2

Prehistoric Times

If “Cave Man”. . . ever existed in the Mississippi Valley, he would not find any part of its natural features better adapted for his requirements than in the Ozark hills.

—GERARD FOWKE, Cave Explorations in the Ozark Regions of Central Missouri, 1922

Because Missouri is at the confluence of the nation’s three great heartland rivers, the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio, it became a crossroads for America’s prehistoric Indian cultures. Scientists estimate that the total number of archaeological sites in Missouri could be in the millions. For some counties alone, there are more than two thousand recorded sites, according to Missouri archaeologist Larry Grantham.

Water, to a large extent, determined where prehistoric groups settled or had temporary campsites. It had a major impact upon their environment, their food, and their physical prosperity. These factors, in turn, influenced their social structure, material culture, religion, and trade patterns. Prehistoric Indians, like the American and European settlers who came after them, tended to live along rivers and close to freshwater spring outlets. Missouri caves and rock shelters are most frequently found in bluffs, in sinkhole basins, and along hillsides of streams and rivers. Spring outlets, regardless of their size, are simply cave openings that discharge groundwater.

By definition, a cave generally has an opening that is deeper than it is wide and penetrates the hill, whereas a rock shelter is a hollow that is generally wider than it is deep without a cave component. There are exceptions since both characteristics can be part of the same natural feature or closely associated with it. There are many rock shelter archaeological sites throughout Missouri and many of them have produced prehistoric materials. The number of cave sites that contain prehistoric material is definitely fewer in number. Yet some cave sites are highly significant because cave environments often preserve materials for a long period of time. This depends, of course, upon the composition of the prehistoric material. Good examples are the finds at Arnold Research Cave, also known as Saltpeter Cave, in Callaway County.

John Phillips, one of the first settlers of Callaway County, settled near the present town of Portland and took possession of this cave in 1816 for the purpose of making gunpowder from the cave’s saltpeter deposits. The cave subsequently became known as Saltpeter Cave. Some years later, H. E. Arnold came into possession of the Saltpeter Cave property, and by the early twentieth century the cave was known as Arnold Cave. Long noted for the beauty of its entrance, which has a graceful arch of sandstone spanning two hundred feet, the entry chamber leads to several additional rooms within the hill that are connected by low-ceiling crawlways.

Professional archaeological excavation began at the cave in the mid-1950s. Since then it has been called Arnold Research Cave. The excavations resulted in the discovery of prehistoric materials dating back seven thousand to ten thousand years. Among the finds were more than thirty specimens of perfectly preserved moccasins and slip-on shoes estimated to be nine thousand years old. The moccasins were made of leather while the other shoe-types were woven from fibrous plants. Such finds are uncommon, because most archaeological sites yield only prehistoric materials made of stone and bone. The dry, dusty condition of the cave deposits containing the preservative elements of saltpeter may have been partially responsible for the excellent state of preservation of the shoes.

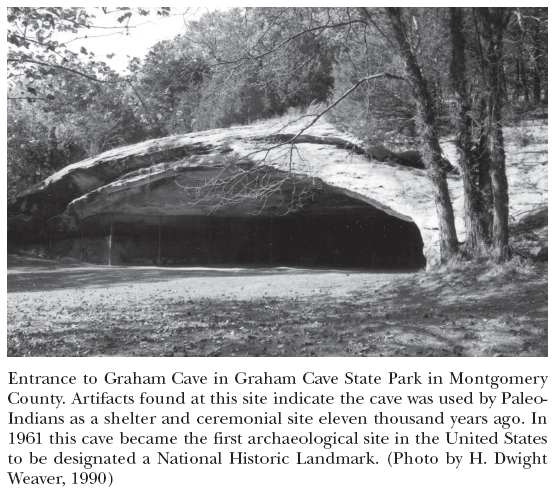

Not far away, in adjacent Montgomery County, is Graham Cave, which was formed in the same St. Peter Sandstone formation as Arnold Research Cave. Graham Cave, however, does not have internal chambers and is more easily classified as a rock shelter. It is now the centerpiece of Graham Cave State Park. Artifacts found in the shelter cave are as much as ten thousand years old, according to radiocarbon dating technology.

Archaeologists have divided the span of time between the appearance of the first Indians in Missouri and the arrival of European settlers into periods that reflect major cultural advances among these vanished people. They include the hunters of the Paleo-Indian Period, 12,000–8000 BC; the hunter-foragers of the Dalton Period, 8000–7000 BC; the foragers of the Archaic Period, 7000–1000 BC; the prairie-forest potters of the Woodland periods, 1000 BC–AD 900; and the village farmers of the Mississippian periods, AD 900–1700.

Most of these cultures used caves from time to time as campsites, as refuges from winter cold and summer heat, as a source for flint to make weapons and tools, and as a source of water, clay for pottery, and minerals that had ceremonial and medicinal uses. Native Americans left pictographs (prehistoric drawings or paintings) and petroglyphs (prehistoric carvings and inscriptions) on some Missouri cave walls. According to Carol Diaz-Granados and James R. Duncan, in The Petroglyphs and Pictographs of Missouri, about one-third of Missouri’s known rock-art sites are “located on the inner or outer walls of caves and rock shelters.”

Very few people think of Missouri caves as graveyards, but some caves contain Indian burials. Such burials are of special interest to professional archaeologists and their associates in their pursuit of the secrets of Missouri’s prehistoric past. Unfortunately, the burials are also of interest to unethical collectors who seek Indian artifacts and grave goods for profit. Professional archaeologists have a word they use to describe unprincipled, profit-motivated artifact collectors—looters. These grave robbers seldom keep records of their finds and make no effort to report their discoveries.

No one knows for certain just how many of Missouri’s current 6,200 recorded caves contain Indian burials. In order to protect the cave resources from looters, no list of such caves has been made public. But it is safe to assume that scores of Missouri caves have yielded Indian remains over the past two hundred years.

Early European and American settlers who mined Missouri caves for saltpeter were probably the first to happen upon prehistoric burial sites, because they had reason to excavate cave soils. From the beginning of European settlement, it was “open season” on Indian artifacts and graves. The collecting of antiquities, as Indian artifacts were then commonly called, evolved into a popular pastime. Digging in caves to find artifacts and burials became a popular activity, and the market for antiquities blossomed. The average antiquities collector in the late 1800s and early 1900s felt no regret about plundering artifact sites and taking Native American grave goods and body parts because of their belief that the Indians were uncivilized and racially inferior to whites.

Unfortunately, elements of this attitude have survived to the present day, because Indian artifact and burial sites in Missouri caves are still the focus of looters, who often do their digging at night or with posted lookouts during the daytime. They operate in the Ozark hills in much the same fashion as moonshiners once did and methamphetamine manufacturers do today, creating a dangerous situation for anyone who might happen upon them unexpectedly.

Digging up Indian artifact and burial sites on federal or Indian tribal land without proper authority is in violation of federal law, in particular the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation of Cultural Patrimony Act (November 1990). Even digging up unmarked graves on private land or in caves in Missouri without the proper authority is a violation of Missouri law. Missouri law defines such burials as “any instance where human skeletal remains are discovered or are believed to exist, but for which there exists no written historical documentation or grave markers.” If you knowingly disturb, destroy, or damage an unmarked human burial site, you are committing a class D felony, which can result in imprisonment and a fine.

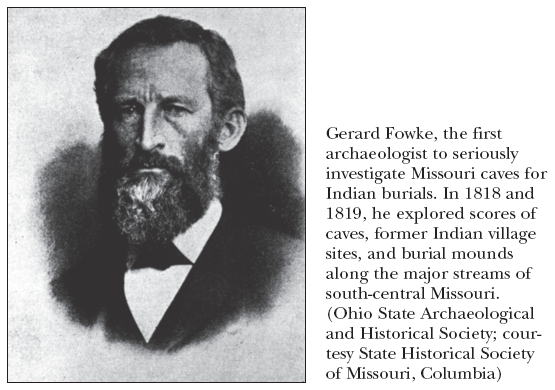

Archaeologist Gerard Fowke, a tall, stern, independent man of frugal habits and eccentric behavior, was the first scientist to seriously investigate Missouri caves for Indian burials. In 1918 and 1919, he explored scores of caves, former Indian village sites, and burial mounds along the major streams of south-central Missouri. He was searching for evidence to support a theory that the ancestors of Native American cultures migrated to the United States from Asia.

The caves Fowke examined were largely along the banks of the Gasconade and Osage rivers and their tributaries. His report was published in 1922 in Bulletin 76 of the Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. It is interesting to read because of his social commentary, recording folklore as well as fact. He found many human bones and skulls in the caves he excavated, although antiquities collectors and curious local people had excavated in some of the caves long before Fowke’s arrival. When he examined Ramsey’s Cave along the Big Piney River, he recorded a story about a naive local man who had a joke played on him while digging for artifacts in a cave. The story illustrates the attitudes of many of our ancestors toward Indian remains versus the remains of white people.

“A man living near the cave reported that a few years ago he was digging in a narrow space between the east wall and a large fallen rock,” said Fowke. “He came upon the feet of two skeletons and took out the lower leg bones. Being assured by a friend that these were not bones of Indians because they were not ‘red,’ and so must be the remains of white people, he replaced them and threw the earth back on them.”

Both archaeologists and looters are concerned primarily with Indians who placed their dead in caves. But in the 1800s, after the arrival of Americans and Europeans, bodies of several white people also wound up in caves through some spooky and bizarre happenings.