Introduction

This chapter aims to provide evidence well-grounded in empirical research to address the questions of who in current China plans to study overseas and why they would like to study overseas. The goal is to better understand the driving force behind the largest outflow of international students from China. It is the first study employing large-scale data to thoroughly examine factors affecting Chinese students’ motives and decision-making in studying overseas and how those factors are related to students’ family socioeconomic status (SES). The data were collected from 18 high schools in the three cities of Beijing, Chengdu, and Shenzhen, between the summer of 2015 and the summer of 2016.

International Student Mobility and Institutional Motives

The direction in which international students flow is uneven, mostly from developing, non-English-speaking countries in the East such as China and India to developed, English-speaking countries in the West such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia (Perkins & Neumayer, 2014). In 2014, among the 4.5 million international students worldwide, about 53% are from Asia, and in Asia the top three sending countries of international students are China, India, and Korea (OECD, 2015). As Altbach and Knight (2007) pointed out: “International academic mobility … favors well-developed education systems and institutions, thereby compounding existing inequalities” (p. 291). However, starting around the mid-1990s the dominating position of English-speaking countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia as traditional popular destination for international students have been challenged, and new directions for student mobility have emerged: by the early 2010s some Asian countries such as China, Singapore, and Malaysia had become competitive destinations for foreign students (Knight, 2011; Tan, 2013).

It is widely recognized that receiving and educating international students has multiple benefits, including adding diversity to the student body, providing students in host countries with the first close contact they have with a person from another culture, filling the under-enrolled courses that colleges would otherwise find it difficult to offer and providing crucial support as teaching and research assistants, especially in the sciences (Bartlett & Fischer, 2011; Johnson, 2003; Rogers, 1984). However, there is no denying that financial consideration is an important factor in recruiting international students. In the majority of countries where data are available, international students pay higher tuition fees at public educational institutions than do national students enrolled in the same program. For example, in the United States, at public institutions international students are usually charged out-of-state tuition fees which are considerably higher than in-state tuition fees. In Austria, students enrolled at public institutions who are not citizens of the European Union or European Economic Area countries are usually charged twice as much in tuition fees as citizens of those countries. Similar policies of differential charges based on an individual’s citizenship or residence can be found in countries such as the United Kingdom, Canada, and New Zealand (OECD, 2014). In fact, Throsby (1986), who analyzed the Australian fee-charging policies toward foreign students in tertiary education from an economic perspective about three decades ago, supported the proposals to introduce a full economic fee for foreign students. Kinnell (1989) indicated that higher education institution in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia adopted a marketing approach in recruiting international students because of the pressure to generate revenues.

Financial incentives for recruiting international students have become more important in recent years. As educational institutions face an increasingly restrained budget situation after the 2008 financial crisis, many of them turn to the tremendous international student market for a solution. International education is a huge business indeed. For example, it is reported that higher education has become an important export product for the United States and ranks No. 5 in the service industry (Li & Zhang, 2011). In Australia, the total national exports of higher education, vocational education, schooling, and English-language courses were AUD ten million in 2009, and education had become the nation’s largest services export and fourth largest export after coal, iron ore, and gold, ahead of tourism, agriculture, and manufacturing (Marginson, 2011). The annual report Open Doors estimated that in 2015–16, international students had contributed $32.8 billion and 400,000 jobs to the US economy (IIE, 2016).

Given the multiple benefits of having international students, it is no surprise that nations compete against each other to attract international students (Knight, 2011). Therefore, it has become a priority for institutions and policy-makers to understand students’ motives and decision-making in studying abroad.

Push-and-Pull Factors

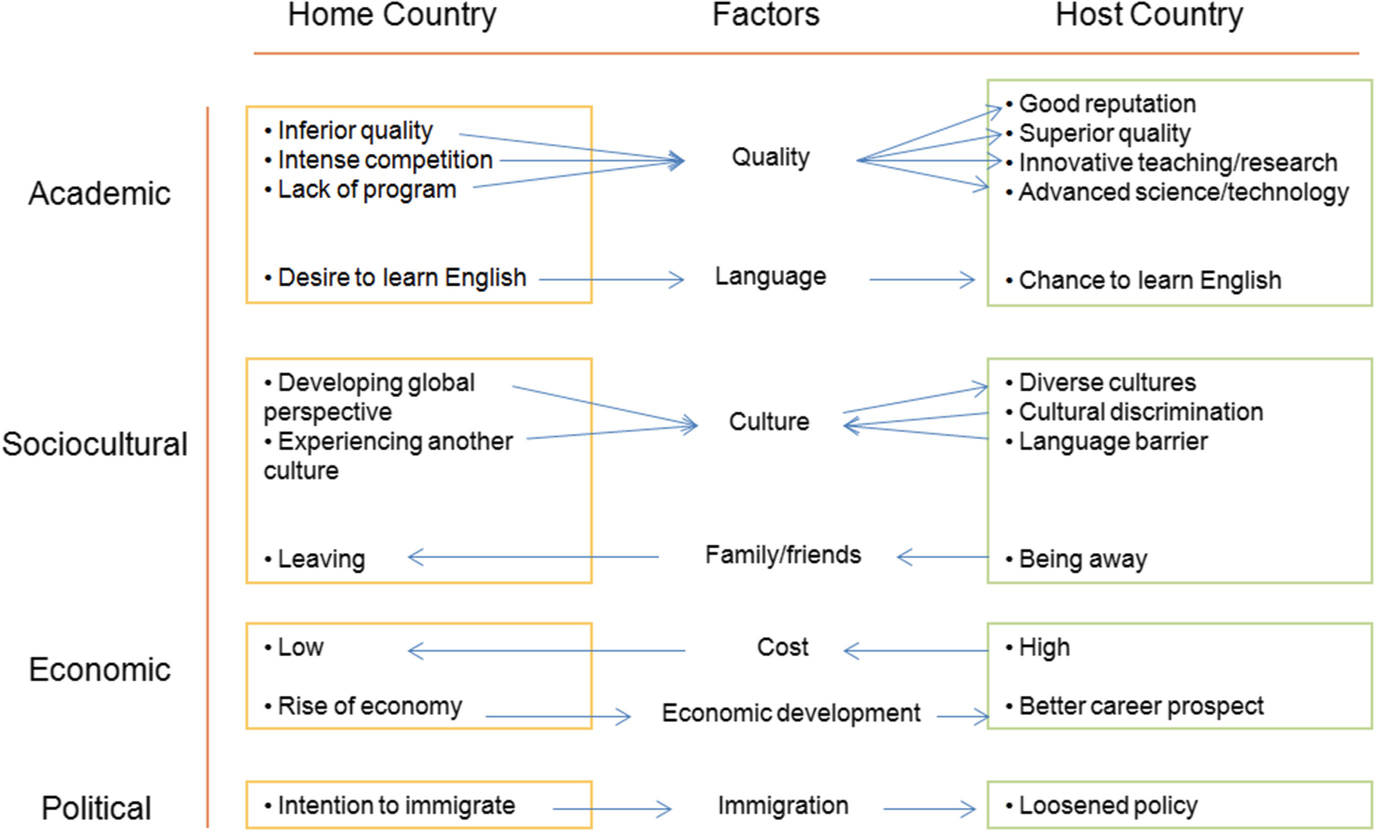

Studies have long existed examining factors related to international student mobility. Having guided researchers in migration for many years (Ravenstein, 1885; Stouffer, 1940), the push-and-pull framework is the most well-known and most widely used. It was Everett S. Lee who developed it into a model. He argues that both home and host countries have push (minus) and pull (plus) factors and that there are “intervening obstacles” (i.e., factors in between the home and host countries) such as distance, immigration laws, and transportation costs as well as personal factors such as personal sensitivities, intelligence, and awareness of conditions (Lee, 1966, p. 51). Donald Bogue (1969), one of the leading demographers in the United States enriched the model by identifying specific push-and-pull factors. The push factors in his list include decline in a national resource, loss of employment, oppressive or repressive discriminatory treatment, alienation, and retreat from a community because of ideological reasons, lack of opportunities, or catastrophe. The pull factors include superior opportunities for employment, opportunities to earn a larger income or to obtain desired education or training, preferable environment and living conditions, the movement of dependents, or lure of new or different activities, environments, or people.

Among the early works that used the push-and-pull framework in education, Agarwal and Winkler (1985) identify the following factors as the principal flow drivers: per capita income in the home country, the price or cost of education, the education opportunities available in the home country, and expected benefits of studying abroad. Altbach (1991) identifies as an important push factor the unfavorable conditions in home countries, and pull factors include advanced research facilities, congenial socioeconomic and political environments, and the prospect of multinational classmates. McMahon (1992), after examining the flow of international students from developing to developed countries in the 1960s and 1970s, identifies the following push factors: the level of economic wealth, the degree of involvement of the developing country in the world economy, the priority placed on education by the government of the developing country, and the availability of educational opportunities in the home country. The following pull factors are identified in his study: the relative sizes of the student’s home country economy compared to the host country, economic links between the home and host country, host nation political interests in the home country through foreign assistance or cultural links, and host nation support of international students via scholarships or other assistance.

Mazzarol, Kemp, and Savery (1997) identify the following six pull factors: (1) overall level of knowledge and awareness of the host country in the students’ home country; (2) level of referrals or personal recommendations that the study destination receives from parents, relatives, friends, and other “gatekeepers” prior to making the final decision; (3) cost issues, including the financial cost of fees, living expenses, travel costs and social costs, such as crime, safety, and racial discrimination; (4) environment, which refers to the study “climate” in the destination country, as well as its physical climate and lifestyle; (5) geographic proximity, which is related to the geographic (and time) proximity of the potential destination country to the students’ country; and (6) social links, which is related to whether a student has family or friends living in the destination country and whether family and friends have studied there previously. Mazzarol and Soutar (2002) list “the desire to have a better understanding of the Western culture” as another pull factor. Azmat et al. (2013) expand the Mazzarol and Soutar (2002) study by identifying additional push factors such as economic wealth, educational opportunity, educational standards, and family influence, and additional pull factors such as university reputation, quality and choice of programs, staff quality and permanent residency. A more recent study by Foster (2014) identify four groups of factors, namely, cost, past social relationships, language, and homesickness.

Worth of mentioning is the improved push-and-pull framework proposed by Li and Bray (2007) which is the main framework used in the analysis of this chapter. Li and Bray (2007) call the pull factors in home countries and push factors in host countries “reverse push-pull factors” (p. 795), and they distinguish among four groups of factors: (1) push factors in home countries and (2) pull factors in host countries, both of which provide pushing force for motivating students to leave their home countries, as well as (3) pull factors in home countries, and (4) push factors in host countries, both of which are pulling force for students not to leave their countries. To further develop the push-and-pull factor framework, Li and Bray (2007) proposed to use four categories of motives: academic, economic, social and cultural, and political.

Even though studies have been done on factors affecting Chinese students’ decision-making in studying overseas, they are either about reasons why they choose certain countries, such as Australia and the United Kingdom (Azmat et al. 2013; Counsell, 2011; Iannelli & Huang, 2014), or about the mobility of Chinese students within Greater China, including Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan (Bodycott & Lai, 2012; Li & Bray, 2007; To, Lung, Lai, & Lai, 2014). Bodycott (2009) is among the few studies examining factors affecting Chinese students’ choice of study-abroad destinations using empirical data, and its mixed-method design helped to provide valuable information on Chinese students’ motives in studying overseas along with their parents’ attitudes. However, the focus of this study is how children and parents differ in their ratings of the factors. Further, the participants in this study were recruited at international education exhibitions or information sessions on studying overseas, which limited the generalizability of the findings as people attending those events were self-selected. Further, the sample size was only 100, which was quite small.

Methods

Research Questions

- 1.

What are the characteristics of Chinese high school students who plan to study overseas?

- 2.

What factors affect Chinese high school students’ decision-making in going abroad to study?

Data Collection

The data used in this study were collected at six public high schools in each of the three cities of Beijing, Shenzhen, and Chengdu, making it a total of 18 schools. Altogether 3275 surveys were distributed at those schools, and 3001 of them were completed and returned, which resulted in a high response rate of 91.6%, thanks to the assistance of the schools in distributing and collecting the survey. The survey included information on students’ demographics, socioeconomic status, plans regarding studying overseas, reasons for and concerns over studying overseas, perceived costs and benefits of studying overseas.

The three cities of Beijing, Shenzhen, and Chengdu were chosen to represent large cities in China since those cities are where the majority of Chinese students studying overseas come from. Beijing is located in the Northern part of China, and as the nation’s capital, it is a political and cultural center. Shenzhen is located in the Southern part and along the coastal line, and as the first and largest Special Economic Zone in South China, it is among the most economically advanced cities in China. Chengdu is located in the Southwest, and as the capital of Sichuan Province which is the largest province in China, it is the cultural and economic center in the Western region of China.

This study makes contributions to the existing body of literature on the motives and decision-making process of Chinese students in the following three aspects. First, the use of large-scale dataset from three cities located in different parts of China provide a better representation of the student population and thus enable the researchers to do a more comprehensive investigation on the motives and decision-making among Chinese high school students. Second, although there have been studies done on the factors related to international student mobility and also Chinese students’ flow out of China, they are mostly at the postsecondary level. This empirical study is among the first to examine Chinese students at the high school level. Unlike other studies which gather information from students who are already enrolled in a postsecondary institution overseas, this study investigates their motives and decision-making process while they are still in the preparation or decision-making stage. Third, this study is the first to examine how the factors are related to students’ family SES, and knowing more about this relationship may have important implications for preparations that need to be done on the students’ part, as well as improvement that could be made in the recruitment and service efforts on schools’ part.

Findings and Discussion

Characteristics of Participants: Those Who Plan to Study Overseas Vs. Those Who Do Not

Individual Characteristics

Summary statistics, overall, and by plan for studying overseas

Demographic | Overall | Students planning to study overseas | Students not planning to study overseas | Undecided students |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Female* | 55.9 (N = 2978) | 58.6 (N = 784) | 50.2 (N = 380) | 56.8 (N = 459) |

Agea | 17.4 (0.02) N = 2854 | 17.3 (0.03) N = 1284 | 17.5 (0.04) N = 729 | 17.3 (0.04) N = 774 |

Academic performance (at school) | ||||

Overall** | N = 2620 | N = 1122 | N = 703 | N = 740 |

Top 10% | 17.1 | 23.5 | 12.9 | 11.8 |

11–30% | 30.2 | 29.4 | 30.4 | 30.9 |

31–50% | 26.3 | 26.3 | 24.6 | 28.1 |

Below 50% | 26.5 | 20.8 | 32.0 | 29.2 |

Math** | N = 2512 | N = 1079 | N = 677 | N = 708 |

Top 10% | 17.5 | 23.8 | 15.2 | 10.3 |

11–30% | 29.9 | 30.3 | 27.2 | 31.6 |

31–50% | 26.9 | 25.0 | 27.6 | 29.2 |

Below 50% | 25.6 | 20.9 | 30.0 | 28.8 |

English** | N = 2516 | N = 1077 | N = 676 | N = 713 |

Top 10% | 19.0 | 27.2 | 12.0 | 13.6 |

11–30% | 27.2 | 29.1 | 25.1 | 25.9 |

31–50% | 25.3 | 22.4 | 24.3 | 30.9 |

Below 50% | 28.5 | 21.4 | 38.6 | 29.6 |

Chinese** | N = 2503 | N = 1069 | N = 676 | N = 710 |

Top 10% | 18.0 | 25.4 | 13.0 | 11.5 |

11–30% | 30.2 | 28.8 | 31.8 | 31.0 |

31–50% | 27.6 | 24.8 | 29.0 | 31.0 |

Below 50% | 24.1 | 21.0 | 26.2 | 26.5 |

Father’s education** | N = 2822 | N = 1270 | N = 728 | N = 764 |

Associate or below | 50.4 | 33.9 | 64.7 | 64.3 |

Bachelor’s degree | 33.5 | 40.9 | 26.2 | 28.4 |

Graduate degree | 16.1 | 25.2 | 9.1 | 7.3 |

Mother’s education** | N = 2812 | N = 1266 | N = 723 | N = 763 |

Associate or below | 57.8 | 42.3 | 71.4 | 70.9 |

Bachelor’s degree | 31.3 | 41.1 | 22.0 | 24.0 |

Graduate degree | 10.9 | 16.6 | 6.6 | 5.1 |

Father’s occupation** | N = 2777 | N = 1246 | N = 719 | N = 760 |

Government official | 8.3 | 10.8 | 6.7 | 5.9 |

Business | 40.9 | 46.1 | 33.7 | 40.0 |

Professional | 18.1 | 18.9 | 18.6 | 16.3 |

Worker, farmer, and other | 32.7 | 24.2 | 41.0 | 37.8 |

Family annual income (2014)** | N = 1172 | N = 481 | N = 369 | N = 298 |

<100,000 yuan | 30.4 | 15.8 | 42.0 | 39.3 |

100,000–190,000 yuan | 28.7 | 22.7 | 33.1 | 33.6 |

200,000–290,000 yuan | 13.0 | 16.2 | 10.6 | 11.1 |

300,000–490,000 yuan | 9.7 | 15.2 | 4.6 | 7.4 |

500,000–1 million yuan | 9.4 | 15.0 | 5.1 | 6.0 |

>1 million yuan | 8.8 | 15.2 | 4.6 | 2.7 |

Generally speaking, students planning to study overseas have better academic performance than those not planning to study overseas and those who are undecided. For example, 23.5% of the students planning to study overseas rank themselves among the top 10% (N = 1122) in their overall academic performance, as compared to 12.9% for students not planning to study overseas (N = 703), and 11.8% for undecided students (N = 740). The differences among those three groups of students in their overall academic performance is statistically significant (p < 0.001). Among the three main subjects of math, English and Chinese, the differences among the three groups seem to be the largest for English (p < 0.001).

Family Characteristics

Accompanying the rapid economic development and the establishment of market as the dominating force for allocating resources, China has been undergoing social transformation which is characterized by rapid social stratification during the past several decades. According to Lu Xueyi, a renowned sociologist in China, the largest change in social strata in recent years lies in the increase in the number of white-collar workers and professionals, civil servants, and private business owners, which all belong to the rising “middle class” (Lu, 2010). In particular, two social groups have caught attention in recent years among the public, the media, as well as scholars and researchers, and they are labeled “fuerdai” and “guanerdai,” which refer to the offspring of government officials and wealthy business people, respectively. Showered with inherited privilege of power and wealth, those children carry important labels of new social strata (Zhang, 2013).

The following analysis on family characteristics and on the relationship between family SES and motivating factors pays particular attention to those groups which are at an advantage in building networks and mobilizing social resources, namely, civil servants (referred to as “Official” hereafter), business owners (“Business” hereafter), and white-collar professionals (“Professional” hereafter). Children of those three groups are examined in reference to others (“Other” hereafter) in order to have a more nuanced understanding of how family SES is related to students’ motives in studying overseas as those three subgroups of students are likely to enjoy more social resources because of their advantaged social status.

Overall, the parental educational level of the participants seems to be pretty high compared to the general population: 33.5% of the students have a father with a bachelor’s degree and 16.1% a graduate degree (N = 2822); 31.3% of the mother with a bachelor’s degree and 30.9 a graduate degree (N = 2812). Since there is a well-established high correlation between parental education and parental occupation, it is no surprise that the occupation of the participating students seem to be of relatively high social status: 8.3% of the fathers are government officials, 40.9% are business people, 18.1% are professionals, and only 32.7% belong to other relatively disadvantaged social strata (N = 2777). Family annual income also seems to indicate that the participating students tend to come from relatively privileged family backgrounds: Among the participants who provided valid information, only 30.4% of the family had an annual family income below 100,000 yuan1 in 2014, 69.6% of the family had an annual income above 100,000 yuan, including 8.8% above one million yuan. The relatively privileged family backgrounds of the participants reflect the relatively high family socioeconomic status of residents in large cities, which has the highest concentration of high-income population with high educational level and high professional status. By comparison, students planning to study overseas have more privileged family backgrounds than those who do not plan to study overseas and those who are undecided, as reflected in higher parental educational level, parental occupation with higher social status, and high family income.

To sum up, students who plan to study overseas distinguish themselves from the other students by relatively high academic performance and high family socioeconomic status indicated by parental education, parental profession, and family income. In other words, it seems that, in order for students to have the determination to study overseas, they need to have confidence in both their own academic capability and their family’s financial capability to support them. Interestingly, there is no evidence suggesting any differentials among the three cities in the characteristics of students who plan to study overseas and their family backgrounds.

Factors Affecting Students’ Decision-Making

Factors related to students’ decision-making in studying overseas

Factors | No. 1 | No. 2 | No. 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

Education-related reasons for studying overseas (N = 1384) | Inferior overall quality of domestic institutions (48.5a) | Intense competition (15.0) | Lack of programs of my interest (12.8) |

Reasons for choosing an institution (N = 1354) | High-quality teaching staff (29.7) | Good reputation (29.0) | Innovation in teaching and research (17.7) |

Reasons for choosing a country (N = 1277) | High-quality education (46.4) | Advanced science and technology (14.0) | Diverse culture (11.4) |

Destination country of choice (N = 1275) | The United States (61.6) | The United Kingdom (11.5) | Canada (7.6) |

Non-educational reasons for studying overseas (N = 1340) | Gaining global perspectives (32.7) | Better career prospect (17.5) | Experiencing another culture (14.8) |

Concerns over studying overseas (N = 2635) | High cost (37.0) | Language barrier (19.1) | Away from family and friends (10.4) |

Benefits of studying overseas (N = 1156) | Learning advanced technology (34.2) | Gaining global perspective (17.8) | Obtaining a foreign diploma which carries more weight (13.0) |

Summary of push-and-pull factors

Academic Factors

As shown in Table 4.2, among the 1384 students who plan to go overseas to study, the top three education-related reasons for studying overseas are (1) the inferior overall quality of domestic institutions, (2) intense competition, and (3) lack of the programs of my interest. Academically, educational quality and educational opportunity seem to be the biggest factors. This finding confirms existing studies which proved dissatisfaction of Chinese students and their families with the increasingly crowded environment of the higher education system in China, as well as with the quality of curricula and teaching methods “which are considered to be not as advanced and up-to-date as those adopted by higher education institutions in Western countries” (Iannelli & Huang, 2014, p. 808).

In spite of the rapid expansion of Chinese higher education during the past few decades, it is still quite competitive to enter a decent college or university. In 2015, the total enrollment at higher education institutions was nearly 36.47 million (Ministry of Education, 2016), and the enrollment rate among students between the ages of 18 and 22 reached 40.0%, compared to 15% in 2002 and 3.4% in 1990 (Wu & Lu, 2002). Nonetheless, the National College-Entrance Examination is still the main avenue through which students can access higher education. As a result, the competition for entering a quality higher education institution is still quite intense.

Corresponding to the above-mentioned factors in China which are pushing Chinese students overseas are better university reputation as well as high quality and more choice of programs in host countries which serve as pulling forces. In evaluating an institution’s quality, 29.7% of the participants rank “high-quality teaching staff” as the No. 1 factor, 29.0% rank “good reputation” as the No. 2 factor, and 17.7% rank “innovation in teaching and research” as the No. 3 factor (N = 1354). The importance of academic reasons for studying overseas is highlighted by the fact that “learning advanced technology” is ranked as the No. 1 perceived benefit of studying overseas. Those academic pulling forces in host countries are confirmed by existing literature (Azmat et al., 2013; Iannelli & Huang, 2014; To et al., 2014).

In other words, the major motive behind the Chinese student mobility seems to be learning, which is rather reassuring, especially considering recent media coverage on international students from China who do nothing but showing off their wealth. As a recent report in the Chronicle of Higher Education says: “Here’s what Americans think about the Chinese students who have been crowding their campuses: They all drive fancy cars, and they all are rich” (Fischer, 2015).2 The Chinese students who go overseas in recent years are very different from their predecessors who had embarked on the same journey two decades earlier. A recent article in Foreign Policy (Liu, 2015) depicts some typical Chinese students studying overseas in the 1980s and 1990s: They tended to be among “the nation’s best and brightest”; they are usually “… penniless … didn’t go out to dinner, didn’t go to parties, and assumed that American students were all really rich”; and they tended to be “idealistic and patriotic.” In less than two decades, the image of the humble and diligent Chinese students studying overseas has transformed drastically and is replaced by the image of the “nouveau riche,” or “the second-generation scion in a wealthy family, who studies abroad in order to return home to run the family business.” They “pay full tuition, often study finance, business management, or economics, and spend their time clustered together”; and they drive luxury cars and go into the city “for extravagant weekend shopping trips.” As Liu pithily summarized: “It’s not just a thickening wallet that separates yesterday’s overseas Chinese student from today’s. Many have noted a shift in the academic goals and underlying motivations pulling Chinese scholars” to study overseas.

In spite of the negative media coverage, it seems that learning is still the main driving force behind the large outflow of Chinese students, and the importance of learning is confirmed by the reasons for students’ top three choices of No. 1 destination country, which are the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. 46.4% of the participants choose “high-quality education” as the No. 1 reason (N = 1277).

Sociocultural Factors

As Beine, Noel, and Ragot (2013) indicated, cross-border migration of international students may also be viewed as a consumption choice. In that case, students not only consider the returns to their educational investment, they also consider the circumstances and the place where they will study. The facts that “gaining global perspectives” is ranked as the No. 1 non-educational reason for studying overseas, and that “diverse culture” is ranked the No. 3 reason for choosing a particular country, all demonstrate that social and cultural experiences are important considerations for Chinese students in their decision-making regarding studying overseas. In fact, 22.1% of the participants (N = 1101) indicate that they do not care whether they will be able to recover the cost of studying overseas.

A few in-depth stories in a recent report in the Chronicle of Higher Education depicting Chinese families who send their children overseas reflect the importance of sociocultural factors in the decision-making process (Fischer, 2015). Abby Wu has a mother who is an executive in a prosperous Chinese company and father who works in satellite communication. In spite of their high-paying jobs, Abby’s parents describe themselves as a “normal family,” which means that they lack the “connections” which can help one “secure a position, particularly in government or state-owned companies.” Her parents had contemplated on the option of studying abroad which they thought would guarantee her a “more certain future” since she was in middle school. Beini Wang’s parents are both instructors in a local university, and they had dreamed about sending their daughter overseas to study because they wanted her to “learn something” and they thought the test-centric educational system in China was “exhausting and boring.” Being professionals whose combined yearly salaries of 200,000 yuan (an equivalent of $32,000), paying for an American undergraduate education is out of the question. But they sold their large, well-located apartment and bought a smaller, less expensive one, which helped them to pay for the cost. It is not uncommon for families to pay for an education abroad using the profit made from the skyrocketing real-estate prices. Like most Chinese parents, Beini’s parents think it is well worth it. “It’s not an investment,” her mother says, “It’s our child’s life.” As the report summarizes: “For Chinese parents, the choice of an American education for their child—and almost always their only child—is not just a financial investment. It’s a political maneuver, a personal sacrifice, a bet on greater opportunity abroad.”

As counter force to the above-mentioned external sociocultural pull factors, external sociocultural push factors such as cultural and language barriers, as well as having to be away from family and friends, serve to deter students. As a culture that attaches great importance to family and values friendship, it is conceivable that Chinese students may not want to go overseas to study because they do not want to be away from their family and friends.

Economic Factors

From a human capital perspective, going to another country to study is considered an investment and the motive is to have better job opportunities and thus higher expected income in the future. In fact, 17.5% of the participants rated “better career prospects” as the No. 2 non-educational reason for studying overseas. Therefore, those economic considerations serve as important pulling forces in destination countries. And along with them, the rise of China’s economy serves as an important pushing force within China. Studying overseas used to be the privilege reserved for the few most wealthy and powerful elite in China, but now even an average white-collar professional can afford to send their children abroad thanks to the rapid economic development in China, which is reflected in higher living standards, more wealth accumulated among individuals, skyrocketing real-estate price, as well as the appreciation of the Chinese currency.

In spite of the increasing affordability of studying overseas, its financial cost is still a major consideration for most Chinese families, and thus serves as a push factor in host countries. As shown in Table 4.2, 37.0% of the participants identify “high cost” as the No. 1 concern, and 17.5% of those who plan to study overseas rank “better career aspect” (which is associated with higher income) as the No. 2 non-educational reason. Further, 52.8% of the participants think that they would consider studying overseas only if the cost accounts for less than 30% of their annual family income, 21.9% can accept between 30 and 50%, and only 10.5% can accept above 50% (N = 2634). In addition, 56.5% of the participants expect to recover the cost of studying overseas within 5 years after graduation, 16.6% between 5 and 10 years and 2.1% between 10 and15 years (N = 1101).

Political Factors

Loosened restrictions on visa and immigration in host countries have been identified as a pulling force (Bodycott, 2009; Lee, 1966; To et al., 2014). Interestingly, this does not prove to be an important factor among Chinese students. For example, only 6.7% of the participants (N = 1340) who plan to study overseas identify immigration as the No. 1 non-educational reason for studying overseas, and only 2.3% (N = 1277) of them choose loosened immigration policy as the No. 1 reason for choosing a particular country.

Conclusions

As the world becomes increasingly interconnected and interdependent economically, politically, culturally, and socially, international student mobility can only become more frequent and thus remains an important topic. Using the push-and-pull framework based on data collected from 3001 students at 18 high schools located in the three cities of Beijing, Shenzhen, and Chengdu, this study identifies important factors in the academic, economic, sociocultural, and political aspects that serve as the pushing and pulling forces in students’ decision-making process of studying overseas. The finding that sociocultural factors such as “experiencing another culture” and “gaining global perspective” play a significant role is an interesting one. Further, the findings reveal the importance of students’ academic preparation and their families’ financial capability.

Currently, the majority of Chinese students studying overseas come from large cities, and the choice of the three cities of Beijing, Shenzhen, and Chengdu in this study was made to reflect this trend. However, sporadic data has shown that this trend has been trickling down to smaller cities. Worth mentioning is that studies conducted by the authors in a small city on the east coast of China have shown similar trends in terms of students’ motives in and families’ decision-making about studying overseas.