22

Top of the Heap

As the map of the American West was filled in, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway patiently yet firmly continued its growth. In the summer of 1902, Edward Payson Ripley cast an expansionist eye southeast from Phoenix toward the Southern Pacific line at Benson. He also looked north from the Santa Fe’s new terminal at Oakland into the timberlands of northern California. E. H. Harriman and the Union Pacific were not pleased by the challenge on either front. If the Santa Fe kept expanding, it might connect to its Deming stub or parallel the Southern Pacific all the way north to Portland, Oregon.

In Arizona, the Santa Fe and the Southern Pacific had long acted in relative harmony. The Southern Pacific held sway across the southern part of the territory, and the Santa Fe did likewise in the north. In between, the sleepy little town of Phoenix didn’t attract much attention, although the Southern Pacific had promoted a branch from its main line at Maricopa by 1887 and gone to some lengths to discourage other competitors.

In the northern part of the territory, scarcely had the Santa Fe–backed Atlantic and Pacific built west from Flagstaff than town fathers from the territorial capital of Prescott lobbied for a branch extension south to their town. When the Atlantic and Pacific showed no inclination to undertake the route, local interests incorporated the narrow gauge Prescott and Arizona Central Railway and built between Prescott and the main line at Seligman in 1887. The terrain was tough, the road’s equipment second rate, and the service anything but regular.

Consequently, in 1889, the Santa Fe looked to the feasibility of a 57-mile standard gauge route from the main line at Ash Fork to Prescott that would also serve nearby copper mines and could logically be extended to Phoenix. Named the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railroad, this Santa Fe ally opened to Prescott in 1893 and continued to Phoenix by 1895. It was nicknamed the “Pea Vine” route because of its tight spirals and curves. According to one oft-told joke, a locomotive engineer could pass his tobacco plug to the rear brakeman on the hairpin curves.

After Ripley acquired the Pea Vine line outright for the Santa Fe in 1901, he immediately ordered major track and grade improvements along the route. By then, what concerned E. H. Harriman were Ripley’s intentions southeast of Phoenix.1

Ripley was backing another local line called the Phoenix and Eastern Railroad. It ran southeast from Phoenix up the Gila River and proposed continuing up the San Pedro River to the Southern Pacific main line at Benson. On the surface, it seemed like a rather innocuous threat to the Southern Pacific.

But in an era when many western railroads were contemplating cutoffs to shorten their original lines, Harriman was toying with a Southern Pacific cutoff between Lordsburg and Yuma that would run along the Gila River, put Phoenix on the main line, and save both mileage and heavy grades. Tucson didn’t think much of the idea, of course, but Harriman saw it as his prerogative.

Harriman also saw southern Arizona as a Southern Pacific fiefdom and strenuously objected to the Santa Fe’s incursion. The threat wasn’t so much a Santa Fe–backed connection at Benson, but rather the line continuing up the Gila and connecting with the Santa Fe stub that had ended so ingloriously at Deming in 1881. This would cut through the heart of southeastern Arizona and flirt with the copper mines at Clifton and Morenci.

In December 1903, Phoenix and Eastern grading crews building east crossed to the north bank of the Gila just west of Kelvin. This move gave every appearance that rather than following the San Pedro upstream to Benson, the Santa Fe–backed effort was intent on pushing straight through the Gila Canyon toward Deming. Harriman saw red. He immediately dispatched his own survey crews to contest the narrow canyon where Phoenix and Eastern surveyors were already pounding stakes beneath rocky walls that in some places towered hundreds of feet above the river.

Once again, opposing forces fought for a strategic passage. Rival surveyors rushed competing lines that overlapped each other almost every step of the way. Grading crews close behind added to the frenzy by blasting rock onto each other’s staked line. And journalists filled their columns with descriptions reminiscent of the Royal Gorge war.2

Meanwhile, northern California was no less hotly contested, if without quite the drama of the Gila Canyon. When Ripley attempted to acquire the California and Northwestern Railroad in the summer of 1902, Harriman beat him to it. Harriman considered any Santa Fe expansion north of San Francisco to be in the same vein as the Phoenix maneuver. In no uncertain terms, Harriman told the Santa Fe that he was adamantly opposed to it. Ripley acquired the little Eel River and Eureka Railroad instead and showed no sign of backing down.

Harriman focused again on the Arizona situation and repeated his demand that the Santa Fe sell him the Phoenix and Eastern and abandon its route. Ripley once again carefully studied the map of the West. The truth of the matter was that the Gila Canyon was a tortuous route. With serpentine meanders and tight passages, it was never going to be a major speedway. But perhaps Ripley could use Harriman’s angst about it to leverage the Santa Fe’s more strategic goals. Ripley shrewdly replied to Harriman that the Santa Fe would drop its expansion up the Gila River, but only as part of a broader settlement of competing interests in northern California.

Initially, Harriman scoffed at the offer, but after considerable negotiation, he agreed to a compromise. It provided for the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe to own the competing lines in northern California jointly. In return, Harriman got the Phoenix and Eastern and the lion’s share of the press.

But if there is any opinion as to who won and who lost this fight, it should be noted that the Southern Pacific main line never pierced the Gila Canyon. It continues to run on generally its original route between Lordsburg and Yuma. The Santa Fe, on the other hand, enjoyed future growth in the Pacific Northwest, and connections there eventually helped to facilitate the road’s merger with the Burlington Northern Railroad in 1995.3

The Ripley team undertook another strategic decision during this time without trouble from competitors. Despite the Santa Fe’s integrated system, there was still one section in the Los Angeles-to-Chicago corridor that posed a major operational bottleneck. The steep grades of Raton Pass limited the size of trains, required costly helper engine operations, and slowed through operations on the single track. Conditions weren’t much better climbing out of the Rio Grande Valley over Glorieta Pass.

William Jackson Palmer had recognized the problem as early as his 1867 survey for the Kansas Pacific. Palmer’s alternative had been to avoid the Raton Mountains and roughly follow the main branch of the Santa Fe Trail from the headwaters of the Cimarron River to Las Vegas, New Mexico. Even if this Cimarron line was “not adopted at first,” Palmer had written presciently in 1867, “it must be built eventually, to economize the transportation of through passenger and freight traffic” [his italics].

By 1902, Edward Payson Ripley had agreed and determined to build a cutoff for east-west freight operations that would bypass both Raton and Glorieta passes. To do so required a line well south of Raton and smack in the middle of New Mexico, but this was to have numerous advantages.

Santa Fe was never on the railroad’s main line, and the town’s branch traffic consisted increasingly of destination passengers. Even Albuquerque was not a large freight market. Bypassing both towns with transcontinental freight traffic would speed operations at no loss to local markets. So the railroad looked south of Albuquerque for a route that offered low grades and plenty of straightaways.

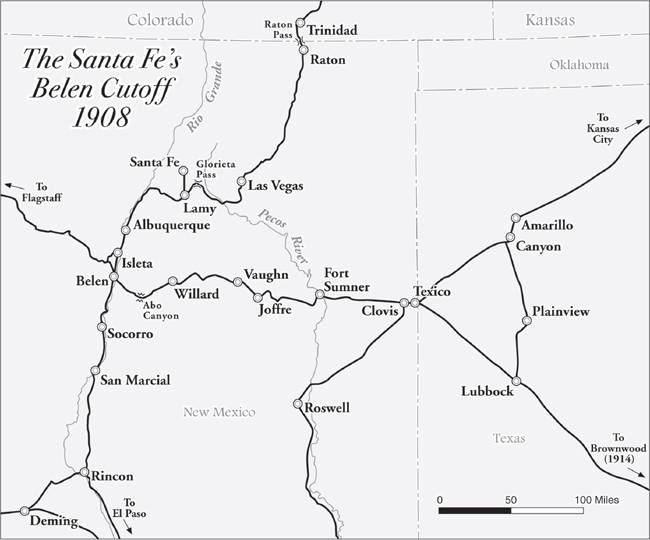

Surveyors took to the field in the spring of 1902 and soon pinpointed Abo Canyon, about 50 miles south of Albuquerque, as the low-angle gateway from the Rio Grande Valley to the broad expanses of eastern New Mexico. Engineers picked Belen on the Albuquerque-to-El Paso line as the jumping-off point. In a short time, Belen would become the busiest railroad junction in New Mexico.

The new cutoff ran southeast from Belen, up Abo Canyon, and topped out at 6,535 feet at a station named Mountainair. This was only 1,100 feet lower than the elevation at the Raton Tunnel, but the difference in grades was startling. The maximum gradient at Raton Pass was 184.8 feet per mile. The new Belen Cutoff had a maximum gradient of 66 feet per mile in Abo Canyon and half that along the rest of the route as it ran east to Vaughn, Fort Sumner, and Clovis.

Just inside the Texas border at Texico, the strategic genius of this tactical effort to reduce costs showed itself. Northeast from tiny Texico, the Santa Fe built on to Amarillo and its Southern Kansas Railway subsidiary. This, of course, led straight to the Santa Fe’s Kansas main line. The roadbed and tracks of the Southern Kansas were quickly rebuilt to handle the increased volume of traffic.

When the construction dust settled, the mileage over Raton Pass versus Abo Canyon was almost identical, but the gradients made all the difference. The California Limited and later passenger trains usually still operated over Raton Pass, providing service to Las Vegas, Santa Fe, and Albuquerque, but if the question was heavy freight for transcontinental service, the route led through Abo Canyon and over the Belen Cutoff.

The Belen Cutoff became operational on July 1, 1908. But even before its completion, the Santa Fe undertook surveys on the second leg of its strategic Y at Texico. This leg led southeast through Lubbock to hook up with the old Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe. By the time it was completed in 1914, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe had finally rid itself of the coolness of the handshake that it had received from the Southern Pacific at Deming in 1881.

The new direct route of the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe across Texas, over the Belen cutoff, and west to California cut the distance over the Santa Fe from Galveston to San Francisco from 2,666 miles to 2,192 miles and to Los Angeles from 2,355 to 1,881 miles. Regardless of the strengths of the Southern Pacific, the Santa Fe had made itself a key player not only in the California-to-Chicago markets, but in the California-to-Gulf Coast markets as well.4

At the macro level, it was Edward Payson Ripley’s strategic expansions and his determined focus on solid infrastructure, rolling stock, and personnel that pushed the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe to the top of the heap. But beneath this corporate saga, there are two stories that underscore what the railroad came to mean to the American Southwest.

As Fred Harvey’s Harvey Houses made the transition from overnight stay to destination resort, scenic locales and cultural enclaves along the Santa Fe’s main line became increasingly popular and figured prominently in the railroad’s marketing plans. These locations included the mountain air and mineral springs of Las Vegas, New Mexico; the special allure of Santa Fe; and the respite of California’s sun and surf.

But none could match the grandeur and breathtaking majesty of the Grand Canyon. While railroad tracks would never wind through the canyon’s serpentine length, here at one of the scenic wonders of the world, the Santa Fe Railway, the Fred Harvey Company, and a diminutive but determined woman would join forces to tie the Santa Fe inexorably to the landscape it traversed.

Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter was born in Pittsburgh to Irish parents in 1869. Her father operated millinery and furniture businesses, and the family’s moves took them to Texas and Colorado before they settled in St. Paul in 1880. Mary showed early signs of being a gifted artist, and she begged her father to attend an art school. Her dream was realized at the California School of Design—later named the San Francisco Art Institute—and she graduated with a four-year degree in art and design as well as her teaching credentials.

During her academic program, Colter also apprenticed in a local architect’s office. At the time, there were only about eleven thousand architects in the United States, and California did not even have a licensing requirement. Women in the profession were rare, and after graduation in 1892, Colter returned to St. Paul and began a fifteen-year career teaching art. But there were to be interludes.

On a return visit to San Francisco, Colter found one of her friends working at a Fred Harvey establishment. She happened to strike up a conversation with the manager and expressed an interest in working for the company as it expanded its operations to include gift shops and newsstands. Nothing came of the encounter immediately, but it is a testament to the Harvey system of scouting out talent that the manager reported Colter’s name and her credentials up the Harvey chain of command.

By 1902, the Fred Harvey Company—absent its founder, who had died the preceding year—was completing one of the jewels of its budding system: the Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque. Surrounded by quiet courtyards, sweeping lawns, and brick pathways, the hotel boasted seventy-five guest rooms, pleasant parlors, and spacious dining rooms to be run to the very best of Fred Harvey standards. The Alvarado was connected to the Santa Fe depot by a two-hundred-foot arcade, and the stucco exterior of both structures resembled the historical Spanish mission architecture of the Southwest rather than the European influences of so many recent buildings.

As part of its plan to emphasize the cultures of the Southwest, the Fred Harvey Company proposed to build an “Indian building” along the arcade adjacent to the Alvarado. It would both showcase Native American artifacts and provide a sales outlet for contemporary arts and crafts. What the company needed to perfect the plan was “a decorator who knew Indian things and had imagination.” When Mary Colter received a lengthy telegram asking if she was the right person, she hurried to Albuquerque and began a forty-year association with both the Fred Harvey Company and the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe.

The importance of Mary Jane Colter’s initial contribution at the Alvarado to Southwest architecture cannot be overstated. As an advertisement for the hotel boasted that summer, the Alvarado was “the first building in New Mexico to revive the Spanish tradition and thereby make the whole Southwest history-conscious.” Colter’s role was to provide the vehicle—part museum, part shop—to make that culture readily accessible to the thousands upon thousands of passengers who passed through the region on the Santa Fe’s trains.

When her assignment at the Alvarado was complete, Colter returned to St. Paul to continue teaching, but two years later, the Fred Harvey Company summoned her to the rim of the Grand Canyon to undertake a bigger venture. In 1901 the Santa Fe had acquired an old mining railroad and extended its tracks from a copper mine at Anita to the South Rim. It was only 65 miles from Williams on the Santa Fe’s main line to the canyon, and easier access meant more visitors.

The Fred Harvey Company quickly determined that more visitors required overnight accommodations, so the architect of the Alvarado, Charles F. Whittlesey of Chicago, was engaged to design the fabled El Tovar Hotel near the railroad’s terminus. For some reason, despite his experience at Albuquerque, Whittlesey chose to design El Tovar in the chalet style of the great resort hotels of Europe. But Mary Colter was commissioned to design the adjacent “Indian building,” to be called Hopi House, and all subsequent structures on the rim would follow her architectural lead.

Designed after a traditional Hopi dwelling, Hopi House again combined a museum for Native American rugs, baskets, and other artifacts, with a sales area for contemporary crafts. Hopi and Navajo artisans frequently worked on site to make jewelry, baskets, blankets, and other sales items. Both Hopi House and El Tovar opened to rave reviews in 1905.

Among early visitors was artist Thomas Moran, who came at the request of the Fred Harvey Company and produced a series of landscapes that captured the special beauty and sweeping magnitude of the canyon. Moran’s works did much to publicize the Grand Canyon, and that was good for business, selling both Santa Fe passenger tickets and Fred Harvey meals and beds.

Once again, Mary Colter returned to St. Paul to teach, but finally Fred Harvey hired her full-time as an architect and designer to oversee the company’s expanding facilities. Technically, she worked for Fred Harvey, but a portion of her salary was paid by the Santa Fe under the continuing arrangement that Mr. Harvey had first proposed to the railroad in 1876: Fred Harvey operated the restaurants and hotels and owned the furnishings, but the Santa Fe owned the buildings and land.

Colter’s first full-time project was the interior decoration of the El Ortiz at Lamy, New Mexico. By Harvey House standards, El Ortiz was small—fewer than ten rooms—but it was the perfect gateway to Santa Fe. No less a western authority than Owen Wister, author of The Virginian, described El Ortiz as a temptation “to give up all plans and stay a week for the pleasure of living and resting in such a place.”

Then it was back to the Grand Canyon to design Hermit’s Rest. The Fred Harvey Company had constructed a road for tours west along the South Rim and needed a place for shelter, refreshments, and, of course, the requisite souvenirs. With its haphazard stonework, a stout bear trap out front, a huge stone fireplace, and a crude interior, the building indeed looked like the den of a hermit—exactly what Colter intended.

Hermit’s Rest and the Lookout Studio on the rim just west of El Tovar were both completed in 1914. After the interruption of World War I, Grand Canyon National Park was established in 1919, and Mary Jane Colter went on to design the facilities at Phantom Ranch, the Watchtower at Desert View, and Bright Angel Lodge. Before her career was complete, Colter’s influence would be felt up and down the Santa Fe line, from the interior of La Fonda at Santa Fe to La Posada at Winslow, Arizona, for which she was both architect and decorator.

“Her buildings,” wrote biographer Virginia Grattan, “fit their setting because they grew out of the history of the land. They belonged.” And because the Santa Fe also embraced this history with its train names, décor, and advertising, it too belonged. Perhaps no other railroad became as closely associated with the landscape it traversed as did the Santa Fe across the American Southwest.5

But if there was no doubt that the Santa Fe belonged to the land it served, could it truly deliver the goods? It needed a public relations exclamation point, and it got one. In early July 1905, a showboating cowboy with the moniker “Death Valley Scotty” swaggered into the Santa Fe’s Los Angeles depot and flashed a roll of bills. Chicago, fast as can be done, he ordered.

It quickly became a publicity stunt—indeed, Scotty appears to have intended it that way from the start—but the fact that the Santa Fe obliged was proof that it had emerged at the top of the heap as America’s greatest transcontinental line. Soon the jingle “Santa Fe All the Way” would become more than a marketing slogan and attest to the railroad’s transcontinental racetrack.

Walter Edward Scott was one of those people who, through a mix of charm, humor, and congenial deception, surrounded himself with a veil of mystery that confounds any attempt to tell his story. Part of the problem is that Scotty himself was one of the biggest storytellers of them all.

He was born in Kentucky in 1872. His father was a harness-horse trainer and breeder, and young Scott developed an early ease with horses and mules. As early as 1884, he left home for the West to join older brothers who were working as cowboys. Reports have Scott working as a water boy on the California-Nevada boundary survey and as a helper on the famed twenty-mule teams of the Harmony Borax Works in Death Valley.

About 1890, Buffalo Bill Cody hired Scott for his Wild West Show. Somewhere along the line, Scotty—by then, no one was calling him Walter—took on the moniker Death Valley Scotty. He worked the show for twelve seasons before quitting after a reported dispute with Cody. In the interim, it’s likely that Scott used at least some of his off-seasons to return periodically to Death Valley. He also seems to have spent two winters working in gold mines near Cripple Creek, Colorado.

By the time Scott left Cody’s Wild West Show in 1902, one of the last chapters of the American mining frontier was being played out in and around his old stomping grounds. The Nevada towns of Tonopah, Goldfield, and Rhyolite all hoped to rival Leadville or Tombstone, not with silver but with gold, and no one was at all certain what riches might lie hidden in Death Valley’s rocky ravines.

First and foremost, Scott was a promoter. He flashed two souvenir nuggets that his wife, Ella, had gotten from a Colorado gold mine and spun a story of riches hidden in a location in Death Valley known only to him. He then parlayed this tale into a grubstake from a New York banker named Julian Gerard.

Scott alternated his time between Los Angeles and Death Valley but did not develop his purported mining property. Instead he lived the life of a high roller and spent Gerard’s cash as his own, all the while asserting that his newfound wealth came from his fabulous, hidden mine. This charade went on for the better part of two years before Scott approached a Chicago businessman for a similar grubstake.

Aside from sharing 1872 as their birth year, Albert M. Johnson was the polar opposite of Walter Scott. Born in Oberlin, Ohio, Johnson was the son of a wealthy banker and businessman. He graduated from Cornell University in 1895 with a civil engineering degree and married a Cornell classmate, Bessilyn “Bessie” Penniman, the following year. Johnson worked for his father in the family businesses until a tragic railroad accident on a Denver and Rio Grande train near Salida, Colorado, in December 1899 killed his father and left Johnson with a spinal injury that caused him chronic back pain and some paralysis the rest of his life.

In 1902 Johnson and his father’s former business partner, Edward A. Shedd, bought the National Life Insurance Company of Chicago at foreclosure. Johnson eventually increased his holdings to 90 percent of the ownership. Sometime in 1904, Johnson met either a man fronting for Scott or Scott himself and heard the now well-worn tale of Scott’s Death Valley riches.

Having made a considerable profit from a lead-zinc mine in Missouri, Johnson was willing to take a chance on Scotty. But given their future relationship, it must also be speculated that something clicked between the two men. The following year, probably with funds provided by Johnson, and quite likely in an attempt to impress Johnson with the success of his Death Valley venture, Walter Scott swaggered into the Los Angeles office of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe and made his simple but profound request: “Chicago, fast as you can do it.”6

Supposedly, Scott suggested that his goal was a time of forty-six hours. If so, that was a full day faster than the schedule of the California Limited and twelve hours faster than the existing Los Angeles-to-Chicago record. That eastbound record over the Santa Fe was held by a special train called the Peacock Special that made the run in fifty-seven hours and fifty-six minutes in March 1900, carrying the vice president of the Carnegie Steel and Iron Company, Alexander R. Peacock, on his way to Pittsburgh for an urgent board meeting.

Later there would be ample speculation whether Scott was just plain crazy, whether he had indeed peeled off $5,500 in big bills to pay for the excursion, or whether the Santa Fe was somehow involved as a coconspirator in a publicity stunt. Certainly the railroad gave its all for the run.

What is fact is that on the afternoon of Sunday, July 9, 1905, Walter and Ella Scott arrived at La Grande Station in Los Angeles and stepped aboard a train that would quickly come to be called “the Scott Special,” or with the hyperbole of hindsight, “the Coyote Special.” Engine no. 442 was to start the journey and pull a consist of one baggage car, one dining car, and one standard Pullman, the Muskegon.

Eastbound to San Bernardino the special roared, pausing only long enough to pick up a helper for the climb over Cajon Pass. At the summit, “the helper engine was uncoupled on the fly and, while the speed of the train never slackened for an instant,” the helper engine raced ahead and darted onto a siding. The switch to the main line was then closed, and the oncoming special sped past without so much as a hint of slowing.

East of Cajon, Scott’s special flashed downgrade to Barstow at more than a mile a minute. The problem here, Frank Holman, a reporter on the train recalled, “was not how fast we could run, but how fast we dared to run.” Reportedly, the distance between mileposts 44 and 43 went by in 39 seconds—96 miles per hour.

At Barstow came the first change of crews and locomotives. Then it was on to the Colorado River at Needles and a Sunday evening arrival just six hours and seventeen minutes after leaving Los Angeles. After another crew and locomotive change—there would be nineteen engines and engineers used in all—the special roared across the river on the steel cantilever bridge south of Needles that had replaced the early wooden structure opposite town.

Dinner was served in the dining car—to Fred Harvey standards, of course—despite the rocketing motion of the train. By the time the newspapers got ahold of the story, the menu was reported to have featured a “Caviare Sandwich à la Death Valley” and a juicy, two-inch-thick “Porterhouse Steak à la Coyote.”

Meanwhile, northern Arizona flew by outside the windows as the train climbed up and down the heavy grades below the San Francisco Peaks and rushed on eastward in the darkness across Cañon Diablo, past Gallup, and on into Albuquerque. North of Albuquerque at Lamy another helper was put on for the climb over Glorieta Pass. Even across Glorieta and Raton, the Scott special averaged just over forty-six miles per hour—quite a record, considering the tough mountain railroading involved.

By the time the train raced into La Junta, Colorado, the mountains were behind it, and up ahead the Santa Fe’s raceway across the plains of Kansas and into the heartland urged even greater speeds. From Dodge City, Scotty sent President Theodore Roosevelt a telegram: “An American cowboy is coming East on a special train faster than any cowpuncher ever rode before; how much shall I break transcontinental record?”

East of Dodge City, a continuing succession of men and equipment sped the Coyote Special through the darkness of a second night. Josiah Gossard, a Santa Fe veteran with twenty years’ experience as a road engineer, took the throttle for the run between Emporia and Argentine, just short of Kansas City. Notwithstanding four slow orders, Gossard covered 124 miles in 130 minutes, the fastest time yet recorded between those two points.

Shortly before eight in the morning on Tuesday, the train thundered across the big steel bridge across the Mississippi, just south of Fort Madison, Iowa, and charged down A. A. Robinson’s straightaway toward Chicago. The 105 miles between the river and Chillicothe flew by in 101 minutes. One report claimed that the special bore down on Dearborn Station doing 60 miles an hour.

At six minutes before noon on Tuesday, July 11, 1905, Death Valley Scotty’s special came to a halt outside the station. The train had covered 2,265 miles in just 44 hours and 54 minutes—an average, including all delays, of 50.4 miles per hour.

It’s hard to say who was more elated—Scotty or the Santa Fe’s public relations department. Scott no doubt called on Albert Johnson, but the Santa Fe had a story that it would tell up and down the line and across the country. The special had been given the right-of-way across the country—even the vaunted California Limited was sidetracked for it—but otherwise, no extraordinary provisions had been made. The run was completed with regular equipment and standard crews.

“I’m buying speed” was the pithy quote attributed to Scott, but the Santa Fe copywriters put a good deal more spin on it. “The value of a whirlwind run,” the Santa Fe rationalized, “lies in the fact that such spurts thoroughly put to test the track, the engines, and the operating force. They demonstrate to the world of travel that the regular hurry-up schedule can be easily maintained the year round; that the track is solid and dependable; that the engines are powerful and swift; also that the men on and behind the engines and along the track are keen of eye, clear-brained, and quick to act.”7

A few years after this publicity stunt, Albert Johnson finally decided that he should visit Death Valley and see firsthand how Walter Scott had been spending his money. What he discovered surprised him. There was no sign of a gold mine, of course, but Johnson found himself invigorated by the dry heat and stark beauty of Death Valley. He returned again and again and spent weeks on end poking around its canyons with Scott. He “loves a good time and is a high roller,” Johnson admitted of Scotty, but, said Johnson, Scott was “absolutely reliable, and I don’t know of any man in the world that I would rather go on a camping trip with than Scott.”

By the 1920s, Death Valley Scotty was a national legend, and Scotty’s Castle, a huge estate of Moorish architecture, was taking shape in Grapevine Canyon, fueled by Scotty’s lost mine stories and in truth financed by Johnson’s millions. Did Johnson care? “Scott repays me in laughs,” Johnson is reported to have said.8

Johnson’s wife, Bessie, was killed in an automobile crash in Death Valley in 1943. Johnson passed away in 1948. Death Valley Scotty told tales of his secret mine until his end on January 5, 1954. Scott is buried on a hill above the castle that Albert Johnson graciously let him call his. It later became part of Death Valley National Park.

The 1905 ride of the Scott special was a flash in the pan of railroad hype and hoopla, but it called undeniable attention to the railroad system that Colonel Holliday’s little line had become. Santa Fe mileage had grown from 6,444 miles in 1897 to 9,527 in 1906—an increase of nearly 48 percent. Gross earnings during this same period had climbed from $30 million to $81 million, resulting in a net income of $18 million in 1906 as opposed to zero nine years earlier.

But Edward Payson Ripley was far from finished. In his annual report for 1906—echoing the refrain of William Barstow Strong that a company could not afford not to build—Ripley announced that despite recent expansions and acquisitions, it would be necessary to continue such an expansionist policy for an indefinite period of time. “The country served by the System is growing so rapidly that a large amount of additional equipment and of other facilities for the transaction of business must be provided.”9

Ripley might have added that the country served by the Santa Fe was in fact growing so fast because of the railroad and that the Santa Fe continued to fuel that growth with ever-increasing capacity, branch lines, and land grant sales. Thanks in no small measure to the railroad’s advance, the territory that President James K. Polk had wrested from Mexico sixty-some years before had become an integral part of the burgeoning United States. In 1846 the wagon master’s cry had been “On to Santa Fe!” Cyrus K. Holliday and his associates pushed their railroad to Santa Fe and then beyond. In doing so, they inexorably changed the landscape the rails traversed.

In 1870 the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe was not yet one-third of the way across Kansas. But between then and 1910, the population of the states and territories its main lines served—Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Oklahoma, and Texas—increased 5.7 times, more than twice the national average.

Those seven states and territories, encompassing one-third of the continental area of the United States, grew from populations of 1.9 million in 1870 to 10.9 million in 1910. This surge was perhaps most visible in the U.S. House of Representatives, where new apportionments and statehoods increased the region’s representation from nine congressmen in 1870 to fifty-one in 1910—a westward trend of population and political power that has continued into the twenty-first century.

Colorado became a state in 1876. Oklahoma, spurred by a land rush and oil discoveries, followed in 1907. By 1912, the territories of Arizona and New Mexico would round out the lower forty-eight states. And along the way, the towns served by the Santa Fe became the commercial hubs and political centers of a region where before there had largely been wild prairies, sweeping deserts, and quiet countryside.

With Santa Fe connections, Los Angeles and San Diego in California, Phoenix in Arizona, and Albuquerque and Las Cruces in New Mexico grew to prominence. The Santa Fe paced the Denver and Rio Grande along Colorado’s Front Range and boosted Denver, Colorado Springs, and Pueblo.

Along with the venerable Katy, the Santa Fe stocked the Oklahoma boom and brought competition to Dallas, Fort Worth, and Houston. More than anything else, it was the passenger prestige and freight tonnage of the Santa Fe that solidified Kansas City as the western gateway to the Southwest. Perhaps most important, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe tied together East and West along the most direct transcontinental route between the Midwest and the Pacific Coast.

Some would later say that Ripley had worked a “virtual miracle”—not just on the Main Streets of so many towns in the Southwest but on Wall Street as well. Ripley’s fiscal conservatism and calculated expansion had made the Santa Fe a “blue chip” investment. Meanwhile, his investment in the physical plant continued, including the double-tracking of the main line from Chicago to Newton, Kansas, by 1911.10

The road was “winning its right,” one contemporary financial writer noted, to be called “the Pennsylvania of the West.” In case there was any doubt exactly what that meant, the writer spelled it out: “The Pennsylvania policy is not one of parsimonious dividends, nor of shrinking from heavy capital expenses. It is one of liberal maintenance, aggressive expansion, and the free issue of stocks and bonds.” No doubt, J. Edgar Thomson smiled in his grave at that.11

When Edward Payson Ripley relinquished the presidency of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe on January 1, 1920, “the road had become universally recognized as one of the best physically and soundest financially, in the world, besides having established an enviable reputation for the character of service rendered.” It had indeed reached the top of the heap.12