14

Battling for California

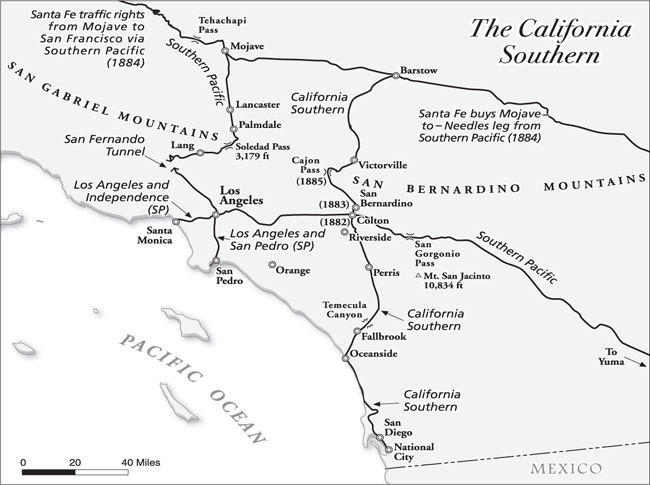

Having long heard the boasts of a chorus of railroad promoters, San Diego waited with increasing frustration to be connected to America’s growing railroad network. Tom Scott’s promise of the Texas and Pacific steaming into town was long dead. Huntington’s exit from the Los Angeles Basin at San Gorgonio Pass en route to Yuma with the Southern Pacific had been without so much as a glance in San Diego’s direction. General Rosecrans had trumpeted his California Southern as San Diego’s savior but then sold to the Big Four before laying a single rail. Still, there were plenty of San Diegans dreaming about railroads.

Remaining eager to attract a railroad at almost any cost, San Diego pledged six thousand acres of land and a mile of waterfront on San Diego Bay to any bona fide railroad venture. Local real estate developer Frank Kimball and his two brothers upped the ante by promising ten thousand additional acres and another mile of waterfront. Technically, the Kimballs were promoting their own interests at National City, a few miles south of Old Town San Diego, but any railroad would boost the prospects for both locations.

As this round of San Diego’s railroad boosterism gained momentum, the town found willing allies 100 miles to the north. San Bernardino was nestled in the foothills of the San Bernardino Mountains near the canyon leading to Cajon Pass. Here was yet another town seething over its treatment by a particular railroad and eagerly looking to ally itself with a competitor.

The Southern Pacific had bypassed San Bernardino in favor of Colton—named for the Big Four’s chief lieutenant—while en route to Yuma. The Big Four had also quashed the railroad dreams of Senator John P. Jones and the Los Angeles and Independence, but San Bernardino was still promoting the route over Cajon Pass. When railroad negotiations got serious again in San Diego in the fall of 1879, a committee of San Bernardino town fathers led by Fred T. Perris subscribed $40 to cover its travel expenses and made the pilgrimage south to lend its support.

This time, the railroad men meeting with local leaders were waving more than paper railroads. The interested parties proved to be none other than the same group of Boston investors who were so shrewdly backing the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe. The details took almost a year—during which time the Santa Fe resolved the Royal Gorge war and joined the Frisco in buying the Atlantic and Pacific.

Then in October 1880, the Boston crowd incorporated the California Southern Railroad Company—not to be confused with General Rosecrans’s earlier paper venture—and joined forces with the locals. They announced plans to build north from National City, pass through San Bernardino, and meet the Atlantic and Pacific, well, somewhere.

There was no better example of the Boston crowd’s commitment to Southern California and a western extension of its main line than the fact that Thomas Nickerson resigned the presidency of the Santa Fe to become president of the California Southern. As for Cajon Pass, no less an expert than the Santa Fe’s Ray Morley took a look at the canyon leading to the Mojave Desert and reportedly proclaimed, “This is nothing; we can go through here easily enough.”

Morley may have found the Cajon an easy passage, but his cost estimates for the line between National City and San Bernardino were another matter. Promoter Frank Kimball optimistically calculated construction costs for the 127-mile segment at $10,000 per mile; Morley’s estimate was $15,000 per mile. In a subscription circular, Nickerson reported the number as $18,000 but then provided for $25,000 per mile just to be safe.1

Huntington and his cohorts were adamantly opposed, of course, to any railroad other than their own building through Cajon Pass or reaching out to San Diego via any route. Huntington did not begrudge San Diego a railroad, but he meant to provide one himself in his own good time. The alliance of the locals with the Boston crowd signaled a substantial raising of the stakes.

As was usually the case, feisty Charley Crocker was blunt in urging Huntington to pull no punches when it came to the Santa Fe. “You could knock their securities a good deal below par through the newspapers,” he suggested to Huntington as the Santa Fe–financed California Southern gathered its forces.

Huntington no doubt appreciated his partner’s sentiments, but he needed little reminder that a Santa Fe–controlled line across California to San Diego would likely result in steamship service between there and San Francisco. Such a system would compete head-on with the Big Four’s Bay area monopoly.

If the Atlantic and Pacific or any other Santa Fe–backed venture could be held at the Colorado River or at least north of Cajon Pass, the California Southern—Boston dollars or not—would still be a line going nowhere except a connection with the Southern Pacific at Colton. Small wonder, then, that Crocker exhorted Huntington to “try and break them [the Boston crowd] down before they come into California.”2

Construction on the California Southern started north from National City in June 1881. The route connected with adjacent San Diego and then charged up the coast to Oceanside, cut inland to Fallbrook, and wound up Temecula Canyon. Here the Santa Margarita River cut a rocky defile through the Coast Ranges that at first glance seemed to promise no passage for a railroad. But San Bernardino’s Fred Perris, among the engineers surveying the route, was determined to keep the railroad bound for his town via as direct a route as possible. He ordered a line run along the canyon walls, above what a correspondent for Harper’s New Monthly magazine described as “a brawling stream.”

The local story handed down through the years is that one of the survey engineers—perhaps Perris or possibly chief engineer Joseph O. Osgood—asked an assistant to climb up and determine the high-water mark through the narrowest section of the gorge. More than halfway up the cliff, the man found a cluster of pinecones. Since no pine trees grew locally, the cones had clearly washed downstream from the higher mountains, and their lofty presence indicated that the canyon was susceptible to extremely high flash floods. When this fact was reported to the engineer, his response was a pompous “Nonsense,” and he “proceeded to plot what he considered to be the natural flood level of the canyon—some ten feet above the floor of the gorge.” Time would tell who was correct.3

Above Temecula Canyon lay the little town of Temecula, which had its roots in vestiges of Spanish land grants. From there, easier ground led north 40-some miles through a town named after Fred Perris and then to Colton. In many places—particularly Temecula Canyon—construction had been more difficult than expected, and President Nickerson was greatly annoyed when he saw that costs were taking every penny of $25,000 per mile and then some. Nickerson investigated, but by then it was too late.

For once construction had been first-rate. In fact, supervised by chief engineer Osgood, it had been too good. Osgood had spared no expense and built a first-class railroad along a route that by one report “promised inadequate traffic to support the investment.” Whether that pessimistic report—too good a railroad for too little traffic—held true would depend in part on the railroad’s ultimate connections.4

On August 21, 1882, the rails of the California Southern reached Colton, where the Southern Pacific’s main line lay across its path like a giant snake. The next step was to make a crossing of the Southern Pacific tracks by installing what in railroad parlance was called a “frog.” This was a specially designed crisscross of rails that permitted one railroad to pass across the track of another without derailing. The railroad seeking the crossing was responsible for the cost of installing the frog, and it could not interfere with the normal operations of the first line. The first line, however, was required by law to permit the crossing.

What actually happened at Colton was far more bizarre. The Southern Pacific had been doing its best to retard the California Southern’s northward construction through a variety of spurious writs and injunctions. These tactics continued at Colton when the Southern Pacific fenced off its tracks and denied the California Southern access to install its frog. The California Southern responded in kind and sought its own court order to force the Southern Pacific to permit the crossing. By the time this order was obtained—no small feat, considering the political influences of Huntington—almost a year had passed, and it was August of 1883.

California Southern engineer Fred Perris arranged for the construction of the Colton frog in the railroad’s shops at National City. Southern Pacific informants learned of its location, and the local sheriff seized the frog on yet another trumped-up charge. The sheriff then posted men to guard what was in effect the physical key to the California Southern continuing north to join the Santa Fe main line.

Perris was furious but bided his time. Proving that vigilance is required most when all seems the quietest, the sheriff took a nap just long enough for Perris and a crew to retake the frog, load it on a flatcar, and hurry it north. But simply securing the frog and putting it into operation across the Southern Pacific line were two different matters.

The California Southern’s onsite construction engineer at Colton, J. N. Victor, telegraphed the Southern Pacific’s assistant superintendent at Los Angeles that all was in readiness to effect a crossing once the Southern Pacific’s overland mail had passed. But as Victor led his crew forward, a Southern Pacific locomotive, tender, and gondola appeared and began a major demonstration of moving back and forth at the contemplated point of intersection. Word spread through the California Southern workers that twenty to thirty armed men were crouched inside the gondola just itching for a fight—shades of the Bat Masterson rumors on Raton Pass.

When the locomotive finally stopped and stood hissing steam at the proposed intersection, the fire alarm at nearby San Bernardino rang loudly to summon reinforcements for the California Southern. An excited crowd quickly gathered and demanded that the track be cleared. Tensions were so high on both sides that Victor thought it advisable to have the court order requiring the frog’s installation printed and served on each Southern Pacific employee.

The response was the time-honored “We don’t know anything about it,” and Victor had the order telegraphed to the sheriff of San Francisco to serve on the Southern Pacific’s corporate officers. Victor subsequently reported to California Southern president Thomas Nickerson, “It will probably cost us one to three hundred dollars; but I thought it the best thing to do.”

In the meantime, the local sheriff at Colton had organized an armed posse to enforce the court order and require the Southern Pacific track to be cleared whenever Victor gave the word. Victor, however, opted to be diplomatic. Because the California Southern had to use the Southern Pacific’s turntable and track and was on its depot grounds, Victor thought it “advisable to work here peaceably if possible.”

This approach resulted in begrudging overtures from the Southern Pacific crew. After some further posturing, all obstructions were removed, and both sides worked together to install the hotly contested frog that same afternoon. The Southern Pacific workers also agreed to release material for the California Southern extension to San Bernardino that had been held hostage in the Southern Pacific yards.5

With a truce called in the frog war, if not the greater corporate rivalry, the California Southern crossed the Southern Pacific line at Colton and laid tracks a few more miles into San Bernardino. It operated the first scheduled train into San Bernardino on September 13, 1883, just one month after the rails of the Southern Pacific and the Atlantic and Pacific joined at the Needles crossing of the Colorado River. This meant, of course, that there was still no access for the California Southern over Cajon Pass via any railroad, let alone a friendly one, and that left the California Southern at the mercy of the Southern Pacific, just as Huntington had planned.

“The Southern Pacific monopoly as completely ignores the existence of the ‘California Southern R. R.’ as though they had never heard of it,” grumbled a San Diego merchant; “they refuse to receive or deliver freight to or from it in spite of the law to the contrary.”

It didn’t help matters that in the early 1880s, the city of San Diego was less than a quarter the size of Los Angeles. The 1880 census showed a similar disparity between the surrounding counties: 33,381 in Los Angeles County versus 8,018 in San Diego County. Without a line of its own into the San Diego area, the Southern Pacific was doing all that it could to maintain or increase that disparity in favor of Los Angeles. When newcomers “find out how much it costs to get here,” the same San Diego merchant continued in despair, they “stop at Los Angeles.”6

San Diego and the California Southern were not alone in their frustrations. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe had long felt the hand of Huntington and the Southern Pacific—whether it was the brush-off handshake at Deming or the dilemma confronting the railroad at the Needles railhead of the Atlantic and Pacific. When one California newspaper learned that the Southern Pacific was building east from Mojave to confront this invader to the Golden State, it brashly predicted, “They [the Southern Pacific] are expected to gobble up the Atlantic and Pacific, scales, tails and fins.”

But William Barstow Strong and the Santa Fe had already proven their staying power. In theory under the Tripartite Agreement, the Southern Pacific was supposed to send shipments eastward over the Atlantic and Pacific, and one-quarter of those revenues were to service the interest on the Atlantic and Pacific’s bonds. It wasn’t nearly that smooth in practice. With the Central Pacific to the north and the Southern Pacific to the south, Huntington could be very choosy about how much traffic he allowed to flow eastward to Needles for the Atlantic and Pacific.

In the Santa Fe’s 1883 annual report, President Strong was forced to admit that while the company had completed another prosperous year, gross revenues remained on par with 1882. Despite the new connections with the Southern Pacific at Needles, Strong found himself reprising his report after joining the Southern Pacific at Deming: through traffic via the new connection had been very disappointing because Huntington was still directing the lion’s share either north over the Central Pacific or south over the Southern Pacific.

What California traffic the 35th parallel line did see was fraught with delays, bungled bills of lading, and misplaced freight cars. Even when California shippers specified a routing via the Southern Pacific–Atlantic and Pacific–Santa Fe line, “freight often became lost or delayed rather mysteriously between Needles and San Francisco.”7

Then disaster struck the newly completed California Southern. In December 1883 and January 1884, almost seven inches of rain fell at the Fallbrook weather station just downstream from normally arid Temecula Canyon. During February, rainfall of more than fifteen inches was recorded. The “brawling” Santa Margarita River through the gorge became a rising torrent. The man who found the pinecones had been right. The rushing water picked the track clean from its narrow perch and swept away bridges as if they were piles of kindling. San Diego learned the worst of the news on February 20, when passengers stranded by a rock slide near the southern end of the canyon walked into town.

To some, rebuilding the track in Temecula Canyon was a foregone conclusion. These included the Boston crowd, which footed the repair bill. To do otherwise would have abandoned their Southern California toehold and played right into Huntington’s hand. By late summer 1884, about one thousand men were at work in the canyon putting the rails and bridges right back where they had been. Others weren’t so sure about the decision. “Well,” mused one old-timer, “I have lived here a great many years and I don’t think you can ever put a railroad in that canyon which will stand.”

The line was finally reopened to through traffic between San Diego and San Bernardino on January 6, 1885, and San Diego’s ten-and-one-half-month isolation—after barely five months of rail service—was over.8

Meanwhile, the Atlantic and Pacific was hardly a road to nowhere, but given the freight situation along the Southern Pacific west of Needles, neither was it a paying concern. With the completion of a substantial and permanent bridge over the Colorado River at Needles in the summer of 1884, the Santa Fe faced one of those crossing-the-Rubicon moments that either make or break great corporations.

From whichever of its western termini the Santa Fe looked—Deming, Needles, or the Sonora Railway—the Southern Pacific in one manner or another acted as a sieve to filter its traffic and impact its rates. The Santa Fe could continue to operate as it was and attempt to extract some profit from the Atlantic and Pacific’s massive though largely undeveloped land grants. But that was hardly in keeping with William Barstow Strong’s mantra that a railroad must ever expand its markets and territories or die.

A second option for the Santa Fe was to abandon the Atlantic and Pacific line and retrench the railroad’s core business on the plains and in the Midwest. That, too, was untenable for Strong, although one might speculate which result of this option Strong feared most: Huntington’s taking advantage of the abandoned Atlantic and Pacific route and streaking into the Santa Fe’s stronghold of New Mexico, or Cyrus K. Holliday’s howl of indignation at abandoning the long-held Pacific dream. No, neither the status quo nor a retreat was an option to Strong. That left one other alternative: an all-out attack.

Leaving the Atlantic and Pacific as its unsteady subsidiary between Albuquerque and Needles, the Santa Fe proposed to strike west from Needles on its own and, if need be, parallel the entire route of the Southern Pacific for 600 miles from there to San Francisco. Huntington was far more concerned by this direct threat to San Francisco than he had been by the struggling efforts of the California Southern. But for once, the man whose partners had tried to rein him in at Yuma, had begged him not to throw out more branches, and had watched in awe as he juggled a myriad of complicated financings, was himself short of cash.

In part, this was because Huntington had great plans to join a number of eastern roads, including the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, to the Southern Pacific at New Orleans to make one single transcontinental line under his personal control. The complexities of Huntington’s plan in the East were mind boggling, but the ramifications in the West were simple and beneficial to the Santa Fe.

Huntington was never one to fight unnecessary battles, particularly on multiple fronts. His need for cash became even more desperate after the country’s financial markets suffered a sharp downturn. The result was that Huntington sat down with William Barstow Strong—just as he had years before with Tom Scott and later with Jay Gould—and hammered out another compromise.

First, the Atlantic and Pacific bought the recently completed 242-mile Southern Pacific line between Mojave and Needles for $30,000 per mile on what was technically an extended lease-purchase. This was almost the same as selling the line to the Santa Fe, but perhaps Huntington’s ego required that he preserve the fiction of the Atlantic and Pacific as an independent. Huntington’s own influence in the Atlantic and Pacific disappeared when he sold his shares in the Frisco about the same time as part of his marshaling of cash.

Second, Huntington granted what once would have been unthinkable. The Southern Pacific gave the Atlantic and Pacific trackage rights between Mojave and San Francisco Bay via its San Joaquin line over Tehachapi Pass for an annual rental of $1,200 per mile, if the Atlantic and Pacific chose to use it. It also offered terminal facilities in Oakland and San Francisco. Both of these provisions were acknowledged to be assignable to either the Santa Fe or the Frisco should it become successor to the Atlantic and Pacific—a likely prospect even then.

But what was Huntington getting out of this besides cash? The answer was even more cash. The Santa Fe and the Frisco agreed to purchase $3 million of Atlantic and Pacific bonds of dubious marketability that were held by the Southern Pacific. Huntington’s Pacific Improvement Company had bought the bonds at 50 percent of par when it was constructing the Mojave-Needles line, and now Huntington was glad to cash them out for the same amount.9

The Huntington-Strong agreement became operational on October 1, 1884, and Atlantic and Pacific trains could steam across the bridge at Needles and climb across the ranges of the Mojave Desert to the Southern Pacific line at Mojave. That left an 80-some-mile section between the Atlantic and Pacific’s Mojave line and the railhead of the California Southern at San Bernardino. In between lay Cajon Pass.

Ten years before, Huntington’s surveyors had faced off here against the men of the Los Angeles and Independence. Now, with perhaps a sigh of the inevitable, the Southern Pacific did not contest the route, as Santa Fe surveyors worked upgrade from the Mojave flats and hacked a line through the piñons and junipers to Cajon’s summit. Much of the grade on the southern side had already been staked in anticipation of the California Southern’s extension from San Bernardino.

Once work crews repaired the flood damage in Temecula Canyon, they were dispatched north to Cajon Pass in January 1885. Many were veteran Chinese laborers; others were Mexican graders who had been working on the Santa Fe’s Sonora Railroad. Work was slow, and the uphill grade out of San Bernardino reached 2.2 percent. Here, too, the floods of the previous year had sent torrents of water down the canyon. Paying closer attention to the high water line this time, construction engineer Fred Perris moved the originally surveyed route to higher ground above normally dry Cajon Creek Wash.

By July 19, the right-of-way was graded as far as Cajon Station, about 5 miles from the 3,775-foot summit of the pass. Around what much later came to be called Sullivan’s Curve and along Stein’s Hill, the grade climbed at 3 percent. Just above Pine Lodge, the mouth of the tunnel that the Los Angeles and Independence had started in 1874 was choked with bushes and rockfall. Perris opted to avoid tunneling and instead dug out a series of deep cuts as the line climbed the final miles to the summit.

Meanwhile, another crew was working south from a little station called Waterman on what was now the Atlantic and Pacific’s Mojave line. Westbound toward Cajon Pass, the grades were easier. The rails were joined on November 9, 1885, just below the summit on the south side, but the ensuing celebrations were not without another test of nature. Perris had moved the grade above the high-water line along Cajon Creek Wash, but he had failed to design culverts for the runoff streams that gushed down the smooth side canyons and pooled alongside the fills and embankments. The deep cuts posed a similar hazard and spewed mud onto the tracks before they were properly supported with a framework constructed from timber, or cribbed.

These problems were soon corrected and the obstacles overcome. In fact, the Santa Fe installed a modified version of the snowshed through some of the deeper cuts. Terraced hillsides were roofed over with wooden structures that angled outward from the center to channel runoff water to the ends of the cut and prevent it from falling directly onto the tracks.10

Even as this construction across Cajon Pass was completed late in 1885, William Barstow Strong had his share of critics among the normally loyal Boston press. Strong was criticized for having paid too much for the Mojave line. Some said that its very acquisition had been Huntington’s cagey way of blunting the Santa Fe’s drive to build an independent line to San Francisco. Still others found fault with Strong’s rescue of the flooded California Southern. But in the battle for California—which was far from over—one name would in time seem prophetic. The little way station of Waterman, where the Cajon Pass route now cut south from the Mojave line, was renamed not Potter for Huntington’s middle name, but Barstow in honor of Strong’s.11

Meanwhile, San Diego waited expectantly for regular train service to commence. The San Diego Union could barely contain its enthusiasm: “San Diego is out in the highway of the world’s activity to-day,” an editorial proclaimed, “and needs to make haste to take her position in the onward march. It is an era of new ideas, new methods, new enterprises and new men. It is the day of the nimble dime rather than of the slow dollar. Old fogyism must go to the rear.”

The first through train to the east pulled out of San Diego on November 16, 1885. The town paraded a little band for its send-off, but the real celebration was at San Bernardino. There the town turned out en masse to speed the train over Cajon Pass and cheer its place on what was at last a transcontinental line through California controlled by parties other than the Big Four.

Ten days later, the first through Pullman from Kansas City steamed into San Diego, and the San Diego Union predicted in far more tempered tones that the city would enjoy “a period of moderate expansion.” What had happened to cool its ardor? The answer: stark economic reality.

Huntington, having lost his bid to hold the Santa Fe at Needles because of a need for cash, now sought to parry its further extension beyond the California Southern by granting it trackage rights into Los Angeles. For the same annual rental terms that he had just extended for the line into San Francisco, Huntington gave the Santa Fe the right to operate trains on the 54-mile Southern Pacific line between Colton and downtown Los Angeles. Suddenly Santa Fe traffic descending Cajon Pass into San Bernardino could either proceed directly west to Los Angeles and its port of San Pedro or follow the California Southern line south to San Diego through tempestuous Temecula Canyon.12

San Diego was outraged even as it cheered the arrival of its first transcontinental train. Three days later, the first Santa Fe train operated over the Colton line into Los Angeles, which could now boast of not one but two transcontinental connections. It was a reminder that San Diego’s own battle with its California neighbors was far from over, its own future far from resolved.

To the Santa Fe, San Diego had long been an important piece on the western chessboard, but the game itself was still San Francisco. With trackage rights down the San Joaquin Valley and now also into Los Angeles—and less than booming business in San Diego—the Santa Fe relegated the California Southern to a branch line, not the terminus of a great transcontinental system.

“San Diego should have anticipated from the very start,” the Los Angeles Times lectured, “that this new overland system would make San Francisco its ultimate objective point.” Recognizing its own town’s secondary status, the Times freely admitted, “San Francisco is the Rome of the Pacific Coast: all roads lead to it.”

And when it came to betting between Los Angeles and San Diego, the choice for the Santa Fe was equally clear. “It doesn’t stand to reason,” a Santa Fe official confessed somewhat apologetically, “that the road can afford to put those little merchants [in San Diego], who have only two or three straight carloads of through freight in a year, on the same footing with men here who have as much in a week… Los Angeles is our natural and inevitable western terminus.”13

William Barstow Strong had his own take on the matter. It had, in fact, been purely economic. “Railroading is a business wherein progress is absolutely necessary,” he told his shareholders. “A railroad cannot stand still. It must either get or give business; it must make new combinations, open new territory, and secure new traffic.”14

If the battle for California was only about access into the state’s markets, the Santa Fe had clearly won. But that did not mean that the war between the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe was over. At the same time, on its eastern flank, the Santa Fe would have to face Jay Gould again.