4

Saltpeter and Gunpowder

In the spring of 1810, James McDonald, of Bonhomme, and his two sons went to some caves on the Gasconade River to make saltpeter, and in three weeks returned to St. Louis with 3,000 pounds.

—WILLIAM CLARK BRECKENRIDGE, Missouri Historical Review, October 1925

Historians have long thought that Hernando de Soto, who died in Arkansas in 1542 during his famous sixteenth-century expedition into North America, did not reach present-day Missouri. But in 1993, a commission of prominent de Soto scholars released newly translated, controversial, four-hundred-year-old Spanish accounts that said otherwise.

According to Donald E. Sheppard, one of the scholars who traced de Soto’s Missouri route, the de Soto expedition found salt (sodium chloride) at Saline Creek, near St. Mary’s in the southeast corner of Ste. Genevieve County. They first found saltpeter (potassium nitrate) near Pilot Knob (west of Ironton), and then again near the White River in the Branson neighborhood while they were traveling toward Arkansas. The area they passed through between Forsyth and today’s Arkansas border is a cavernous region. In what cave they found saltpeter is presently uncertain, but it may have been Bear Den Cave not far from Reed’s Spring. A saltpeter mining operation functioned at this cave as early as 1835, supplying material for one of the first powder mills in southwest Missouri.

The conquistadors’ discovery of saltpeter in Missouri is of historic importance. The Missouri sites were the only places, according to Sheppard, where Hernando de Soto’s people found saltpeter in North America. In the years that followed, saltpeter miners became the first Europeans to place a memorable stamp upon the history of Missouri caves. In Missouri, the two backwoods operations—saltpeter mining and gunpowder making—generally went hand in hand and often took place on the same property. It was a dangerous process, and in pioneer times many powder mills exploded and people were killed because their methods and tools were crude.

Missouri public records show that “Jack Maupin had a powder plant on the Meramec River in a cave and supplied trappers with most of their munitions. Fisher’s Cave, Saltpeter Cave [Meramec Caverns], and Copper Hollow Cave, all . . . near Sullivan, were famous powder making plants from 1810 to 1820.” Apparently another member of the Maupin family had a powder plant near Dundee in Franklin County, but according to an early historian, his plant exploded.

Saltpeter, also known as niter, is potassium (or sodium) nitrate. When it is combined and ground together with charcoal and sulfur, correctly and in just the right quantities, it produces black gunpowder. The making of gunpowder in Missouri in pioneer times relied largely on the mining of saltpeter earth (“peter dirt”) from caves, and the process for making it was common knowledge at that time.

Not all cave soils contain saltpeter, and how the soils of some caves become charged with this substance has long been a mystery. Even today scientists are not entirely certain about the origin of saltpeter in caves. Various theories explain its origin; one explanation is that groundwater seepage brings nitrates into the cave from surface soils. Another theory suggests that species of bacteria and other microorganisms enrich the cave with nitrates. Still another explanation points to the waste matter of bats and rodents, which is high in nitrates; since certain species of both animals use Missouri caves as a habitat, their waste deposits can enrich the cave soil.

Saltpeter miners often placed the peter dirt in triangular wooden vats or hoppers, then poured water on top of the dirt. As the water seeped down through the dirt, it collected (leached) nitrates. The nitrate-rich water dripped into a trough at the bottom of the hopper, which drained into a large kettle. This liquid was then heated, and the water boiled away, leaving small, white, needlelike crystals of saltpeter in the bottom of the kettles. The crystals were then used to make gunpowder. Saltpeter crystals have a cool, bitter taste and will flash if tossed into a fire.

Missouri has nineteen caves called “Saltpeter Cave” and several more with the word saltpeter in the cave’s name. Counties that have one cave each by the name Saltpeter include Callaway, Crawford, Dallas, Douglas, Franklin, Laclede, Madison, McDonald, Phelps, Shannon, Ste. Genevieve, Stone, and Texas. Dent County has two caves called Saltpeter, and Pulaski County has four. Having the word saltpeter in its name does not mean that a cave was mined for saltpeter, yet it probably does mean that at some early date saltpeter deposits were recognized in the cave.

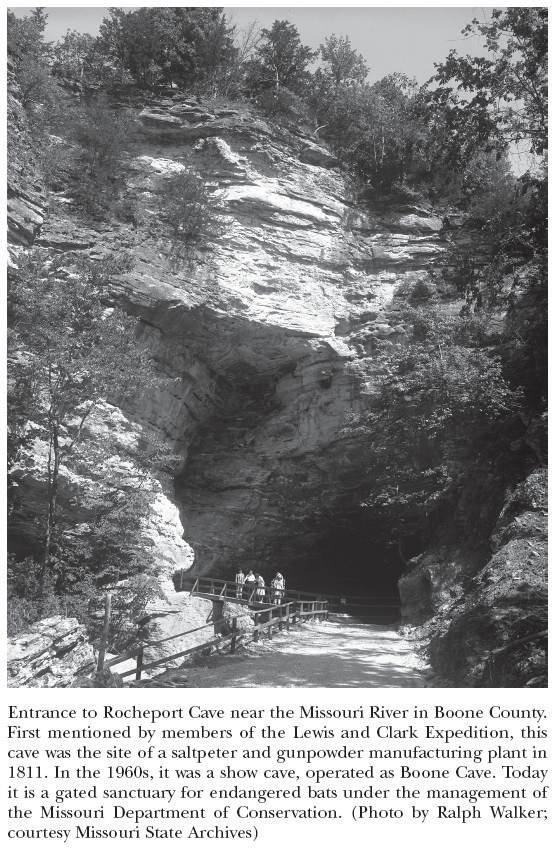

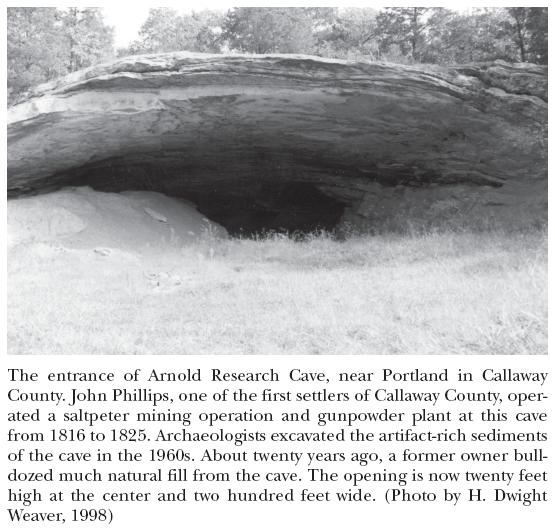

“Saltpeter” is a nineteenth-century name for a cave. Because early Missouri settlers needed saltpeter and searched caves for it between 1720 and 1820, caves in which it was found often became locally known by the name. Some caves in Missouri that were once called “Saltpeter Cave” have since been given another name. These caves include Ashley’s Cave in Dent County; Boiling Spring Cave in Pulaski County; Indian Cave in Franklin County; Arnold Research Cave in Callaway County; Temple of Wisdom Cave in Crawford County; Fisher Cave, Copper Hollow Cave, and Meramec Caverns in Franklin County; Friede’s Cave in Phelps County; Bear Den Cave in Stone County; Rocheport Cave in Boone County; Mark Twain Cave in Marion County; Marsh Creek Cave No. 1 in Madison County; and Firey Forks Cave in Camden County.

Unfortunately, records of saltpeter mining are very scarce because most backwoods operators never made an official report of their activities. There are probably many additional caves in Missouri that were mined for saltpeter but have escaped the notice of historians. One might suppose that the War of 1812 and the Civil War stimulated considerable saltpeter mining and gunpowder making in Missouri caves, but there is very little evidence to indicate that such was the case. Carol A. Hill, an authority on saltpeter mining in North American caves, states that Missouri was not an important producer of gunpowder during either war.

Saltpeter mining in caves in the Appalachian Mountains began at Clark’s Saltpeter Cave in Virginia about 1740. It probably began in Missouri shortly after 1720, initiated by Philip Renault, who established himself at Kaskaskia, Illinois, in that year and began mining lead in Missouri west of Ste. Genevieve. “It is probable that from the year 1720 when Renault and La Motte opened and worked the lead mines in this region on a large scale and roasted the ores therefrom to eliminate the sulphur that they, as well as those who came after them . . . made their own gunpowder, using the waste product sulphur in its manufacture,” wrote William Breckenridge in a 1925 issue of the Missouri Historical Review.

Folklore of the area credits Renault with the discovery of Meramec Caverns, originally known as Saltpeter Cave, today a show cave near Stanton. “Saltpeter Cave is a large opening below Fisher’s Cave. It is entered from near the river. . . . Gunpowder was made in this cave at an early date,” according to an early Franklin County historian.

The powder mill operation headquartered at Meramec Caverns and operated by Renault existed between 1720 and 1760. The plant, however, may not have been in continuous operation during all four decades. The operation involved a network of caves producing saltpeter along the Meramec River. The labor force probably consisted of black slaves. It was quite possibly the most productive powder mill to operate in Missouri between 1720 and 1820. Since no production figures are available for the Meramec Caverns powder mill, how it ranks against the better-known powder mill established by William H. Ashley in a Dent County cave in 1814 is unknown.

William Henry Ashley, born in Virginia about 1778, was a fur trader, miner, politician, and frontier entrepreneur. He came to Missouri in 1802, applied himself to various enterprises, got into financial trouble, and then became a lieutenant colonel during the War of 1812. On one of his hunting trips in the Ozarks during the war, he happened upon a large cave in Dent County and discovered that it contained ample deposits of saltpeter dirt. He thought that by establishing a powder plant and saltpeter works, he could make enough money to solve his financial problems.

Colonel Ashley went into partnership with General Benjamin Howard, a fellow military man in the territory, and they began mining saltpeter at the big cave, which subsequently became known as Ashley’s Cave. It was operated in conjunction with Ashley’s powder mill at Potosi. At the start, production was about three thousand pounds per year, worth about twenty thousand dollars, but the saltpeter deposits at Ashley’s Cave were extremely sensitive and given to unexpected and deadly flash explosions. The factory at the cave was destroyed three times by explosions, and on one occasion a wagon carrying saltpeter exploded and killed several men. By 1818, the market for gunpowder had fallen on hard times and the cave powder mill operation was abandoned. After giving up his powder mills, Ashley had much better financial success when he established the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, which was associated with such early American explorers as Jedediah Smith, William Sublette, and Jim Bridger, members of “Ashley’s Hundred,” young men who answered his call to go west to make their fortunes.

Well into the twentieth century, Ashley’s Cave continued to have problems. In April 1930, the Crane Chronicle newspaper reported that “a brand of fire” had probably struck the entrance of Ashley’s Cave, causing an explosion and fire. “But it was only another peculiar and unexplained incident in connection with this century old powder plant,” the paper reported. The ground at the cave, according to the article, is still heavily charged with saltpeter, charcoal, and sulphur, which might be ignited by a dart of lightning.

A caver, hunter, or hiker who might happen upon an Ozark cave once mined for saltpeter would be wise not to light a match or start a fire in the cave or take shelter in the cave entrance during a storm that produces lightning. This would be especially true at Ashley’s Cave, which has three entrances.

Nevertheless, according to folklore, hunters have used Ashley’s Cave since settlement days as a campsite and refuge against unexpected storms. In the early 1800s, many hunting parties were in pursuit of bear, and some hunters may have probed Ashley’s Cave for wild game. Bear hunting in Ozark caves was a popular pastime in the first half of the nineteenth century.