley narrowed even more. Holding to a maximum grade of 2.2 percent, the roadbed crossed Tehachapi Creek and then recrossed it in the process of making a climbing semicircle loop. After a rising left curve, Hood lined up the roadbed on a short straightaway and called for tunnel no. 9. It was only 126 feet in length, but it was to be the centerpiece of what came next.

Once through the tunnel, the grade circled steadily left, ascending around a conical hill until it had made a complete 360-degree loop and passed over the track through tunnel no. 9. The design made for a hard-won elevation gain of 77 feet and set up the line for the second half of the climb to the Tehachapi summit.

Above the loop, eight more tunnels were constructed to reach the high point of the pass. It was 28 tortuous track miles from Caliente, almost 1.5 miles of which was through a total of seventeen tunnels. From the pass, construction continued down the relative ease of Cache Creek to the sagebrush flats of the town of Mojave, arriving there on August 8, 1876.

More than a century later, the Tehachapi Loop remains as William F. Hood designed it. Trains over 4,000 feet in length pass over themselves when climbing or descending the route. Dozens of trains wind around the loop daily on what is routinely the busiest single track of mountain railroad in the United States.4

South of Mojave at Palmdale, the Southern Pacific confronted a second barrier to the Los Angeles Basin. Rising above 10,000 feet, the San Gabriel Mountains blocked easy access to Los Angeles from the north. To the northeast, the San Bernardino Mountains culminated in the 11,502-foot San Gorgonio Mountain above the pass of the same name, but this eastern gateway to Los Angeles was almost 100 miles out of the way and intended as the railroad’s exit.

There was one other possibility. A geologic fault between the San Gabriel and San Bernardino mountains had the effect of creating a natural ramp between the Los Angeles Basin and the Mojave Desert. Attention had long focused on a route from the Mojave across the 35th parallel, south of the Grand Canyon. But as more became known about the Colorado Plateau, some looked at the map and thought it plausible to connect Southern California with the Union Pacific at Salt Lake City by building north of the Grand Canyon.

One proponent of such a venture was Senator John P. Jones of Nevada. Jones began by building a narrow gauge line from the piers at Santa Monica, which he helped to develop, to downtown Los Angeles. This provided the town with a second rail link to the ocean, and, after Huntington and the Southern Pacific wrestled control of the Los Angeles and San Pedro Railroad away from local interests, Jones’s line became the hometown favorite. But his Los Angeles and Independence Railroad had bigger plans than simply providing competition for Huntington.

Jones, who had made a princely fortune in silver from Nevada’s Comstock Lode during the 1860s, was interested in developing mining properties around Death Valley, principally near Panamint and Independence, California. The natural ramp between the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains, called Cajon Pass, not only offered a direct route from Los Angeles to Death Valley, but by following the eastern edge of the Mojave Desert, it pointed straight north to Salt Lake City.

“Join hands with our natural allies [Jones’s Los Angeles and Independence] and carry that narrow gauge through the Cajon Pass at a gallop,” cried a local newspaper. “Time is everything, the Southern Pacific operates against us.”

Even without this railroad threat, John P. Jones was not a favorite of the Big Four. The senator was also trying to tax the Central Pacific’s land grant holdings in Nevada—no small thing considering that seven million acres were involved.

While Huntington worked in Congress to amend the Southern Pacific’s land grant to include Cajon Pass, Jones hired a young engineer named James U. Crawford away from Tom Scott’s Texas and Pacific and sent him into the mountains to survey the Cajon route. Making a cursory inspection by horse and buggy, Crawford determined that with 20 miles of track and an 1,800-foot tunnel punched through the sandstone atop the pass, he could be out of the Los Angeles Basin and streaking toward Salt Lake City.

By November 1874, survey stakes lined the pass, but the work was not easy. “We are camped on the summit of the Cajon, about 31 miles north of San Bernardino,” Crawford reported. “It is very cold. Snow among the pines reaches down close to our camp. Bears are numerous, and frequently interrupt our surveying.”

A month later, a crew of rival Southern Pacific engineers and surveyors fresh from the Tehachapi Loop arrived on the Cajon scene. By then, Crawford had laborers felling trees and blasting rock. A wintry rain began to fall, and it pummeled the pass for three days, turning the area into a quagmire of bottomless salt flats and sluice box gullies. By the time falling temperatures and ferocious winds lashed a blizzard across the pass, Crawford’s men were secure in makeshift huts, but the Southern Pacific crew was literally blown out of the pass, tents and all. Score one for Senator Jones’s Los Angeles and Independence.

While Huntington fumed, Crawford’s men drilled their way 300 feet into Cajon’s rocky spine before coming to a stop. Cajon Pass didn’t defeat Senator Jones, but the declining silver prices of the 1870s did. While the Big Four chuckled, Huntington bought the Los Angeles and Independence from Jones for a meager $100,000 in cash, a $25,000 note, and $70,000 in Southern Pacific bonds. Once again, there might be railroads with different names in Los Angeles, but they all had the same owners.5

Meanwhile, Huntington had been taking no chances on reaching Los Angeles from the north—with or without Cajon Pass. Even as work progressed on the Tehachapi Loop, Huntington had workers laboring away at the second of the Southern Pacific’s twin engineering feats. This one was to be a single tunnel over a mile long.

From Palmdale in Antelope Valley, the Southern Pacific’s route climbed to the head of Soledad Canyon and then wound down the Santa Clara River, looking for a way through the western end of the San Gabriel Mountains. Finding none, Hood chose to tunnel through the range just south of Santa Clarita.

Day and night, 4,000 men and 300 animals labored through a mountain of crumbly rock and subsurface water that required extensive redwood timbering. A shaft was sunk near the middle of the tunnel to permit work on four faces at once—inward from each portal and outward in opposite directions from the shaft. When the headings met on July 14, 1876—almost fifteen months after work began—the San Fernando Tunnel was 6,966 feet in length and the longest railroad bore in the world.

On September 5, a special train of five cars loaded with 350 invited guests left Los Angeles and headed north to inspect the results. It took a long ten and a half minutes at about 7.5 miles per hour to make the pitch-black passage, and “time dragged heavily” through what one reporter called “the dark abyss.” But the train emerged to bright sunshine, and at Lang in Soledad Canyon, its passengers found “an army of about 3000 Chinamen standing at parade rest with their long-handled shovels” in a line on either side of the roadbed.

Charley Crocker greeted the Los Angeles contingent, and an hour later a similar special arrived from the north carrying Leland Stanford and dignitaries from San Francisco. They all watched as two crews working from opposite directions laid the remaining 500 feet of track in a contest that lasted all of eight and one-half minutes.

Crocker then drove a golden spike to signal the completion of the line from San Francisco, around the Tehachapi Loop, through the San Fernando Tunnel, and into downtown Los Angeles. The Southern Pacific men, the Los Angeles Evening Express enthused, “have not only lived up to the letter of their promises, but in the face of difficulties that were fairly gigantic, they have reached Los Angeles sooner than the most sanguine of us expected.” The next day, regular service was inaugurated between San Francisco and Los Angeles, with express trains making the run in twenty-four hours.6

The answer was obvious to any interested observer. San Diego could wait. While Tom Scott plugged away in Texas, and Colonel Holliday’s Santa Fe still struggled in Colorado, the Southern Pacific would build east out of Los Angeles, control San Gorgonio Pass for itself, and race southeast across relatively open country to the Colorado River crossing at Yuma.

To counter competitors’ claims—Scott was the most vocal—that the Southern Pacific’s advances amounted to nothing short of a railroad monopoly in the West, Huntington tapped a California businessman named David D. Colton to be his lieutenant and, for a time, the figure-head president of the Southern Pacific. Red haired, heavy set, and with a mercurial temper, Colton was an odd choice. But he had Charley Crocker’s blessing, and in the press of business, Huntington concurred.

Colton’s tenure with the Big Four was to be tumultuous and short lived. He would die in 1878, and for years his widow would carry on a highly public feud with the Big Four for his alleged interests. But for the present, Huntington was Colton’s alter ego, and Colton pushed the Big Four’s plans as strenuously as anyone. This was particularly true when it came to besting Tom Scott, whether in the halls of Congress or among the sand dunes of Yuma.

In trying to jumpstart the Texas and Pacific after the panic of 1873, Scott sought to add a federal subsidy to the land grant that the railroad had already received. Shrewdly, he tied his request to the growing reconciliation with the South and lobbied for southern congressional support by arguing that a subsidy for a southern road was but a narrow slice of the federal largesse that had been benefiting northern railroads since the end of the war.

Huntington countered by saying that the Southern Pacific would build the South a southern transcontinental between Yuma and El Paso without subsidies other than the land grant already awarded to the Texas and Pacific. Scott dug in his heels, of course, and firmly opposed any transfer of the land grant as well as any authority for the Southern Pacific to expand outside its present charter limits of California.

“Scott is making a very dirty fight, and I shall try very hard to pry him off,” Huntington told his new front man Colton, “and if I do not live to see the grass growing over him I shall be mistaken.”

Huntington was quite capable of planting his own innuendo. Scott could play the monopoly card against the Big Four, but Huntington countered that what Scott was really after was the formation of a Pennsylvania Railroad–dominated transcontinental system such as Scott had sought earlier with the Kansas Pacific.

All Scott had to do, Huntington told his southern friends, was turn the eastern axis of the Texas and Pacific northeast and point it toward St. Louis instead of Memphis, and the South would be left without a transcontinental link. Huntington, on the other hand, promised that if the Southern Pacific were given free rein to race east, it wouldn’t stop until it reached New Orleans.

“We must split Tom Scott wide open if we can and get rid of him…” Colton told Huntington. “He is the head and front at this time of all the devilment against the C.P. & S. P.… He is today the most active and practical enemy, we have in the world.”7

And Scott appeared to hold a powerful advantage in at least one respect. The Southern Pacific’s own 1866 congressional land grant extended eastward only to the California-Arizona border, presumably the middle of the Colorado River. There was no hope for similar land grants in Arizona and New Mexico as long as Scott and the Texas and Pacific were opposed.

So instead Huntington used all means possible to secure a franchise from the Arizona legislature for a simple right-of-way across the territory. There was no land grant involved because almost all land was federally owned, but the territorial legislature could convey a right-of-way for public purposes across such land under authority granted to states and territories by the Right-of-Way Act of 1875.

Wanting no delays, Charley Crocker inspected the Yuma crossing in the spring of 1877 and selected sites for a bridge. Several miles downstream from its confluence with the Gila, the Colorado cut through a low line of sandy-colored bluffs. While generally flowing north to south, the big river was making one of its many twists and turns and was actually running east to west at this point. Just below the bluffs, the river was still somewhat constrained by high banks that offered suitable abutments for a bridge.

To cover all bases, Crocker obtained a bridge charter from both the state of California and the territory of Arizona. But reaching the crossing with rails from the California side presented its own set of legal problems. The Fort Yuma Military Reservation occupied the California bank, and in order to access the bridge site, Southern Pacific tracks had to cross military land, something that required the permission of the secretary of war.

Crocker started up the chain of command with General Irvin McDowell, who sixteen years earlier had been the Union’s scapegoat at the First Battle of Bull Run. Now McDowell was in charge of the army’s Department of the Pacific, with headquarters in San Francisco. Showing McDowell the plans for the bridge, Crocker argued that it would be of little value unless track could be laid across the reservation to reach it.

McDowell passed the request on to Secretary of War George McCrary, who immediately came under intense lobbying pressure—for and against—from Huntington and Scott. Deciding to pass the buck, McCrary ruled that only Congress could permanently decide the issue. But in the interim, he gave the Southern Pacific permission to lay temporary tracks across the reservation, so long as the railroad agreed to remove them if Congress denied the right-of-way. In order not to show favoritism to the Southern Pacific, McCrary accorded the same arrangement to the Texas and Pacific, even though its railhead was 1,000 miles away.

While McCrary’s action created some uncertainty for the Southern Pacific, Huntington was not one to hesitate. He had long believed that it was far better to ask for forgiveness afterward than to sit idly waiting for permission beforehand. So, in July 1877, work started on the Yuma bridge from the California side. It was to be 667 feet long and include a swinging drawbridge that would allow steamships to pass up or down the Colorado River.

About this time, the majority of troops at Fort Yuma were ordered north to Idaho to join the pursuit of Chief Joseph and his Nez Perce Indians. Only Major T. S. Dunn, one sergeant, and two privates were left at the fort. Early in August, Dunn inspected the Southern Pacific’s “temporary” tracks as they were being laid across the reservation. They certainly had a look of permanence about them, and Dunn reported that fact to Secretary of War McCrary. In reply, the secretary telegraphed an order to halt all construction on the tracks and the bridge immediately. By that time, however, rails were within a few yards of the half-built bridge.

Not to be denied, Crocker insisted to General McDowell that the half-built bridge was likely to be destroyed by the river’s current unless the Southern Pacific was able to salvage it. More telegrams were exchanged, and on September 6, McCrary authorized enough work on the bridge structure to protect it from destruction. Crocker intended to do just that, but rather than pulling up piles, he secured the bridge from damage by rapidly completing the structure and anchoring it firmly to the Arizona bank of the river.

“So far as going on and finishing the bridge is concerned,” Crocker wrote Huntington, “we have given orders to our men there not to quit till they feel the point of the bayonet in their rear.…”8

The completed bridge had six spans of 80-foot wood trusses supported by piers and pilings driven into the hardpan of the riverbed. On the Arizona side, the draw span was 93.5 feet in length. It rested on the final pier of the truss sections and pivoted on another pier near the shore to allow boats to pass through the deepest part of the channel. Toward the Arizona shore from this pivot pier, which would later be replaced with a circular concrete foundation, a wooden truss ran to the riverbank.

Once the bridge decking was in place, spiking rails across it could be done in a few hours. Under orders from Secretary McCrary, poor Major Dunn was forced to mount a rotating guard with his four-man garrison to prevent that from happening. But it was Crocker who had ready and effective reinforcements close at hand. Surmising that the U.S. Army would not interfere with a civilian train carrying mail and passengers—particularly if it were to be wildly welcomed by the citizens of Yuma—he dispatched just such a special from San Francisco.

Major Dunn and his outnumbered troops stood guard on the bridge until eleven o’clock on Saturday night, September 29. Assuming in the manner of the time that no laborers would work on Sunday, Dunn and his men then retired. But their sleep was interrupted a few hours later by the dull thuds and throaty clangs of rails being dropped into place. Crocker’s crew had no such apprehension about toil on the Sabbath.

Dunn and his troopers hurried back to the bridge, but they were literally bowled out of the way by a carload of rails being pushed ahead of a Southern Pacific locomotive. Recovering, Major Dunn ordered the foreman placed under arrest. The man’s reply was less than courteous and certainly not compliant. Outnumbered by the construction crew as they were, Dunn and his three soldiers could do little but stand aside as another half mile of track was spiked down into the center of Yuma.

Dawn Sunday morning, September 30, 1877, was announced by the shrill blasts of the first locomotive in Arizona. Yuma’s citizens poured into the streets to give it a hearty reception. After a crew on a handcar inspected the new track, Crocker’s San Francisco Express, gaily bedecked with American flags, rolled into town to a similar reception. Crocker telegraphed Huntington with the news: “Bridge across Colorado complete and train carrying United States mails, passengers and express crossed over to Arizona side of river this morning. People of Yuma highly elated over the event.”

While Yuma cheered, the battle with the army reverted to the telegraph wires. General McDowell, who may have been feeling as snookered here as at Bull Run, ordered all the reinforcements that he could muster—“one officer, twelve soldiers and a laundress” from San Francisco—and dispatched them posthaste to Yuma. By train.9

But how could the U.S. Army declare war on the very institution that was winning the West? In a flurry of support that Southern Pacific operatives no doubt encouraged, if not outright orchestrated, Yuma’s mayor, town council, and leading merchants, as well as Arizona’s territorial governor, besieged Washington with pleas not to deprive them of their railroad.

“By the completion of the Southern Pacific Rail Road to Yuma a new era seemed to have dawned upon the Territory,” almost one hundred Yuma residents petitioned Secretary of War “McCreary,” spelling his name wrong in the process. “By prohibiting the completion of the bridge at Yuma,” they asserted, “our goods are landed on the California side of the Colorado river without shelter from the sun or storms.” They considered it “an outrage to be put to the inconvenience and delay of an expensive and dangerous ferry” when trains could be run into the city.10

The San Francisco Daily Alta California added its voice to the fray. In the face of this accomplishment, what was the government to do, the paper demanded with due sarcasm, order “Stanford and Company to work pulling up those piles with their teeth” or “… set us back to the days of Forty Nine, when we crossed the river in a basket covered with the skin of a dead mule?”

The answer was, hardly. “I do not believe they [the government] will interfere with the mail and passengers, after the track is completed,” David Colton wrote to Huntington, “but at any rate I think it is a good climate on the Arizona side in which to winter an S. P. locomotive, should they cut us off, & it will be a check to our friend Thos. A. Scott.”11

It was Huntington who got the government’s answer firsthand and at the highest level. The bridge matter was debated in two cabinet meetings, and Secretary of War McCrary’s referral to Congress affirmed, but on October 9, Huntington called at the White House to see President Rutherford B. Hayes.

“I think I have the bridge question settled,” he reported to Colton afterward. “I found it harder to do than I expected.” According to Huntington, Hayes was at first angry and scolded Huntington that the Southern Pacific had defied the government.

But then Hayes asked, “What do you propose to do if we let you run over the bridge?” Why, push the road right on through Arizona, Huntington replied. “Will you do that?” the president queried. “If you will, that will suit me first rate.” Hayes promptly issued an order to permit train service across the reservation and into Yuma.12

But there would be no rapid construction eastward across Arizona. This time, the nemesis was not the government, nor the terrain, nor even Tom Scott. This time Huntington’s partners simply refused to fund another wild expansion. Having gotten a whiff of the dividends that came from an operating profit, all but Huntington were strongly opposed to extending the Southern Pacific until their enormous Central Pacific debt could be brought under control.

Despite his enthusiasm in reaching Yuma, Crocker was quick to assure Huntington that “taking all things into consideration, I feel that we have all the railroad property that we can well afford to own, and that I would like to get a few eggs in some other basket.”

Huntington did not give up the idea, of course, but by January 1878, Crocker’s resolve had hardened. “I notice what you say about the importance of doing some work on the Southern Pacific road east of Yuma,” he told Huntington. “I answered that proposition in a late letter which I wrote you. We have no money to spend there now.”

Even Huntington’s old hardware store partner, Mark Hopkins, shook his head when Huntington asked Hopkins, Stanford, and Crocker to endorse a stack of blank promissory notes so that Huntington might fill them in as required—the ultimate “blank checks.” For the moment, Yuma was the end of the line. Huntington had to be content to control the river crossing there and wait to see what rival might emerge from the chaos in Colorado or the financial woes of Tom Scott in Texas.13

But there was to be one indirect casualty from the bridge battle at Yuma. Mark Hopkins had not been well for much of the preceding year, complaining in particular of rheumatism. A Chinese herb doctor treated his maladies, and as he showed some improvement, he chose to escape the damp winter cold of the Bay Area and head for warmer climes. Perhaps because Huntington had routinely criticized his partners for never having seen entire sections of their expanding empire, Hopkins decided to combine his desire for hot, dry air with an inspection of the bridge that had caused so much fuss.

There was no question that Hopkins would be accorded a private car. Accompanied by some Southern Pacific bigwigs, including the railroad’s chief physician, his train chugged south and arrived at Yuma. On the evening of March 28, 1878, while his private car sat on a siding there, Hopkins stretched out on a couch and appeared merely to take a little after-dinner nap. One of the company’s construction engineers later heard Hopkins give a deep sigh and, knowing that it was close to the punctual man’s bedtime, tried to rouse him. The doctor was hastily summoned, but the detail person of the Big Four was dead a few months short of sixty-five.14