9

Impasse at Raton

While his associates momentarily shackled Collis P. Huntington from further expansion, the other southwestern railroads slowly emerged from the economic hangover of the panic of 1873. During this time, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe secured its own rail access eastward from Topeka into the railroad hub of Kansas City. The moves were complex and the number of subsidiaries involved was mind numbing, but the resulting connection was as significant of a transcontinental step as any the Santa Fe had taken previously. In time, it would look to extend even farther east.1

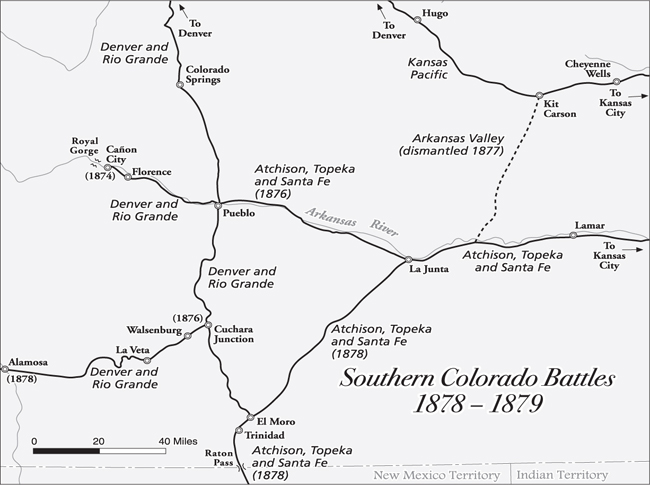

Out west, after a two-year pause just inside the Colorado border, the Santa Fe continued construction up the Arkansas Valley toward Pueblo, reaching La Junta in 1875 and Pueblo itself early in 1876. After a similar construction hiatus, the narrow gauge Denver and Rio Grande built south from Pueblo and extended 50 miles to Cuchara Junction (near present-day Walsenburg). Here the Rio Grande line forked with the western leg following the Cucharas River to La Veta, and the other leg, continuing south toward coalfields near Raton Pass.

It would have been an easy matter for the Rio Grande to build into the town of Trinidad at the foot of Raton Pass. Certainly Trinidad cheered the railroad’s advance. But William Jackson Palmer had other ideas. Fresh from his land development successes at Colorado Springs, the general chose to halt the Rio Grande about 4 miles north of Trinidad and establish the new town of El Moro. It was a development strategy that he would employ time after time. But while Palmer and his circle of investors profited from the resulting land speculation, the technique hardly endeared them to the existing towns that were left without a railroad.

In the case of El Moro, the town fathers of Trinidad were outraged. Some saw the founding of the new town as outright blackmail by the Rio Grande to induce Trinidad and surrounding Las Animas County to vote bonds to aid the railroad’s construction. Even as the Rio Grande paused at El Moro, Trinidad was hotly debating just such a bond issue to support the Kansas Pacific in building to Trinidad.

The third railroad with its eyes on Trinidad was the Santa Fe. Holliday’s road had made no bones about its ultimate destination since adding the town of Santa Fe to its Atchison and Topeka moniker before it had laid a single rail. Now its management saw an opportunity en route to be welcomed into Trinidad as heroes. After Las Animas County rejected the Kansas Pacific bond issue and local sentiment turned against the Rio Grande because of its halt at El Moro, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe became the hometown favorite in Trinidad.

The Denver and Rio Grande was completed to El Moro on April 20, 1876. Regular passenger and freight service was inaugurated within a week, and the railroad-sponsored town promoted itself as the logical terminus of stage and freighting operations to and from New Mexico—to the detriment of Trinidad. By the end of the summer, three hundred people were living in El Moro, and several companies had built freight warehouses there.

Palmer, however, was not pleased with the overall results. Too many freighters continued to haul goods by wagon over the old Santa Fe Trail between Trinidad and La Junta directly to and from the Santa Fe Railroad. Some freighters from the San Luis Valley did the same thing, avoiding the Rio Grande’s La Veta branch and hauling goods to and from the Santa Fe’s railhead at Pueblo instead.

The advance of the Santa Fe up the Arkansas River to Pueblo had already disrupted the cozy relationship that Palmer and the Rio Grande had with the Kansas Pacific for connecting east-west traffic. Before the Santa Fe’s encroachment, the Rio Grande funneled traffic along Colorado’s Front Range to and from the Kansas Pacific at Denver. Thanks to the Santa Fe’s recent direct connections to Kansas City, it could now compete head-to-head with the Kansas Pacific for east-west traffic.

In theory, Palmer and the Rio Grande should have been in the cat-bird seat. By adjusting its rate structure between Denver and Pueblo, the railroad could direct traffic either northward to the Kansas Pacific at Denver or southward to the Santa Fe at Pueblo. But as the Santa Fe got more and more of the southern Colorado traffic directly, the Kansas Pacific cried foul.

Somewhat warily, the three roads entered into a pooling arrangement that required the Denver and Rio Grande to divide its business between the Kansas Pacific and the Santa Fe with the understanding that the Kansas Pacific would not build to Pueblo and the Santa Fe would not build to Denver. This arrangement proved short lived, however, and was soon “crumbling beneath the pressures of mutual distrust and conflicting ambitions.”2

A major source of the friction was Colorado’s slumbering mining prospects. They were finally beginning to attract attention. A muddy impediment to placer gold mining proved to be residue from silver ore, and by 1877, a rush began for Leadville and a host of other silver mining camps in Colorado’s mountains.

There would be no lack of competitors attempting to build out of Denver to tap this bonanza—John Evans’s Denver, South Park and Pacific, and William Loveland’s Colorado Central among them—but one major name was to be absent from the race. In fact, it also disappeared from the contest to reach Santa Fe.

The Kansas Pacific’s construction deal with the Denver Pacific had been calculated to speed the road to Denver and a connection with the Union Pacific, not permanently dissuade it from a southwestern bent toward Santa Fe. But the panic of 1873, growing competition from the Santa Fe, and the Kansas Pacific’s failure to secure Las Animas County bonds had taken their toll. Instead of racing the Santa Fe and the Rio Grande to Pueblo or Trinidad, or heading south into New Mexico, the Kansas Pacific simply abandoned the field and waited for the Union Pacific eventually to absorb it.3

The Kansas Pacific’s retreat left the Denver and Rio Grande and the Santa Fe to slug it out for both Colorado traffic and the long-sought gateway to New Mexico and beyond. Although owing certain subservience to his East Coast investors, General Palmer was clearly in command of the Rio Grande. As a confrontation with the Santa Fe loomed, that railroad had two equally forceful and effective leaders at its helm. In some respects, their relationship and roles resembled those of J. Edgar Thomson and Thomas A. Scott.

The senior member of the Santa Fe team was Thomas Nickerson, a leading member of the railroad’s “Boston crowd” of investors. Born in Brewster, Massachusetts, in 1810, Nickerson came from a long line of New England sailors. He spent almost thirty years at sea before investing his profits on land. By 1870, he was a major Santa Fe shareholder. Nickerson became the railroad’s vice president in 1873, and a year later, the board of directors decided that the seasoned sailor was the man to serve as president and lead them out of the financial woes of the panic of 1873. Both cautious and tenacious, Nickerson was slow to change course, but unafraid to sail into the wind.

Nickerson’s conservatism sometimes frustrated his right-hand man, but once William Barstow Strong received go-ahead orders, Strong knew that he had Nickerson’s full support. Born in Vermont, Strong was almost twenty-seven years Nickerson’s junior. After business college in Chicago, he went to work as a station agent and telegraph operator for the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad. Progressively more responsible jobs with Midwest railroads followed, including two tours with the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy. The Santa Fe hired Strong away from the Burlington to become its general manager in 1877, and six weeks later, Strong was also named vice president. Between the two of them, Nickerson and Strong would see the Santa Fe through a far-flung expansion.4

If Nickerson’s and Strong’s names are not as well known to later generations as those of rail barons Huntington or Jay Gould, it is not because their accomplishments were any less but rather that they undertook them with less bravado. Aside from Holliday’s occasional crowing of his founding role, the Santa Fe management was much more of a team effort than many other roads. While Huntington roared between Washington politics and New York finances, and Gould fixated the high and the mighty of Wall Street with his deals, Nickerson and Strong stayed largely out of the public eye—quiet, efficient, and determined of purpose, but no less calculating.

And so the battle was joined. Long after the conflict at Raton Pass, George S. Van Law, who at the time was a young surveyor with the Santa Fe, termed the Denver and Rio Grande as having been “cocky and resolute.” Van Law recalled that the railroad “believed in a future life and believed in setting its stakes in the beyond, and doing it first.”

To be sure, “cocky and resolute” was probably an apt description of Palmer and his associates. After all, they had pretty much been given free rein over a sizeable chunk of Colorado. Certainly their interest in a railroad across Raton Pass dated back to Palmer’s 1867 survey for the Kansas Pacific. But somewhere along the line, their bold plans and long-held dreams ran afoul of the Right-of-Way Act of 1875.

This was the same act that had permitted Huntington and his Southern Pacific cohorts to secure a right-of-way on the Arizona side of the Colorado River from Arizona Territory. Under the act, any state or territory could grant a railroad a right-of-way across the public domain, but such company was required to file a plat (survey) and profile of its intended route with the U.S. General Land Office to establish its priority over subsequent claimants. Otherwise the first party to begin actual construction controlled the route.

Well after the Right-of-Way Act became law, Palmer cabled his close friend and business associate Dr. William A. Bell what amounted to his manifesto. “It is understood you understand,” Palmer wrote, “that we stop not until San Luis Park is reached, and I hope not until Santa Fe although for manifest reasons we hold open question of route to New Mexico whether from Trinidad south [Raton Pass] or Garland south [La Veta Pass].”5

Why then did Palmer fail to file the required plat for the Raton Pass route? With his own railhead at El Moro within sight of the pass and the Santa Fe still 60 miles away at La Junta, Palmer may well have tried too hard to outfox the Santa Fe by masking his intentions. He may have thought that his earlier explorations there preempted the field, or he may have been distracted from the details by his many other ventures: land speculation, coal mines, and even railroads in Mexico.

None of this, however, seems to excuse what in hindsight appears as both a monumental corporate blunder and the first of two history-changing moments in western transcontinental railroad construction. Palmer, who was so meticulous in so many things, overlooked or chose to ignore the filing requirements of the Right-of-Way Act. Too late, the general realized that he had to take immediate steps on the ground to seize the key passage at Raton.

The Santa Fe approached the matter very differently. First, William Barstow Strong secured a charter from New Mexico for construction south from Raton Pass. Then one of the Santa Fe’s engineering assistants, William Raymond Morley, spent several weeks surveying the Raton slopes disguised as a Mexican sheepherder.

Ray Morley was, in fact, the quintessential railroad surveyor. As his obituary opined, “he was no respecter of rules until he had proved them in his own way” and “he asked no man to go where he was not willing to lead.”

Morley was born in Massachusetts in 1846. Orphaned quite young, he ended up with an uncle in Iowa, where he later lied about his age and joined the Ninth Iowa Volunteer Regiment of the Union army during the Civil War. He got an early look at the business of railroads—albeit destroying them—while following General William Tecumseh Sherman through Georgia. Back in Iowa, he entered Iowa State University but was forced to drop out after his second year for lack of funds.

Morley found work as a land surveyor around Sioux City and on the Iowa Northern Railroad. Then he went to work for William Jackson Palmer on the Kansas Pacific. The general must have had his eye on the young ex-private, because when Palmer’s wide-flung interests came to include the sprawling Maxwell Grant in northern New Mexico, a vestige of historic Spanish land grants, Palmer offered Morley a surveying job there. By November 1872, Morley had been promoted to manager.

With this respectable job in hand, Morley hurried back to Iowa and married Ada McPherson. After a five-year courtship of mostly letters, this genteel, golden-haired twenty-year-old followed her new husband to the headquarters house of the Maxwell Grant in Cimarron, New Mexico. Ada quickly took to the lifestyle, and the couple was soon involved in the rough and tumble of territorial politics.

When the Maxwell Grant changed ownership yet again, Morley spent the summer of 1876 surveying for the Denver and Rio Grande on its line over La Veta Pass, including laying out the corkscrew of Mule Shoe Curve. Exactly when and why he came to throw his allegiance to the Santa Fe is uncertain. It seems probable, however, that Morley disdained Palmer’s heavy-handed rival town techniques and thought that the Santa Fe was likely to have a larger role in New Mexico than the Rio Grande. So the wiry figure wrapped in a serape carefully avoided the Rio Grande surveyors who were also at work on Raton and quietly made his own calculations.6

On February 20, 1878, William Barstow Strong and President Thomas Nickerson met in Pueblo to map out their next course of action. That Nickerson should be so far from Boston and out on the road in the middle of winter is evidence that the Santa Fe viewed these next steps as critical to the railroad’s future. “Of course we have no certain means of knowing what was going on,” Pueblo’s Colorado Weekly Chieftain reported of the two men’s joint appearance in town, but “it is predicted by those who know that the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe company will make a big jump when it does start.”

A week later, while acknowledging, “The air is full of railroad rumors, but nothing reliable,” the Chieftain wryly noted that the Santa Fe had appointed a superintendent of construction, and, “as railroad companies do not appoint superintendents of construction unless they mean to construct something, this looks like business.”7

It was. Nickerson authorized Strong to build south from the Santa Fe main line at La Junta in whatever manner Strong thought best. Rather than starting at La Junta, Strong chose to secure the entire route into New Mexico by immediately undertaking the first flurry of construction in the section of Raton Pass that would admit only one set of tracks. Thus began one of the most oft-repeated episodes of the western railroad wars—a story in which it has always been difficult to sort fact from fiction.

Upon receiving the go-ahead, Strong immediately ordered construction engineer A. A. Robinson to take a grading crew and seize what Ray Morley had determined to be the key stretch of the Raton route. Robinson was in Pueblo at the time, and he sent a telegram in cipher to El Moro ordering Morley to assemble a Santa Fe work crew in secret. Ironically, Robinson then took the Denver and Rio Grande train from Pueblo to El Moro, arriving there shortly after midnight in the wee hours of February 27.

On the same train was the chief engineer of the Denver and Rio Grande, J. A. McMurtrie. Reports vary as to whether the two men were aware of each other’s presence on the train and who went to sleep upon arriving in El Moro and who didn’t. McMurtrie is thought to have slept for several hours, while Robinson reportedly secured a horse and immediately rode through the night to Uncle Dick Wootton’s place on the northern slope of the pass.

Richens Lacy “Uncle Dick” Wootton was one of those truly legendary characters. Call him Indian fighter, scout, trader, rancher, self-promoter, moonshiner—he was at least a little of each. Wootton had earned his familiar sobriquet of Uncle Dick by arriving in the fledgling town of Denver at Christmas 1858, promptly breaking open two barrels of “Taos Lightning” whiskey, and offering the welcome refreshment to any and all takers free of charge. By evening, he was everyone’s favorite uncle.

In 1865 Wootton secured charters from the territorial legislatures of both Colorado and New Mexico for a toll road from Trinidad to Red River, New Mexico, via Raton Pass. (The latter half toward Red River was certainly not a railroad route, but it was one way to get travelers to the Rio Grande above Taos and Santa Fe.) By some accounts, the Santa Fe tried to buy Wootton’s toll road, but Uncle Dick turned them down. In exchange for a right-of-way, he simply asked the railroad to give him and his wife free passes and a lifetime credit of $50 per month at the general store in Trinidad.

Arriving at Wootton’s place after his nighttime ride, Robinson met Morley, and with Uncle Dick along, the men organized the gang of workers who had gathered on Robinson’s orders. By five o’clock in the bitter cold of the dark, wintry morning, they began to pick at rocks and to shovel dirt by lantern light “at three of the most difficult points in the pass.”

Rio Grande engineer McMurtrie, whether he had slept or not, assembled a similar work gang in El Moro and headed south toward the slopes of Raton at an equally early hour. By some accounts, his party arrived on the scene not more than thirty minutes after Robinson’s crew had begun to scrape away at the mountainside. How many threats were exchanged between the rival groups—apparently there were armed men on both sides—varies with the telling, but the fact remained that there was only enough room in the canyon for one railroad grade, and the Santa Fe men were in possession of it. If the Rio Grande was going to dislodge them, McMurtrie’s workers would have to resort to force.

Some secondary accounts report that veteran Dodge City marshal Bat Masterson was in the employ of the Santa Fe and soon arrived on the pass with a gang of gunslingers to support the Santa Fe position. This seems unlikely and a confusion with Masterson’s later role in the Royal Gorge war. Bat’s brother, Ed, was killed that April in Dodge City, and Bat was present there. Masterson was certainly a Santa Fe ally, but his reported appearance at Raton may have been confused with only boastful threats of his pending arrival that Santa Fe men may have made to bolster their position.

With the numbers in each party about equal, a tense standoff continued until the Denver and Rio Grande crew finally withdrew, hurling a few last threats over their shoulders. McMurtrie had them make a half-hearted effort to excavate in nearby Chicken Creek (present-day Gallinas Creek) before deciding that it was not a suitable alternative.

The Denver and Rio Grande had lost its long-planned route to Santa Fe. But one more question must be asked of Palmer’s tactics. Having been blocked at Raton Pass, why didn’t he build across the Raton Mountains via Trinchera Pass, some 35 miles to the east? Given its railhead at El Moro, the Rio Grande was poised to skirt Fishers Peak in that direction, and quick construction might have leapfrogged the Santa Fe as it wrestled with the upper slopes of Raton. Dr. Bell and others had viewed Trinchera Pass favorably on the 1867 Kansas Pacific survey, although Palmer never seemed enamored with it.

Most likely, once the Rio Grande arrived at El Moro, Palmer saw Trinchera Pass as too great a detour east on the line toward Santa Fe and assumed that he would be able to reach the New Mexico capital by extending the La Veta Pass line down the upper Rio Grande. Of even greater concern, perhaps, was the fact that the increasing lure of the Leadville and San Juan mining trade focused his attention in that direction rather than eastward around Raton.8

Having won the field, the Santa Fe set about building its line across Raton Pass. Construction started in earnest from La Junta, and when the first Santa Fe train chugged into Trinidad on September 1, 1878, the town that had been spurned by the Denver and Rio Grande celebrated with great enthusiasm. More than a century later, Trinidad remains bound to the Santa Fe.

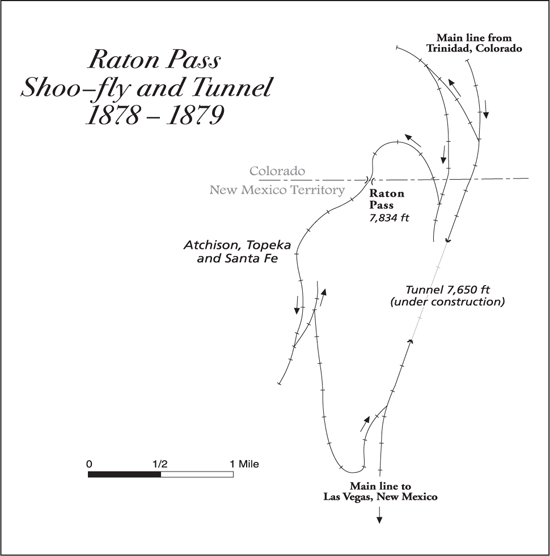

The arrival of the Santa Fe main line in Trinidad brought heavier equipment for the difficult work higher on Raton Pass. A. A. Robinson laid out the grade up the canyon of Raton Creek and then just at the Colorado–New Mexico line—a stone’s throw from Uncle Dick Wootton’s place—he called for a tunnel to burrow under the crest of the pass. Traffic could either wait for its completion or a temporary track would have to be built.

The urgency the Santa Fe felt in building into New Mexico dictated that while work went forward on the tunnel, Robinson lay out an ingenious ladder of switchbacks that permitted trains to stair-step their way over the pass. Coming upgrade from Trinidad, the main line passed a siding and then entered a deep cut leading to where crews were excavating the tunnel. Then a switch was thrown behind the train, and it backed up a switchback until it had passed over another switch and onto the leg of a Y. This switch was thrown, and the train moved forward to a second Y where another change in direction left it backing up around a curve and over the summit.

On the New Mexico side of the pass, with the train still backing but now going downgrade, it came to another Y and backed in. When that switch was thrown, the locomotive steamed forward and downhill to the second Y on the New Mexico side. It pulled to the end of that leg. Then once that switch was thrown, the train backed down the remaining grade and around a curve and over a switch onto the main line, where it would emerge from the southern end of the proposed tunnel.

This laddered run-around—a “shoo-fly,” as railroaders call it—above the Raton Tunnel site hardly made for an express run, but it did permit passengers and freight to ride rails all the way from Kansas City to the advancing railhead in New Mexico. More important, it allowed men and materiel to push the railhead forward while the tunnel was still under construction.

With grades of 6 percent, it also required the Santa Fe to expand its motive power. The lighter American-type locomotives that had served the road well across the plains of Kansas lacked the power to move heavy cars over this mountainous terrain. To meet the demand, the Baldwin Locomotive Works built consolidation-type locomotives. The first model bore the number 204, but in consideration of the locale in which it was to serve, the name “Uncle Dick” was soon emblazoned on its cab in honor of Raton Pass’s most famous resident.

The Uncle Dick was the largest locomotive yet built by Baldwin. It had a wheel configuration of 2-8-0—a set of two pilot wheels, four sets of two drivers, and no trailer wheels under the cab. (By comparison, the American types had 4-4-0 wheel configurations, providing only four driving wheels.) But there was one other special adaptation. While the total wheelbase of the drivers was fourteen feet, nine inches, the first and third sets were equipped with tires instead of flanges so that the rigid wheelbase between the second and fourth sets was less than ten feet. This meant that the locomotive could more readily follow the tighter curves on the line.

Not only was the beefier Uncle Dick more than equal in pulling capacity to two standard road engines, but also its operating costs were only a little more than that of one American-type locomotive. These innovations and their resulting efficiencies cemented a long relationship between the Baldwin Locomotive Works and the Santa Fe, and in time, Baldwin built more than one thousand steam locomotives for the railroad.

Meanwhile, work continued on the tunnel. Railroad tunnel work was no job for the faint of heart. One journalist, afforded a tour of the Raton construction operation, reported climbing through a narrow opening at the south portal. Far into the darkness, he could see dimly twinkling candlelight and hear the steady clank of sledgehammers striking drills. Working in unison, the sledge men had to trust their partners as they each swung away in a regular rhythm. But the true hero was the holder of the drill. With each clang of a striking blow, the holder turned the drill a few degrees and trusted that the hammer to follow would be square and not come crashing down on his hands.

Once the drillers had done their work, dynamite was stuck in the holes and exploded to break down the rock face one foot at a time. Then the resulting debris was cleared, and another round of drilling began. On the north end, the rock in the Raton Tunnel was loose and crumbly, and the passage required substantial timbering, but on the south end, the bore was blasted through rock so solid that it needed no timbers. After the tunnel was opened to through traffic on September 7, 1879, the temporary system of switchbacks was abandoned.9

Regular operations over Raton Pass brought the Santa Fe squarely into the realm of mountain railroading. Gone were the easy grades of the plains. At high altitude, on steep hills and tight curves, in frequently harsh weather, everything was more difficult to do on mountain railroads. Brakes were just one example.

The locomotive was the beating heart of a train, but brakes were the circulatory system that allowed it to function. In the very early days of railroads, stopping a light train of one or two cars on a moderate grade was usually a matter of slowing down and then reversing the locomotive. As trains added more cars and heavier loads, individual cars were outfitted with brake wheels at one end. When these wheels were tightened, the connecting rigging clamped brake shoes against the running wheels and created enough friction to slow their revolutions, thus slowing the train.

Operating these brake wheels gave rise to the most dangerous job in railroading. At a whistle signal from the engineer, nimble brakemen ran atop the cars—jumping from one swaying car to another—and frantically set the brakes. Because it was frequently difficult to turn the brake wheel, even strong-armed brakemen carried a baseball bat–sized club of wood to give them more leverage. Hence, the term “club down the brakes.” When the train was past the downgrade, this process was reversed to release the brakes.

Railroad braking began to change in the 1870s when George Westinghouse patented the air brake. Operated from an air compressor on the locomotive, air pressure, rather than brawny arms, applied the force to press the brake shoes against the wheels. Initially, this was a straight-air system; that meant that if a coupling anywhere along the train became loose or blew out, the brake system for the entire train ceased to function. This either sent brakemen back atop the cars hurriedly setting brakes by hand or caused a runaway.

Westinghouse soon solved these straight-air problems by creating an automatic brake system. Each car was equipped with an air cylinder, and when the lines were full of air, the brakes were released; when air was bled off, the brakes engaged. Thus, should cars separate, the locomotive compressor lose pressure, or something else malfunction to reduce air pressure, the brakes would set automatically and in theory stop the train. But automatic air was not standard on the Santa Fe across Raton until 1885, and in the meantime, there were many instances of horrendous runaway wrecks.

Helper engines were the other mainstay and frequently the unsung heroes of mountain railroading. More correctly, the men who labored through heat and cold, wind and water, and a host of mechanical challenges to operate the helpers were the heroes. Depending on the route and their tonnage, trains were assigned helper engines to boost them over a divide. Once atop the hill, the helpers were disconnected and either dispatched back to their starting point or sent down the other side in front of the train to where they were needed next. Often a heavy freight would have the regular engine and a helper pulling in doubleheader fashion, with another helper or two pushing at the rear of the train. Sometimes longer trains were divided into sections for the pull over a pass.

All signals passed between the engineers of the helpers by whistle, and it took a great deal of coordination for three or four locomotives to move in tandem. More than one conductor and rear brakeman became nervous when watching a pounding helper locomotive pushing with all its might against their wooden caboose. The best they could hope was that the lead engines were indeed pulling upgrade and not suddenly backing down.

With the Santa Fe in command of Raton Pass, speculation was rampant about the railroad’s next move. The Colorado Weekly Chieftain of Pueblo reported quite assuredly that with the prize of Raton won, the Santa Fe would abandon its proposed line up the Arkansas River toward Leadville and “devote all of their resources and energies to the construction of their great transcontinental line.” Others thought that the Santa Fe was simply taking advantage of cheap Mexican labor “to play a game of bluff” at Raton and that the railroad’s true destination lay in the mountains of Colorado.

For his part, Rio Grande engineer McMurtrie, who had seen the Santa Fe’s determination in action, never believed that Raton was a bluff. McMurtrie bluntly told Palmer that the Rio Grande should either find a way to skirt its impasse at Raton or build south immediately from its La Veta branch in the San Luis Valley. McMurtrie was convinced that the Santa Fe would be across Raton Pass and en route to El Paso within the year.

In case McMurtrie was wrong and the Santa Fe was bluffing at Raton, Palmer incorporated a Colorado subsidiary to build from El Moro to the New Mexico line. But before any construction began, Palmer acknowledged that his little line had been both outfinanced and outfought. As McMurtrie later put it, there was no sense in pursuing a “cutthroat policy of building two roads into the same country when there was hardly business enough to support one.”10

But the overriding reason that Palmer did not press the Raton fight is that having wrestled control of Raton Pass away from the Rio Grande, William Barstow Strong and the Santa Fe were now threatening to deliver Palmer’s road a death knell by going for its jugular. Strong was indeed determined to extend the Santa Fe toward transcontinental destinations, but he was not about to give up the mining country of Colorado that looked all the more promising in the wake of the rich silver strikes at Leadville. What that meant was that the Denver and Rio Grande and the Santa Fe would soon be locked in a battle royal.