6

Farm and Home

During early settlement and development of the Ozarks . . . springs were used as domestic and stock water supplies; many springs also became the sites of grist mills, which were the hub of many community activities.

—JERRY D. VINEYARD AND GERALD L. FEDER, Springs of Missouri, 1982

Caves often served as springhouses to store food for Ozark dwellers. Even though rural electrification came to Missouri in the 1930s and 1940s, there were many areas in the Ozarks where homes and farms did not receive electrical service until the early 1950s.

Many Ozarkers continued to use spring- and cave-water supply systems even after the arrival of electricity, drilled wells, and submersible pumps, because the old cave systems could be used to water livestock. But the springhouse was a necessity in the days before electricity and artificial refrigeration were available. Meats were generally dried or salted and smoked. Vegetables and fruits could be dried, pickled, or canned. But milk, cheese, and butter had to be kept cool, and the springhouse provided a means of refrigeration that greatly extended the life of such perishable foods because caves and springs in the Ozarks have a year-round temperature of 56–60 degrees.

There are thousands of springs in the Ozarks. By the time electricity came to the Ozarks, there were also thousands of springhouses scattered through the hills and hollows. Since many of them were built of stone, brick, or concrete, it is still possible to find these abandoned relics of the past, although they are becoming scarce. Springhouses were either built over the spring outlet or over the spring branch so that the cold water would flow through a rock or concrete trough inside the springhouse. Water entered on one side of the building and exited on the other. Milk and butter in cans or jars would be set in the water that flowed in the trough. Shelves around the sides of the springhouse provided storage for other food items. The water inlet and outlet would be screened to keep animals out of the building.

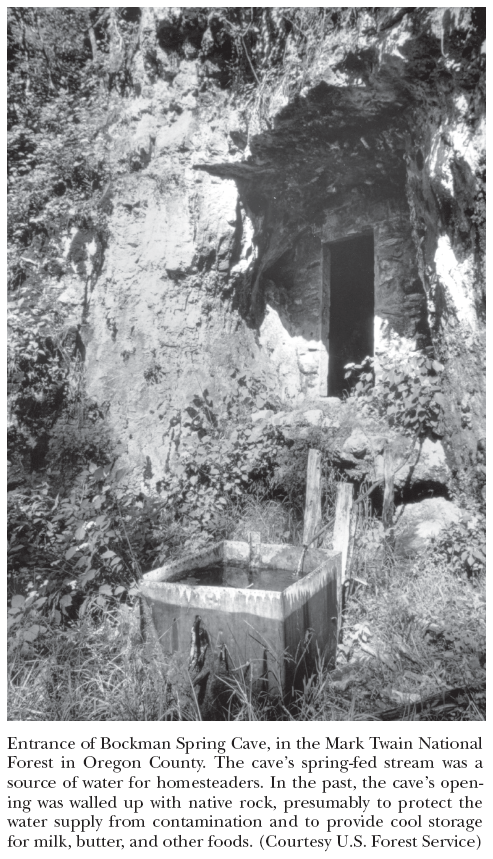

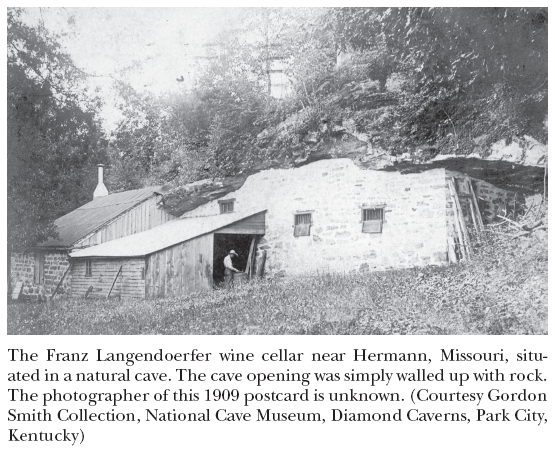

When a cave was available, it was often used as a springhouse if the cave entrance was not too large and could be walled up to keep animals out. Dams were also built inside many caves (or at the entrance) to impound the flow of a spring-fed cave stream. However, not all cave streams are fed by perennial springs, and some flow only during (or for a short time after) a rainfall. Caves were still being converted into springhouses and domestic water supplies as late as the 1950s. The entrance of Leech Spring Cave in Oregon County has a small dam across it with a pipe and the initials LMC, which stand for Lloyd M. Cooper, and the date 1955 is etched into the concrete. McDowell Cave, in the same county, was once used as a fruit cellar. In 1981 it still had a low stone wall, flagstones, and the remains of a garden and other ruins. Inside the entrance of McDowell Cave, in the concrete among the flagstones, was etched “May 23, 1941, Utah McDowell, Wilderness, Missouri.”

More than two hundred caves in the Ozarks still bear evidence that they were once used for such purposes as food storage. Such evidence consists of crumbling dams, walled-up entrances with doorways, pipes, concrete- and rock-walled troughs, dilapidated shelving, platforms, and old water tanks and abandoned hydraulic rams. There are even a few Ozark caves with interior dams and reservoirs that are still providing water for livestock.

Taney County has nineteen caves with surviving ruins that attest to their use for water supply and cool storage. Oregon County has sixteen such caves, Pulaski County fifteen, Christian County fourteen, Camden and Greene counties thirteen each, and Jefferson County twelve. Counties with anywhere from two to eight caves with springhouse and water supply ruins include Barry, Boone, Crawford, Dent, Jasper, McDonald, Miller, Morgan, Ozark, Perry, Phelps, Ralls, Shannon, Ste. Genevieve, St. Louis, Stone, Webster, Wright, and Texas. There are an additional twelve counties that have one cave each with such evidence.

Ozark caves have also been used as barns for cattle, sheep, goats, and swine. In the 1930s, an eccentric goat herder used a cave in southwestern Missouri as a shelter for both himself and his goats, thus inspiring the name Goat Man Cave.

Pulaski County has six caves that were once used as barns, St. Clair County has four, Phelps County has three, and Iron, Laclede, McDonald, Miller, Ste. Genevieve, and Stone counties have one cave each that served as a barn. Hayes Cave in Stone County has been a natural barn since 1860. In the 1840s, the cave provided a home for the homesteading Prichard family from Tennessee. Subsequent owners of the property used the cave as a barn for more than a hundred years.

Experimental farming has also occurred in some Ozark caves with attempts at raising celery and rhubarb. Many caves have been used to store watermelons and potatoes. There are eight caves in the Missouri Ozarks named Potato Cave: Christian, Dade, Greene, Miller, Ozark, and Shannon counties have Potato caves. Greene and Webster counties each have a Potato Cellar Cave, and Miller County has a Potato Spring Cave. Eight Missouri caves are named Sweet Potato Cave. Douglas County has three such caves, Texas County has two, and Barry, Miller, and Pulaski counties have one Sweet Potato Cave each. Vernon County has Tater House Cave.

Apples were once commonly stored in Ozark caves. Jacob’s Cave in Morgan County was used for apple storage in the 1920s and 1930s. A news item in the Eldon Advertiser on October 12, 1933, reported: “The Versailles Orchards Company, operators and owners of one of the largest apple orchards in the state located south of Versailles, are storing a portion of their crop in Jacob’s Cave. . . . About 1,500 bushel baskets have been placed in a part of the cavern and more will be put in later. The cave has a year ’round temperature of about 60 degrees and makes an ideal storage place for fruits.”

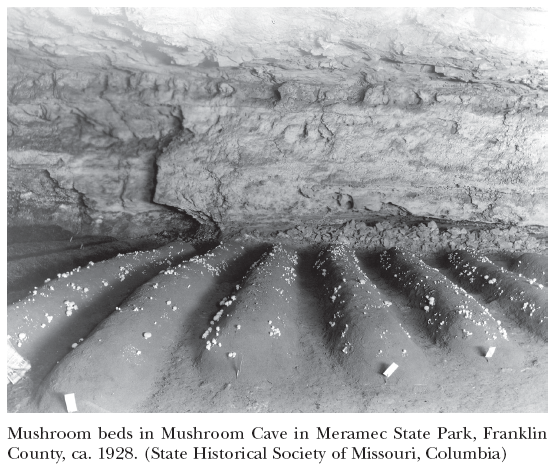

Although the food most often associated with underground farming in Missouri is mushrooms, only one cave in the Ozarks is named Mushroom Cave as a result of such commercial activity: Mushroom Cave, in Meramec State Park, in Franklin County. Mushroom Cave has three openings. Two openings are a thousand feet apart, but between them is a third opening that is considered the cave’s main entrance. Today the cave’s entrances are gated to protect an endangered bat colony. The cave has about fourteen hundred feet of spacious passage. In 1899, H. B. Kerriush of Sullivan raised mushrooms in the cave, leading to its name. His first attempt failed to show a profit, but he tried again between 1922 and 1927 with more success, shipping his product in fifty-pound lots to points as distant as Kansas City and Cincinnati, Ohio. When it was time to harvest the crop, trucks could be driven into the cave to the mushroom beds.

In the early 1900s, mushroom farming was carried out in both Crystal Cave and Sequiota Cave in Greene County near Springfield. During the 1930s, mushroom farming took place in Cameron Cave in Cave Hollow just south of Hannibal, and Poole Hollow Cave in Phelps County was the site of a mushroom-farming operation during the early years of the twentieth century. Poole Hollow Cave has an entrance seventy-five feet wide and twelve feet high. A masonry wall was constructed across the entrance to shut out daylight. The cave floor was smoothed out, and horizontal rows of mushroom beds were created for the edible fungi. Trucks reportedly backed into the cave for a distance of eighty yards to pick up the crop when it was harvested.

Mushroom farming in natural caves appears to have been plagued with problems, most associated with efforts to control the setting and protect the crop from fungus, diseases, and critters that like the cave environment. As late as the 1960s, however, people were still considering Ozark caves as sites for mushroom farms. In June 1966 the Missouri Division of Commerce and Industrial Development received a letter requesting information about Missouri caves suitable for such farming. The company requested a list of caves that had ceiling heights of ten feet or greater, at least two hundred feet of overburden (overburden is the amount of soil and rock between the ground surface and the roof of the cave), and a minimum of one hundred thousand square feet of floor space. The letter was referred to the Missouri Geological Survey, which provided an answer listing the square footage of fourteen caves that met the requirements. One of the caves on the list was Mushroom Cave in Meramec State Park. The reply also recommended the use of mines and underground quarries instead of caves, because mines have uniform ceiling heights, level or nearly level floors, and are easily accessible. In the Kansas City area, numerous abandoned underground quarries have been converted into very useful commercial and industrial sites.

Before and even after the arrival of electricity, more than one Ozark dweller came up with the clever idea of piping cave air into his home to provide air conditioning during the hot and sweltering days of summer. Show cave operators had the same idea and began building their gift shops, ticket offices, and administrative headquarters over or within the entrance of their caves. In the 1950s, one enterprising hog farmer in Boone County had the clever notion of piping cool cave air into his hog barns to keep the swine comfortable in summer and avoid the loss of many hogs to extreme heat.

As a means of air conditioning, the scheme of using cave air works, but there are downsides. A home or building cooled with cave air will soon take on the earthy, musty, basementlike smell of the cave. Cave air is humid, and mold can be a persistent problem. Filtering the cave air and using a dehumidifier can help, but most Ozarkers have given up the idea of air conditioning their home with cave air. Several Missouri show caves still air-condition their facilities with cave air, and one of the most successful is Meramec Caverns near Stanton.

These kinds of farm and home uses for Ozark caves have received little attention from historians and the media, but one use for the caves has been widely publicized in the past—their use as locations for moonshine stills during the days of prohibition.