BENJAMIN FRANKLIN stayed on in Paris at the end of the American Revolution. The Congress had not recalled him, so he remained, enjoying life in France while he continued diplomacy on America’s behalf. Franklin’s reputation in Europe helped gain recognition for the United States as it sought its place among the nations of the world. While still in Paris, Franklin led negotiations for treaties between the new United States of America and Prussia and Sweden.

Benny returned to Passy after four years at school in Geneva, Switzerland. Franklin taught his grandson to swim, and Temple taught his 14-year-old cousin how to fence and dance. Benny also began learning how to use Franklin’s printing press at Passy.

John Adams, back in France with his wife, Abigail, remained amazed at France’s love for Franklin. The French women’s “unaccountable passion for old age” especially shocked Adams, who noted how they buzzed around Franklin. Franklin seemed to have a crush on Anne-Catherine Helvétius, a widow who hosted salons with the most entertaining, witty, and brilliant people in Paris. Franklin, half in play, often asked Madame Helvétius to marry him. The Adamses thought the woman bold and loose. She threw her arms about people and sprawled in an unladylike manner on the sofa, “where she shew more than her feet,” wrote Abigail in September 1784.

The flood of Europeans to America, which they viewed as a place to get rich quickly, continually annoyed Franklin. For his taste, too many of them “value themselves and expect to be valued by us for their Birth or Quality, though I tell them those things bear no Price in our Markets.” If Franklin had his way, only people with a “useful Trade or Art by which they may get a living” would sail across the Atlantic.

Finally, fed up with repeating himself, Franklin wrote a pamphlet in February 1784 that was packed with information and titled Those Who Would Remove to America. Franklin warned that while America’s acres might be cheap, the land required hard work to make a living. America, he said, was the “Land of Labour.” And no cushy government jobs, like the elite expected in European nations, waited for them in America. In America, wrote Franklin, people did not ask, “What IS he? but What can he DO?”

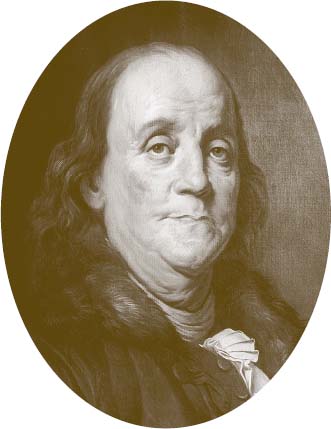

A copy of Charles Wilson Peale’s portrait of Franklin, around 1785-87. Peale’s portrait clearly shows Franklin’s bifocals.

ON JUNE 4, 1783, Franklin witnessed the first successful attempts by humans to soar above the earth. Two brothers, Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier, tested an unmanned hot-air balloon. In August, Franklin along with about 50,000 others watched another unmanned balloon flight by Jacques Charles. This balloon used hydrogen gas (discovered in 1766) instead of hot air to lift it into the sky. The silk balloon, which measured 12 feet in diameter, landed in a village 15 miles away! “It diminish’d in Apparent Magnitude as it rose,” Franklin wrote to a friend at the Royal Society, “till it enter’d the Clouds, when it seemed to me scarce bigger than an Orange, and soon after became invisible, the Clouds concealing it.”

ON JUNE 4, 1783, Franklin witnessed the first successful attempts by humans to soar above the earth. Two brothers, Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier, tested an unmanned hot-air balloon. In August, Franklin along with about 50,000 others watched another unmanned balloon flight by Jacques Charles. This balloon used hydrogen gas (discovered in 1766) instead of hot air to lift it into the sky. The silk balloon, which measured 12 feet in diameter, landed in a village 15 miles away! “It diminish’d in Apparent Magnitude as it rose,” Franklin wrote to a friend at the Royal Society, “till it enter’d the Clouds, when it seemed to me scarce bigger than an Orange, and soon after became invisible, the Clouds concealing it.”

A balloon craze swept France, and Franklin, too. In September the Montgolfiers staged another flight at Versailles in front of the royal family and 130,000 Parisians. On board traveled the first balloon passengers—a sheep, a duck, and a rooster. All creatures landed safely but, unfortunately, could not report about their experiences.

The first manned flight occurred on November 21. The two men onboard waved their hats to spectators, including Franklin. The spectators “had great Pleasure in seeing the Adventurers go off so cheerfully, and applauded them,” wrote Franklin, “but there was at the same time a good deal of Anxiety for their Safety.” The balloon traveled 20 minutes before a gentle landing, to the popping of champagne corks. The next day the Montgolfiers visited Franklin at his home, where he signed an official certificate of the historic manned flight. “Nothing is wanted,” wrote Franklin, “but some light handy Instruments to give and direct Motion.”

Two weeks later 400,000 people crushed together to watch another manned flight. “Never before was a philosophical (science) experiment so magnificently attended,” gushed Franklin. A wicker basket beneath the balloon held a small table so the three passengers could make notes and for the first time describe what the earth and clouds looked like from high above.

The Montgolfiers’ flight, September 19, 1783, at the Palace of Versailles.

FRANKLIN BELIEVED that Americans were growing larger than Europeans. At a dinner party in Paris he asked everyone at the table to stand up. Every American towered over the French citizens. One guest recalled, “There was not one American present who could not have tost out of the Windows any one or perhaps two of the rest of the Company.”

“A few months [ago] the idea of Witches riding thro’ the Air upon a Broomstick, and that of Philosophers upon a Bag of Smoke, would have appear’d equally impossible and ridiculous,” noted Franklin. For centuries man had dreamed of flying—and now it had come true! In January the first British ballooning attempts took place.

Surprised citizens in a French village inspect a fallen balloon.

THE FIRST part of Franklin’s autobiography covered his early life. He’d written it in England during a time of uncertainty and frustration. Franklin gave the pages to his friend Joseph Galloway. But Galloway, a loyalist during the war, fled America. The writings turned up in the hands of Mrs. Galloway’s lawyer, Abel James. James urged Franklin to continue the work, so “useful & entertaining not only to a few, but to millions.” An English friend seconded these thoughts. “Your life is so remarkable, that if you do not give it, somebody else will,” wrote Benjamin Vaughan to Franklin. Just think, said Vaughan, how Franklin’s words might inspire a future generation of great and wise men.

THE FIRST part of Franklin’s autobiography covered his early life. He’d written it in England during a time of uncertainty and frustration. Franklin gave the pages to his friend Joseph Galloway. But Galloway, a loyalist during the war, fled America. The writings turned up in the hands of Mrs. Galloway’s lawyer, Abel James. James urged Franklin to continue the work, so “useful & entertaining not only to a few, but to millions.” An English friend seconded these thoughts. “Your life is so remarkable, that if you do not give it, somebody else will,” wrote Benjamin Vaughan to Franklin. Just think, said Vaughan, how Franklin’s words might inspire a future generation of great and wise men.

How could Franklin resist these arguments? He began writing, this time creating a plan for achieving happiness and success, different from the chatty stories of the biography’s first half. He believed that his successful mission in France and the treaty with Great Britain had proved his theory that a few men of good judgment and common sense could “work great Change, and accomplish great Affairs among mankind.”

IN 1778 a German native named Friedrich Mesmer arrived in Paris. Mesmer claimed he had powers to control a healing magnetic force, allowing him to cure paralysis, eye troubles, blocked intestines, anxiety, and depression. By “mesmerizing,” or touching patients with his hands or an iron wand or rod, Mesmer removed a blockage that stopped the flow of the body’s “magnetic fluids.” At Mesmer’s touch, patients trembled and convulsed, the blockage moved, the magnetic fluid flowed, and the patient recovered. Mesmer opened several clinics and also held healing gatherings for entire rooms of patients.

IN 1778 a German native named Friedrich Mesmer arrived in Paris. Mesmer claimed he had powers to control a healing magnetic force, allowing him to cure paralysis, eye troubles, blocked intestines, anxiety, and depression. By “mesmerizing,” or touching patients with his hands or an iron wand or rod, Mesmer removed a blockage that stopped the flow of the body’s “magnetic fluids.” At Mesmer’s touch, patients trembled and convulsed, the blockage moved, the magnetic fluid flowed, and the patient recovered. Mesmer opened several clinics and also held healing gatherings for entire rooms of patients.

When compared with typical “heroic” treatments of the day—bleeding, purging, blistering, harsh tonics, and electrical shocks—Mesmer’s treatments seemed gentle. He even had Franklin’s armonica played during treatments for the otherworldly sound. The ill and infirm flocked to Mesmer’s mass healings. He soon trained other “mesmerists,” and branches of his clinics popped up all over France.

But Mesmer had not won over France’s scientists or physicians. His followers asked why the idea of a magnetic flow in the body should seem stranger than Newton’s claims of gravity or Franklin’s claim to pull lightning from the skies. Temple belonged to one of Mesmer’s “Harmony Societies.”

Franklin believed many people “are never in health, because they are fond of Medicines.” They ruined their health through this love of treatments. “If these people can be persuaded to forbear their Drugs in Expectation of being cured by one of the Physician’s Fingers or an Iron Rod pointing at them, they may possibly find good Effects tho’ they mistake the Cause.”

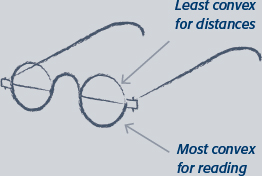

AS FRANKLIN aged, his eyesight grew worse. He constantly switched between two pairs of glasses, one to see close-up and one to see at a distance. One evening at dinner he grew especially frustrated. He either couldn’t see his plate or couldn’t read the expressions of the other guests across the table. So he devised a solution to his problem.

Franklin cut the lenses of two separate pairs of glasses into semicircular halves. Then he combined the lenses. “By this means, as I wear my spectacles constantly, I have only to move my Eyes up or down as I want to see distinctly far or near, the proper glasses being always ready,” he wrote to a friend. Even Franklin was surprised at this easy solution. “If all the other Defects and Infirmities,” he wrote, “were as easily and cheaply remedied, it would be worth while for Friends to live a good deal longer.” Bifocal lenses are still in use today.

Franklin drew a rough sketch, like this one, of his bifocals in a letter to a friend.

In 1784 the Academy of Sciences set up a committee to investigate Mesmer’s claims. Franklin served as a member and offered his garden at Passy to test Mesmer’s theories. Blindfolded patients thought mesmerists treated them, but they were actually treated by committee members using Mesmer’s words and gestures. The patients claimed they felt the magnetic fluids flowing. Meanwhile, real mesmerists “magnetized” subjects without their knowledge. These patients felt no effect of the magnetic fluids. The committee kept a boy in Franklin’s house while a mesmerist magnetized a tree. The boy was told to find the tree. He went into convulsions and passed out after hugging a non-magnetized tree.

The committee concluded that no magnetic fluid existed and that Mesmer’s effects came from the patient’s imagination or from copying others. They labeled Mesmer a fraud who preyed on people, especially women, who were seen as more emotional and weak. A cartoon showed Franklin leading a charge of committee members waving their report as Mesmer fled on a broomstick.

Magnetism, however, was “a science which is still brand new” that needed further study, as well as “the influence of the psychological on the physical,” reported the committee. Mesmer left Paris in 1785 and roamed Europe defending his methods. The word mesmerize, meaning to hypnotize, comes from Friedrich Mesmer’s name and treatment.

IN A January 1784 letter to Sally, Franklin humorously expressed his views about the bald eagle serving as an emblem to the country. “I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen as the Representative of our Country; he is a Bird of bad moral character; he does not get his living honestly” but instead steals food from others. “For in Truth, the Turk’y is in comparison a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America. Eagles have been found in all Countries, but the Turk’y was peculiar to ours…He is, though a little vain and silly, … a Bird of Courage” who “would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards, who should presume to invade his FarmYard with a red Coat on.”

IN MAY 1785, Franklin finally heard from Congress that his mission was over. They had named Thomas Jefferson America’s new minister to France. Franklin began packing for the journey back to Philadelphia, having spent nine happy years in Paris. “If I had no country of my own it would be Paris where I should like to finish out my days,” he wrote, “but I want to enjoy for a moment the pleasure of seeing my fellow citizens free and ready for all the happiness I wish them.”

IN MAY 1785, Franklin finally heard from Congress that his mission was over. They had named Thomas Jefferson America’s new minister to France. Franklin began packing for the journey back to Philadelphia, having spent nine happy years in Paris. “If I had no country of my own it would be Paris where I should like to finish out my days,” he wrote, “but I want to enjoy for a moment the pleasure of seeing my fellow citizens free and ready for all the happiness I wish them.”

While packing, Franklin opened the door to a young man from Holland who had come to show evidence from his electrical experiments to the Academy of Sciences. Martinus van Marum worked at a museum with a large “electrical friction machine” the young man had designed. It took four people to crank, and it generated electrical sparks two feet long with veinlike branches much like lightning.

“This venerable old man, whose presence inspired me with such profound respect, made me sit down beside him,” wrote van Marum. Franklin studied the plans and images van Marum had brought. Did this accurately show electrical exchanges? Franklin asked. It did. “This then proves my theory of a single electric fluid, and it is now high time to reject the theory of two sorts of fluid.” Then Franklin excused himself to finish packing.

Out of the previous 27 years, Franklin had spent only three and half years in America. His friends in America were dying off. “I have been so long abroad,” he wrote to his son William, that “I should now be almost a Stranger in my own Country.” He’d been hurt by challenges to his patriotism from fellow commissioners and members of Congress. Some Americans wondered whether Franklin’s loyalties lay more with France or his new nation.

Franklin wanted Temple, the “Son who makes up to me my Loss by the Estrangement of his Father,” to deliver the peace treaty to Congress. But the honor went to a friend of John Adams. Franklin asked Congress to name his 24-year-old grandson to a new commission seeking trade treaties with Europe. Most of all he wished to see Temple named as his replacement as the American minister to France, or to another European nation. But Congress snubbed Temple and, through him, Franklin.

We’ve all seen the eagle on the national seal. A banner held in his beak proclaims E Pluribus Unum (“Out of Many, One”), a motto that Franklin proposed. The eagle’s talons grasp an olive branch with 13 leaves on one side and 13 arrows on the other. The number 13 represents the original 13 states. A shield with stripes covers the bird’s body. But what if Franklin’s jest had won out?

MATERIALS

Adult supervision required

Cut a sheet of tag board or cardboard with scissors or a utility knife into the shape you want. Spray-paint the background color of your choice if using cardboard.

Using a pencil, draw your design for a national seal using the turkey. Don’t forget to add symbols and mottos.

Color your seal with paint. For a bit of shine, glue on some gold or silver glitter.

One man wrote to Adams that when Franklin saw how Temple was passed over, Franklin “will have no Reason to Suppose that his Conduct is much approved.” The new minister to France, however, Thomas Jefferson, admired Franklin greatly. He wrote James Monroe in Congress, “Europe fixes an attentive eye on your reception of Doctor Franklin.” This will speak to Europe “as an evidence of the satisfaction or dissatisfaction of America with their Revolution.”

FRANKLIN SPENT decades recording and studying weather. Besides his work with lightning, one of the things he observed was that storms typically moved from west to east. He believed a storm’s path could be plotted. Franklin made some of the first weather forecasts and printed them in Poor Richard: An Almanack. Franklin also discussed with other scholars the effects on weather of cutting down forests. They believed “cleared land absorbs more heat and melts snow faster.”

Sobbing friends saw the nearly 80-year-old Franklin off as he sailed to England. There he met old friends one last time before embarking on his final voyage across the Atlantic. He also saw William. The meeting ended coldly, with no peace rekindled between father and son.

FRANKLIN SPENT seven weeks at sea. He booked an extra-large cabin so he’d have room to write and make his observations. For thirty years he had read about whaling ships and talked to sea captains, and he had known that ships traveled faster on some courses than others. During his 1776 voyage he’d tracked the daily air and water temperatures, testing the phenomenon of a warm ocean current called the Gulf Stream.

FRANKLIN SPENT seven weeks at sea. He booked an extra-large cabin so he’d have room to write and make his observations. For thirty years he had read about whaling ships and talked to sea captains, and he had known that ships traveled faster on some courses than others. During his 1776 voyage he’d tracked the daily air and water temperatures, testing the phenomenon of a warm ocean current called the Gulf Stream.

Franklin believed that the Gulf Stream originated in shallows off the Gulf of Florida. There the warm waters shot through the narrow Straits of Florida. The narrowness of the straits sped up the current, which then flowed into the Atlantic and headed north. This warm Gulf Stream moved faster than the rest of the water.

As the first person to put together all the bits and pieces known about the Gulf Stream, Franklin devised an instrument to measure the water temperature at a depth below 100 feet. He spent the 1785 voyage figuring out the location, width, and depth of the Gulf Stream. In 1786 he mapped his conclusions. Two hundred years later, images taken from space showed that Franklin’s map very accurately followed the Gulf Stream.

ON SEPTEMBER 14, 1785, Franklin’s ship docked in Philadelphia. The city met him with ringing bells and crowds of well-wishers, an “affectionate Welcome” beyond the old man’s expectations. Booming Philadelphia boasted a population of 40,000—tiny when compared with that of London or Paris, but at the time it was the largest city in America. Thanks in large part to Benjamin Franklin’s efforts, the city led the nation in arts, medicine, and sciences as well as luxuries such as libraries and paved streets.

ON SEPTEMBER 14, 1785, Franklin’s ship docked in Philadelphia. The city met him with ringing bells and crowds of well-wishers, an “affectionate Welcome” beyond the old man’s expectations. Booming Philadelphia boasted a population of 40,000—tiny when compared with that of London or Paris, but at the time it was the largest city in America. Thanks in large part to Benjamin Franklin’s efforts, the city led the nation in arts, medicine, and sciences as well as luxuries such as libraries and paved streets.

DURING RENOVATIONS Franklin discovered that his house had been struck by lightning sometime in the past. His 1752 lightning rod, though bent and blackened, had protected his home from damage. After all that time, he wrote to a friend in 1787, “the invention has been of some use to the inventor.”

One of the tools Franklin used to study weather was a barometer, first used in the 1600s. The instrument measures air pressure.

MATERIALS

Blow up a balloon; then let the air out. Once it is stretched, cut off a large part of the balloon, as shown.

Stretch the balloon top over the open top of the can. You will need another person to hold the can for you. Stretch a large rubber band around the balloon to hold the balloon tightly in place. It will look like a drum.

Tape a pin or toothpick onto the end of a drinking straw. Lay the straw on top of the balloon and tape it onto the balloon.

Take the barometer outside to a covered spot. A few times a day take a reading from your barometer. Hold the spiral notebook up and see where the pin/toothpick points on the lines. Make a mark.

Make notes about the weather conditions when you check the barometer readings. What do you notice?

What is happening? When air pressure is higher, it pushes on the balloon, making the balloon go down and the straw go upward on the lines on the paper. When the air pressure decreases, the pressure on the balloon is less and the reading will be lower. Usually, low air pressure means rain or clouds. When the barometer drops, a storm may be coming. High pressure usually means clear weather.

Franklin arrives home and greets Sally and her husband. A sedan chair waits to carry him to his house.

Franklin moved into the Market Street house with Sally’s growing family of six children, now that Benny had returned. There was an older boy named Willy and “four little prattlers who cling about the knees of their grandpapa and afford him great pleasure,” wrote Franklin. Benny enrolled at the school founded by his grandfather, then called the University of the State of Pennsylvania. He graduated in 1787 and became a printer and publisher like his grandfather.

Eventually the house proved too crowded. Franklin had a three-story addition put on: a dining room that seated 24 guests, more bedrooms, and a library he filled with 4,000 books and assorted musical instruments. The old man enjoyed overseeing the work of numerous carpenters, painters, bricklayers, and stonecutters. Franklin spent his time inventing things, such as a long “grabber” to reach books on high shelves. He read and played cards and cribbage with friends.

Once more, however, Pennsylvania sent Franklin to work in the assembly and as a member of the state’s executive council. His desire to help, and to earn the good opinion of his fellow citizens, drove him on even when his body protested it was time to retire. He suffered with gout, painful bladder, and kidney stones, and was often tired. He wrote to a friend in February 1786, “You see that old as I am, I am not yet grown insensible, with respect to Reputation.”

MATERIALS

Adult supervision required

Paint your dowel rod a color or stain it with wood stain. Let it dry.

Make a ball out of the modeling clay, two to three inches in diameter. Fit the ball onto the top of the dowel rod. You can leave it round or flatten it a bit. Use a checker or stamp to put a design on the top if you want. Carefully take the ball off the dowel rod. Bake the clay in the oven following the package directions.

After the clay has baked, hardened, and cooled, paint the clay with a design using a fine brush.

After the paint dries, glue the clay ball onto the dowel rod and you have an 18th-century walking stick!

Franklin as an old man.

EVEN WITH all the accomplishments of his long life Franklin hoped to “finish handsomely.” “Being now in the last Act, I begin to cast about for something fit to end with,” he wrote to George Whitefield. Franklin’s new mission became the abolition of slavery. He had traveled for a lifetime to reach this decision.

EVEN WITH all the accomplishments of his long life Franklin hoped to “finish handsomely.” “Being now in the last Act, I begin to cast about for something fit to end with,” he wrote to George Whitefield. Franklin’s new mission became the abolition of slavery. He had traveled for a lifetime to reach this decision.

Franklin had grown up in a world that accepted slavery without a second thought. He owned and bought slaves for thirty years. He printed notices about runaway slaves and servants and the auction of slaves in the Pennsylvania Gazette. Like most white people of the time, Franklin felt that Africans lacked the “natural understanding” to be educated.

One of Franklin’s first concerns was not for the enslaved people but how slavery affected the white owners. Since the white people had slaves to do the work, the masters and their families grew weak and “enfeebled.” White children, he noted in 1751, turned “disgusted with Labour, and being educated in Idleness, are rendered unfit to get a Living by Industry.”

During his tours of the colonies as postmaster, Franklin saw schools for black children organized by Thomas Bray, an Anglican minister. This began changing his thinking about the intelligence of African Americans. The black children were “as quick, their Memory as strong, and their Docility in every Respect equal to that of white Children,” he wrote to a member of Bray’s church in 1763. “You will wonder perhaps that I should ever doubt it.” Ten years later Franklin noted that blacks were held back, not for lack of understanding, “but they have not the Advantage of Education.”

An 18th-century antislavery illustration.

Franklin slowly moved to the idea that slavery was an injustice that stained the whole notion of liberty and freedom voiced by America. In 1772 he commented when a British court freed a slave just arrived in London. Britain, he said, congratulated itself on freeing a single slave, while British merchants continued a slave trade “whereby so many hundreds of thousands are dragged into slavery.” A year later he wrote that slavery had “so long disgrac’d our Nation and Religion.”

Pennsylvania Quakers founded the nation’s first abolition society. The state also passed the first laws for the gradual end of slavery. Slave children born after 1780 were freed at age 28. In 1787, Franklin became the president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and the Relief of Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. How could a person “treated as a brute animal” know what to do as an ordinary citizen? He supported efforts to aid freed blacks with jobs and education to help them move into society.

THE SAME year Franklin became president of the Abolition Society, duty called him to a new convention in Philadelphia. The old Articles of Confederation, written during the American Revolution, had run out of steam. Under the Articles, Congress had few powers to govern—it could not coin money, pass taxes, or oversee trade between the states. There was no chief executive or president, no national court system. The states hoarded powers to themselves.

THE SAME year Franklin became president of the Abolition Society, duty called him to a new convention in Philadelphia. The old Articles of Confederation, written during the American Revolution, had run out of steam. Under the Articles, Congress had few powers to govern—it could not coin money, pass taxes, or oversee trade between the states. There was no chief executive or president, no national court system. The states hoarded powers to themselves.

So, should the Articles be preserved so that power remained in the states, or should a new federal government be created, making the United States truly one nation? The delegates decided to scrap the Articles and write a new blueprint of American government.

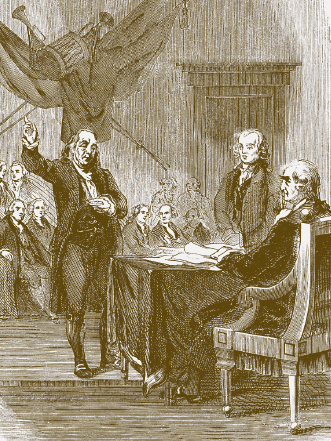

In May 1787, Pennsylvania sent Franklin as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. Ben, age 81, was the oldest delegate. He nominated George Washington for president of the convention. Franklin, with Sally’s help, hosted dinners and casual meetings outside under the shade of his mulberry tree. Throughout the hot, sticky summer, delegates gathered in Franklin’s yard to informally discuss the great matters before them. One man described Franklin as “a short, fat, trunched old man, in a plain Quaker dress, bald pate, and short white locks.” He was “the greatest philosopher of the age … a most extraordinary Man,” who told a story “in a style more engaging than anything I ever heard.”

Poor health kept Franklin away from the convention on some days. Standing to speak racked his poor old body with pain. When he wished to have his views known, he wrote them out and had them read to the convention.

DELEGATES LISTENED politely to many of Franklin’s proposals and then rejected them. These included his idea for a unicameral (or one body) legislature, opening each convention session with a prayer for help and guidance, having an executive council instead of a president, and having officeholders serve without pay.

Franklin did not fear democracy, or rule of the people, as much as most of the men at the convention. He opposed measures requiring a man to own a certain amount of property in order to hold office. He also spoke against property requirements for men to vote. Franklin wrote to a friend in France, “We are making experiments in politics.”

Delegates such as Alexander Hamilton discussed matters under Franklin’s mulberry tree.

Franklin knew that only compromise could give birth to a new constitution. His efforts to bring the other delegates together often left him exhausted. A year later he explained to a friend in France: “Not a move can be made that is not contested; the numerous objections confound the understanding; the wisest must agree to some unreasonable things, that reasonable ones of more consequence may be obtained.”

Franklin contributed to the greatest compromise of the convention, which brought the wary large and small states together. There would be two houses of Congress, the Senate and the House of Representatives. Each state, no matter its size, would have two senators with equal votes, a nod to the smaller states. In the House of Representatives, representation would be based on a state’s population, a nod to the large states. A bill needed approval of both houses to become law.

Slavery would continue in the United States. The convention voted to end the importation of slaves to the United States, but this was not to go into effect until 1808. For the purpose of representation, each slave would be counted as three-fifths of a person.

In September, Franklin urged his fellow delegates to sign the new Constitution of the United States. “I confess,” said Franklin, “that I do not entirely approve this Constitution at present.” But, he told the delegates, he doubted that they could have made a better Constitution. “When you assemble a number of men, to have the advantage of their joint wisdom” you also gained “their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views,” noted Franklin. “It therefore astonishes me, Sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does; and I think it will astonish our enemies,” who waited for America to fail. “Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best.”

As the delegates left the convention, Elizabeth Powell, the wife of Philadelphia’s mayor, caught sight of Franklin.

“Doctor,” she called, “what have we got, a republic or a monarch?”

“A republic, madam” replied Franklin, “if you can keep it.”

FRANKLIN BEGAN work on the third part of his autobiography in 1788, detailing his work to benefit people and his public service up till his arrival in England in 1757. Sometime in the winter of 1789-90, he wrote a fourth section dealing with events of 1758. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin remains in print today, a gem of American literature.

FRANKLIN BEGAN work on the third part of his autobiography in 1788, detailing his work to benefit people and his public service up till his arrival in England in 1757. Sometime in the winter of 1789-90, he wrote a fourth section dealing with events of 1758. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin remains in print today, a gem of American literature.

AS THE delegates stepped forward to sign the Constitution, Franklin mused how he’d often studied the halfsun design on the back of the chair that Washington sat in as president of the convention. He’d not been “able to tell whether it was rising or setting; but now, at length, I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting sun.” And so, Franklin expressed his hopes for the new plan of government.

A close-up of the “rising sun” chair Washington sat in during the Constitutional Convention.

Unlike this 19th-century illustration, the elderly Franklin rarely stood and spoke at the convention.

MATERIALS

Adult supervision required

Spread the newspaper on a table to work on. Add about 2 inches of sand to the foil roasting pan. Dampen the sand with water and stir it around with the paint stirrer. Pat the sand down to be smooth and even.

Using a pencil, trace a rising-sun design into the sand. Make sure the line goes down into the sand about an inch. Make it as fancy or simple as you like. It does not have to match the convention chair.

Cut a piece of chicken wire to fit inside the roasting pan—keep this handy for later. Follow the directions on the plaster packaging to mix the dry plaster with water in the plastic paint bucket. Slowly pour about half of the plaster over the sand, making sure the plaster fills your design in the sand.

To help support your sand casting, place the chicken wire on top of the plaster. Pour the rest of the plaster over the chicken wire and fill the roasting pan.

Cut a piece of the wire coat hanger and bend it like an upside-down block U, as shown. Put the coat hanger U into the plaster along the top edge. This will let you hang your sand casting.

Let the plaster set and dry. When it is completely dried, carefully lift it out of the roasting pan. Brush off the sand or rinse the sand casting with a garden hose; some sand will remain embedded. Your design should show in the plaster. Now—hang your plasterwork up!

Franklin returned to his roots in another way, too. He founded the Franklin Society to help printers needing credit or insurance. And he delighted in helping his grandson Benny set up in the family trade.

Franklin also wrote his will. Over the years he’d helped many of his large family, his siblings, his nieces and nephews, and his children. He left his library of 4,000 books, money, and his papers to Temple. Sally received most of her father’s estate, with the note that Sally’s husband must free his slave. One of Sally’s most valuable gifts was a miniature portrait of King Louis XVI circled with diamonds. Franklin requested that Sally not make vain, expensive, and useless jewelry out of the diamonds. He also left money to both Boston and Philadelphia to aid young craftsmen and mechanics who had served an apprenticeship and wanted to start a business.

Franklin signed (and probably wrote) an address to America about ending slavery and educating and employing freed slaves. In February 1790, Franklin signed a petition urging the new Congress to grant “liberty to those unhappy men who alone in this land of freedom are degraded in perpetual bondage.” The petition challenged the notion that Congress should do nothing about the slave trade until 1808, as written in the Constitution.

The petitions from the Quaker societies unleashed angry debates in Congress. A congressman from South Carolina questioned Franklin’s support for the abolition of slaves, exclaiming, “Even great men have their senile moments.” A congressman from Pennsylvania rushed to Franklin’s defense. Franklin’s views on slavery rose from the “qualities of his soul, as well as those of his mind” and Franklin still could “speak the language of America, and … call us back to our first principles.” But the antislavery petitions died in Congress.

By the spring of 1790, Franklin knew his days were numbered. Gout, kidney stones, lung problems, and a sprained wrist that would not heal plagued his once-energetic body. He spent his time reading. He wrote to a friend that his life had seen him rise from “small and low beginnings to such high rank.” The pricks and pains of old age were a means of weaning him from a world where “he was no longer fit to act the part assigned to him.”

He wrote letters of farewell, including one to the new president, George Washington. Out of all other Americans, perhaps only the president could understand the great fame thrust upon Franklin, for the same thing had happened to Washington.

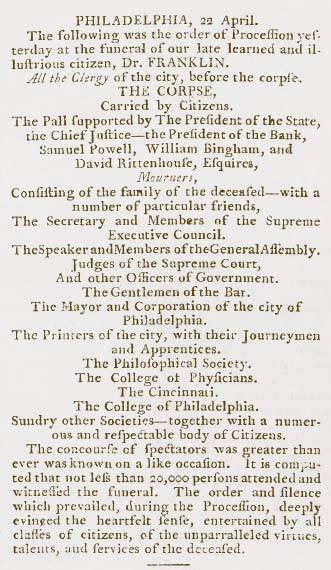

The order of Franklin’s funeral procession from the Gazetteer of the United States.

For my own personal Ease I should have died two Years ago, but tho’ these Years have been spent in excruciating Pain, I am pleas’d that I have liv’d them, since they have brought me to our present Situation. I am now finishing my 84th year, and probably with it my career in this Life; but in whatever state of Existence I am plac’d hereafter, if I retain any Memory of what has pass’d here, I shall with it retain the Esteem, Respect, and Affection with which I have long been, my dear Friend, Yours most sincerely, B. Franklin.

Early in April, Franklin caught a fever. His breathing grew labored and a heavy cough tormented him. Opium relieved some of the pain. Family and friends gathered close at hand—Sally and her husband, his grandchildren, and even Polly Stevenson, who’d moved to Philadelphia with her family. As her father weakened, Sally whispered she wished he’d get better and live many more years. “I don’t,” replied Franklin. At the end an abscess burst in his lung and he could no longer speak. He held Benny’s hand. At 11 P.M. on April 17, 1790, Franklin died with his family at his bedside. He was 84 years old.

Crowds of 20,000 people jammed Philadelphia’s streets to mourn Franklin and witness the funeral procession to Christ Church’s burial grounds. Meanwhile, tributes poured in from France. One Frenchman called Franklin “this mighty genius” who’d spread the rights of man throughout the world, a man “able to conquer both thunderbolts and tyrants.” The French National Assembly declared three days of national mourning for Franklin.

Franklin was the unschooled genius, brilliant and probing, who took Europe by storm. Franklin, who met with kings, held dear his common touch. He was the inventor, the scientist, the curious man who never stopped marveling at the natural world around him. He was a writer, an editor, and a publisher who used his gifted pen to bring change, challenge falsehoods, encourage others, and entertain. Money and power meant nothing to him if they were not used to better people’s lives. There was Franklin the man of compromise, the man who believed a solution could always be found. This Franklin sought solutions as an assemblyman, a commissioner, and a delegate to conventions. Most of all there was Franklin the diplomat, who kept the French alliance—and America’s hopes of independence—alive based solely on his personality, understanding, and skill.

A month before Franklin’s death, Ezra Stiles, a friend, a clergyman, and president of Yale University, asked Franklin for his religious views. Franklin wrote back that he believed in God, the “Creator of the Universe. That he governs it by his Providence. That he ought to be worshipped. That the most acceptable Service we render him is doing good to his other children.” He confessed that while he tried to follow Jesus’ teachings, he wasn’t sure about the divinity of Jesus. He had not studied about Jesus “and think it needless to busy myself with now, when I expect soon an opportunity of knowing the truth with less trouble.”

In a 1785 letter to George Whatley, Franklin, always practical, observed that in nature nothing is wasted, “not even a Drop of Water.” He could not believe that God would “suffer the daily Waste of Millions of Minds ready made that now exist, and put himself to the continual Trouble of making new ones.” Franklin did not see an end in death, but a new beginning. “Thus finding myself to exist in the World,” he wrote to Whatley, “I believe I shall, in some Shape or other, always exist.” He hoped the mistakes of his past life would be corrected in the new.

As a young man in 1728, Franklin had written an epitaph:

The body of

B. Franklin, Printer

(Like the Cover of an Old Book Its Contents torn Out

And Stript of its Lettering and Gilding)

Lies Here, Food for Worms.

But the Work shall not be Lost;

For it will (as he Believ’d) Appear once More

In a New and More Elegant Edition

Revised and Corrected

By the Author.

But at the end, Franklin made only a simple request: a marble slab six feet long and four feet wide, without ornament, to cover his grave. The only inscription—”Benjamin and Deborah Franklin: 1790”—carved across the marble’s face.