1

Ice Age Bones

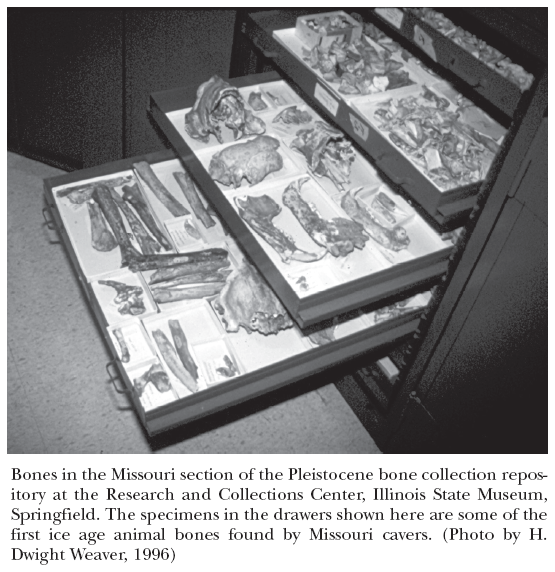

A surprisingly large number of Missourians are engaged in cave exploration. . . . These explorers have recently developed a special interest in the bones that are found in many caves, and new finds are reported so rapidly that it is difficult to keep pace with their identification and analysis.

—M. G. MEHL, Missouri’s Ice Age Animals, 1962

Since the days of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the bones of ice age animals have been found all across Missouri. They remind us that many great beasts, now extinct, once roamed this land, including creatures such as woolly mammoths, mastodons, giant ground sloths, peccaries (ancient piglike animals), moose-elk, bison, long-legged dire wolves (which must have been terrifying), enormous cave bears, ferocious saber-toothed cats, huge American lions, and giant beavers. A surprisingly large number of fossil animal remains have been found in Missouri caves embedded in clay and gravel sediments. Some remains have been discovered lying exposed on cave floors right where the animal died thousands of years ago. In addition, the clay floors and stream banks of some caves preserve the tracks, dens, and claw marks of extinct animals.

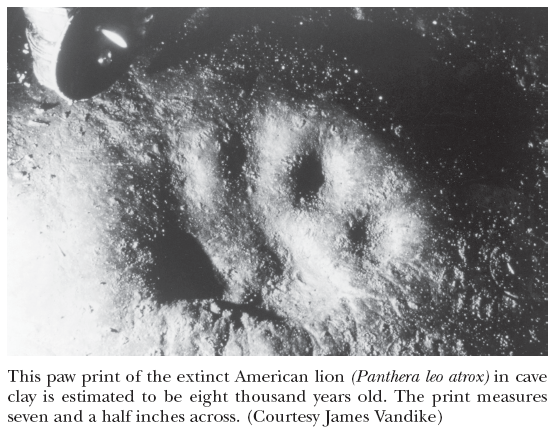

Several decades ago cavers discovered the footprints of the extinct American lion in a cave near the Missouri-Arkansas border. The species has been dead for more than eight thousand years, yet the tracks looked so fresh, according to the cavers, that seeing them raised the hair on the backs of their necks. It was easy to imagine the animal was still alive and somewhere close by in the cave. Many caves have the ability to preserve fossil remains and tracks for a very long period of time. Another set of remarkable animal tracks preserved in clay were found in a cave near Perryville south of St. Louis—footprints believed to be those of the ice age jaguar or saber-toothed cat.

These kinds of discoveries make experienced cavers very cautious when exploring a wild cave they have not visited before or a cave known to be virgin. They pay attention to where they put their feet, because fossil imprints left in soft clay can be easily and quickly destroyed. One can only wonder how many fossil tracks of ice age, or Pleistocene Epoch, animals have been destroyed in Missouri caves over the past 150 years by careless people.

A diverse group of large animals existed here between ten thousand and two million years ago. The undisputed champions for size were members of the elephant family. The most abundant were the American mastodons and the more common ice age mammoth. These enormous creatures shared their environment with the giant North American beaver, a muskratlike animal as large as the modern-day black bear. There were two species of ground sloth, one of them a giant, with enormous claws designed for digging and self-defense. The animal weighed a ton and stood twelve feet high on its hind feet.

Another impressive creature was the giant short-faced cave bear, which stood five and a half feet tall at the shoulders and weighed around fourteen hundred pounds. The bear was a formidable carnivore, but it was not alone as it stalked the herbivorous browsers of savanna, swamp, and woodland. The bear’s competition included saber-toothed cats, jaguars, lions, and packs of dire wolves.

These predators fed upon wildlife much different than that of present-day Missouri animals. During the ice age there were also tapirs, armadillos, camels, and crocodiles living in the area that is now Missouri. These animals probably numbered in the millions, and most of them vanished, including the predators, in a relatively short span of time. The issue of why they disappeared so quickly toward the end of the ice age is a subject of considerable scientific debate.

Throughout geologic history there have been many ice ages. The most recent one began about two million years ago. Its cause, like the extinctions of plants and animals, is still highly debatable. Why some animals grew so large during the ice age is also uncertain, but it may have had to do with the nutritional value of the vegetation they consumed and the abundance of good things to eat. Their large size may have also been an adaptation to challenges in the overall environment.

The extinction of these animals may have been caused by the changing climate, but mass extinctions are nothing new. They have occurred a number of times over the past six hundred million years. But while the older extinctions were probably due entirely to natural events unrelated to humans, it appears that some of the extinctions in Missouri did not occur until after the arrival of Native American (Paleo-Indian) groups around ten thousand to fourteen thousand years ago.

Missourians began asking questions about these fossils in the nineteenth century, when the remains kept turning up in newly plowed fields, creek gravel, river sediments, clay banks, and at construction sites. Some of the first bones of mastodon, peccary, and ground sloth were excavated in the 1830s in eastern Missouri around Kimmswick.

Today, however, most ice age animal remains are found in caves. Animals such as mammoths and mastodons certainly did not live in caves, but their bones were often washed into caves by storm waters or their carcasses dragged into caves by predators. Sinkhole pits that dropped into caves also served as animal traps. The animals would fall in, be unable to climb out, and die of injuries or starvation. Dire wolves, bears, cats, and a few other animals probably denned in caves and dragged their prey into caves, thus leaving behind a stash of bones for today’s cavers to find and paleontologists to study.

One of the most surprising such cave discoveries occurred September 11, 2001, at Springfield, Missouri. On the very day that terrorists were destroying the World Trade Center towers in New York City, a road construction crew discovered a remarkable cave beneath the city streets of Springfield, the largest city in the Missouri Ozarks. Known today as River Bluff Cave, this unique resource contains more than a half mile of passage and is highly decorated with cave formations. It also contains a vast accumulation of ice age animal remains and footprints. Scientists now consider the cave a world-class fossil site, and it may be the oldest fossil cave in North America. This time capsule of the ice age had been sealed by natural events for thousands of years, protecting its fossil remains, which some scientists estimate to be six hundred thousand to one million years old.

The giant short-faced cave bear denned in River Bluff Cave, leaving behind its beds and mighty claw marks as well as a tale of slaughter when it preyed on flat-headed peccaries. The peccaries left behind a rare trail of footprints, bones, and feces in the cave. Even the waste matter of these ancient animals is important because it can tell us what they ate, facts about their environment, and the general nature of their health.

Fossil remains from the cave include mammoth, horse, musk ox, turtles, snakes, and the saber-toothed cat. Since this ice age “museum” has only recently been discovered, its resources have barely been researched. Who knows what discoveries are yet to be made in River Bluff Cave?

Giant cave bears and ice age cats were the first mammals to use caves in the Missouri Ozarks as dens, but mankind too would find refuge in the caves beginning around eleven thousand years ago. Prehistoric cultures would leave behind ceremonial sites, footprints, artwork, fabrics, stone and bone tools and weapons, the remains of countless meals, and even evidence of human burials in Missouri caves.