TWO

The Texas Gulf Coast

FIRST LANDFALL

Early April 2015

Common Yellowthroat

To the green mist of the cypresses and the moving clouds of the swallows we could add the movement of the stars as a sign of the sure approach of the spring. With all the galaxies and planets and stars, the solar system was setting the stage.

—EDWIN WAY TEALE, North with the Spring

The first port of call for many trans-Gulf migrant songbirds in spring is the coast of southeastern Texas, and that is where I plan to meet them. At the end of March, I depart Maryland and over three long days drive to Mad Island, on the Texas coast between Freeport and Corpus Christi. About sixty miles south of Houston, Mad Island is where I’ll meet the vanguard of the northbound migrants. My declared field trip focus is songbirds, but spring on the coast of southeastern Texas is the height of distraction for the curious naturalist because of its abundance of waterbirds, wildflowers, snakes, lizards, and more. At Mad Island, in fact, I’ll learn more about coastal prairie than I will about songbirds, which have been slow in arriving stateside this particular spring. Every turn of my trip, as I will learn, will introduce me to both little-known ecosystems and the people working to conserve these habitats and the diverse bird communities that depend upon them. I have come for songbirds, but I’ll encounter much more.

Mad Island is not, despite its name, an island at all but a tract of prairie overlooking Matagorda Bay and protected from the Gulf by the long, narrow barrier island that runs nearly unbroken southwestward to the border with Mexico. The Clive Runnells Family Mad Island Marsh Preserve, a seven-thousand-acre tract of remnant coastal prairie under the management of the Texas chapter of the Nature Conservancy, lies just southwest of the hamlet of Wadsworth. This preserve, the southernmost point on my circuit, was the official starting point of my journey north to Canada. Here I visited a bird-banding project of the Smithsonian’s Migratory Bird Center (SMBC). Directed by Peter Marra, a Smithsonian colleague, the SMBC studies the ecology and conservation biology of migratory birds in the Western Hemisphere. A SMBC field team seasonally stations itself at the preserve, which generously allows the researchers to do their work here. Marra had advised me to visit the bird-banding projects at Mad Island and at Grand Chenier, Louisiana, to discover what’s being done on the ground to investigate the spring migration of songbirds across the Gulf of Mexico.

With the Colorado River estuary to the east, Matagorda Bay to the south, and Tres Palacios Bay to the west, the Nature Conservancy reserve at Mad Island is a bird heaven year-round. During one recent winter, in fact, the wetlands and rice fields of the Mad Island region supported more than two hundred thousand waterfowl, and Mad Island is known for periodically generating the largest species list of any regional Christmas Bird Count (CBC) in America. The annual CBC, sponsored by the National Audubon Society, is the nation’s longest-running citizen-led annual birding event. Groups of volunteer birdwatchers all over the country count the birds they see and hear within a designated “count circle” fifteen miles in diameter on a designated day between mid-December and early January; more than two thousand such counts are conducted across the continent each year. CBC records on the changing status of winter bird populations have been compiled into a century’s worth of field data for researchers. Whereas the CBC censuses wintering bird populations, my arrival at Mad Island was timed to match the return flight north of many birds that wintered to the south. In preparation for the coming returnees, I set up my tent on the edge of a broad expanse of coastal prairie, just a short drive down a sandy track from the banding station at the coast.

MIGRANT WINTER LIFE IN THE TROPICS

When I showed up, the bulk of Neotropical migrants that the Mad Island banding crew awaited were still down in the Tropics, and I wondered whether the evolutionary origins of these migratory species were northern or southern. Although the details are messy, recent evolutionary analyses indicate that most Neotropical migrant lineages evolved in the temperate zone and subsequently adapted to spend the winter in the Tropics. Wood warblers are a mixed bag: most sublineages of the group evolved in North America, not the Tropics. So some birds evolved in the temperate zone and shifted their wintering habitat south, while others evolved in the Tropics and shifted their breeding habitat north, as originally sedentary lineages began to migrate to follow the seasonal availability of resources. The most likely factor motivating their transition to the migratory habit was the cycle of glacial advances and retreats over the past 2.5 million years. Glaciation’s major impact was the enforced relocation of breeding ranges for virtually all the North American songbirds, and it also had major influences on rainfall and seasonal drought in the Tropics.

What is life in the Tropics like for Neotropical migrants? The migrants have to share their tropical habitat with the abundant local resident birdlife, and they are in this habitat during the dry season, when resource levels are depressed. The migrants likely struggle to establish a winter foraging space, and they must work hard to prepare their bodies for the return flight north and the demands of nesting and raising offspring.

Many migrants seem to select a winter habitat in the Tropics that comes as close as possible to their habitat in the north temperate and boreal zones of North America, but there are limits to their ability to match habitats between the temperate and tropical zones. The tropical flora is different, the days are shorter, the weather typically is warmer, and the food resources differ, offering substantially more fruit and nectar than the northern habitat does. The differences probably outweigh any similarities the birds are likely to find, and accordingly some species change their feeding behavior between summer and winter—those that are specialized insect eaters in the north shift, in some instances, to consuming nectar or small fruits in the Tropics.

Migrants’ social behavior also can differ between north and south. Most Neotropical migrants establish breeding territories in the north, with a male-female pair occupying each territory and raising their young there. In the Tropics, by contrast, some species establish solitary (one-bird) territories for much of the winter, whereas others establish no territory at all, instead roaming about and joining other foraging species of migrants and nonmigrants. Some migrants, for example, take up with multispecies flocks of birds that regularly follow army ants, pursuing the invertebrates that flee before the moving ant columns. Other species become seasonally sociable with their own kind, foraging in monospecific flocks on flowering and nectar resources. And some species are reported to roost in single-species groups at night.

Those that join mixed-species foraging flocks in the Tropics are part of a phenomenon that seems widespread in the Tropics of both the New and the Old World, one that may be driven, at least in part, by the threat of predation by bird-eating raptors, snakes, and mammals. The mixed flock occupies a large foraging territory each day, and as the group moves about, individual birds or bird pairs join up or drop out of the flock as it passes through their home ranges. A wintering thrush might forage alone on its solitary home range but join a flock to forage with the group as it passes.

Studies of Kirtland’s Warbler have demonstrated that winter conditions influence subsequent breeding productivity. Sarah Rockwell and her collaborators, for example, have shown that ample rainfall in March on the Kirtland’s wintering ground in the Bahamas led to both earlier arrival by males back in Michigan and the production of more fledglings per male. So winter conditions for a warbler in one location can have measurable carryover effects on breeding results in a distant locale. Similar results have been shown for American Redstarts that winter in the Caribbean and breed in eastern North America.

During the long and lean season in the Tropics, each migrant songbird has two clear objectives: to avoid being eaten by a predator and to maintain (or improve) its physical condition in readiness for the migration north and the breeding season to come.

THE COASTAL PRAIRIE ECOSYSTEM

Mad Island lies at the heart of the coastal prairie ecosystem that once dominated southwestern Louisiana and coastal Texas. The ecosystem, decimated by development, once included extensive tallgrass prairie, wetlands, and patches of gallery forest. Today, it is one of the most endangered natural habitats in all of North America. This narrow band of prairie lies just back from the coastal marshes and once stretched in an arc that paralleled the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. But less than 1 percent remains in its original state. Most has been degraded by cattle grazing, rice farming, sugar cane monoculture, oil and gas development, and creeping urbanization. Public and private restoration of prairie lands is crucial to the future of this critically endangered ecosystem, which is home to an array of birds—including the Mottled Duck, Attwater’s Prairie-Chicken, White-tailed Hawk, Crested Caracara, Scissor-tailed Flycatcher, Painted Bunting, and Dickcissel. Prior to western settlement, this unique tallgrass prairie evolved through the influences of seasonal rainfall, periodic fire, and grazing by Bison and other wild ungulates; native grasses thrive under conditions in which they can outcompete woody plants. In the intact areas of the coastal prairie, native grasses such as Big Bluestem, Indiangrass, Eastern Gamagrass, and many native wildflowers dominate. These species cannot tolerate heavy year-round grazing by domestic cattle, which encourages the invasion of exotic annual grasses such as Vasey Grass, from South America, and Johnson Grass, from the Mediterranean. Natural prairie is dominated by long-lived perennials, and, with a few exceptions, annuals are rare in undisturbed prairie sod.

Most Neotropical migrant songbirds that cross the United States–Mexico border in spring have destinations far north of Texas. That said, a few do settle to breed in the Texas coastal prairie, including the Scissor-tailed Flycatcher, Common Yellowthroat, Painted Bunting, and Dickcissel. The first of these, with its long swallow tails and apricot underwings, is among the loveliest birds in America. It winters in open country in southern Mexico and Central America and breeds in the southern Great Plains all the way down to Mad Island, where it is one of the most familiar birds along rural roadsides. The Common Yellowthroat—one of my quest group, the eastern wood warblers—winters as far south as Panama. The only wood warbler to breed right along the Gulf Coast, this diminutive, bandit-masked songster is North America’s most widespread wood warbler. The yellowthroat is unusual in breeding in marshes and shrublands, places that often lack woods or trees. Most breeding wood warblers prefer forest as a nesting habitat, and Mad Island’s patches of low coastal scrub woodland are inadequate for that purpose.

Male Painted Buntings show a splashy patchwork of bright colors, whereas the females are plain pale green. The species winters in Mexico, Central America, south Florida, and the Caribbean, hiding in scrub woodland and seen most frequently when visiting a backyard feeder. For birders, the male Painted Bunting, which sings a musical song reminiscent of that of the more widespread Indigo Bunting, is one of the most sought-after species of the Deep South. The Dickcissel, with its black bib, yellow breast, and chestnut wings, is one of the omnipresent songbirds of the prairie, giving its staccato six-note song from atop shrubs all day long. For birders visiting southeastern Texas for the first time, the sight of these four species out in the open prairie habitat is entrancing.

BIRD-BANDING

Called ringing in Europe, bird-banding has been a means to study bird movements since 1803, when John James Audubon tied silver wire around the legs of nestling Eastern Phoebes in Pennsylvania and found two of them back on their nesting site the following spring. Today, 6,500 bird-banders are active in North America. All operate under the auspices of the Bird-Banding Lab at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, in Laurel, Maryland. The lab, founded in 1920, is a collaboration between the U.S. Geological Survey and the Canadian Wildlife Service, and it provides the bird-banders with free numbered aluminum bands that they affix to the leg of each captured bird for permanent identification. Each year the lab provides bird-banders with fresh supplies of bands, and in return it receives detailed records of the birds banded over the previous year. The lab keeps computer files on the more than one million birds banded each year and the seventy million birds that have been banded over the past nine decades. Of greatest interest are the “recoveries”—banded birds that have been retrapped at a subsequent time or place. It is recovery data that yields information on the movements of birds across the continent.

Traditionally, banding studies focus on productive “migrant traps”—areas where migrating songbirds concentrate because of optimal geography and habitat. For instance, from 1958 to 1969, Chandler S. Robbins, James Baird, and Aaron M. Bagg situated their Operation Recovery program at several coastal locales in the East to track songbird migration, and these initiatives led to the establishment of permanent bird observatories, such as Manomet, in coastal Massachusetts, and Point Blue, near Point Reyes, California. Several universities carry out seasonal bird-banding operations as well, but most birds are banded by hobbyist banders in neighborhood woodlots and regional parklands. Collectively, these groups and individuals have generated invaluable information on species longevity and how large-scale weather patterns influence the seasonal movement of songbirds, both of which help scientists to understand the evolution of successful migratory strategies.

Dickcissel

Mad Island’s isolated patches of coastal woodland are ideal for spring bird-banding because they draw in arriving migrants, which find the vast expanses of prairie grassland and marshland unsuitable as stopover habitat.

Over dinner on the night of my arrival, I meet the Smithsonian project team: Emily Cohen, a postdoctoral researcher; Tim Guida, project technical officer; and four assistants. These dedicated bird researchers use a spacious, modern hunting lodge donated, along with the reserve land itself, by the Runnells family in 1989. The compound includes a house with a large, elevated porch, a barn, and outbuildings. Floor-to-ceiling picture windows look out across Mad Island Lake, a birdy coastal estuary, and surrounding coastal saltmarshes. Vistas of prairie and marshland spread out before us.

Mad Island is the southernmost banding project for Neotropical migrants approaching the United States. By the time of my arrival, the Mad Island team had documented a couple dozen species of Neotropical songbird migrants—including Indigo Bunting, Blue Grosbeak, and Hooded, Kentucky, and Swainson’s Warblers—dropping into its little patches of coastal scrub woodland. Amid the scrub, the researchers had strung mist nets: forty-foot-long black nylon nets spread tautly between two poles. Mist nets act like large spider webs, harmlessly entangling unsuspecting birds who fly into them without ever seeing them. Thus far, only a few birds were arriving daily, and the team was still waiting for the first big wave of migrants.

The little crew was intrepid, working in a habitat with strong winds, relentless sun, swarming mosquitoes, and venomous snakes. Their long days started well before dawn, which sometimes brought the excitement of trembling nets full of new arrivals and other days only the frustration of nets filled with dried leaves blown off the sheltering trees. Each hour the team checked the nets, mounted along narrow pathways cut through the scrub. Every netted bird was carefully removed, placed in a cloth holding bag, and brought to the project tent for banding. All birds were weighed, measured, and studied for fat deposition, age, and sex. From some birds, the team also collected a small blood sample to check for blood parasites and plasma metabolites that could reveal physiological condition. The team also searched the birds for ticks, which they preserved for study by taxonomic and epidemiological experts. After this meticulous treatment, the team released the birds unharmed to continue their northward journey.

This banding camp operates for nine weeks each spring, and by season’s end the team knows all the resident birds of Mad Island as well as the passage migrants that have migrated through. The team told me that the main benefit of working on the banding project is the unlimited access that participants have to the Mad Island coastal prairie environment, with its rich diversity of wildflowers, snakes, frogs, butterflies, mammals, and birds.

During my second morning at the banding camp, a low cloudbank hangs on the coast. A Texas Spotted Whiptail, a nine-inch lizard with green dorsal stripes and small, pale spots on its flanks, searches for a patch of warm sand on the sandy access track to the station. These lands have many reptiles and amphibians as well as birds. This one speeds off in a colorful flash upon my approach.

The first bird netted this morning was a Nashville Warbler. Tim Guida carefully banded and measured it, a process that took about five minutes. Done, he extended his arm with his hand lightly enclosing the small yellow, olive, and gray bird, then slowly opened his fingers. The warbler lay on its back for a couple of seconds before sensing its freedom. It quickly flicked its wings and darted off to a low bush a few paces from the banding tent. It preened for a few moments, collected itself, and flew strongly over the canopy of the scrub and out of sight, its aluminum band glinting in the sunlight. The Nashville Warbler is a boreal forest breeder on its way not to Tennessee (despite its name) but up the Mississippi Valley to the North Woods. This bird, and millions like it, would be preceding me northward in the weeks to come. I hoped to encounter more Nashville Warblers singing on their territory in northern Ontario in mid-June.

As the sun rose toward its zenith, the glare off the sandy expanse of the clearing grew intense; I squinted out from the banding tent over the narrow shipping canal to the expanse of Matagorda Bay, where dredge boats were harvesting oysters and flocks of gulls hovered overhead in hope of snatching something edible. The southwest wind started to build until, just before noon, Guida decided to halt netting. An inevitable challenge of working on the coast is the onshore wind that can blow steadily off the water, presenting problems for bird netting even on otherwise pleasant days. Windblown leaves tangle in the mist nets, which themselves lurch around and snag in vegetation. Because they are somewhat fragile, the nets can tear, making them more visible to birds and thus less effective at catching them. Guida instructed the team to close the nets, which they secured with colorful strings.

Nets closed, the team and I went out to explore the preserve, walking on sandy roads through the property and visiting Skeeter and Pintail ponds. We saw many resident marsh birds but were surprised by what we found far from any woods: two male Orchard Orioles and a Wood Thrush, holed up in a single isolated shrub. This is the type of place an exhausted songbird migrant ends up when it descends into an inappropriate habitat after a long trans-Gulf flight. At least these birds had made it to terra firma, done with their crossing of the open sea.

A pair of White-tailed Hawks put on an aerial show for us over the low grassland—the climax of the afternoon. They have the bulk of a Red-tailed Hawk but unmarked all-white underparts, a gray dorsal surface, red-brown shoulder patches, and a broad white tail marked with a neat black subterminal band. The species flies with its wings tilted upward, distinguishing itself from a distance by this unusual silhouette. This big nonmigratory tropical raptor reaches the United States only in the coastal prairie of southeastern Texas, but its global range extends all the way to southern Argentina. Here in southeastern Texas, it is a local coastal prairie endemic—one of those species confined to a tiny corner of the country. For that reason, few American birders ever see it.

The next morning, Cohen and the preserve manager, Steve Goertz, continue my behind-the-scenes tour of the preserve. The coastal prairie at dawn is very birdy. a pair of Crested Caracaras hang out in a low tree that held their nest last year. Strongly patterned and wary, the pair makes off before we get close enough for a photograph, exhibiting in flight their strange silhouettes, with long necks and steady, rowing wingbeats. Several coveys of Northern Bobwhite quail race across the dirt track in front of Goertz’s truck as we slowly rumble over the prairie, and a Loggerhead Shrike perched on a low fence line speeds off with whirring wings that flash black and white in the morning sun.

The relative abundance of Northern Bobwhites and Loggerhead Shrikes here in southeastern Texas was a pleasant surprise because they have disappeared from virtually all their former range in the eastern United States. Why are they common in southeastern Texas? Biologists think it is due to the abundance of invertebrate prey available here for these two open-country birds. Solutions to large-scale conservation problems can arise in environments such as this one, where a juxtaposition of beneficial environmental factors and benevolent human interventions produce a positive result. Yet finding such solutions is a matter of focused trial and error. No one had ever restored a Texas coastal prairie before Goertz and his small team initiated their program, deploying selective grazing and judicious use of fire and herbicide to control tenacious invasive plant species. The restoration of Mad Island as a native coastal prairie will require decades of effort. But by saving this land from development, the Nature Conservancy has already taken a major step for its protection.

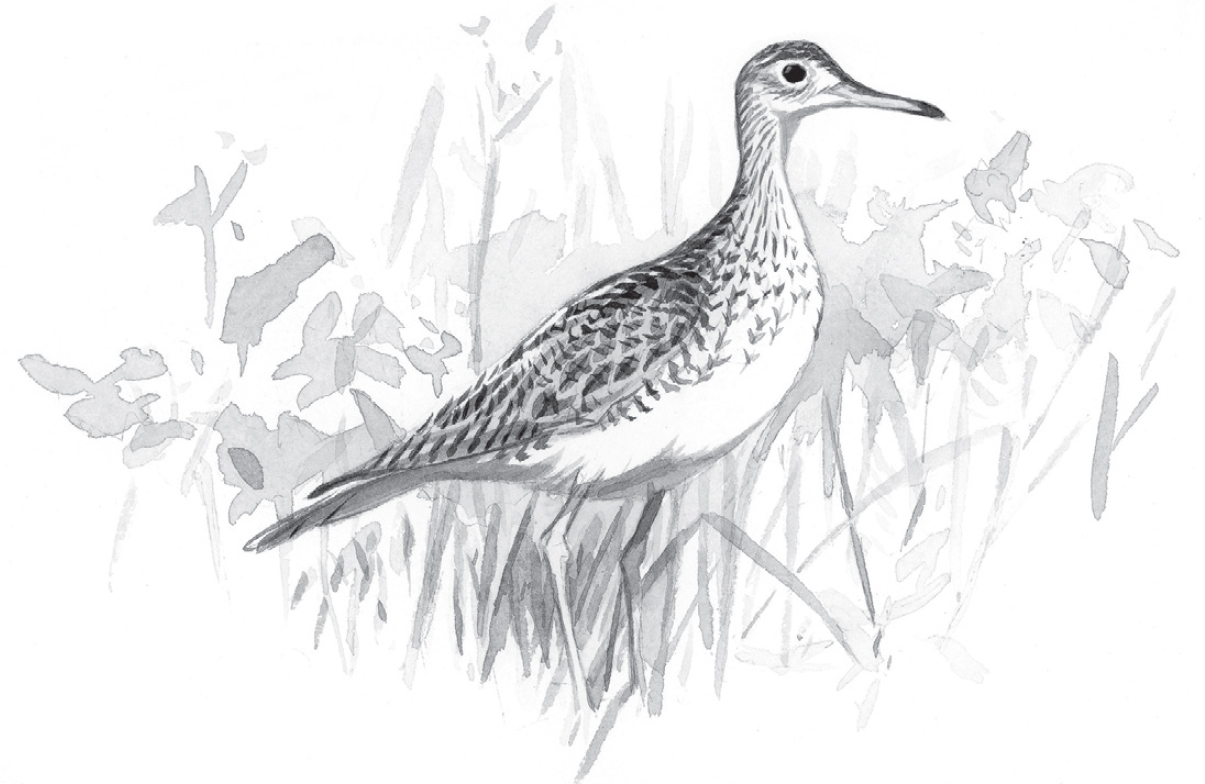

The highlight of the third morning at the preserve was a pair of Upland Sandpipers that flew up from a patch of short grass, giving their weirdly musical, trilled, rising and falling flight song. These grassland specialists had recently arrived from their wintering grounds in the pampas of Argentina. Because of declines in grasslands, eastern birders don’t get to hear this song much anymore; today the species is mainly found in the prairie country of the northern Great Plains.

Upland Sandpiper

THE NATURE CONSERVANCY’S PRESERVATION OF PRIVATE LANDS

Since its founding in 1951, the Nature Conservancy (TNC) has focused on preservation of private lands in the United States. To date, TNC has ensured protection for more than twenty million acres of private lands and managed these properties to maintain or enhance their ecological value. Because of its strong national reputation, TNC often receives donations or bequests of private land of significant natural value, and the Runnells family’s land was one such property. While donations such as this one are an effective method of achieving conservation if resources are available, long-term costs are incurred in the maintenance and management of private lands. Sometimes TNC simply purchases land outright and then passes the property to a state or federal entity to carry out long-term management.

Aside from the purchase and maintenance of property, TNC has also pioneered conservation easements on private properties that both benefit landowners and ensure perpetual protection of natural values. Easements enable land managers to achieve targeted objectives while keeping land under private ownership, and they can help conserve tracts of forest, protect water quality and scenic vistas, and create wildlife habitat. Typically, TNC purchases easement rights from a landowner and thus achieves a conservation “win,” while the landowner receives a tax benefit. The United States has a large network of local, state, and national protected lands, but by adding a portfolio of private lands, TNC has expanded the reach of conservation across the country. Today more than 40 million acres in the United States are covered by private conservation agreements, compared to 10 million acres under state protection and 170 million acres conserved by the federal government. Private protection is particularly important for preserving lands with very specific conservation values that otherwise aren’t protected by the governmental sector—as is true of Mad Island’s critically endangered Texas coastal prairie.

The 2015 netting season at Mad Island lasted from mid-March to mid-May. The team banded 1,972 individual birds of 81 species, including local residents and Neotropical migrants. The season’s highlight was a big arrival of Dickcissels, which for several days perched atop virtually every bush, plus rare species including ten Golden-winged Warblers and an out-of-range Western Tanager and Yellow-Green Vireo. Overall, the team observed 230 species of birds during the spring. The 2015 season was memorable to the field team because it was particularly wet, generating abundant wildflowers and many Cottonmouth snakes but no huge flights of Neotropical migrants. No matter the spring weather, though, the team collected another year’s worth of spring migration data. As results from more years become available, bird-banding projects such as the one at Mad Island will help us to refine our understanding of northbound songbird migration under various weather regimes and wind patterns.

My stay at Mad Island gave me a small taste of the songbird migration to come. I learned about the coastal prairie and saw first-hand private lands conservation in action. I was now headed up the coast of Texas to another birding hotspot, at a time when birds would start flooding into the coast.