7

Beer and Moonshine

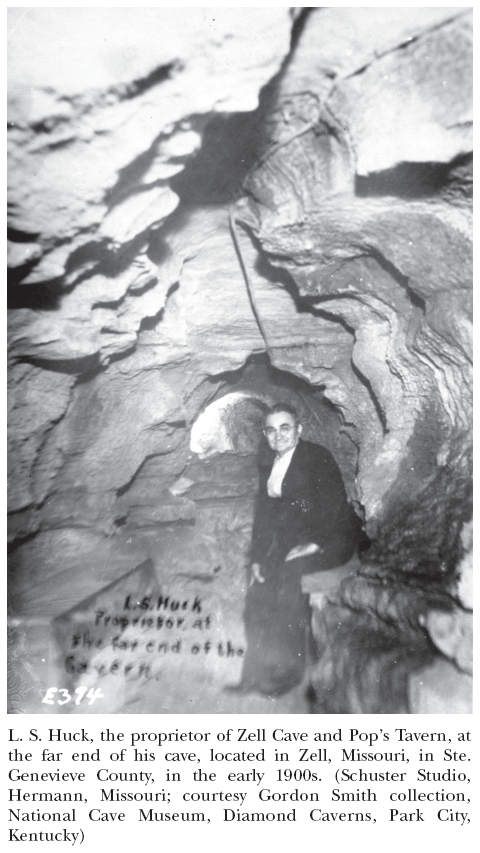

A long time ago . . . there was a little brewery in Zell [Zell Cave], and their product was aged down here. One night a hogshead sprang a leak. It was empty by morning, and all the beer had disappeared down cracks in the floor. About the middle of that forenoon, a German farmer in the valley below, came into town wildly excited. “Mein Gott, Mein Gott!” he cried, “mein schpring, she is running beer!”

—J HARLEN BRETZ, Caves of Missouri, 1956

Walter B. Stevens published a history of Missouri’s early taverns in 1921 in the Missouri Historical Review, reporting: “The oddest tavern in Missouri was not built with hands. It was a cave, forty feet wide and twenty feet high. . . . Boatmen steered their pirogues and longhorns to the bank and took shelter in that cave from the driving storms on the Missouri. They called it ‘The Tavern.’”

On May 14, 1804, Lewis and Clark paid a visit to this sandstone shelter cave along the banks of the Missouri River in Franklin County. The cave still exists, though access to it is difficult because of landowner restrictions. The river once lapped at its banks just below the cave but has since retreated some two hundred feet, leaving its flow to deposit enough silt and sand to create a substantial amount of land between the cave and the river. Today, the cave is almost invisible to boatmen, except in winter, because of the cottonwoods that have since grown up on this new landmass.

Above Tavern Rock Cave rises an impressive bluff three hundred feet high. Near the base of the bluff are railroad tracks that pass over the roof of the cave. In fact, when the railroad was built many decades ago, much rock was blasted from the bluff. Some of this waste rock now lies near the cave. It is fortunate that the railroad builders chose not to run the tracks at a lower level. Had they done so, this historic site might have been destroyed.

Captain Lewis recorded: “We passed a large cave on the Lbd. Side called by the French The Tavern—about 120 feet wide 40 feet deep and 20 feet high—many different images are painted on the rock at this place—the Inds. and French pay omage—Many names are wrote on the rock.”

Time and weathering of the sandstone has robbed us of these names and images because the interior of the cave is so exposed to the weather. Some recent visitors claim they can still see faint traces of some of the etchings, but the remaining marks are now impossible to interpret. Later explorers, including Zebulon Pike in 1806 and the German Prince Maximilian of Wied in 1833, visited Tavern Rock Cave. Maximilian was quite taken by this site as well as by other “tavern caves” that he learned about during his expedition. Rivers were the highways of travel and commerce in pioneer times. Boatmen, trappers, hunters, and others found riverside caves useful as temporary shelter. The caves were warm in the winter, were cool in the summer, and gave safe retreat from the mosquitoes that inhabited the marshes and sloughs along the river. More than one enterprising Frenchman set up business in these riverside caves, offering trade goods and services of comfort as well as strong drink. Other notable riverside “tavern caves” were found along the banks of the Gasconade and Osage rivers.

Beginning in the early 1820s, when settlers started to filter into southern Missouri and lay claim to fertile bottomlands and natural springs, the distilling of strong drink took place in caves all across the Ozarks. Many immigrants brought distilling skills, especially the settlers from the hills of Kentucky and Tennessee, where the distilling of whiskey had its inception between 1776 and 1793.

In colonial times beer was considered a food product and a healthful stimulant. Alcoholic beverages also had important medicinal and household uses. Men, women, children, and even people of most religious faiths were beer drinkers, and it was not widely considered a public, moral, or religious issue. Today, the drinking of alcoholic beverages is viewed largely as a recreational pursuit and is heavily regulated.

Throughout much of the Old World, there was a greater consumption of beer than water from the 1600s to the 1800s, because pure drinking water was so difficult to find in Europe. But when European and American settlers entered Missouri, they discovered the Ozark hills were watered by countless cold, pure, freshwater springs. It seemed almost too good to be true. Since a great many caves in the Ozarks produce spring-fed streams, springs and caves made ideal locations for the “family recipe.” The brewing and distilling of alcoholic beverages in those days was a cottage industry; more often than not, the family still produced only enough beer, wine, or liquor for its own use.

In settlement days, backwoods production of alcoholic beverages depended upon the season of the year, unless a way could be found to secure complete independence from outside temperature variations. So it was that Ozarkians turned to caves; caves were plentiful and maintained a nearly constant temperature every day of the year.

As time passed, the distilling of backwoods liquor spawned an industry because of the need for laborers, craftsmen, boatmen, teamsters, coopers (barrel makers), and farmers—all of them playing some role in the manufacturing, packaging, transportation, and selling of alcoholic beverages. As a consequence, men of greater ambition moved their distilling operations to locations with greater population densities and better transportation facilities. At this time, neither commercial nor private distillers were taxed or licensed by government agencies.

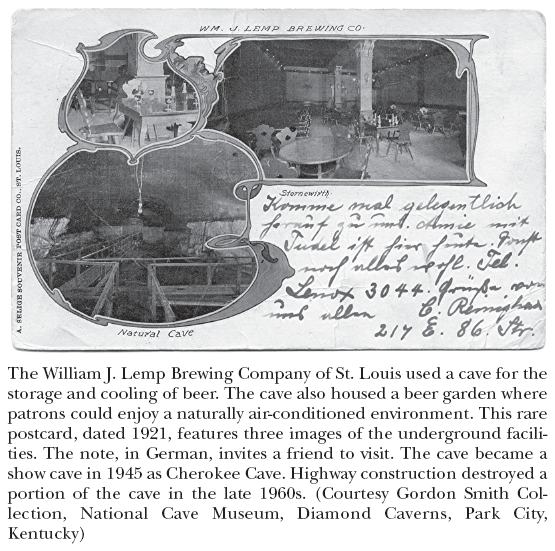

In the 1830s and 1840s, waves of German immigrants began to arrive in Missouri. The influx of German brewers during this period had a huge impact on Missouri culture, especially in the St. Louis area. The first beer in St. Louis was brewed as early as 1810 and sold for ten dollars a barrel. The tax records of 1811 indicate that in that year there was at least one distiller in the city. But by the 1840s, the city’s brewers included Stifel and Winkelmeyer, who founded the Union Brewery; the Washington Brewery, established by George Schneider; the Lemp Brewery, established by J. Adam Lemp; and the Joseph Uhrig Brewing Company, originally established by Joseph Uhrig and A. Kraut. Others came in the 1850s and 1860s.

What these breweries had in common, besides the production of Missouri’s first lager beers, were the caves they used for the cooling and storage of their product. The hills along the west side of the Mississippi River south of the mouth of the Missouri River in the St. Louis area are noted for the presence of sinkholes and caves. The band of topography containing these caves and sinkholes runs south from the city and follows the river all the way to Cape Girardeau. This strip of cavernous terrain is roughly 125 miles long by three miles wide and currently has more than one thousand known caves.

Within the city of St. Louis itself, there are twenty–nine known caves today; however, a great many more cave openings existed in settlement times. Growth of the city over the past two centuries has led to the destruction of many caves and sinkholes as they were filled in and paved over for the construction of buildings, roads, parking lots, and homes. Today, caves within the St. Louis area are largely ignored except in park settings. But from the 1840s to the 1890s, when no electricity was available, they were important resources, especially for brewers. The caves provided natural cooling in a controlled setting, which could be enhanced through modifications of the cave passages and the creation of ice storage chambers.

Some of the more extensive cave systems beneath the city exist only in segments, as long stretches of their passageways are naturally filled with clay, gravel, and other sediments. More than one brewery, some located many city blocks apart, used isolated segments of the same cave system. When necessary, the brewers excavated the sediments to enlarge their portion of the cave. The growth of the brewing industry in St. Louis, and the continued arrival of Germans, spread the industry both south and west of St. Louis. German breweries sprang up in other parts of the state, and some of them used natural caves as well as man-made underground cellars to cool and store their product.

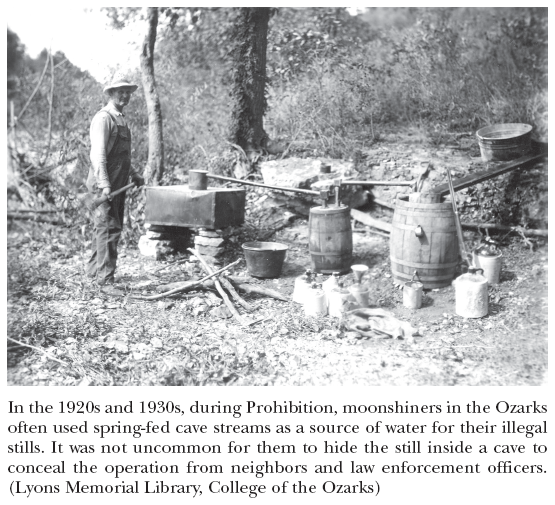

As the nineteenth century wore on, temperance movements arose to do battle with the brewers and the tavern, saloon, and nightclub proprietors who sold the beer. The federal government also began licensing and taxing the manufacturers and retailers of alcoholic beverages. In St. Louis, the legal breweries adapted to these problems with little trouble, but in the hills of the Ozarks, it was a different matter. Many Missouri Ozark natives, clannish, set in their ways, and resentful of any effort by the government to tax their whiskey or regulate their activities, made an even greater effort to hide their stills. Caves, of course, were perfect sites for secretive activities. It was at this time, in the 1880s, that the term moonshine came into use, because much of the whiskey making took place at night.

Government tax collectors were faced with a dangerous situation as they began to prowl the back roads and hills of the Ozarks. They followed spring-fed streams to their sources in an effort to locate caves where stills might be operating. They sniffed for the presence of smoke and mash. But they were in enemy territory where the tight-lipped population consisted of many intermarried families. And most Ozarkers went armed and were quite willing to defend their property against intrusion by government snoopers. The problem worsened as the tax kept rising. By 1894, the government was demanding a tax of $1.10 per gallon, which, by the standards of Ozark living, was considered outrageous.

And then the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which went into effect on January 16, 1920, brought nationwide prohibition and led to one of the most lawless periods in American history. The law criminalized the production and selling of alcoholic beverages. Although the rate of criminal activity in the state was the highest in St. Louis, out in the hills and hollows of the Ozarks, the stills went deeper underground and grew even more numerous following the stock market crash in 1929, which brought tough financial times even to the hill country. We have no way of knowing exactly how many or what caves in the Ozarks provided cover for moonshine stills, because the caves were often unnamed and the moonshiners did not keep records of their illegal activities. Missouri Supreme Court and circuit court case files, however, contain a wealth of information about this period of illegal moonshining in the Ozark hills, and Ozark folklore is riddled with moonshine stories.

Records of the Missouri Speleological Survey list more than forty caves scattered across twenty-three Missouri counties that have a surviving story or some physical evidence associated with legal brewing or illegal moonshine activities. Excluding St. Louis County and the City of St. Louis, most of these counties are in the Ozark region. Christian County has five such caves. Barry, Perry, and Shannon counties have three each, while Boone, Benton, Camden, and Taney counties have two caves each. Sixteen caves in the state have one of the following words as the first or primary word in their name: Moonshine, Whiskey, Still, Beer, Bootlegger, and Brewery.

Times have changed, and whiskey making in the caves of the Ozarks appears to be a colorful cottage industry of the past. Today, it seems, cave enthusiasts who venture into the Ozark hills have more to fear from the guardians of methamphetamine labs, marijuana growers, and black-market artifact hunters than from the guardians of moonshine stills.

But there was a time when Civil War guerrillas used Ozark caves as hideouts, and outlaws of the Reconstruction years also took refuge in the caves. The outlaws of the 1870s and later were such a problem in the Ozarks that for a time people called Missouri “the Outlaw State.”