18

I'm known around this business as a man willing to put his money where his mouth is. Believe it or not, I actually tend to be somewhat conservative. Often I have had opportunities to buy instruments that at the time seemed like all the money in the world. In almost every case I ended up regretting not purchasing the instrument, because the overall escalation in prices has been so dramatic, and instruments that originally seemed to be so expensive turned out to be dirt cheap.

In 1968 and 1969, late-1950s Sunburst Les Paul Standards were going for around $800. I know this seems impossible, but remember that they were only ten years old at the time! It seemed like so much money, and accounting for inflation, $800 was equal to about $5,200 today, which is still pretty damn cheap, considering. I remember passing on a few, and it was agonizing. Dot neck ES-335s were going for about $300. Blackguard Telecasters and 1950s maple neck Stratocasters were going for $300–$400. I even remember a time in my first store when I had about six pre-CBS Strats on the wall. This was in 1975, and you could have had your choice for $750.

I was playing in my band Katmandu in 1969, and a friend of mine, Jeff Wityak, who now lives in California, called me to say he had a line on a Sunburst Les Paul. An old fireman who lived near his house in South Miami owned it. I went over to Jeff’s place, and we both drove to see this old man just a few miles away. I can still remember going into his house and watching the man pull out a brown Gibson cardboard soft case. Inside the case was one of the cleanest, flamiest ’Bursts ever. The flames were extremely wide and were on a chevron. This ’Burst was completely out of control. I really didn’t know what I was looking at, but I wanted this guitar in the worst way. I can still see the guitar in my mind.

I asked the old-timer how much he wanted and he said $1,500. This was twice what any of these would have gone for at the time. I tried my best to negotiate, but he was a stubborn son of a bitch. He would not lower his price a dime. I think he enjoyed teasing us with it, and he knew I really wanted it. But I wouldn’t budge, either. I had enough money but could not see myself paying twice the guitar’s value.

For a few years we kept contacting the man, hoping he would reconsider. This was just not going to happen. One day we called and his phone number had been disconnected. We went to his house and he no longer lived there. I’m sure he passed away long ago, and somewhere that guitar still exists. To this day, I dream about that guitar.

Another guitar that I remember about the same time, also in Miami, was an early Gibson Byrdland. This was not like any Byrdland I have ever seen. It was in factory-black finish with a headstock similar to an F-5 mandolin, with the curlicue and a flowerpot. Once again I asked this man how much he wanted, and he said $1,500. This seemed like so much money. I tried to negotiate but was unable to make it happen. Somewhere in South Florida, this guitar still exists. I know that someday I’ll see it again.

Unfortunately there are too many of these stories. Sometimes people take pleasure in torturing would-be buyers. In retrospect if I only stepped up, I would’ve had them, but my conservative nature took over, and I was unwilling to speculate and pay over market value. These guitars seemed so overpriced at the time, but I just could not pull the trigger and these regrets I will have forever.

In LA, through my relentless cold-calling folks in the Musician’s Union roster, I found a man named Stanley “Curly” Clements. I bought several instruments from him. One axe I didn’t buy was a 1930s Martin Herringbone D-28 with a Bigsby neck. I was such a stickler for originality, I felt the Bigsby neck was a modification and a sacrilege. I just didn’t see the value in such an instrument, because I didn’t understand the importance of Paul Bigsby’s history in the electric guitar world, as well as its impossible rarity. Through the years I owned a couple of Bigsby guitars and steels, but I passed on quite a few others. By the time I realized what I didn’t buy, it was gone.

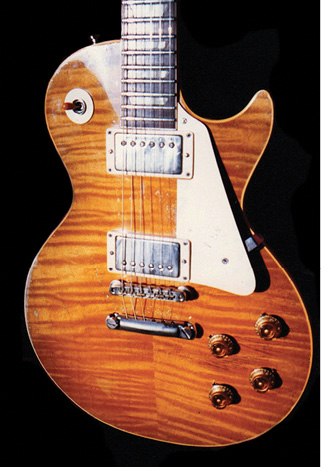

Gibson Les Paul. (Photo courtesy of Norman Harris)

Another instrument I was not aware of at the time was a beautiful prewar Gibson Advanced Jumbo, which was Gibson’s rosewood answer to the Martin D-28. Some time in the mid-seventies, this guitar was offered to me at $2,500. I just did not realize the rarity of what I was looking at. I countered at $1,500 for the guitar, which seemed high at the time. Once again I missed the boat and could not see into the future. Another costly mistake, but who knew?

A number of years later, a friend offered me two late-1950s Les Paul Standards. One was a terrifying flamy Sunburst Les Paul, and the other was a late-1950s Goldtop with P.A.F.s that had a floral pickguard like an ES-295. Both guitars were totally mint. I knew these guitars were unbelievably rare, but I just could not get with the price. If only I had a little more foresight . . . If only . . .

Sometimes you get a slew of great guitars and miss just one special instrument. Because I was one of the only stores in Los Angeles to specialize in vintage instruments, from time to time I would receive a call from someone selling their guitar or their guitar collection. I almost had a monopoly at the time for buying vintage guitars in Los Angeles.

Other stores would refer sellers to me, and more than often, I gave them a kickback or a fee for sending people my way.

My old friend and bandmate from the Angel City Rhythm Band, Dan Duehren, was working with me at the time. We received a call from a gentleman in the Santa Barbara area who had some guitars to sell. He told me about a few instruments he had, including several old Fenders. One was a sunburst stacked-knob Jazz Bass. There were a couple of Sunburst Stratocasters and there were a few other Fenders—a custom-color Jazzmaster (Lake Placid blue), a candy-apple red Jaguar, and a Sunburst Fender electric twelve-string. He said he had a few more things and would show me if I came over. He said he used to work for Fender and at one time had his own store. Danny had a pickup truck, so we got directions and couldn’t hit the road fast enough.

When we arrived we were blown away. He had what he said, but he also had about thirty more instruments. There was an early 1960s L-5 CES Sunburst, dot neck ES-335, a blond 1950s Fender electric mandolin, a J-200, and many more, including some vintage Fender amps. Almost everything was fully original and in remarkable condition. We spent a few hours assessing the guitars and then went into negotiation. Once again he knew what he had, but he was happy to be able to sell so many instruments at once. This was around 1980, so even though it seemed expensive at the time, by today’s standards it was a bargain.

After we consummated the deal, we wrote a check and loaded the instruments in Danny’s truck. Just before leaving the gentleman pulled out one more bass. He said this was his main instrument and he was not ready to let it go. He wanted me to see it in case he decided to sell it at a later time. It was in a tweed case, and when he opened it up, there was a beautiful 1955 Precision Bass. This was a contoured-body bass like Sting’s, but what was truly unbelievable was the bass was a light pink color with gold parts. Danny and I both nearly fell over. The bass wasn’t super-clean, but it was obviously original and the condition was very good. He said it was custom-made for him. He wouldn’t sell the bass at the time, and I continued to call him from time to time, but he would never sell it. After several years, the phone number and address were no longer any good. It is a bass I still dream about. I won’t mention the name of the man because I don’t want anyone else to find him and buy the bass. I still have hope that if he is still around, I may one day own this bass!

I can go on with these stories for days, but now I will tell you about one of the biggest ones that got away. One day a friend of mine, Gerry McGee of the Ventures, came into the store and told me that his friend Delaney Bramlett was considering selling his all-rosewood Telecaster. This was not just any rosewood Telecaster. This was George Harrison’s “Let It Be” rosewood Telecaster. George had “given” it to Delaney many years before. At the time I believe Delaney needed the money. Gerry took me to Delaney’s ranch house in the valley and Delaney showed me the guitar. He had used the guitar over the years and even routed it for a humbucking pickup in the neck position.

I believe I possibly could have purchased the guitar for about $60,000. I had been aware of it for a number of years. There was a bit of lore that came with this guitar. Delaney received the guitar as a gift from George. However, I had been told that George thought of it as only a loan. I probably could have closed a deal on that particular day. My only fear was that after I purchased the guitar, George might come to me and want it back! (This was not unlikely, believe it or not. George always drove a hard bargain.) Gerry and I spent a few hours with Delaney, but I got cold feet. How could I refuse George if he wanted the guitar back? A few years later, the guitar was sold at auction for quite a bit more than $60,000. I believe it was purchased posthumously for George’s wife, Olivia, by Ed Begley Jr. To this day it is back with George’s other guitars in Olivia’s possession, and that is a good thing.