5

Bear Hunting

From a cavern in Boone County . . . skeleton material representing a dozen or more individual bears of this species [Ursus americanus] has been collected by Professor Elder of the University of Missouri.

—M. G. MEHL, Missouri’s Ice Age Animals, 1962

Before the arrival of American and European settlers, black bears were common throughout Missouri, particularly in the Ozark region. The bears were becoming rare in the woodlands by the 1850s and were gone from most of the state by the 1880s, victims of habitat loss and overhunting. Their demise left behind a strong body of folklore and a host of place-names. Robert L. Ramsay, in Our Storehouse of Missouri Place Names (1952), says there are more than five hundred localities within the state that derive their names from eight of the larger game animals, and prominent among these is the bear.

Indeed, the Great Seal of Missouri carries the image of bears. More than 127 places in Missouri have been named for the bears. These places include branches, creeks, hollows, springs, ridges, cemeteries, schools, quarries, townships, mountains, sloughs, and caves. In fact, forty-three caves in Missouri have the word bear as the first word in their names. No other geographic feature in the state makes a greater use of the word. Among these are the names Bear Cave (the most common), Bear Bed Cave, Bear Cave System, Bear Creek Cave, Bear Den Cave, Bear Hole Cave, Bear Hollow Cave, Bear Mountain Cave, Bear Tooth Cave, Bear Track Cave, Bear Waller Cave, and Bear Claw Cave. Some of the names are associated with more than one cave, and the caves are scattered across twenty-three counties, most of them in the southern half of the state. Shannon County, with eleven “bear” caves, has the most, followed by Ozark County with four, and Taney, Crawford, and Camden counties with three each.

Because bears became extinct in Missouri by 1890, the word bear generally indicates that the cave was named before that date. Many of these names probably originated when bears were seen in the vicinity of the caves or were found wintering in them.

Bear hunting was considered great sport in the Ozarks in the early part of the 1800s. When Henry Rowe Schoolcraft made his historic trip through the wilderness of the Ozarks in 1818, he commented on the relationship between bears and the settlers he found along the way, particularly in the White River country. He found one settlement occupied by several families of primitive, backwoods hunters, who, he said, could only talk of bears, hunting, and the like.

Schoolcraft described how these hunters would track an animal to its den during the winter by following its tracks in the snow or by using dogs. If they found the bear in a cave, they would shoot him there or send in the dogs “to provoke him to battle; thus he is either brought in sight within the cave, or driven entirely out of it.” Schoolcraft noted that a shot through the heart was necessary because “a shot through the flank, thigh, shoulder, or even the neck does not kill him but provokes him to the utmost rage, and sometimes four or five shots are necessary to kill him.”

Occasionally the bear hunters met with accident, such as the one that, according to folklore, befell Sylvestre Labaddie Sr. in a Franklin County cave that has ever since carried his name. As the story goes, Labaddie and his son Sylvestre Labaddie Jr. followed a wounded bear to the cave. Labaddie Sr. crawled in, thinking that the bear’s wound was mortal. The son waited for hours. When his father did not return, he went back to St. Louis and summoned rescuers, but they were unable to relocate the cave. Some years later, according to legend, the skeletons of the hunter and the bear were found in Labaddie Cave. Some historians take issue with this story because records show that Sylvestre Labaddie Sr. died in St. Louis in 1794 of natural causes.

Nearly forty years after this supposed bear-hunting accident, The Youth’s Literary Gazette (1833) published a bear story about a Frenchman and his son that may be the origin of the Labaddie legend. According to this account, after the hunter crawled into the cave, he shot the wounded bear again. The bear, in its attempt to escape, tried to crawl out of the cave and became stuck in the small entrance. There the bear died, trapping the hunter inside the cave. Because there were no roads in the area and the hunter’s son had not observed the landmarks well, he could not guide rescuers back to the cave. His father subsequently died in the cave, unable to get past the bear’s carcass.

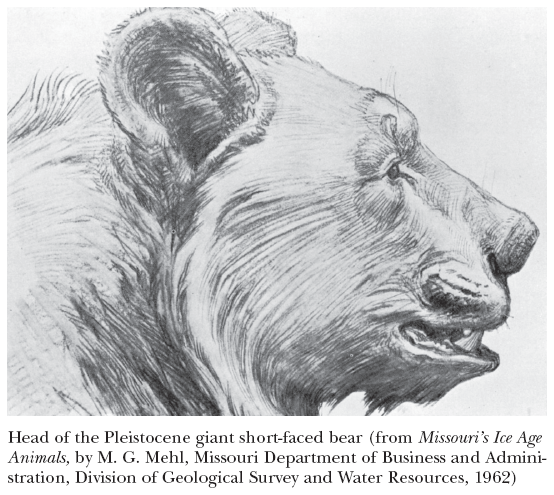

Because hunting wintering bears in Ozark caves was such a popular sport in the early days of exploration and settlement, folklore would have us believe that just about every cave in the Ozarks was first discovered by bear hunters and their dogs. The oldest records of bear in Missouri caves are those of the giant, short-faced cave bear (genus Arctotherium) that inhabited the Ozarks during the ice age. But most bear specimens unearthed in Missouri caves are those of the common black bear (Ursus americanus). So many remains have been found that it is obvious these bears routinely wintered in the caves and often in groups.

The absence of bears in Missouri woodlands after 1890 made them popular attractions at city zoos in the decades that followed. But a zoo established in Meramec State Park south of St. Louis near Sullivan in the 1930s came very close to reintroducing bears in the woodlands along the Meramec River in Franklin County.

The 6,800-acre park was established in 1928. Caves and springs are among the park’s most outstanding features. In 1930, Sheep Cave became a holding pen for bears, foxes, and raccoons. By the summer of 1933, it had been renamed Bear Den Cave and converted exclusively into a bear den. “Four Missouri black bears are kept there now” the local newspaper reported. Mating in captivity, one bear gave birth to cubs in 1936. The park attendants were elated, and the local paper reported the event in detail.

The late Eddie Miller, who for many decades was the general manager of Bridal Cave at the Lake of the Ozarks, grew up in Franklin County. He was born at Sullivan in 1911 and raised on a farm just outside the boundaries of Meramec State Park. In 1936, he worked at the park taking care of boat rentals, the bathing beach, and other concession duties. He became personally acquainted with the bears. In 1937, Eddie assumed responsibility for Fisher Cave, the park’s show cave operation. Like any good cave entrepreneur, he was always looking for new ways to entertain his visitors. He soon discovered a way to use the bears on his cave tours. In 1975, Eddie told the author about his experiences with Fisher Cave and the park bears.

According to Eddie, the park had two bear cubs that broke out of the zoo and couldn’t be found. That winter they hibernated in some cave in the park and showed up the next spring nearly full-grown. The bears got into a fight and one killed the other. “He was loose for a long time,” said Eddie. “He must have been about three years old when I got acquainted with him. He would raid the garbage cans in the park.”

One day when the Fisher Cave gate was open, Eddie saw the bear go into the cave, so he locked him in overnight. “I figured he’d make a lot of tracks in the cave and it would be a good attraction,” Eddie said. “I don’t think the park superintendent ever knew about it. But I had beautiful bear tracks all over the place.”

On another occasion when Eddie locked the bear in the cave overnight, he had an early-morning tour the next day of about a dozen people, and they encountered the bear, unexpectedly, underground. The tour group had no idea there was actually a live bear in the cave. Eddie had told them, but they thought he was joking. “I caught a glimpse of that bear going around a corner just ahead of us,” Eddie said. Fisher Cave is not electrically lighted. It is shown using hand-held lanterns, which made seeing the bear difficult.

The bear stayed just out of sight until the tour group reached a place where the cave passage narrows and the ceiling lowers. That’s when the bear turned around. “Here he came,” said Eddie, “right down the passageway, just a-snorting and rearing. He thought he was getting trapped or pinned down, and he was mad. He was a grown bear, and I figured we’d better let him have his way: ‘Give him room!’ I shouted. ‘Give him room!’

“The people were scared to death. There was one woman who just froze, right in the bear’s way. She was so scared she wet all over herself. She just couldn’t move, so I jumped over and grabbed her by the arm and jerked her out of the bear’s way and off the walk. That bear came right on and just shot right past us. That was the last time I ever locked a bear in Fisher Cave overnight.”

Now, nearly seventy years later, we have bears once again in Missouri, but not from Meramec State Park’s failed attempt to keep bears in a zoo. The bears have migrated north from the Arkansas portion of the Ozarks into southern Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation officials believe we now have about three hundred bears living in some forty-nine counties. They have presented no problems and are protected by law.

During early settlement, once homesteaders determined that there were no bears in a cave on their property, they often began using caves for a variety of farm and home needs, such as a springhouse or a barn.