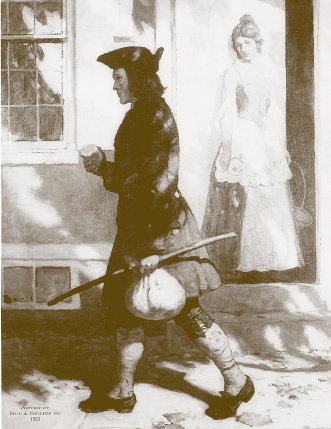

A FRIEND ARRANGED Ben’s passage on a boat out of Boston, and three days and 300 miles later he arrived in New York. He offered his services at a print shop owned by William Bradford. The man had no job for Ben, but his son living in Philadelphia might need a lad in his printing business. Ben determined to try his luck there. He endured drenching rains on shipboard, walked 50 miles, picked up another boat, and then when no winds filled the sails, helped row all the way to Philadelphia. He arrived miserable, hungry, poor, and exhausted to wander the city’s streets before falling asleep in a Quaker meetinghouse.

Ben found room and board at the Crooked Billet and crashed, spending most of his first two days in Philadelphia sleeping. Then, tidying up as best he could, Ben presented himself at Andrew Bradford’s printing shop. Like his father in New York, the younger Bradford had no employment for the runaway. He fed Ben breakfast and sent him to the only other printing shop in Philadelphia, which was owned by Samuel Keimer.

Franklin hurried to Keimer’s print shop and found him working with an “old shatter’d Press, and one small worn-out Fount of English”—not very promising to his eyes. Keimer tested Ben’s skills and eventually hired him. The teenager soon realized he knew more about printing than either Bradford or Keimer.

Ben arrives in Philadelphia and walks past Deborah Read, his future wife.

Philadelphia

IN 1681, King Charles II paid off a debt by granting William Penn vast lands in America to found a new colony. As the owner, or proprietor, of Pennsylvania (founded in 1682), Penn held great power—he could set up the colony any way he liked, decide how the legislature would run, name a governor, select the governor’s council, and pick judges. The king granted these powers in return for Penn shouldering the risk and expense of settling British subjects in America. A proprietor, however, could reap huge rewards by selling lands and collecting fees.

Penn, a member of the Society of Friends, also known as Quakers, hoped to create a haven for persecuted Quakers in his new colony. Unlike Puritan Massachusetts, Penn’s colony was recognized for its tolerance toward religion.

Penn established Philadelphia—Greek for “city of brotherly love”—where the Schuylkill River flowed into the Delaware River. Ships sailed up the Delaware River from the Atlantic Ocean to load and unload tons of cargo at Philadelphia. When Ben Franklin arrived in the 1720s, the city boasted a population of about 7,000 citizens.

Immigrants flocked to Penn’s colony, not only English but Scots, Irish, and Germans, too. Many spent their first seven years or more in America as indentured servants, bound to their masters for the payment of their ship’s passage. By the mid-1700s, over 23,000 people called Philadelphia home, making it the largest city in the 13 colonies. Philadelphia attracted scientists, artists, and craftsmen, a perfect backdrop for Ben Franklin’s talents. But Pennsylvania remained a proprietary colony. William Penn’s children inherited the ownership of Pennsylvania, and later Benjamin Franklin would clash with Penn’s powerful sons.

William Penn lands in “Pennsylvania.”

Ben lodged at the home of John Read; he especially liked his landlord’s daughter, Deborah. Never shy, Ben sought other working-class young men who shared his passion for reading and conversation. He regaled listeners with his storytelling and took pains to get along with people. He attracted people not only through his wit and good sense but also just by walking into a room. At about six feet tall—taller than the average man—and with a well-muscled body toned from years of swimming and the heavy work in a printing shop, Ben radiated strength.

BEN FRANKLIN described his full life in Philadelphia in a letter to one of his brothers-in-law, a shipmaster and trader named Robert Holmes. Captain Holmes “happened to be in company” with Pennsylvania governor Sir William Keith when Ben’s letter arrived. Amazed that a 17-year-old wrote with such style and flare, the governor deemed Ben a “young Man of promising Parts, and therefore should be encouraged.” In the 1700s a young man of low birth needed a sponsor or patron to get ahead. When the governor showed up at the print shop and invited Ben to dinner, “I was not a little surpriz’d,” recalled Ben, “and Keimer star’d like a Pig poison’d.”

BEN FRANKLIN described his full life in Philadelphia in a letter to one of his brothers-in-law, a shipmaster and trader named Robert Holmes. Captain Holmes “happened to be in company” with Pennsylvania governor Sir William Keith when Ben’s letter arrived. Amazed that a 17-year-old wrote with such style and flare, the governor deemed Ben a “young Man of promising Parts, and therefore should be encouraged.” In the 1700s a young man of low birth needed a sponsor or patron to get ahead. When the governor showed up at the print shop and invited Ben to dinner, “I was not a little surpriz’d,” recalled Ben, “and Keimer star’d like a Pig poison’d.”

Fed up with the only two printers in Philadelphia, Keith encouraged Ben to open his own print shop. He pushed the teenager to return to Boston and seek financial help from his father for the venture. His head swelled with visions of his bright future, Ben sailed to Boston and surprised his family in April 1724. Everyone welcomed the runaway home … everyone except James. Cocky Ben visited his brother’s shop, showing off a new suit, displaying a new watch, and flashing around gifts of money to James’s workers. James turned on his heel and ignored Ben, insulted by his runaway apprentice’s behavior.

Ben also visited Cotton Mather, a man whose writings he admired. The smallpox press war laid aside, Mather welcomed the younger Franklin into his library. The two continued talking while they walked down a narrow passage with a low beam running across it. Suddenly Mather cried, “Stoop, Stoop!” Ben didn’t understand until he conked his head against the beam. “He was a man,” wrote Franklin, “that never missed any occasion of giving instruction, and upon this he said to me: ‘You are young, and have the world before you; STOOP as you go through it, and you will miss many hard thumps.’”

Josiah, though pleased his son had captured the attention of Pennsylvania’s governor, turned down Ben’s request for money. Josiah even questioned Keith’s judgment in wanting to set up an inexperienced teenager in business. If Ben still desired to open his own shop in a few years, and he’d worked and saved toward his goal, then Josiah might help. Until then, his son needed to learn respect, stop poking fun at others, and grow up.

Ben stopped in New York City on the way back to Philadelphia. The governor of the colony, William Burnet, heard about the lad traveling with a trunk of books and invited him over for a chat. Apparently a well-read, clever young man made a rare and interesting character. Ben recalled, “The Govr. treated me with great civility, show’d me his library, which was a very large one, & we had a good deal of conversation about Books & Authors. This was the second Governor who had done me the Honour to take Notice of me, which to a poor Boy like me was very pleasing.”

With no money from Josiah, Governor Keith declared he’d help establish Ben’s printing business. He urged him to sail for London and buy what he needed. The governor promised to supply letters of introduction and a line of credit for Ben to purchase equipment and paper.

Governor Keith approaches Ben Franklin in Keimer’s print shop.

ON THE voyage back from Boston, calm winds held the boat off Cape Cod. Some passengers decided to fish for their supper. As a vegetarian, Ben had not eaten meat for a while, and the smell of fish frying in the pan made his mouth water. Then he remembered that, “when the Fish were opened, I saw smaller Fish taken out of their Stomachs:—Then, thought I, if you eat one another, I don’t see why we mayn’t eat you. So I din’d upon Cod very heartily … returning only now & then occasionally to a vegetable Diet.” Wasn’t it lucky, he thought, “to be a reasonable Creature, since it enables one to find or make a Reason for every thing one has a mind to do.”

While Ben waited for the big trip, he continued working at Keimer’s and courted Deborah Read. Franklin felt a “great Respect & Affection for her.” Deborah’s father had died, and her mother suggested they wait until Ben returned from England and set up his shop before jumping into marriage. “Perhaps,” Franklin later remembered, “she thought my Expectations not so well founded as I imagined them to be.” When Ben sailed, he and Deborah had “Interchang’d Promises” to marry.

In November 1724, Ben sailed for England with his friend James Ralph. He carried high hopes with him, including the hope that letters from Governor Keith lurked in the stuffed mailbags headed to London. Ben spent the voyage meeting new people, including a Quaker merchant named Thomas Denham. Denham quietly warned him not to rely too much on Governor Keith, for “no one who knew him had the smallest Dependence on him, and he laughed at the Notion of the Governor’s giving me a letter of Credit, having as he said no Credit to give.”

Unfortunately for Ben, this proved true. The mailbag held no letters. “He wished to please every body,” he wrote of Keith, “and having little to give, he gave expectations.” But a young man could not live on expectations. Ben needed a job.

LONDON DWARFED both Boston and Philadelphia with a population of over half a million people. Many were like Ben, new arrivals crowding into the old city’s narrow lanes and busy streets. London bustled with merchants and shopkeepers, traders, artisans, and craftsmen. Below these comfortable skilled workers on the social ladder clung a mass of poor people: beggars, sailors, street vendors, servants, and laborers. At the very tip of society the king and his aristocrats lived in luxury and richness unimaginable in the colonies. They spent more on a single banquet than an American might earn in a lifetime.

LONDON DWARFED both Boston and Philadelphia with a population of over half a million people. Many were like Ben, new arrivals crowding into the old city’s narrow lanes and busy streets. London bustled with merchants and shopkeepers, traders, artisans, and craftsmen. Below these comfortable skilled workers on the social ladder clung a mass of poor people: beggars, sailors, street vendors, servants, and laborers. At the very tip of society the king and his aristocrats lived in luxury and richness unimaginable in the colonies. They spent more on a single banquet than an American might earn in a lifetime.

Ben quickly found work at a famous London printing house. He and James Ralph lodged together and freely spent their money attending plays and other amusements. Ben loved hanging out at coffee shops, listening to the conversations. He scribbled letters introducing himself and seeking introductions to famous and interesting people. One man promised to introduce him to the famous scientist Sir Isaac Newton—but the meeting never took place.

James Ralph admitted he never meant to return home to his wife and child in the colonies. Ben too caught the wave of unfaithfulness and forgot his engagement to Deborah, “to whom I never wrote more than one letter, & that was to let her know I was not likely soon to return.” He hung out with “low women.”

As money flew from his pockets in amusements and loans to Ralph, Ben realized he’d better shape up. He began work at one of the best printing houses in London, moved to cheaper lodgings, and slashed his rations. For breakfast he dug into hot-water gruel spiced with pepper, breadcrumbs, and a bit of butter. He downed half an anchovy, bread and butter, and a half-pint of ale for supper. He worked hard and impressed his employer and fellow workers, who called him the “Water American” because he refused to spend all his hard-earned wages on ale.

One young man hired Ben to teach him how to swim. Other gentlemen expressed curiosity, for few people, even sailors, could swim. One day, remembered Franklin, “I stript & leapt into the River, & swam from near Chelsea to Blackfryars, performing on the Way many Feats of Activity both upon & under Water, that surpriz’d and pleas’d those to whom they were Novelties.” He even considered traveling Europe to teach swimming and perform demonstrations.

But one day Ben met his friend from the ship, Mr. Denham, who encouraged Ben to return to Philadelphia and work for him as a shop clerk. After 18 months in London, the thought of home seemed sweet. He agreed to Denham’s offer of assistance, and on July 23, 1726, Ben Franklin left England for Philadelphia.

The printing press Ben Franklin trained on in London.

ON THE 11-week voyage home, Ben kept a journal, noting his observations of rainbows, dolphins, seaweed, crabs—all things of air and sea. More importantly, the 20-year-old mulled over his life and determined he needed a “Plan For Future Conduct.” “Let me therefore make some resolutions,” he wrote, “and form some scheme of action, that henceforth I may live in all respects like a rational creature.”

ON THE 11-week voyage home, Ben kept a journal, noting his observations of rainbows, dolphins, seaweed, crabs—all things of air and sea. More importantly, the 20-year-old mulled over his life and determined he needed a “Plan For Future Conduct.” “Let me therefore make some resolutions,” he wrote, “and form some scheme of action, that henceforth I may live in all respects like a rational creature.”

Ben penned a few basic rules. He would be “extremely frugal … till I have paid what I owe.” He would not lose focus “by any foolish project of suddenly growing rich.” Hard work and patience would carry him through to a comfortable life. He vowed “to speak truth in every instance; to give nobody expectations that are not likely to be answered.” He promised to “speak ill of no man whatever.”

Denham died shortly after the return to Philadelphia, and Ben returned to Keimer’s printing house. There he managed and trained the other workers. He became the first person in America to make type from a mold. When Keimer received a job printing money for the colony of New Jersey, Ben designed and engraved the copperplates so ornately that the money could not easily be counterfeited.

The contrast between untidy, grouchy Keimer and young, energetic Franklin, radiating charm and skill, struck print shop customers. People invited Ben to their homes and introduced him to their friends. His web of friends spread and became of “great Use to me, as I occasionally was to some of them.”

FRANKLIN FINALLY had enough of making Keimer look good. In 1728, he and another Keimer employee, Hugh Meredith, opened their own printing business. Meredith’s father supplied the money. They rented a house for their shop, and to help pay rent they leased space to a glazier (glass worker). The glazier’s wife provided Ben’s meals.

FRANKLIN FINALLY had enough of making Keimer look good. In 1728, he and another Keimer employee, Hugh Meredith, opened their own printing business. Meredith’s father supplied the money. They rented a house for their shop, and to help pay rent they leased space to a glazier (glass worker). The glazier’s wife provided Ben’s meals.

Within hours after opening they had their first customer. Ben worked backbreaking long hours, sometimes till 11:00 at night or later, to build his business. “And this industry,” he wrote, “visible to our Neighbours began to give us Character and Credit.”

Ben worked to woo a few top printing jobs away from Andrew Bradford. When Bradford printed an address from the governor to the Pennsylvania legislature, Franklin thought the work coarse and blundering. He reprinted the address “elegantly & correctly” and sent a copy to every House member. The next year the House voted to give his print shop their government business.

Ben supported the idea that Pennsylvania needed more paper money in circulation to boost the economy. He wrote a pamphlet titled A Modest Enquiry into the Nature & Necessity of a Paper Currency. Who soon won the job for printing the new money? Ben called the profitable work “a great Help to me.—This was another Advantage gain’d by my being able to write.”

Ben took care not only to be hard working,

… but to avoid all Appearances of the Contrary. I drest plainly; I was seen at no Places of idle Diversion; I never went out a-fishing or shooting… and to show that I was not above my Business, I sometimes brought home the Paper I purchas’d at the Stores, thro’ the Streets on a Wheelbarrow. Thus being esteem’d an industrious thriving young Man, … I went on swimmingly.

People noticed Ben at work when they went home, and he was already in his shop before most were out of bed the next day.

One neighbor commented, “The industry of that Franklin is superior to anything I ever saw of the kind.” Another man noted, “Our Ben Franklin is certainly an Extraordinary Man in most respects, one of a singular good Judgment, but of Equal Modesty.” No wonder people rewarded him with their business.

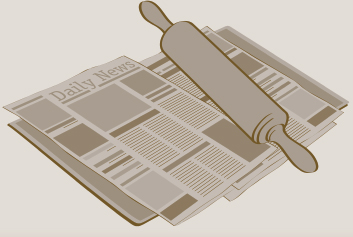

MEANWHILE, KEIMER’S shop lost business and folded—leaving Franklin and Bradford as Philadelphia’s sole printers. Franklin jumped at the chance to buy Keimer’s failing paper, the Pennsylvania Gazette. The only other paper in town belonged to Bradford, which Franklin dismissed as “a paltry thing, wretchedly managed, no way entertaining; and yet was profitable to him.” With his talent for wit and writing, he knew he could do better. His first issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette appeared in early October 1729 with a jab at Bradford’s paper. Franklin announced: “There are many who have long desired to see a good newspaper in Pennsylvania.”

MEANWHILE, KEIMER’S shop lost business and folded—leaving Franklin and Bradford as Philadelphia’s sole printers. Franklin jumped at the chance to buy Keimer’s failing paper, the Pennsylvania Gazette. The only other paper in town belonged to Bradford, which Franklin dismissed as “a paltry thing, wretchedly managed, no way entertaining; and yet was profitable to him.” With his talent for wit and writing, he knew he could do better. His first issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette appeared in early October 1729 with a jab at Bradford’s paper. Franklin announced: “There are many who have long desired to see a good newspaper in Pennsylvania.”

The Pennsylvania Gazette carried not only news and reports but also lively essays and letters from readers. Ben wrote editorials and many of the paper’s amusing columns. In one editorial he claimed that Bradford could freely reprint articles from the Gazette, but “he is desired not to date his paper a day before ours lest readers should imagine we take from him, which we always carefully avoid.” Franklin’s essays presented his views through such made-up characters as Anthony Afterwit, Alice Addertongue, and Celia Single. Ben also wrote many of the “letters from readers,” taking every opportunity to praise himself and his paper and knock down his competitor! But overall, he kept his paper free of controversy, taking care not to offend potential customers.

Ben Franklin pushes a wheelbarrow full of paper through Philadelphia streets.

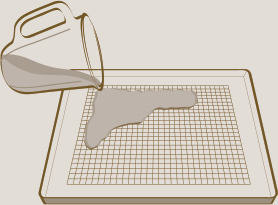

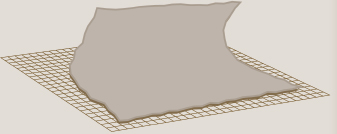

In colonial times, paper was most often made with old rags, creating a thick, heavy paper. As Ben’s business grew, his wife, Deborah, collected rags for recycling into paper. He eventually owned nearly 20 paper mills.

MATERIALS

Adult supervision required

Tear the scrap paper into small bits and put it into the measuring cup—½ cup of torn scraps will make one sheet of paper.

Add 2 cups of hot water to the paper bits. Pour the water and paper bits into a blender. Blend the mixture into a thick pulp.

Stack sheets of newspaper on a table or counter. Put the screen in the flat pan. Pour the pulp over the screen; then slide the screen around to make sure it is covered evenly with the pulp.

Lift the screen out of the pan, keeping it flat, with the pulp side up. Lay the screen on the stack of newspaper. Cover it with an old dish towel and some more newspapers. Throw any leftover pulp in the trash. Do not pour it down the sink.

Take a rolling pin (you can also use a tin can) and gently roll it over the newspaper and towel. This flattens the pulp and helps squeeze out some of the liquid.

Carefully take the newspaper and towel off the pulp/screen. Put the screen on some fresh blotting paper and let it dry. The pulp can take 12 to 24 hours to dry and turn into paper. If it is a sunny day, you can put it in a protected place outside to speed the drying.

When the paper is dry, carefully peel it off the screen. You now have a thick, heavy sheet of paper to use. You can add thread, glitter, or pressed flowers or leaves to the pulp to make decorative paper.

Ben’s partner, Hugh Meredith, was seldom sober and was a poor printer. His bad habits jeopardized Franklin’s hard work. With the help of friends, he bought Meredith out of the business, leaving Franklin with a pile of debts. Slowly he whittled down his debt and expanded his business. He opened a little stationery shop and began making paper.

Bradford’s print shop, however, retained one great advantage: Bradford ran the post office. And some customers thought this meant Bradford had more access to news and the ability to distribute advertisements to customers.

BEN DECIDED marriage offered the best way to control his “hard-to-be-govern’d Passion of Youth.” Also, many young men advanced their position in society by marrying young women with money. Franklin discovered, however, that his growing reputation as a businessman did not guarantee parents favored his courtship of their daughters. “The Business of a Printer being generally thought a poor one, I was not to expect Money with a Wife,” he wrote. He turned his attentions back to Deborah Read, whom he’d left waiting when he’d gone to London.

BEN DECIDED marriage offered the best way to control his “hard-to-be-govern’d Passion of Youth.” Also, many young men advanced their position in society by marrying young women with money. Franklin discovered, however, that his growing reputation as a businessman did not guarantee parents favored his courtship of their daughters. “The Business of a Printer being generally thought a poor one, I was not to expect Money with a Wife,” he wrote. He turned his attentions back to Deborah Read, whom he’d left waiting when he’d gone to London.

Deborah had given up on Ben’s promises. She had married someone else, only to discover her husband likely had a wife already living in England. Deborah left him and returned to her mother. The man eventually sailed for the West Indies and reportedly died—but no one knew for sure. Franklin remarked, “Our mutual Affection was revived,” and on September 1, 1730, he and Deborah began living together as husband and wife.

Deborah, poor and barely able to read and write, offered Ben little help in his climb up the social ladder. When Philadelphia’s gentry invited him to their homes, Deborah did not go. But she proved a hardworking partner, running their home, helping in the shop, and keeping a keen eye on every penny spent—qualities he greatly admired.

Deborah Read Franklin

Not long after their marriage, Franklin introduced a new member into their family—William, a baby son he’d had with an unknown woman. Franklin doted on the boy and expected Deborah to raise him. Deborah gave birth in 1732 to a baby boy named Francis Folger (called Franky), who died at age four of smallpox. His little boy’s death crushed Franklin, who’d meant to have the child inoculated against the disease but had not gotten around to it. He described his son with a few words on the little boy’s gravestone: “The delight of all who knew him.”

Ben Franklin works at the first lending library.

THROUGH INTENSIVE reading and conversation Ben Franklin developed his own views of religion. He firmly believed that “the most acceptable Service of God was the doing of Good to Man.” He also believed that one man “may work great Changes, and accomplish great Affairs among Mankind, if he first forms a good Plan.”

THROUGH INTENSIVE reading and conversation Ben Franklin developed his own views of religion. He firmly believed that “the most acceptable Service of God was the doing of Good to Man.” He also believed that one man “may work great Changes, and accomplish great Affairs among Mankind, if he first forms a good Plan.”

In 1727, while still working at Keimer’s shop, Ben gathered a group of like-minded young men together for weekly meetings of the Leather Apron Club. A leather apron, stained, scratched, and worn thin, served as a badge for hardworking craftsmen and artisans. The group included surveyors, clerks, a glass worker, a shoemaker, a cabinetmaker, and others.

Eventually renamed the Junto, Ben’s club discussed politics, science, morals, and schemes for bettering society. Each week members exchanged ideas and information aimed at helping one another get ahead in business. Junto members pooled their books together for everyone to share. Ben, a great talker used to “prattling, punning, and joking,” quickly realized he learned far more “by use of the ear than of the tongue.”

In 1731 Ben Franklin drew up a plan for the Junto proposing the first lending library in the colonies. Franklin described his plan as “my first Project of a public Nature.” For a fee subscribers could check out books and read them. The money from the fees covered the cost of buying new books. Years later, as numerous libraries dotted American towns, Franklin noted with pride that the libraries had “improv’d the general Conversation of the Americans, [and] made the common Tradesmen and Farmers as intelligent as most Gentlemen from other Countries.”

MATERIALS

Adult supervision required

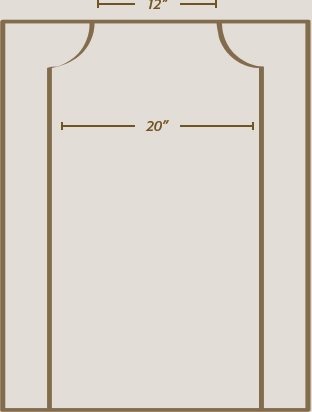

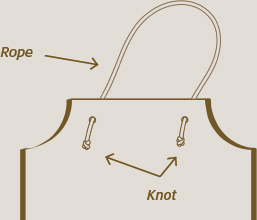

Use scissors to cut fabric into an apron shape (see drawing)

Lay the fabric facedown on a table. Lay a strip of Stitchwitchery along the hem and sides. Fold the fabric over the strip. Iron the fabric. The heat from the iron will seal the hem.

Cut a length of rope about 36 inches long. With adult help, use the nail to poke two holes at the top of the apron large enough for the rope to pass through (see drawing). Pass the rope through the holes, forming a loop for your head. Knot the rope ends in the front of the apron.

Measure and cut a length of rope to tie around your waist. Now you have a craftsman’s apron to work on your own projects.

By his mid-twenties, Ben Franklin owned a thriving printing and publishing business, had married, and had immersed himself in public improvements. He had already advanced further than anyone would have dreamed for a working-class poor boy. But his keen eye for opportunity flung open more doors that he would soon march through.

ANYTHING MIGHT be discussed at a Junto meeting, from “What is wisdom?” to whether or not indentured servants made the colonies more prosperous. Franklin wrote a list of 24 questions for members to keep in mind. A few examples:

What new story have you lately heard agreeable for telling in conversation?

Hath any citizen in your knowledge failed in his business lately, and what have you heard of the cause?

Have you lately heard of any citizen’s thriving well, and by what means?

Do you know of any fellow citizen who had lately done a worthy action deserving praise and imitation? Or who has committed an error proper for us to be warned against and avoid?

Hath any deserving stranger arrived in town since last meeting that you heard of? And whether you think it lies in the power of the Junto to oblige him or encourage him as he deserves?

In what manner can the Junto… assist you in any of your honorable designs?

For Ben, good works and improving the lives of others was of utmost importance. Gather friends and family and start your own Junto. Have monthly meetings to plan what to do. Brainstorm ideas and keep notes of your plans. Some suggestions:

After you decide on an idea, create a plan of action to make it happen. Contact people to volunteer or find out how you can make a donation to a charity. Ben Franklin knew every little bit counts to make the world a better place!