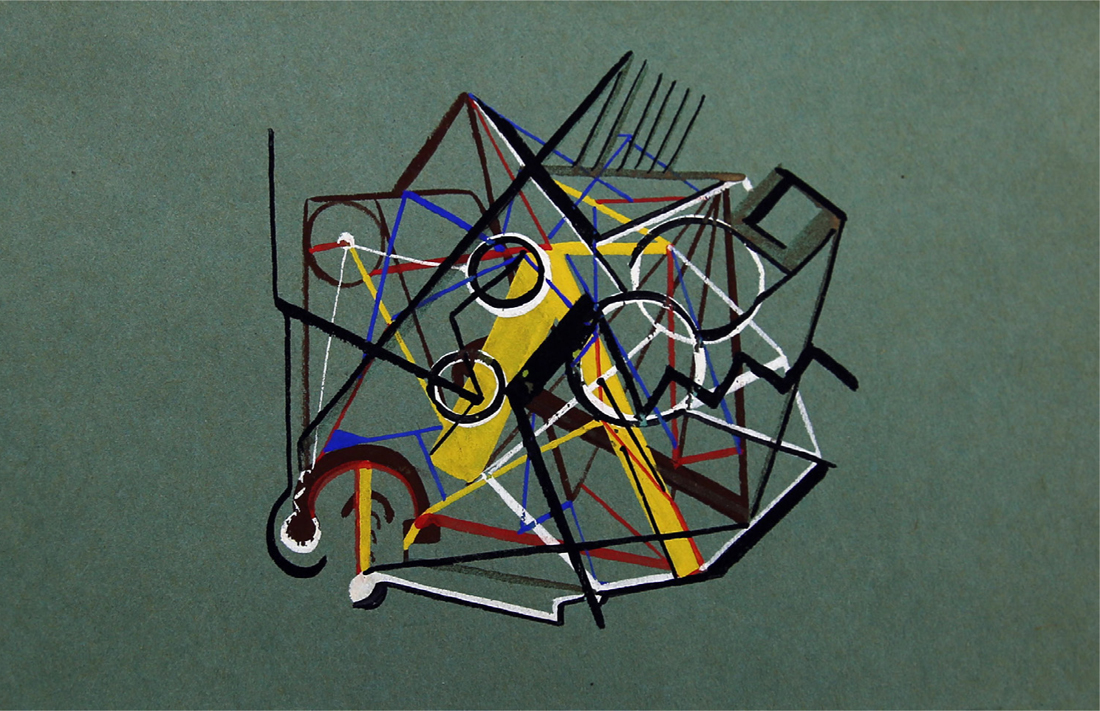

Stage II (Mescaline Drawing with Cones) by Julian Trevelyan, 1936.

As Artaud underwent his spiritual dismemberment in Mexico, peyote religion in the USA faced another high-level challenge to its legitimacy. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics, created in 1930 and expanded after the collapse of alcohol prohibition in 1933, was intent on extending its remit beyond those drugs – opiates and cocaine – controlled by the 1914 Harrison Act. In 1937 the Marijuana Tax Act was passed, effectively banning its sale, and despite the Native American Church’s constitutional status the federal government once more had peyote in its sights. That year the New Mexico senator Dennis Chavéz submitted a bill to the Senate calling for the prohibition of peyote traffic across state lines, which would effectively constitute a ban in all states but Texas.

Peyote retained many sworn enemies, prominent among them Mabel Dodge Luhan (as she was known after marrying Tony). A series of letters from her prefaced a thick file of documents submitted to the Senate, most of which was the same anti-peyote testimony presented at the 1918 House of Representatives hearings. The bulk of the new material related to recent disputes at Taos pueblo between the peyotists and the traditional kiva worshippers, during which Dodge Luhan had urged the elders to arrest those who participated in peyote meetings. In February 1936 fifteen worshippers were charged with public disturbance, convicted and fined $100 each. They appealed to John Collier, now commissioner at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, who supported their case on grounds of freedom of religious practice. Dodge Luhan, whose friendship with Collier had cooled over the years, complained over his head to Harold Ickes, Roosevelt’s secretary of the interior, the man who had recommended Collier’s appointment. ‘Do you really mean that you are defending self-government when you take the side of a few drug addicts against the efforts of the pueblo officers?’ she wrote. ‘Would you stand for hashish, cocaine, or morphine and defend them on the grounds of religious liberty?’1

By this time, however, the assimilationist policies that had driven the suppression of peyote were in retreat. In 1924 Congress had granted full US citizenship to all American Indians, and under Roosevelt and Collier the priorities of the Bureau of Indian Affairs were comprehensively reset. In 1934, after the Indian Reorganization Act, Collier published an executive order entitled ‘Indian Religious Freedom and Indian Culture’ that explicitly rejected assimilation in favour of cultural pluralism. Indians were to be given full access to modern knowledge and education, but they were not to be coerced into Christianity. Collier curtailed missionary activities, prohibited compulsory religious services at boarding schools and retired the Bureau’s hostile pamphlets against peyote. They were replaced with a circular that enshrined the principles he had defended consistently since his early days of activism on behalf of the immigrant cultures of New York: ‘no interference with Indian religious life or ceremonial expression will hereafter be tolerated’.2

Collier rallied a wealth of expert opinion against the bill including the most thorough fieldwork to date, which the young anthropologist Weston La Barre was in the process of writing up for his doctorate at Yale University. La Barre’s study was published in 1938 as The Peyote Cult and over the course of many subsequent editions it became the definitive text on Native American peyote religion. Many of the tribal groups who adopted peyote over the following decades used it as their ritual handbook and bible, and in many respects it was the work that James Mooney had left unwritten at his death. Mooney, La Barre acknowledged, was ‘undoubtedly the expert of the subject’ but in the end had published little about it. His engagement had far exceeded that of his contemporaries, who were ‘in general concerned with preserving complete records of older native cultures, and ignored or paid scant attention to the modern cult of peyote’.3 Under the tutelage of Edward Sapir at Yale, La Barre represented a new generation of anthropologists who aimed to broaden the discipline beyond collecting artefacts and recording traditions, and drew on linguistics and psychoanalysis to elucidate the cultures and mental worlds of their subjects in their own terms.

The Peyote Cult disentangled the persistent linguistic confusions and botanical identifications surrounding the cactus, and used a combination of written records and oral tradition to track the historical diffusion of the ceremony from Mexico to Oklahoma and beyond. La Barre outlined a progression of ritual forms from the Huichol and the Tarahumara through the Mescalero Apache to the Plains ceremony, which he identified as Kiowa–Comanche, ‘historically considered . . . the centre of this diffusion’.4 In Mexico, he proposed, peyote had an essentially ‘tribal’ function, associated with hunting and gathering and with a ritual focus on witchcraft, divination and healing. In the American Plains it had become ‘societal’, a communal bonding drawing on forms of Christian worship, in which individuals were strengthened by their personal visions and confessions in the presence of their peers.5

While participating in ceremonies among the Kiowa in Oklahoma, La Barre noted how they were designed to incorporate and manage the spectrum of peyote’s effects. Its stimulant qualities banished sleep and made all-night sessions possible, and its suppression of hunger made fasting natural. Many of the best-known songs were said to have been elaborated from the auditory hallucinations it induced. A taboo on salt during the ceremony stopped participants from becoming thirsty, and the sweetened ritual breakfast relieved the effects of low blood sugar. The sense of lassitude that characterised the early stages of intoxication was counteracted by the pounding rhythm of drum and rattle; it was after midnight, when these sensations faded and water was passed round, that, as Mooney had observed, ‘the songs of those present are more vigorous’,6 lifting the participants through the hours of darkness.

‘Every student of peyote,’ La Barre wrote, ‘has been met with a sometimes odd mixture of suspiciousness and candor.’ In his experience, a sincere interest was generously rewarded and ‘there is no very great difficulty in a sympathetic white man’s attending a peyote meeting nowadays’.7 The peyotists believed that the cactus had powers that protected it and its adherents against the hostility of the white man, just as in older times it had given advance visions of an enemy’s approach and offered protection in battle. In many ways, La Barre observed, the federal policy of Indian assimilation had strengthened peyote’s power and prestige, making it a touchstone for the lifeways the tribes were struggling to preserve. Education and resettlement policies intended to destroy Indian culture ‘weakened the tradition of the older tribal religions without basically altering typical Plains religious attitudes, and multiplied friendly contacts between members of different tribes’.8 The Native American Church was an authentically Indian response to the conditions the white man had created.

On La Barre’s second visit to Oklahoma in 1936 he was joined by a twenty-one-year-old Harvard student, Richard Evans Schultes; this was to be the latter’s first field trip of a sixty-year career during which he would open up a vast field of psychedelic ethnobotany, from the hallucinogenic mushrooms and morning glory seeds of Mexico to the DMT-containing snuffs and ayahuasca potions of the Amazon. Schultes had initially been inspired to study plant intoxicants by reading Heinrich Klüver’s Mescal in the library of the Harvard Botanical Museum, and its director Oakes Ames had encouraged him to join La Barre and witness its traditional use.9 La Barre and Schultes’s grandly billed ‘Harvard–Yale expedition’ amounted in practice to the pair bumping across the hot and dusty Southern Plains from Philadelphia to Oklahoma in an old Studebaker. Their host and interpreter among the Kiowa was Charlie Apekaum, a game warden and navy veteran whose family had also hosted James Mooney.

Schultes’s later celebrated discoveries would draw on pharmacology to identify the psychoactive agents in healing plants, particularly the combination of DMT and beta-carbolines that give the ayahuasca brew its prodigious visionary power.10 In his report on peyote for the Harvard Botanical Museum he was working with a plant whose chemistry was already established, but he demonstrated the attention to ethnographic and ritual detail that would underlie his future discoveries. He noted that among the many plants involved in the ceremony – cedar and sage incense, mescal beans, fruits, Bull Durham tobacco rolled in corn shucks, sumac leaves, cottonwood smoke sticks – peyote was the only one that was new to Plains tradition.11 It might be a new religion, but the ethnobotany of the ritual revealed deep roots in an extensive complex of traditions and practices. Peyote was now a significant article of commerce: arriving regularly in trailers from southern Texas and Mexico, it sold for $2.50 per thousand buttons.

Schultes joined La Barre for several peyote ceremonies, which he attended in his customary outfit of neatly buttoned shirt, pressed slacks and Harvard tie. But, as they would throughout his long career, the full-blown visionary effects of the cactus failed to materialise for him. ‘I get colours,’ he wrote later, ‘lightninglike flashes, little stars like when you break a glass, sometimes colored smoke going by like clouds. I wish I could see visions. La Barre has tried to explain it to me, but I don’t understand what he is talking about.’12

Both La Barre and Schultes submitted reports for the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, along with a roster of distinguished anthropologists that included Franz Boas and Raymond Harrington, who had convened the disastrous peyote ceremony in Mabel Dodge’s Greenwich Village home twenty years previously and was now curator of archaeology at the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles. Their testimony, published by the Department of the Interior as Documents on Peyote (1937), recommended firmly that Senator Chavéz’s bill should not be enacted. It was voted down by a comfortable margin.

La Barre and Schultes were not alone among their generation in finding peyote more intriguing and significant than the bohemians of the Progressive Era had. Some of the visitors to the Luhan commune at Taos adopted it, such as Jaime de Angulo, an ethnomusicologist who spoke seventeen native American languages. De Angulo was Carl Jung’s guide on his visit to Taos pueblo in 1925, acting as interpreter for Jung’s conversation with the pueblo chief Ochwiay Bianco that Jung would recall at length in his 1963 Memories, Dreams, Reflections: de Angulo was astonished to discover that this was the first time Jung had ever spoken with a non-European. Originally a linguist at the University of California in Berkeley, he had abandoned the academy to immerse himself in shamanism, spiritual exploration and fiction written in the form of native myths, published posthumously as the bestselling Indian Tales (1953). De Angulo never wrote about peyote but brought its lore back with him when he returned to Berkeley where he remained, in the words of the beat poet Gary Snyder, ‘a great culture hero on the West Coast’ until his death in 1950. ‘He never had a regular appointment,’ Snyder recalled in 1970, ‘he was just too wild. Burned a house down one night when drunk, rode about naked on a horse at Big Sur, member of the Native American Church.’13

In Southern California peyote was adopted by the flamboyant rocket scientist and occultist Jack Parsons, a founder of what is now the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena and the resident magus of a commune he formed in the city in 1941 that centred around the Agape Lodge, a branch of Aleister Crowley’s Ordo Templi Orientis. As with Crowley, it is hard to determine whether and how Parsons used peyote in his magickal workings, but it was part of an extensive pharmacopoeia, along with cocaine, marijuana and the amphetamines that Parsons synthesised in his rocket lab, that fuelled the Agape’s orgiastic parties. He placed it in the opening line of the poem he contributed to the first issue of the occult lodge’s journal in 1943: ‘I hight Don Quixote, I live on peyote, / marijuana, morphine and cocaine, / I never knew sadness but only a madness / that burns at the heart and the brain.’14

This conspicuous advertisement succeeded in scandalising the ageing Aleister Crowley himself, who wrote to Jane Wolfe, an old associate from his days in Sicily, ‘What could have been better calculated to revive the ancient stories about drug-traffic and so on?’15

The figure who pointed most clearly to the next generation’s romance with peyote was Frank Waters, who met Tony Luhan on his first visit to Taos pueblo in the summer of 1937 and lived with him and Mabel on the Luhan estate while writing his best known novel, The Man Who Killed the Deer (1942), which he dedicated to them both.16 Waters, who was himself part Indian, fictionalised a real-life incident from the pueblo into a drama of a young man caught between two worlds, returning to his village after education in government boarding school having fallen foul of the law by unwittingly killing a deer out of season. His journey to redemption takes in a peyote ceremony, which is introduced to him and the reader much as Tony presented it to Mabel: ‘This I learned from the Cheyennes and Arapahoes,’ the roadman tells him, ‘and they learned it from the Kiowas . . . but the Kiowas learned it from the tribes of Mexico.’17 During the ceremony the young man receives a vision of the peyote road, which makes him flee into the pines and mountains where he encounters the deer he killed; ‘and he knew that he was an intruding stranger who had not stopped to consider this strange peace, this universal brotherhood between deer and pines and birds’.18 He returns to the ceremony, where he learns that ‘The Road leads to spiritual unity with the Great Father Peyote who in himself contains all.’19

Waters revered Tony Luhan as an ‘older brother’ and ‘ceremonial uncle’20 and this section of the novel bears his imprint, but he was also heavily influenced by Mabel, in particular her reverence for eastern religions and philosophies. She introduced him to the I Ching and the ideas of George Gurdjieff, whom she had met in Paris, after which Waters’ explication of native American beliefs took on a universalist cast in which they merged with Hindu tantra, Jungian mythography, Robert Graves’ The White Goddess (1948) and Walter Evans-Wentz’s edition of the Tibetan Book of the Dead (1927). Waters’ bestselling account of native spirituality, The Book of the Hopi (1963), was regarded by anthropologists as wildly inauthentic but became a founding text for the 1960s counterculture.

By 1940 mescaline experiments were becoming widespread across psychiatry. The field was more systematically oriented around research, with the creation of university departments, professorships and large-scale clinical trials. Research was driven by new sources of funding, particularly the Rockefeller Foundation, which was drawn in by Adolf Meyer, professor at John Hopkins Medical School, and his mission to build links between practising psychiatrists, teaching hospitals and university researchers.

The Rockefeller Foundation extended its programme to Europe, taking as its base the Maudsley Hospital in London, Britain’s leading centre for psychiatric research. In 1937 it funded the Maudsley’s clinical director, Aubrey Lewis, to undertake a fact-finding trip around Europe’s psychiatric institutions and report on the state of scientific knowledge. Lewis interviewed the staff of a clinic in Amsterdam where EEG readings were being taken from monkeys dosed with mescaline, pharmacologists in Kraków who had been trialling its use as a psychiatric medication, and doctors at the Military Academy in Leningrad who had been using it to study hallucinations. In Finland he met a professor working with the eyes of decapitated frogs, to whom he recommended that ‘this was a field in which investigation into the effects of such drugs as mescaline, and also the changes that accompany visual hallucinations might be studied with profit’.21

At this moment a major research project using mescaline was under way at the Maudsley Hospital itself. From 1933 onwards, Jewish psychiatrists removed from posts in Germany by the Nazi regime were sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation to relocate to Britain and several were offered scholarships at the Maudsley. These included Kurt Beringer’s colleague Wilhelm Mayer-Gross, who had become a professor at Heidelberg in 1929, and a fellow psychiatrist from Breslau, Eric Guttman. Guttman teamed up with a Scottish psychiatrist, Walter Maclay, and secured Rockefeller funding for a project testing mescaline on the hospital’s psychiatric patients. Karl Heinrich Slotta, another European émigré and a biochemist at the Maudsley’s neurosurgical unit, provided the mescaline, following the synthesis described by Ernst Späth in his paper of 1919.

Guttman and Maclay were particularly interested in depersonalisation, the state in which a subject’s sense of their body becomes lost and their thoughts seem beyond conscious control. This syndrome was often observed in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and also reported experimentally under mescaline. They considered that the 300mg typically used to generate visions might produce unnecessary distress in mental patients, as might the method of injection, and consequently administered mescaline to their subjects in smaller doses dissolved in water. They noted changes in mood and emotional tone, but even at this mild dose they were highly inconsistent. In Beringer’s subjects euphoria had predominated, but he had been working with healthy, excited and curious medical students. Among mental patients, Guttman and Maclay recorded a few cheerful responses but more who were ‘bewildered’ or ‘depressed and anxious’, and some curious emotional arcs including ‘contented, later depressed’ and ‘depressed, later slightly euphoric’.22 In some cases, they concluded, mescaline seemed to allow patients some insight into their feelings of depersonalisation, with one announcing ‘I have seen that I can be as I used to be before.’23 In most, however, there was no therapeutic consequence and patients were easily able to distinguish the effects of the drug from their habitual sense of depersonalisation.

The parallels between the effects of mescaline and the symptoms of schizophrenia, Guttman and Maclay decided, might be better explored through the medium of art. Studying drawings produced by psychotic patients at the Maudsley and the Royal Bethlem Hospital, the larger mental hospital with which it was associated, they suggested that ‘the character of these hallucinations is very similar to what people describe as their experience during mescalin [sic] intoxication, especially the intensification of colours, the distortion of shapes, the apparent movements and the repetition of lines and patterns’.24 They studied the work of artists-turned-patients such as Louis Wain, who had been a popular illustrator specialising in cartoon cats before being confined to a series of mental hospitals including Bethlem, and whose work included some dazzlingly colourful and abstract compositions.25 They also studied spontaneous drawings – in the recently popularised slang term, ‘doodles’ – and persuaded a newspaper to solicit them from its readers for a competition. This generated some nine thousand entries which filled two sacks, each of which took two men to lift.26

In the course of their researches Guttman and Maclay came to recognise that ‘only a minority of patients have the capacity and drive’ to turn their mental landscapes into art, ‘especially while they are under the fascinating impression of the acute psychotic experience’.27 This suggested to them a new project: mescaline experiments with professional artists whose work under the influence of the drug could be compared with that of psychotic patients. They decided that Surrealist artists might be fruitful collaborators as many of them had an existing interest in Freud and theories of the unconscious, and used techniques such as dream diaries and automatic drawing in their work. They made enquiries via Lionel Penrose, professor of psychology at University College London, whose brother Roland was a member of the small and tightly knit group of British Surrealists. They succeeded in recruiting several participants including Julian Trevelyan, who had begun his career in Paris working alongside Max Ernst, Joan Miró and Picasso and was one of the organisers of London’s International Surrealist Exhibition of 1936, and Basil Beaumont, who had also studied in Paris at the modernist Académie de la Grande Chaumière and subsequently established the Society for Creative Psychology in London.28

The experiences of the artists turned out to be as unpredictable as those of the patients. Trevelyan recalled being driven to the hospital in the morning and injected with mescaline crystals in solution at around 10 o’clock; after an hour of slight nausea, ‘suddenly the fireworks started, with their magical transfiguration of everything I looked at’.29 His hand shook as he attempted to draw what he was seeing, ‘yet while it lasted I could not put a line wrong; the line was no longer on the surface of the paper but quivering in space like a wire. Perspectives and recessions dripped off my pencil.’ When he shut his eyes ‘a world of cosmic imagery, a sort of mechanical ballet, became visible’. After a couple of hours he was taken to lunch in the hospital canteen, where ‘I remember sitting at a table amongst white-coated doctors, with a plate of spaghetti and cauliflower in front of me, whose intricate forms fascinated me beyond belief.’

1. A cluster of the mescaline-containing San Pedro cactus growing at the temple site of Chavín de Huantar in the Peruvian Andes, where its ancient use is attested by a 3,000-year-old bas-relief.

2. San Pedro was commonly depicted in the pre-Hispanic art of Peru’s coastal cultures, such as this stirrup-spout vessel, on which the cactus stems are entwined with jaguar heads.

3. The first botanical drawing of the peyote cactus appeared in Curtis’ Botanical Magazine in 1847. At this point its mind-altering properties were unknown to western science.

4. In Le peyotl (1926), the French pharmacist Alexandre Rouhier introduced European readers to peyote’s botanical history and its ancient use in divination and healing. He cultivated the plant on the Côte d’Azur and marketed an extract, Panpeyotl, for ‘psychological experimenters wishing to study the mental phenomena produced by powerful doses’.

5. A Huichol mara’akame (shaman) hunts peyote in the sacred landscape of Wirikuta, in the high desert of northern Mexico.

6. Peyote is a common motif in contemporary Huichol art, in which dazzling coloured yarn is pressed onto a wooden board with beeswax. This work by Alejandro Lopez Torres uses the form of the cactus to represent the five pillars that support the sky.

7 & 8. James Mooney (left), ethnologist with the Smithsonian Institution, and Quanah Parker (below), chief of the Comanches, were both powerful advocates for the peyote religion of the Plains tribes. In 1893 Quanah supplied Mooney with 50 pounds of dried peyote buttons, which Mooney brought back from Oklahoma to Washington. They were used in the first scientific trials, including self-experiments by the neurologist Weir Mitchell and the philosopher William James.

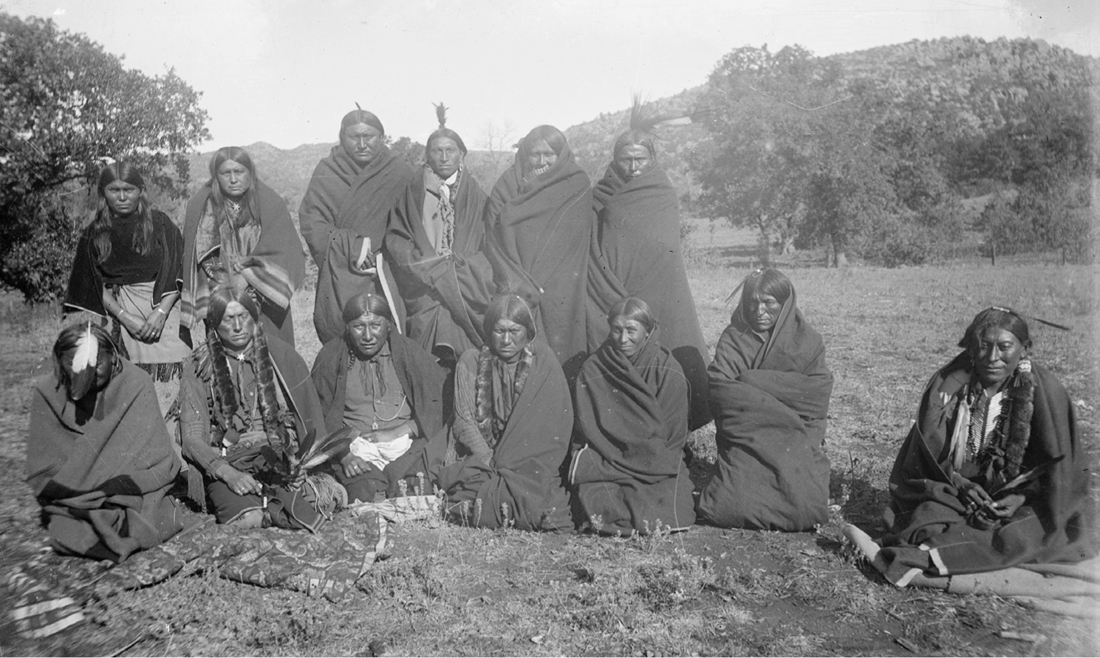

9. This photograph was taken by James Mooney in November 1893, the morning after an all-night peyote meeting with Quanah Parker (second from left, front row) and his Comanche band in the Wichita Mountains, Oklahoma.

10. Peyote Medicine Man (1973), by the Kiowa artist James Auchiah, depicts the elements of the Plains peyote ceremony: the tipi, the rattle and drum that accompany the songs, the sacred eagle feathers, the curved altar of mounded earth and the peyote occupying its central place of power.

11. The Polish artist Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz experimented with both peyote and pharmaceutical mescaline, writing about them in his essay-memoir Narcotics (1932) and painting under their influence. He regarded these works as collaborations with the drug: this portrait from 1929 includes ‘Mesk’ (mescaline) and ‘C’ (alcohol) in the signature.

12 & 13. In 1936 two psychiatrists at London’s Maudsley Hospital enlisted British Surrealist artists to paint under the influence of mescaline. The work above is anonymous; below is the painting by Basil Beaumont, who left a description of his nightmarish experience in which time ‘went very wrong’, his supervising psychiatrist took on the appearance of ‘a most diabolical goat’ and he ended up spending the night in a mental hospital ward.

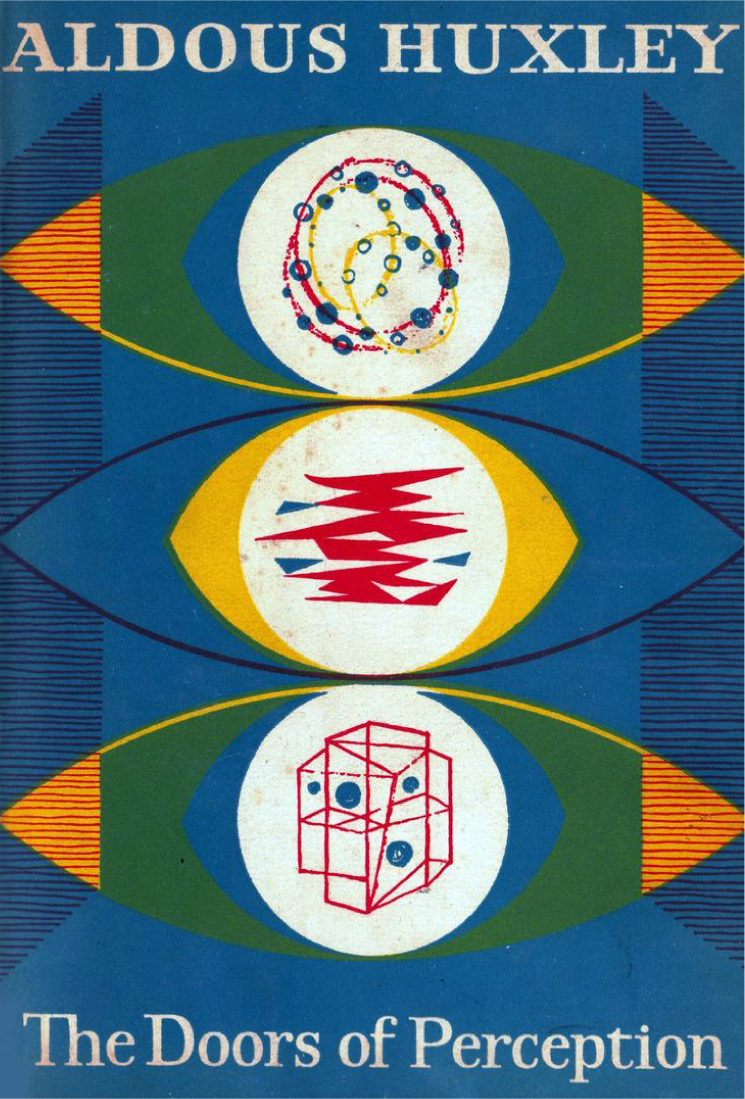

14. The publication of Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception in 1954 made mescaline world famous. John Woodcock’s cover design for the British edition reflected Huxley’s marriage of science and mysticism and anticipated the psychedelic style of the decade to come.

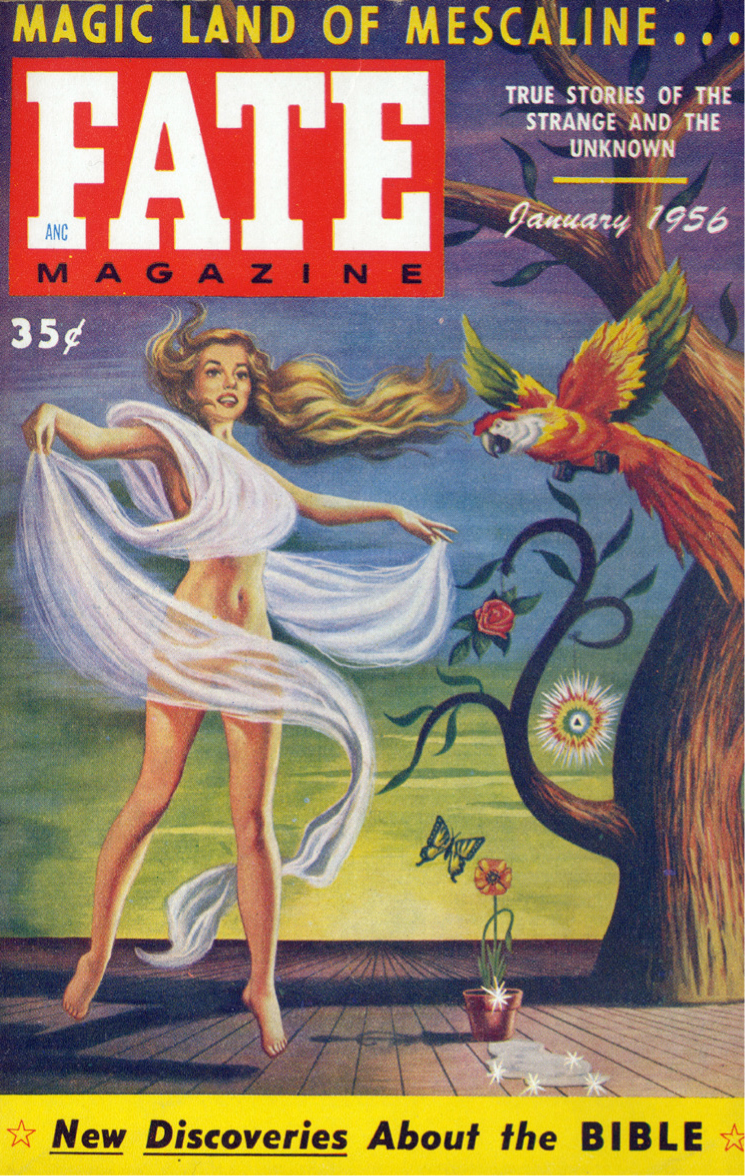

15. After Huxley, mescaline became a subject of fascination in popular culture, as seen in this 1956 cover story of Fate magazine, which concluded: ‘science is probing into a fabulous new universe of the mind’.

Trevelyan took mescaline on two subsequent occasions and felt, much as Havelock Ellis had, that its primary effect was ‘the hyper-awareness of the beauty of things’. This heightened sensation endured long after the experiment was over, and instilled in him the truth of Constable’s statement that ‘I never saw an ugly thing in my life’.30 ‘Under Mescalin [sic],’ he wrote, ‘I have fallen in love with a sausage roll . . . I have also looked at pictures by Picasso, Van Gogh, Michelangelo, and others, and have rejected them all as “ready-mades”.’ Some of his productions under the influence are labelled ‘Stage 1’ and others ‘Stage 2’, denoting those produced under the influence and after it had worn off: they are surprisingly similar to one another, and not very different from the geometrical clusters of cones and branches that he had produced on occasion before the experiment. He felt ‘they have remained valid, though I know they are not great works of art’, but ‘only the traveller’s sketches from that surprising region of the mind, from which, without Mescalin, I am forever debarred’.31

Basil Beaumont’s experiment began identically with an injection at 10 o’clock but unfolded quite differently. He felt sick, cold and shivery, afflicted with twitching feet and hands and a feeling of paralysis around the injection site. The trees outside the window ‘became waving, serpentine forms like octopuses’,32 and the walls of the room filled with Aztec designs that put him in mind of human sacrifices. Colour formations unfurled, ‘never reaching a climax; pure colour and sound without orchestration, rest or pause – almost unendurable’. ‘Excruciating pain and fear’ blended with ‘exquisite beauty of form and sound’ in ways that he found impossible to communicate: ‘it was too painful and too wonderful’. Time ‘went very wrong’, expanding and contracting; doctors came in and out, asking him questions. Dr Guttman appeared as ‘a most diabolical goat’, though Beaumont was keenly aware that he remained his only connection to sanity.

At Guttman’s insistence, over Beaumont’s objections, they went for lunch. The walk to the canteen was interminably long, through undulating corridors; Beaumont was seated at a table with Guttman and another experimental subject who kept asking, ‘And is this the state actually known as the psychosis, doctor?’ Other doctors arrived; Beaumont recalled that ‘I thought they were making fun of me, then I thought they were mental patients; finally I decided that they had all been injected with the drug.’ Tea in the clubroom, amid conversation about ‘Fascism, Communism and the Jews’, was an excruciating ordeal that Beaumont decided must be some sort of psychological test. Then somehow it was dusk and Guttman led him into the garden, where ‘suddenly I believed that I was to be offered as a sacrifice’. The doctor hoped that fresh air would bring him round, but he was constantly being drawn ‘miles and miles away into the world of illusions’.

As night fell a taxi was summoned and Beaumont, in the company of another experimental subject, was driven to the home of his psychoanalyst, Dr Karin Stephen, in Bloomsbury. When he arrived there he was convinced it was a simulacrum or stage set (he later discovered that it had, in fact, been recently redecorated). After he told Stephen that he believed her to be an impostor, ‘it was decided that I should be better spending the night in the M. [Maudsley] hospital’. When he arrived back he was led to a general ward of mental patients; he ‘could not take my gaze off the locks on the doors’ and ‘could not believe that Dr. G. was going to leave me there’. After a terrifying night of hallucinations, he was given breakfast and conversed with a nurse who ‘gave me the impression I should be there for at least two weeks’.33 Finally Guttman arrived, discussed the experiment and made notes, and Beaumont was released.

Karin Stephen was appalled by Guttman’s conduct. He had inflicted on his subject, she wrote to him, ‘an experience so hideous that no human being ought to undergo it without the very gravest necessity’.34 He had at different points during the ordeal had murderous delusions and suicidal thoughts. Guttman assured her that ‘I did not start giving Mescalin light heartedly or without adequate preliminary investigation,’35 although he confessed he had been unaware that Beaumont was undergoing psychoanalysis. He had ‘myself taken it in larger doses than I gave to Mr. Beaumont’, and had taken precautions against ‘suicidal or homicidal ideas which come up to the surface of consciousness during such an intoxication just as they do during psychotherapy’. He had subsequently received a note from Beaumont which described a much more rewarding experience. Generally, Guttman assured her, ‘the anxiety is forgotten and there remains the recollection of a most interesting and fascinating experiment’.36

Beaumont’s short note to Guttman made no mention of his trauma, apart from thanking him ‘for all the trouble you took with me that night. I must have been very tiresome I am sure.’ He went on to write that ‘My appreciation of beauty, particularly flowers, is still enhanced greatly. My painting is becoming more brilliant in colour I think.’37 Trevelyan was probably referring to Beaumont when he wrote later, ‘There were other members of our little surrealist group who lent themselves to Mescalin; some had interesting hallucinations, but others who suffered from secret griefs were reduced to a state of acute hysteria; for Mescalin transports only those who are carefree travellers.’38

Guttman and Maclay’s experiments inspired another clinical study at Warlingham Park Mental Hospital in nearby Croydon, where an assistant medical officer, G. Tayleur Stockings, had been administering the sedative sodium amytal to patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, after which he found them more able to give coherent accounts of their mental states. Reading Guttman and Maclay’s work suggested to Stockings that mescaline might achieve similar results. He began by acquiring some from the London office of the pharmacy giant Burroughs Wellcome and administered it to ‘a group of normal adults of ages from twenty to thirty years’ and to himself. He noted that the drug produced some of the same physical symptoms, such as dry lips and tongue, flushed complexion and unnaturally bright eyes, as ‘an acute toxic confusional psychosis or acute schizophrenic episode’.39 He enumerated the similarities – hallucinations, delusions, disturbances of the intellect and the will – as many had before him, and much as Jacques-Joseph Moreau had with hashish a century earlier. He detected a ‘close similarity of the art-forms and symbolism of the ancient Mexicans and Central Americans, who use mescaline freely in their religious rites, to the symbolic drawings of schizophrenic patients’.40

From these findings, however, he reached a novel conclusion: that the similarities might point to a shared chemical cause, ‘probably a toxic amine with chemical and pharmacological properties similar to those of mescaline, and having a selective action on the various higher centres of the brain’.41 Mescaline might achieve its hallucinatory effects, in other words, because of its chemical similarity to an organically occurring toxin that causes psychosis. This was the theory that launched psychiatry on the path that would, on that bright May morning in 1953, introduce mescaline to Aldous Huxley.

During the 1930s mescaline had occasionally been considered, along with more or less every other psychoactive drug, as a potential ‘truth serum’,42 with the potential to elicit private and sensitive information from subjects under its influence. Across Europe and the US, experiments along these lines gained pace with the arrival of the Second World War and the loosening of peacetime codes of patient consent and safety. Though they came to focus on scopolamine, barbiturates, methedrine and the sodium compounds pentothal and amytal, mescaline was the first drug trialled in Washington, DC, in 1942 by a ‘Truth Drug Committee’ established by the recently formed Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA, under the supervision of Dr Winfred Overhoser, director of the federally operated St Elizabeth’s Mental Hospital. It was quickly rejected on the grounds that it made subjects too nauseous to trust their interrogators, and the committee proceeded to try marijuana instead.43

By this time there were suspicions that the Germans were using mescaline as a truth serum. A communication intercepted by British code-breakers at Bletchley Park indicated that injecting parachutists with scopolamine had shown some success and ‘therefore experiments with mescaline are to be undertaken’.44 But the full atrocity of such experiments only became clear after the war, when they were described to the US Naval Technical Mission in Europe by medical officers at Auschwitz and Dachau.45 The appalling ‘aviation tests’ in Block 5 at Dachau, in which captive subjects were crushed and frozen to death, also included attempts to ‘eliminate the will of the person examined’ with drugs including mescaline, ‘a Mexican drug that has been reputed to dissolve repressions and encourage talkativeness’.46 Thirty subjects, mostly Jewish, Romani or Russian, were given mescaline in coffee. It turned out to be a disappointing truth serum. Responses were unpredictable: some prisoners became ‘furious, in other cases very gay or melancholy’.47 The nausea was distracting, as were the hallucinations. The only consistency was in the prisoners’ attitude to their captors, where ‘sentiments of hatred and revenge were exposed in every case’.48

The tests were run by Dr Kurt Plötner, a lecturer at the University of Leipzig, who after the war was promptly recruited by the CIA and in 1950 began work with them on Project BLUEBIRD, a secret programme of research into behaviour modification and mind control that would later develop into the notorious MK-ULTRA project. Other German doctors, however, were exploring mescaline’s potential for therapy. In 1938 the Hamburg psychiatrist Walter Frederking had begun to administer it in mild doses to produce ‘drug-induced dream-like states’49 in which the patient’s childhood memories and symbolic associations could be explored more rapidly and deeply than by talk therapy alone. Mescaline made patients easy to direct in conversation, and was especially conducive to approaching delicate subjects such as marital relations or impotence. At larger doses of 300–500mg his patients ‘found the mescaline effect to be overpowering, deeply moving, elemental, spacious’.50 There was a risk of abrupt and intense mood changes, but also the potential for profound insights that could radically shorten the course of treatment.

After the war Frederking became acquainted with the author Ernst Jünger, who had moved in 1939 to the village of Kirchhorst, between Hanover and Hamburg, where he was attempting to recapture his pre-war life of ‘meditations, prolonged reading, walks on the moors and the wooded plains, little get-togethers with a small circle of intimate friends’,51 while sitting out the four years during which he was banned from publishing by the occupying British forces for refusing to submit to their ‘Denazification’ process. Jünger had spent much of his life experimenting with drugs, though he would not write about them directly until the late 1960s. Before the First World War he had been initiated into the rites of Bacchus – or, as he preferred, Gambrinus, descendent of ‘the Æsir, the eight Nordic gods, those prodigious drinkers of mead’52 – in youthful camping trips to the mountains as part of the back-to-nature Wandervögel movement. The Great War had been the making of him both as a soldier and an author with his powerful memoir of the Western Front, Storm of Steel (1920). ‘After the First World War,’ he later wrote, ‘something supervened . . . a sense of claustrophobia, or suffocation.’53 Having tested himself to the limit and stared death in the face, he found the ignoble compromises of Weimar democracy and the regimented utopias of totalitarianism equally unappealing. Drugs became for him the continuation of war by other means. In hospital in 1918 after narrowly surviving an artillery attack he experimented extensively with ether, and in 1920s Berlin with cocaine. Subsequently he moved on to opium and hashish. He knew of mescaline at that time but never encountered it, and consequently when he met Frederking the possibility ‘excited my imagination with the prospect of all kinds of fabulous adventures’.54

Like Walter Benjamin, Jünger was in thrall to the drug writings of Baudelaire, but he read them very differently. Where Benjamin saw the potential for political resistance in expanded consciousness, Jünger saw a weapon of the individual against society. He had by this point elabor-ated an expansive cultural history around drugs and the pursuit of Rausch.55 In his scheme the New World had a different historical trajectory from the Old. In the traditional cultures of the Americas, Rausch had never been overthrown, and ecstatic intoxication had remained at its cultural core. He resisted the term ‘psychedelic’ when it emerged, preferring his own coinage ‘Mexican drugs’ to descibe mescaline, LSD and psilocybin, reflecting what he regarded as their botanical and cultural homeland.

Jünger traced the culture of Rausch in western civilisation back to the mystery religions of classical antiquity, after which the cult of intoxication had been overthrown by Christianity. It had been rediscovered in the nineteenth century by the likes of Baudelaire and Thomas De Quincey and ‘around their trunk a whole new literature grew like a vine’. But the Romantics and the fin-de-siècle Decadents conceived themselves as outcasts and their ecstatic pursuit of Rausch was rejected by the masses as ‘a theft from society’.56 Jünger, raised on Nietzschean individualism and, as a friend of Martin Heidegger, on phenomenology (‘philosophy in the virgin jungle’, as he called it),57 was the avatar of a new culture that would embrace it wholeheartedly. When he met Walter Frederking he was working on his futuristic novel Heliopolis (1949), which featured a drugs researcher who ‘captured dreams, just as others seem to pursue butterflies with nets’ and ‘went on voyages of discovery in the universe of his brain’.58 Jünger would later coin the enduring term ‘psychonaut’ to describe such inner explorers.

Jünger hosted Frederking at his cottage on several occasions, and in January 1950 Frederking arranged for them to take mescaline together at a spacious private house on the edge of Stuttgart. They took the initial dose at about three in the afternoon, and another an hour later. After some mild nausea Jünger was ‘immersed in visions, meditations, visual and auditory perceptions’ until early evening. When ‘the flow of images was no longer sufficient’, he insisted on a third, stronger dose.59 Frederking performed a Chinese dance wearing ‘a lampshade on his head, as if it was a conical straw hat worn by the peasants of the rice paddies’. Jünger felt that Frederking’s abilities ‘embraced much more than psychologists could offer, in general’: he had ‘the artistic substance’, without which knowledge ‘turns insipid, as if it lacked salt’.60 Under mescaline, he pronounced, ‘the therapist enters the domains of the priest . . . only they can lead us by the hand, far away, towards the nameless and even a little further’.61

Jünger took mescaline several more times but ‘did not succeed in re-experiencing the intensity of the first trip’ with Frederking in Stuttgart. During a solitary experiment at home looking at a snow-covered field, with a dog howling in the distance, ‘the sinister predominated’. He gazed at his bookshelf and sensed acutely the folly of believing that authorship was a form of immortality; rather, it is ‘a minor loan limited in time’. This was a painful realisation and ‘it is good that our perception filters it’. But for the modern individual ‘only thus does the mask fall and we recognise that the sinister is in reality our home – only by passing through estrangement can we recover the confidence in what is normal’.62

By this time Jünger was in correspondence with an avid fan named Albert Hofmann, a research chemist working for Sandoz Pharmaceuticals in Basel, Switzerland, who had recently developed the chemical that would within a few years eclipse mescaline. ‘My first correspondence with Ernst Jünger,’ Hofmann recalled, ‘had nothing to do with drugs; rather I once wrote to him on his birthday, simply as a grateful reader.’63 The correspondence quickly turned to LSD, which Hofmann had first synthesised at the Sandoz laboratory in 1938 while testing derivatives of ergotamine, an alkaloid derived from the ergot fungus, in the search for a vasoconstrictor to treat haemorrhages. By chemical cleavage he produced lysergic acid, a rather unstable compound that he combined with a sequence of different amines. The twenty-fifth in this series, lysergic acid diethylamide, was labelled LSD-25. In 1943 – on the strength, according to his later memoir, of ‘a peculiar presentiment’ – he resynthesised it, after which he felt a slight dizziness and ‘dream-like state’.64 At 4.20 p.m. on 19 April he took ‘the smallest quantity that could be expected to produce some effect’,65 a quarter of a milligram, and set off home on his bicycle. That afternoon and evening, during which (by his later account) his world dissolved into a galaxy of kaleidoscopic spirals and fountains, stands together with Aldous Huxley’s bright May morning as the origin myth of the psychedelic era.

Hofmann recognised that the action of LSD on the mind ‘was not new to science. It largely matched the commonly held view of mescaline.’66 He recalled the work of Beringer and Klüver a generation previously, and the fact that mescaline had demonstrated no medical applications. The significant difference between them was LSD’s extraordinary potency: what he had expected to be a barely perceptible threshold dose had turned out to be a full-blown psychedelic ordeal. ‘The active dose of mescaline, 0.2 to 0.5g,’ he realised, ‘is comparable to 0.00002 to 0.0001g of LSD; in other words, LSD is some 5000 to 10,000 times more active than mescaline!’67 By 1943 Sandoz were breeding new strains of barley and ergot to extract ergotamine in bulk, and they moved swiftly into production of LSD under the brand name Delysid. Unsure of the appropriate dosage or medical applications, they made it available to research institutes and psychiatrists as an experimental drug, offering it free in return for clinical feedback.

In February 1951 Hofmann had the ‘great adventure’ of an LSD experiment with Jünger, who became his mentor in the programme of inner exploration that had unexpectedly been thrust upon him. It was the first LSD trip ever undertaken outside the context of clinical research and Hofmann set the stage with aesthetic stimuli: red-violet roses, and Mozart’s concerto for flute and harp. ‘In mutual astonishment’ the pair contemplated ‘the haze of smoke that ascended with the ease of thought from a Japanese incense-stick’, and as the effects became more powerful they fell silent and closed their eyes. Jünger ‘enjoyed the colourful phantasmagoria of oriental images; I was on a trip among Berber tribes in north Africa, saw coloured caravans and lush oases’.68 But the dose that was sufficient for Hofmann was far too cautious for Jünger, who concluded that ‘compared with the tiger mescaline, your LSD is, after all, only a pussycat’.69

Jünger reported on his experience to Frederking, who sourced some LSD from Hofmann and introduced it into his psychiatric practice. As one of the few clinicians who had been using mescaline for years, he was able to make a closer comparison than most of the early researchers. Putting aside the huge difference in potency, he concluded that mescaline was the more ‘overpowering’ of the two, with a deeper psychic reach, and should be preferred to LSD ‘in cases where the strongest possible emotional upheaval is desired’.70 LSD, by contrast, was easier to dose with precision and more ‘circumscribed’ in its effects, concerned mostly with ‘pleasurable and unpleasant sensations’. In this respect its effect was comparable to manic-depressive mood disorders, whereas mescaline’s was often ‘interspersed with tensions almost schizophrenic in nature’.71 As his practice continued Frederking found himself using LSD more frequently than mescaline, since its interventions could be more precisely targeted and it could be ‘used more often without the risk of harmful effects’.72

The discovery of LSD came at a transformative moment for psychiatry. Its first International Congress, held in Paris in September 1950, demonstrated that biological and chemical approaches had attained a critical mass. Delegates were presented with new research on metabolic systems in the brain, findings from chromosome studies, conclusions drawn from EEG data and thyroid activity measured by radioactive isotopes, much of it developed over the previous decade with support from the Rockefeller Foundation and similar funding bodies. Drawn by these advances in brain science, more medical graduates were choosing psychiatry than ever before: in 1951 the American Psychiatric Association had 8,500 members, up from 3,000 in 1940. Their ambitions fuelled a trend away from practice in mental hospitals and towards research programmes that were being driven and shaped by pharmaceutical companies such as Sandoz as much as by the universities. Psychiatry was developing a hard scientific core, with psychopharmacy at its centre.

The first major pharmaceutical breakthrough of the new era was every bit as unexpected as Albert Hofmann’s discovery of LSD. The French neurosurgeon Henri Laborit was searching for a compound to potentiate anaesthesia and minimise surgical shock when in 1950 he synthesised an antihistamine derivative, chlorpromazine, that had unusual sedative qualities. In informal trials with patients suffering from psychotic disorders at the Sainte-Anne Hospital in Paris, he found they became not groggy but calm and indifferent to their mental disturbances. In some cases the chronically withdrawn and catatonic were miraculously restored to full consciousness. Chlorpromazine was licensed in the USA in 1954 under the brand name Thorazine by Smith, Kline & French, who were expanding rapidly thanks to their successful antidepressant Dexamyl, a combination barbiturate and amphetamine. Thorazine was orginally marketed as an anti-emetic but as news of its remarkable calming effects on schizophrenic patients spread it was prescribed by psychiatrists and became a mainstay of mental hospital regimes. The optimism with which it was adopted was such that it was given to around 50 million people before it became clear that its side effects included tardive dyskinesia, an incurable neurological condition.

The near-simultaneous arrival of chlorpromazine and LSD transformed research into psychotic disorders, in particular schizophrenia. If mescaline and LSD could instigate a model psychosis, chlorpromazine could now switch it off. The classification of mental disorders proposed by Emil Kraepelin fifty years previously had always lacked an essential component: it was a list of diseases without a corresponding list of cures. Now the combination of ‘psychotomimetics’, as mescaline and LSD were known in the new psychiatry, and ‘antipsychotics’ – chlorpromazine and its successors such as haloperidol – promised to unlock the mysteries of mental illness. If psychoses responded to chemical stimuli, they must have a biochemical basis and potentially a pharmaceutical cure.

Mescaline’s new role as psychotomimetic brought it into the mainstream of psychiatric research for the first time, but it pushed its subjective effects to the margins. The experience it produced was not under investigation; researchers rarely took it themselves, administering it instead to lab rats or day-old chicks. Dozens of studies attempted to establish whether its effects were associated with changes in metabolism, such as endocrine activity; whether its metabolites could be detected in urine; whether it produced electrical or biochemical changes in the brain; how soon after birth its functions were detectable. Some psychiatrists, such as Herbert Denber at the Manhattan State Hospital in New York, experimented with administering mescaline in combination with chlorpromazine to mental patients with diagnoses of schizophrenia. Denber recorded some of his patients’ responses, which included ‘like an emotional brain wash’ and ‘a horror, a torture chamber’.73 He noted that ‘aggressivity and hostility’ was often directed at figures of authority, ‘usually the physician’.74

In psychotomimetic terms, LSD’s extraordinary potency made it a precision tool. Mescaline, in common with other psychoactive drugs such as cannabis and opium, had been regarded by early psychiatrists such as Emil Kraepelin and Karl Jaspers as a poison that achieved its mind-altering effects by flooding or overwhelming normal brain functions. The effect of LSD at tiny microgram doses, by contrast, suggested that it was acting on a very specific chemical trigger mechanism, and it quickly rose to become the research chemical of choice. But mescaline had one quality that LSD lacked, and which generated the boldest of the early biological hypotheses. It was the brainchild of two British psychiatrists, Humphry Osmond, a senior psychiatric resident at St George’s Hospital in London, and John Smythies, a young researcher with multidisciplinary interests that spanned neuroanatomy, philosophy and psychical research, who began a residency at St George’s in 1951.

Within two weeks of his arrival Smythies, who had been drawn to the mind sciences after a spontaneous mystical experience while studying medicine at Cambridge, began researching mescaline and its hallucinations. During his survey of the literature he came across the illustration in Alexandre Rouhier’s Le peyotl of its molecular structure, which Rouhier presented alongside those of peyote’s other alkaloids.75 Smythies was struck by its simplicity and at the same time by its resemblance to adrenaline, the hormone produced in the adrenal glands that was known to modulate the activity of the sympathetic nervous system. Adrenaline was also a phenethylamine, and had been synthesised in the laboratory as far back as 1904. Along with Osmond, who shared his interest in the mental phenomena of schizophrenia, Smythies ordered a sample of mescaline from the London medical suppliers Lights Chemical.

Osmond was the guinea pig for an experience that he would within a few years christen ‘psychedelic’ but at this point conceived as psychotomimetic. He took 400mg of mescaline in Smythies’ apartment just off Wimpole Street, in the centre of London’s medical district, accompanied by Smythies, his wife Vanna, who was a nurse, and another friend with a tape recorder. The drug announced itself to Osmond with a building sense of unease and tension, summoning vivid memories of ‘dangerous times in the past’,76 particularly London during the Blitz, which Osmond had endured while at Guy’s Hospital medical school. The tape recorder glowed with menacing purples and reds, and the room shivered: ‘I knew that behind those perilously unsolid walls something was waiting to burst through.’77 Osmond’s companions took him outside for some fresh air but the city’s streets seemed even more threatening, with passers-by covered in warts and a child with a pig-like face staring through a window. They quickly returned. The apparently imagined fears of schizophrenics, Osmond realised, were acutely real. ‘We should listen seriously to mad people,’ he wrote afterwards; they experience ‘voyages of the human soul that make the wanderings of Odysseus seem no more than a Sunday’s outing’.78

Osmond’s experience, combined with Smythies’ observations about the mescaline molecule, prompted them to a hypothesis that they rushed into print in the British Journal of Psychiatry. The ‘adreno-sympathetic system’, they argued, was ‘one of the most constant features’ of schizophrenia’s signature symptoms of mental excitement and disturbances. Might it therefore be a ‘synthetic illness’, produced by a toxic substance in the brain?79 This line of reasoning was supported by the similarity between mescaline’s effects and the symptoms of schizophrenia, and also by ‘the striking implications of the relationship between the bizarre Mexican cactus drug and the common hormone’ adrenaline, which had ‘so far as we know, never been recorded before’.80 They summarised the similarities between mescaline and psychosis in a tabulated checklist that included sensory disorders, motor disorders, thought disorders, delusions and depersonalisation.81

The list was similar to the one that Wilhelm Mayer-Gross had compiled back in the 1920s; but Mayer-Gross, now at Crichton Royal Hospital in Scotland, had recently published a new paper on the subject in the British Medical Journal that highlighted some significant differences. Subjectively, it appeared, the two were quite easy to distinguish. ‘If mescaline was given to a chronic schizophrenic,’ Mayer-Gross had found, ‘the patient distinguished the new phenomena and remarked on their appearance, usually laying blame for them on the same persecutors who had molested him before.’82 Osmond and Smythies responded that ‘the remarkable thing is that these these acute reactions have so much in common’, and that ‘mescaline reproduces every single major symptom of schizophrenia, although not always to the same degree’. The difference, in their view, was between a brief, acute intoxication with the drug as a known cause and a ‘psychosis of indefinite duration in an unprepared subject’.83 The symptoms of schizophrenia were capacious enough to find support for their hypothesis even in Mayer-Gross’s report that Christian missionaries among the Native Americans ‘insist that its regular intake leads to increasing laziness and impairment of will power’.84 ‘Surely,’ they argued, ‘a lay person might describe a chronic schizophrenic in such a phrase?’85

On this evidence Osmond and Smythies proposed their biological theory. It had recently been suggested that adrenaline was produced in the brain from noradrenalin by transmethylation, a breakdown process whereby a methyl group is transferred from one compound to another. Similar processes had been well studied in plants. Could transmethylation of adrenaline in the brain produce a substance similar to mescaline? The pathological process might be triggered by stress overworking the adrenal glands; there might also be a hereditary disposition to it. The presence of this substance in the brain would create distortion of perception and thoughts: in other words, the symptoms of schizophrenia. ‘We therefore suggest,’ they concluded, ‘that schizophrenia is due to a specific disorder of the adrenals in which a failure of metabolism occurs and a mescaline-like compound or compounds are produced, which for convenience we shall refer to as “M-substance”.’86 Once triggered, the physical symptoms of schizophrenia would be compounded by social factors. Faced with an unfamiliar and threatening world of distorted perceptions, as Osmond had been in his mescaline experiment, the subject’s ‘painfully learned patterns of behaviour suddenly become useless and he is left isolated and enmeshed in his own fantasies and the phantasmagoria produced by M-substance’.87

Osmond was unable to find funding in Britain to pursue their research; he recalled that one of the directors of the Maudsley Hospital ‘literally laughed at him’.88 Smythies suspected that the consultants at St George’s, committed to Freudian orthodoxies, considered newfangled biochemical theories of the mind to be ‘rather bad form’.89 Instead, Osmond answered an advertisement in the Lancet for a deputy director of Saskatchewan Mental Hospital, a remote institution deep in the Canadian prairie but one administered by a social democratic government committed to progressive mental health approaches, where research could be conducted with minimal bureaucratic interference.

On arrival at the hospital, a cluster of four-storey blocks among flat grasslands that receded to the horizon, Osmond teamed up with Abram Hoffer, the director of psychiatric services and a former colleague of Heinrich Klüver, who lent his distinguished support to the prospect of further mescaline research. Hoffer had begun his career as a biochemist studying vitamins and nutrition and was a skilled administrator who succeeded in attracting funding from the Canadian federal government and the Rockefeller Foundation. Smythies joined the pair in 1952 to continue the search for M-substance, working systematically through the compounds intermediate between mescaline and adrenaline. They narrowed their search to substances that ‘produce psychological disturbances similar to mescaline’, for which they coined a new term, ‘hallucinogens’. ‘As Klüver has observed,’ they explained, ‘when we take these remarkable compounds we enter a world beyond language’, which must be expanded to accommodate them. The new category at this point included mescaline, LSD, harmine, ibogaine and hashish.90

As their investigations proceeded they made the curious discovery that asthmatic patients who injected themselves with adrenaline occasionally reported odd, short-lived hallucinatory effects, particularly with old pharmacy stock that had taken on a pink colour. This turned out to indicate the presence of adrenochrome, an unstable oxidisation product of adrenalin first identified in 1937 and suspected to be present in trace amounts in the human body. Its molecular structure was based around an indole nucleus, a characteristic shape combining two rings that was shared by all the recently designated hallucinogens. Hoffer, Osmond and their wives self-experimented with small amounts of the substance, which turned out to be painful to inject unless mixed with blood from the subject’s vein. After a larger dose Osmond noted swarming dots across his visual field: they ‘were not as brilliant as those which I have seen under mescal, but were of the same type’. He felt that he was ‘in an aquarium among a shoal of brilliant fishes. At one moment I concluded that I was a sea anemone in this pool.’91 When he left the laboratory, the world seemed ‘sinister and unfriendly’; he was disconnected from his colleagues and ‘felt no special interest in our experiment and had no satisfaction at our success, though I told myself it was very important’.

Hoffer, on a large dose of 5mg, had a similar sense of alienation – ‘I didn’t have a flicker of feeling’ – and ‘began to wonder whether [he] was a person anymore’.92 They concluded that they had both experienced the depersonalisation associated with psychosis and consequently that ‘adrenochrome is the first substance thought to occur in the body which has been shown to be a hallucinogen’.93 This demonstrated, at the very least, that ‘M-substance could exist’ and that it might produce ‘a wide variety of clinical pictures’.94 It could be the cause of schizophrenia; it could also lead to its cure.

Based on notes that Smythies had brought with him from London, he and Osmond worked up a paper that set the potential consequences of their researches in a broader frame. Psychological medicine, they wrote, currently stood where physical medicine had in the eighteenth century; the task facing it was ‘the replacement of a huge amount of inspired guesswork . . . by an ever increasing amount of surer knowledge based on the careful disciplines of science’.95 At the same time, it was crucial to recognise that the mental phenomena with which they were dealing were not mere pathologies and their patients were more than ‘skinfuls of psychochemical automata’.96 The new biological psychiatry needed to accommodate subjective experience, bringing brain and mind into a new synthesis. The horizons of human potential were expanding, illuminated by a range of fields from electronic computing to extra-sensory perception, captured in Carl Jung’s notion of the unconscious mind as ‘a vast, strange and beautiful inner world more akin to the Eastern view of man’. Such vistas could readily be experienced by anyone prepared to submit themselves to a dose of mescaline, and the authors ‘would have thought that anyone, concerned in devising systems of psychology based on the unconscious mind, would have utilized such a prolific source as mescaline offers, but none has yet done so’.97

Osmond and Smythies’ paper was accepted by the Hibbert Journal, a British quarterly which since 1902 had published scholarly essays on religion, theology and philosophy. One of its long-time readers responded with an enthusiastic letter to the paper’s authors. If Osmond or Smythies were ever passing through Los Angeles, Aldous Huxley would be most interested in trying mescaline.