IN OCTOBER 1683, Josiah Franklin, his wife Anne, and their three small children gazed hungrily for their first sight of land. They’d left England nine long weeks before on a cramped ship packed tight with 100 other passengers and crew. Twenty-five-year-old Josiah hoped not only to find religious freedom in New England but also to better support his growing family. In Massachusetts a man could live more cheaply and earn more for his hard work. In Boston the Franklins would build a new life.

Josiah labored as a silk and fabric dyer in England. But the Puritans of Boston fined people for wearing fancy clothes or for dressing above their place in society. To make a go of things in the New World, Josiah tackled a new trade—he became a tallow chandler, a maker of candles and soap.

On the corner of Milk Street and High Street, Josiah and Anne rented a two-and-a-half-story clapboard house that also served as Josiah’s shop. The ground floor had one long room. To protect the main house from fire, the kitchen was out back in a separate building. Across the street stood South Church, the newest of Boston’s three church congregations.

More children filled the Franklin house, but like many homes in colonial America, death stalked the family, too. A baby son died. Then Anne Franklin died, leaving behind a week-old son, who soon followed his mother to the grave. Left with five children to care for, a trade to work, and a shop and home to run, Josiah needed a new wife and helpmate. People remarried quickly in colonial America. Five months after Anne’s death, Josiah married Abiah Folger. Her father, Peter Folger, had been an early settler of New England.

Benjamin Franklin’s birthplace on Milk Street in Boston.

Over the next 12 years, Abiah and Josiah’s family grew, though tragedy always waited on the doorstep. Two more little sons died, including 16-month-old Ebenezer, who drowned in the tallow shop’s boiling vat. On January 17, 1706, Abiah gave birth to a new baby boy. They named him Benjamin after Josiah’s brother.

Josiah bundled the new baby into blankets and carried him across the street to South Church. Puritan parents viewed life as a mighty struggle between God and the devil, and since death might snatch their infants at any moment, it was best to quickly baptize a newborn. If death came, the child’s cleansed soul was ready for heaven.

But Ben did not die—he thrived, healthy and strong, in a home filled with brothers and sisters. Two more baby girls joined the Franklin mob. The last one, named Jane, became young Ben’s favorite of all his siblings.

ROUGHLY 7,000 people called the thriving town of Boston home. As the third-largest shipping center in the whole British Empire, Boston’s waterfront rocked with ships and swarming seamen loading and unloading cargo along the wharves. Josiah prospered enough to move his family from the tiny house, once crammed elbow-to-elbow with 14 children, to a larger home and shop in the center of town. By the time Ben was six, many of his elder siblings had left to make their own way in the world.

ROUGHLY 7,000 people called the thriving town of Boston home. As the third-largest shipping center in the whole British Empire, Boston’s waterfront rocked with ships and swarming seamen loading and unloading cargo along the wharves. Josiah prospered enough to move his family from the tiny house, once crammed elbow-to-elbow with 14 children, to a larger home and shop in the center of town. By the time Ben was six, many of his elder siblings had left to make their own way in the world.

Rivers, bays, and inlets led to the sea, and young Ben Franklin played often “in and about” the water. He learned to swim and handle a boat. He fashioned flippers for his hands and feet to see if they helped him swim faster. And once, he used a kite to pull himself back and forth across a pond.

JOSIAH FRANKLIN belonged to the Puritan church. In the 1500s some members of the official Church of England felt their church followed too many Catholic rituals. Their church needed “purifying.”

Puritans believed every person could (and should) read, study, and discuss the Bible. They believed in sermons to enlighten the soul. They believed each church congregation should be self-governing, not run by bishops or a pope. They held strict views on moral conduct. Puritans believed men showed respect for God by working hard. A man’s success showed that God smiled upon him. Boston, founded in 1630 as the Puritan’s shining “City on a Hill,” became the center for Puritan America.

Puritans loved words like diligence, obedience, duty, and industry—meaning hard work. Idleness and time wasting opened the door to temptations from the “great deluder,” Satan. In 1715, Isaac Watts wrote a poem to turn children from idleness and mischief.

How doth the little busy Bee

Improve each shining Hour,

And gather Honey all the day

From every opening Flower!…

In Works of Labour or of Skill

I would be busy too:

For Satan finds some Mischief still

For idle Hands to do.

Rock candy is made from growing sugar crystals. This candy has been around for centuries. It was also used as a medicine to soothe sore throats.

MATERIALS

Adult supervision required

First, use a hammer to punch two nail holes in the canning jar lid about 1½ inches apart.

STEP 1: Make Rock Candy Syrup

In a quart pan, bring ¾ cup of water to a boil over medium heat. Stir the sugar into the boiling water. Keep stirring for about two minutes until the liquid turns clear. Cook for one more minute to make sure all the sugar crystals have dissolved, but do not overcook!

Carefully pour the hot syrup into the canning jar. Add a few drops of food coloring if you’d like. Let the syrup cool to room temperature. This may take a while.

STEP 2: Seed the Skewers

While the rock candy syrup cools, you can “seed” the skewers. You must seed the wooden skewer so that the sugar crystals have something to attach to. Have an adult cut a 10-inch skewer in half with a utility knife. Each piece should be about 5 inches long.

To a frying pan, add 2 tablespoons of sugar and 1 teaspoon of water. Cook over medium heat, stirring constantly. The mixture will eventually turn into a thick liquid syrup. But do not let the syrup get too hot or it will turn dark.

Turn off the heat. Use a butter knife to quickly spread the skewers, one at a time, with the syrup. Before the syrup hardens, hold each skewer over a plate and sprinkle it with sugar.

Soak the frying pan before cleaning.

STEP 3: Make Rock Candy

Stick the two unsugared ends of the seeded skewers through the holes in the jar lid. If they do not stay in without sliding, lightly tape them in place from the top.

Lower the sticks into the cooled syrup. Adjust the sticks so they do not touch.

Place the jar in a warm spot, between 70 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit, for one week. Near a TV is usually a good place. Every day watch the crystals as they grow on the skewers.

After one week lift the lid holding the skewer sticks and pour off the syrup. If necessary, break the rock candy away from the bottom of the jar.

Let the candy dry on a clean plate. Once dry, eat and enjoy—or use it to stir hot tea for a sweet drink.

Ben’s friends looked to him as their captain, even though sometimes he led them “into Scrapes.” Once, after they’d trampled their favorite fishing spot into a muddy mess, Ben proposed building a proper wharf to fish from. One night he and his pals lugged away a heap of stones meant for a new house. The boys constructed their stone wharf, but the next morning all was discovered—the missing stones, the newly built wharf, and the boys’ identities! “Several of us were corrected by our Fathers,” remembered Franklin, “and tho’ I pleaded the Usefulness of the Work, mine convinc’d me that nothing was useful which was not honest.” In colonial America, corrections usually meant a spanking or whipping.

Young Ben reads by candlelight.

ONE DAY Ben came upon a boy blowing a whistle. Oh, how Ben wanted that whistle! He offered the boy all the coins in his pocket and arrived home to show off his new treasure. But his brothers and sister scoffed that Ben had paid much more than the whistle was worth. Ben cried with frustration over wasting his money. The whistle now gave him little pleasure. Franklin learned from the whistle and the taunts of his siblings. One of the things he became most famous for was being careful and frugal with his money.

Marbles was a popular game for children in colonial America. Most marbles at the time were made of fired clay, not glass.

MATERIALS

On a bare floor, indoors, make a circle about 15 inches across using pieces of masking tape. Or, if you are playing outside, you can use chalk to draw a circle or scratch out a circle in the dirt using a stick.

Each player keeps a “shooter” marble. This is usually a larger marble. Put the rest of the marbles in the center of the circle.

Draw a line about a foot away from the circle. This is the taw line. Each player kneels behind the line and shoots his or her marble into the circle. To shoot, face your palm up, hold the marble in your curled forefinger, and flick it with your thumb. Or, you can set your marble on the ground and flick it with your forefinger.

The goal is to knock marbles out of the circle. If you knock a marble out of the circle, you get to shoot again. If you miss, the next player becomes the shooter. Collect the ones you knock out. The player who knocks out the most marbles is the winner.

But young Ben did not always stir up trouble. The lad also possessed a passion for books and learning. Franklin later recalled, “I do not remember when I could not read.” He read anything and everything he could lay his hands on. Josiah wondered if he had a scholar on his hands. Should he train Ben to serve as a minister, one of the most highly regarded and respected professions?

Josiah enrolled eight-year-old Ben in the Boston Latin School, the fast track for boys heading to the minister training ground of Harvard. Ben excelled, swiftly climbing to the head of the class. But Josiah pulled Ben from the school after less than a year, perhaps fearing the expense of a Harvard education. Or maybe he had a feeling Ben would not make a very good minister. The bright and curious boy sometimes offered opinions a bit strong for his family. One fall, as the Franklins salted and prepared their meat to store for the winter, Ben suggested they bless all the meat at once to save time saying grace before each meal. Perhaps not minister material!

Josiah instead sent Ben to a school that concentrated on reading, writing, and math, a subject Ben failed and “made no Progress in it.” After a year Ben Franklin’s formal school days ended, but he’d spent more time in school than most children in colonial America.

MOST COLONIAL boys’ education centered on an apprenticeship. Parents signed papers binding their child in service to a craftsman or tradesman. In exchange for the child’s work, the master taught him the skills needed for a future job. An apprentice belonged to his master and enjoyed few freedoms. The apprentice could not leave the master’s home or business without permission. Older apprentices were forbidden to marry, gamble, or go out to taverns.

MOST COLONIAL boys’ education centered on an apprenticeship. Parents signed papers binding their child in service to a craftsman or tradesman. In exchange for the child’s work, the master taught him the skills needed for a future job. An apprentice belonged to his master and enjoyed few freedoms. The apprentice could not leave the master’s home or business without permission. Older apprentices were forbidden to marry, gamble, or go out to taverns.

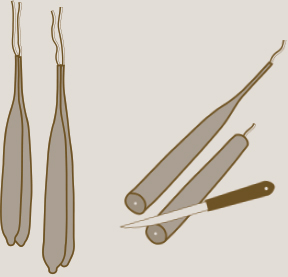

At age ten, Ben joined his father in the tallow shop. Tallow, the fat from cattle, was simmered for hours with lye, made from wood ash, to make soap and candles. Ben recalled his jobs “cutting Wick for the Candles, filling the Dipping Mold, & the Molds for cast Candles, attending the Shop, going of Errands” and soon hated the smelly, hot, tedious work.

Josiah feared unhappy Ben might run away and become a sailor, and he’d already had one son perish at sea. He explored other options with his son. He walked Ben about Boston, observing the many craftsmen and tradesmen at work—silversmiths, tanners, coopers (barrel makers), bricklayers, joiners (furniture makers), blacksmiths, and more. In the end Josiah apprenticed Ben in 1718 to one of his elder sons, Ben’s half-brother James, who was a printer. James had Ben, now twelve years old, sign an unusually long apprenticeship of nine years.

In Josiah Franklin’s chandler shop, soap was made from boiling together a smelly mixture of lye and animal fat, not something we’d really like to use to clean ourselves today.

MATERIALS

Adult supervision required

Using a butter knife, cut off two to four squares of glycerin, depending on the size of the soap mold. Two or three squares make about one small bar of soap.

Put the squares into a glass measuring cup. Put the cup in a microwave oven and melt on high for 40 seconds. If the glycerin is not all melted, add 10 more seconds.

If you wish, add a few drops of coloring into the melted glycerin and stir with the spoon. If you want a deeper color, add more drops. If you are using fragrance, add a drop to the melted soap.

Pour the glycerin from the measuring cup into the soap mold. Let the soap cool and firm up, about 30 minutes. When it has reached room temperature, tip the mold over and use gentle pressure to pop out the bar of soap. If it sticks, run hot water over the bottom of the mold and try again.

If your soap mold has places for several bars of soap, try melting and pouring one bar at a time to make each soap a different color. Just rinse out the measuring cup before melting the next batch. Let them all cool at the same time.

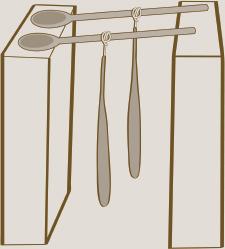

Ben worked in his father’s soap-making and candle-making shop and hated the hot, smelly work. Colonial candles were usually made of animal fat boiled with lye, poured into molds or from wicks dipped into the melted tallow.

MATERIALS

Adult supervision required

With an adult helping, cut or shave hunks of wax and put them into your melting pot or old can. Set the melting pot inside another larger pot. Add water to the bottom pot. Over medium heat, start melting the wax. This could take a while, but keep an eye on it.

When the wax is melted, add coloring and scent, if desired. Turn off the stove.

You can make two candles. Cut your wicks 12 to 14 inches long. Tie one end of the wick to a wooden spoon handle. Quickly dip the wicks, one at a time, into the melted wax. Lift the wick. Do not let the wick stay in the hot wax too long when you are dipping or you’ll melt the wax you’ve already put on the wick.

For the first few dips, gently pull both ends of the wick to keep the wax forming on a straight line, so the finished candle will not be crooked. Keep dipping the wick into the wax. Each time the wax builds up a bit more. It takes many dips to make a candle. Let the wax set up and cool for a few minutes between dips. You can rest the wooded spoon between two canisters, cereal boxes, or the like to cool.

When your candles are the desired thickness, cut each bottom off straight with a knife. Cut each wick to a half inch long. Now you can use your candles.

The two brothers probably did not know each other very well. Older by nine years, James had studied printing in England before returning to Boston and setting up his own shop. Ben, along with James and his other apprentices, boarded with another family. Already keen on living a frugal life, Ben made a deal with James: he’d feed himself if James would hand over half the money he paid for Ben’s food. James agreed. Ben squirreled away some of the money by eating a meager diet of water, bread, raisins, and sometimes a biscuit or tart.

As much as Ben disliked working for James, who sometimes beat him, printing suited young Ben much better than the candle and soap business. He loved being around the printed pages full of information, loved hearing the news customers bantered about the shop. The place smelled of ink and leather and wood and paper. Crowded cases holding compartments of tiny metal letters lined the walls. The capital letters were stored in the upper cases.

Ben pours tallow into candle molds.

Ben prepares to ink the type by rolling the ink between two padded leather “balls.”

The shop printed the Boston Gazette for the newspaper owner and did all types of print work: pamphlets, advertisements, stationery, government laws—whatever a customer needed. Ben learned to set the letters in trays, letter by letter, word by word, line by line, row by row. He dabbed and rolled the trays with ink and set them on the heavy printing press. The press forced the paper against the inked letters. As Ben grew tall and strong, he easily shouldered his share of the hard physical work lifting heavy trays of metal letters, carrying reams of paper, and handling the printing press.

BEN FOUND real joy in reading and writing—skills that could turn a lowly apprentice into a gifted printer. Printers often wrote their own articles or pamphlets and edited the work of others. Ben pored over the books in James’s small library. Few people in colonial America owned scarce and precious books. Ben discovered a way to get his hands on even more books. He befriended the apprentices of Boston’s booksellers. His friends let Ben sneak books from the shops, read them overnight, and return the volumes in the morning.

BEN FOUND real joy in reading and writing—skills that could turn a lowly apprentice into a gifted printer. Printers often wrote their own articles or pamphlets and edited the work of others. Ben pored over the books in James’s small library. Few people in colonial America owned scarce and precious books. Ben discovered a way to get his hands on even more books. He befriended the apprentices of Boston’s booksellers. His friends let Ben sneak books from the shops, read them overnight, and return the volumes in the morning.

Ben carved out time for reading and studying. At night, early in the morning, or on Sundays, when by law he should have been in church, Ben hid himself away with his books. Among his favorites were John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Roman historian Plutarch’s Lives, Daniel Defoe’s Essay on Projects, and Cotton Mather’s Bonifacius: Essays to Do Good. Ben knew Mather, a Boston minister and leading member of society.

The books gave young Ben “a Turn of Thinking.” He tried new ideas. For a time he became a vegetarian, mastering the boiling of potatoes, rice, and hasty pudding. He experimented with religious ideas such as Deism—a belief that a Superior Being created the world and then left human beings alone. He dropped his habit of arguing and contradicting people and instead adopted a new policy. Following the ideas of the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, Franklin began asking people seemingly innocent questions that slowly led them to see his side of the argument! He delighted in becoming “the humble Enquirer and Doubter.” He found this method “safest to myself & very embarrassing to those against whom I used it.”

Ben especially devoured Joseph Addison’s and Richard Steele’s essays in the Spectator, a British publication. Addison and Steele pricked society’s weaknesses through humor and wit, not by lecturing with sermons. “I thought the Writing excellent,” Ben wrote, “& wished if possible to imitate it.” He read the essays over and over. He copied them out and recopied them. He scribbled notes. He mixed up the essays’ sections, then put them back together to see how Addison and Steele organized their writings. In this painstaking manner, Ben mastered “the Arrangement of Thoughts,” the skill of engaging readers and winning them over with a clear argument.

ONLY A few men published newspapers in Boston. The papers bore the label “published by authority,” meaning the Puritan government granted permission to print. These papers played it safe, steering clear of controversy or tweaking the noses of Boston’s Puritan leaders. They mostly reprinted months-old European news and official proclamations.

ONLY A few men published newspapers in Boston. The papers bore the label “published by authority,” meaning the Puritan government granted permission to print. These papers played it safe, steering clear of controversy or tweaking the noses of Boston’s Puritan leaders. They mostly reprinted months-old European news and official proclamations.

In August 1721, James Franklin began publishing his own newspaper, the New England Courant. James’s paper was not “published by authority,” and James did not play it safe. The two- to four-page paper appeared each week, printing biting satires poking fun at many of Boston’s elite men and the Puritan church. Soon an establishment paper, the Boston Gazette and News Letter, denounced James’s efforts as a “Notorious, Scandalous Paper” full of “Nonsense, Unmannerliness … Immorality, Arrogancy … Lyes … all tending to Quarrels and Divisions” meant to corrupt the “Minds and Manners of New England.”

Hasty pudding was one of many popular ground-corn recipes in the American colonies. It was a dish that the teenage Ben learned to make for his vegetarian diet. He also ate this affordable food to save money.

MATERIALS

Adult Supervision Required

In a bowl combine 1 cup of cornmeal and 1 cup of cold water.

In a heavy saucepan bring 3 cups of water and ½ teaspoon of salt to a boil. Then, carefully whisk in the cornmeal mixture. Turn down the burner. Cook the mixture for 10 to 15 minutes over low heat, stirring once in a while.

Spoon the hasty pudding into bowls. Top with a pat of butter and your choice of maple syrup, brown sugar, molasses, or cream.

This recipe makes six to seven servings.

On Boston’s streets Ben hawked his brother’s scandalous paper, as well as some ballads he’d written himself! He shared James’s view that the Puritan government needed a bit of criticism. The Courant circulated around Boston—shared, passed along, and read not only by society’s upper crust but by “middling sorts” and the city’s artisans, as well.

But even while agreeing with James’s jabs at authority, Ben chafed at his brother’s authority over him. The apprenticeship proved difficult for Ben. Eventually he looked for any chance to shorten or break his bond.

Ben sells his ballads on the streets of Boston.

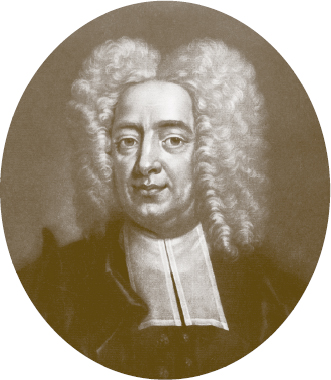

IN APRIL 1721 the most feared disease in colonial America—smallpox—arrived in Boston on a ship carrying “the speckled monster” among its crew and passengers. Many believed an angry God had sent the disease as punishment to kill and scar. Using his new paper and the smallpox crisis, James Franklin launched attacks on a leading Puritan physician and minister, Cotton Mather, and his supporters.

IN APRIL 1721 the most feared disease in colonial America—smallpox—arrived in Boston on a ship carrying “the speckled monster” among its crew and passengers. Many believed an angry God had sent the disease as punishment to kill and scar. Using his new paper and the smallpox crisis, James Franklin launched attacks on a leading Puritan physician and minister, Cotton Mather, and his supporters.

Cotton Mather had lost 2 wives and 13 of his 15 children to measles or smallpox outbreaks. Mather learned from one of his African slaves that he could prevent smallpox through a process called inoculation: a physician scratched a small amount of smallpox pus into the skin of a healthy person. Those inoculated usually caught only a mild case of smallpox. Their body’s defenses, once tested by smallpox, fought off the disease and made them safe from future outbreaks. Mather urgently promoted inoculation to save hundreds of Boston’s citizens.

But others viewed inoculation with suspicion—it did not make sense that you saved someone by giving him or her a dose of the disease. Why should Christian men trust the word of a slave, “the Way of the Heathen”? And if God sent smallpox to punish Boston, then life or death was up to God, not men—even church leaders like Mather. Did men have the right to step in to help people? Did God send cures as well as sending the disease?

The smallpox controversy offered the Courant a rousing start. The war of words in Boston’s newspapers kept Ben busy setting type and running the press. Words spiraled into violence when someone threw a bomb of gunpowder and turpentine—which failed to explode—into Mather’s house. It carried a note: “Cotton Mather, You dog. Dam you: I’ll inoculate you with this, with a Pox to you.”

In the end, however, Mather was proved correct. Half of Boston’s people caught smallpox, and 842 died. Of the 242 people inoculated, only 6 died. James’s war with Mather and others put him on a collision course with the Puritan authorities.

Cotton Mather

ON MARCH 26, 1722, the first of 16 letters appeared in the Courant penned by a respectable, middle-aged widow named Silence Dogood. In reality, 16-year-old Ben Franklin created her out of his imagination, wrote the letters, and slipped them under the Courant’s door at night. In the first letter, the widow Dogood introduced herself to her readers. Born on a ship, she recalled her father standing on the deck “rejoycing at my Birth” when “a merciless wave entered the Ship, and in one Moment carry’d him beyond Reprieve. Thus was the first Day which I saw, the last that was seen by my Father.” At the print shop, Ben listened with amusement as everyone wondered who this tart-tongued “Silence Dogood” was.

ON MARCH 26, 1722, the first of 16 letters appeared in the Courant penned by a respectable, middle-aged widow named Silence Dogood. In reality, 16-year-old Ben Franklin created her out of his imagination, wrote the letters, and slipped them under the Courant’s door at night. In the first letter, the widow Dogood introduced herself to her readers. Born on a ship, she recalled her father standing on the deck “rejoycing at my Birth” when “a merciless wave entered the Ship, and in one Moment carry’d him beyond Reprieve. Thus was the first Day which I saw, the last that was seen by my Father.” At the print shop, Ben listened with amusement as everyone wondered who this tart-tongued “Silence Dogood” was.

Ben Franklin works the printing press. Notice the type cases on the back left wall and the apprentices’ leather aprons.

Through Silence Dogood, Ben poked fun at Boston’s elite, including the students of Harvard, a place he had once hoped to attend. Dogood labeled Harvard’s students “Dunces and Blockheads” who had been admitted to the college because of their fat wallets. In return for their money, the students learned “how to carry themselves handsomely, and enter a room genteely,” and when their days at Harvard ended, they left school “as great Blockheads as ever, only more proud and self-conceited.”

In another letter the widow Dogood describes herself—a pretty good description of Benjamin Franklin, as well.

Know then, That I am an Enemy to Vice, and a Friend to Vertue. I am… a great Forgiver of Private Injuries: A Hearty Lover of the Clergy and all good Men, and a Mortal Enemy to arbitrary Government and unlimited Power. I am naturally very Jealous for the Rights and Liberties of my Country; and the least appearance of an Incroachment on those invaluable Priviledges is apt to make my Blood boil exceedingly…. To be brief; I am courteous and affable, good humour’d (unless I am provok’d), handsome, and sometimes witty, but always Sir, Your Friend and Humble Servant, Silence Dogood.

Eventually James discovered Silence Dogood’s identity. Ben’s trick riled James. He felt that Ben’s success swelled his head with vanity and encouraged disobedience. Ben recalled, “I thought he demean’d me too much in some he requir’d of me, who from a Brother expected more Indulgence,” Later, Benjamin Franklin admitted he was “too saucy and provoking” of his brother. But at the time, confident and rebellious Ben thought only about escaping.

JAMES’S BATTLES for a free press eventually landed him in jail. On June 11, 1722, he’d published an article accusing government officials of being in league with pirates smuggling along the coast. The court ordered the brothers hauled in to face a judge. The court let Ben off with a warning but imprisoned James. Ben wrote,

JAMES’S BATTLES for a free press eventually landed him in jail. On June 11, 1722, he’d published an article accusing government officials of being in league with pirates smuggling along the coast. The court ordered the brothers hauled in to face a judge. The court let Ben off with a warning but imprisoned James. Ben wrote,

During my Brother’s confinement, which I resented a good deal, notwithstanding our private Differences, I had the Management of the Paper, and I made bold to give our Rulers some Rubs in it, which my Brother took very kindly, while others began to consider me in an unfavorable Light, as a young Genius that had a Turn for Libeling and Satyr [satire].

James spent three weeks in jail. But that did not keep him out of further troubles. In February 1723 the government officially denied James the right to publish the New England Courant. James wormed his way around this by publishing the paper under Ben’s name. To do this, he and Ben signed a new and secret apprentice agreement.

But Ben knew James could never enforce the new agreement. Ben finally had the break he’d been waiting for. “I had already made myself a little obnoxious to the governing party,” he recalled, “and it was likely I might if I stay’d soon bring myself into Scrapes, [for] my indiscrete Disputations [arguments] about Religion began to make me pointed at with Horror by good People.”

But most of all, he could no longer stand working for James. In late September 1723, Ben sold a few books to raise cash, and without a word to even his parents, he broke his binding apprenticeship and ran away.