11

Even with all the action I had selling instruments and my head-spinning proximity to world-class artists, I was still pursuing my own music. LA in the seventies was still a place where you could gig steadily, if you had a solid band.

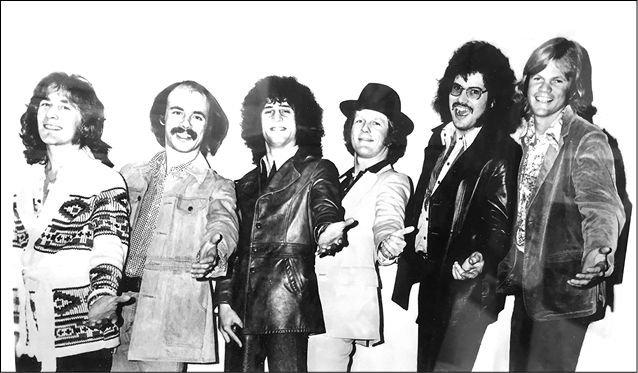

Ed Robles (AKA Gabriel Black) and I joined forces with the Juke Rhythm Band, which included the late great John “Juke” Logan on blues harp and piano, my buddy Dan Duehren on bass, Joe Yuele on drums, and the phenomenal Rick Vito on lead guitar. Thus, we became the Angel City Rhythm Band.

Everyone in the group was musically very strong. Our sound was a mix of James Brown–style funk grooves with an overlay of blues harp. Juke Logan was an excellent writer, and we all took turns singing lead. In retrospect, though, not having one lead singer probably made it hard for record companies to know exactly how to sell us. Our vocals would go in different directions almost song by song depending on who was singing.

Angel City Rhythm Band. (Photo by Norman Harris)

Our versatility didn’t affect our popularity in the clubs. We were busy. We were the house band at a club on Van Nuys Boulevard called The Rock Corporation. When Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers first formed, they didn’t have any gigs, and we were able to secure them a gig there before they began to play a lot of original tunes. They mainly played Rolling Stones cover tunes and other rock hits.

•••

I’ll never forget one particular night at the club. We were in the middle of a tune and one of my friends came running in, yelling, “Marlene’s water just broke!” I jumped off the bandstand, tore home in my car, picked her up, and rushed to Cedars. It turned out we jumped the gun by a day. My son, Jordan, was born twenty-four hours later.

Though I was thrilled to become a dad, I was wholly unprepared for the responsibility that goes along with it. Because we were still pretty young, Marlene and I foolishly thought we could still continue living life as we knew it and just bring the baby along with us.

Jordan must’ve been a few months old when the band got a gig backing up Dobie Gray, a crossover pop soul singer of the seventies. (Any of you remember the number-one hit “Drift Away” or “The in Crowd”?) We played in Vegas and Salt Lake City, and after a gig in Reno, Marlene and I figured we’d drive home with Jordan. Wearing only the clothes we had on our backs, we saddled up my beat-up old Mercedes at around 2:00 a.m. and hit the road. In a godforsaken place called Miracle City, one of the car’s hoses blew, and we came to a halt in the middle of nowhere. It was freezing! We finally made it to a motel, chilled to the bone, but by then Marlene had decided that it was easier to take care of the kid at home. She decided not to travel with the band to our out-of-state gigs.

Another night, Dan Duehren and I were driving the truck back from a gig at a club in Santa Barbara called the Feed Store, when it suddenly ground to a halt. We’d run out of gas. Luckily, Juke Logan had left after us, and he gave us a ride, along with a gas can, to the nearest gas station. It was pretty desolate out there. When we started pumping gas, some freak in a camouflage outfit emerged from the darkness and started giving us “hippies” a bunch of shit. Danny, no stranger to dishing it out, gave the nutjob some lip back. Next thing I knew, the crazy fucker pulled out a rifle, cocked it, and aimed it right at my head. I was high as a kite, and my life flashed before my eyes. I had two kids, (my daughter, Sarah, had just been born) a loving wife, a house, a small business, and here I was—about to die in the middle of nowhere, at the hands of some maniac, for reasons unknown! I loved my art, but I didn’t love it enough to die for it. Somehow we talked our way out of it, and even Danny was quiet for the rest of the ride to LA.

Yes, the life of a working musician! Paying for diapers, formula, and baby clothes also reminded me that, popular as we were, the band wasn’t really bringing home the bacon. Yet. I had hope though. People really dug us. Quite often, respected musicians around town would show up to where we were playing to check us out. Bonnie Raitt was a regular at the Topanga Corral. All good, until . . . she poached Rick Vito from the band! It was a huge loss and it kind of pulled out the rug from underneath us. Rick was such a charismatic player, singer, and integral writer and instrumentalist for the band, things were never quite the same. After Rick left, my buddy John Paulus came out from Florida to play with us, but Rick’s absence was a pretty big hole to fill. We lost momentum.

The Angel City Rhythm Band still played together and occasionally Rick Vito would sit in with us. We were the band of choice for many big name blues artists, but this was considerably after the prime of their careers. We probably backed up Albert Collins about fifty times. He played a 1965 Telecaster Custom with a stripped down finish and always had some kind of sparkly contact paper over the bridge cover. He would turn up his Fender Quad Reverb amp to ten and had a searing, funky tone. He would play everything with a capo in open position, bending and popping those notes with his fingers. His guitar strap was always slung over one shoulder. His expressions during tunes were priceless. He always had a two-hundred-foot guitar cord and would go outside the club onto the street during his solos, and everybody would follow him in. What an original!

Norman playing bass with King Cotton at the Santa Barbara Zoo opening event. (Photo by Marlene Harris)

We also backed Big Joe Turner and Lowell Folsom on many occasions. Other artists we backed up were Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, Roy Milton, Margie Evans (from the Johnny Otis Show), Big Mama Thornton, and many others.

For my fortieth birthday, Rick got Marlene to hire these wonderful a capella singers for my birthday party. Rick knew I loved doo-wop, and I was knocked out by these guys. We put them together with R&B singer King Cotton and, lo and behold, we soon had a very tight musical blues and soul band, with some fantastic vocal harmonizing.

The Texas-born King Cotton is not only a dynamite performer but a serious roots and blues archeologist and “true believer.” Once he and I got together, it was a true meeting of the minds concerning deep blues, rock and roll, and R&B cuts. We even created a radio show called King Cotton’s (White Blur) Show. We decided we would only play the best and most obscure songs. Tunes like “That’s What Love Will Do for You” by Little Milton, “Thread the Needle” by Clarence Carter, and “That’s How Heartaches Are Made” by Baby Washington. I also coproduced a vintage rhythm and blues radio show with the great Billy Vera. Billy is also an amazing singer, guitarist, and showman, and is a vintage rhythm and blues authority. Billy had several hits in the sixties (“With Pen in Hand” and “Country Girl, City Man” with the great Judy Clay). Many years later, he had a monster hit with the tune, “At This Moment.” Many album reissues that have been released over the years have had liner notes done by Billy Vera.

When we lost our bass player last minute to a better paying gig, I stood in on bass. We didn’t have time to bring someone else in, and I knew the chord changes, the arrangements and, more importantly, how to stay out of the way. Lord knows I had access to fine instruments, so I ended up playing bass in the band for two years. It was some of the most fun I’ve ever had, musically.

We were the house band at St. Mark’s Place in Venice, and many people used to sit in with us—guys like Joe Walsh, Lee Michaels, and my good buddy Frank Stallone.

What happened was our labor of love turned out to be more of a regular gig, as we got booked more and more nights during the week. Now I was in my forties, getting up early to get the newspapers, opening the store, and I could not burn both ends of the candle like when I was young. Because the other musicians in the band needed a steady income, I didn’t want to take food out of their mouths, so I stepped aside.

•••

I got into the guitar business because I loved music and I dug hanging out with musicians. And luckily, through my last two bands, I got to back up some of the greatest blues players toward the end of their careers when most of them were working as singles and often requested us to back them up.

It was very cool playing with cats like King Cotton because we were students of the classic era. We backed up Bo Didley a number of times toward the end of his career, on the Santa Monica pier and in clubs downtown. We knew that Bo had recorded an album on Chess with the Moonglows (probably the greatest doo-wop group ever), and we had all the arrangements down, including three- and four-part harmonies, which really blew Bo’s mind. Bo was used to having pickup bands not knowing his tunes, and once we kicked out “I’m Sorry” and “Didley Daddy,” Bo was very impressed with how organized we actually were. He couldn’t believe we’d dug out those deep cuts from his past, and he loved it. Bo’s daughter was also a super-funky drummer, and she often sat in with us.

Once we did a gig with Bo and the crazed comedian Rudy Ray Moore, known as the “Dolomite,” after a pimp he played in some of those black exploitation pictures from the seventies. Rudy also was a reappearing character on the White Blur Show. Rudy was always hysterical! I’ll never forget sitting backstage while Rudy and Bo exchanged “dirty dozens,” each one upping the other with the insults, like “your mother’s so ugly she has to sneak up on a glass of water,” stuff like that. All remnants from the Chitlin’ Circuit era. Those two had us on the floor they were so damn funny.

One exceptional musician who reinvented himself was the great Johnny “Guitar” Watson. He transformed from jump bluesman to funk pimp in the seventies, turning out catchy hits like “Ain’t That a Bitch,” and “It’s a Real Mother for Ya.” Though we never backed him, I used to see him around town at the car wash, driving his customized Stutz Bearcat, dressed in full-on pimp regalia. After he died in 1996, his wife sold me one of his ES-335s and a Strat. I was really excited when she let me have one of Johnny’s full-length fur coats! Inside the coat, sewn into the pocket, were the words Johnny Guitar. I sold the coat to the incredible New Orleans piano player John Cleary (from Bonnie Raitt’s band), and he’s been known to wear that coat in one-hundred-degree weather down in N’awlins.

Johnny Guitar Watson was the exception. A lot of these folks were alcoholics, living pretty much hand to mouth. I’ll never forget backing up Big Mama Thornton at the Starwood toward the end of her career. She had lost a lot of weight and wore these madras shorts and shirt, and had on a fishing cap. Toward the end of the set, she told the audience, “Big Mama’s been real sick lately,” and then she passed her fishing cap around, while we played a slow blues. When she put the hat back on her head, all the change and bills fell out all over the floor. She got down on her hands and knees to pick up those dollars and coins. It was heartbreaking.

Like Levon Helm said, “We’re not in it for our health. The truth was, the music business had changed radically by the eighties. As those great blues artists passed away, disco and programmed beats and samples took over. With hindsight, I realized that The Last Waltz truly was the end of an era. Luckily for me, people still wanted to write songs and perform on guitar!

Gibson 1969 ES-335. (Photo by Jen Angkahan)