8

War and Outlaws

Local authorities claim the ubiquitous James boys used the cave [James Brothers Cave, Jackson County] for a hideaway. The boys would appear, considering all the claims of this kind, to have been Missouri’s first and most active spelunkers.

—J HARLEN BRETZ, Caves of Missouri, 1956

While many Missouri caves were put to benign and beneficial uses in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, some caves served the needs of criminals, Civil War guerrillas, Reconstruction-period outlaws, and hate groups. Civil defense and military authorities have also left footprints on the pages of Missouri cave history. It began early.

Honest, law-abiding immigrants were not alone as they crossed the Mississippi River and made their way into the Ozarks in the 1830s. The criminal element came along, too. One group of criminals chose to settle in the shadowy dells of a geologically unusual place that would later be known as Ha Ha Tonka in Camden County.

A man named Garland came to Ha Ha Tonka first. He built a gristmill and dammed the flow of Ha Ha Tonka Spring in 1830. Legend holds that he was the front man for outlaws and that the gristmill operation was simply to cover future criminal activities. There are many unknowns in this troubled period in the history of Ha Ha Tonka. It may be that the outlaws and counterfeiters who hunkered down here in 1831 came from Cave-in-Rock along the Ohio River or had close ties to the criminal dynasty that inhabited that locale for many years.

Cave-in-Rock is a cave in a bluff at the southern tip of Illinois along the Ohio River about eighty miles east of Cape Girardeau, Missouri, where nineteenth-century river pirates and counterfeiters operated for many years, preying upon traffic that came down the Ohio. They left a bloody history in the Cave-in-Rock area.

Among the outlaws at Cave-in-Rock was a man named Sturdevant, who became a notorious and successful counterfeiter during the settlement period. He was an artist at his illegal trade, an engraver of unequaled skill. He was also ruthless and headed a network of counterfeiting operations throughout the western country. He had rules for his talented subordinates—they were not allowed to pass counterfeit bank notes and coins in the area or state in which they operated, and they were to surround themselves with loyal criminals who would defend them and cover their counterfeiting activities.

When the criminals had to flee Cave-in-Rock country, Sturdevant disappeared. What became of him is not known, but there is reason to believe that he might have been at Ha Ha Tonka for a time or that the gang located there was an extension of his counterfeiting network. When the gang set up shop in several caves at Ha Ha Tonka, they brought with them skillfully engraved plates, presses, and molds. They set about manufacturing high-quality Mexican, Canadian, and American coins and bank notes, just as Sturdevant had been doing in the Cave-in-Rock area. The Ha Ha Tonka counterfeiters did not circulate the money in their area. Reportedly, they shipped the fake currency down the Osage River to the Missouri River to be taken elsewhere.

Unfortunately for the counterfeiters, the criminal element they depended upon for protection committed too many local crimes. The law-abiding settlers organized a “vigilance committee” with enforcers known as “the Slickers.” When a suspect outlaw was caught, he was tied to a tree, whipped severely, and ordered to leave the area. The technique backfired because the outlaws organized an “Anti-Slicker” force, and in the late 1830s the Niangua and Osage river valleys became embroiled in the Slicker War.

It was a violent and fearful time that led to several deaths. The war did not end until after the county was organized in 1841 as Kinderhook County, a name changed soon afterward to Camden County. Organization of the county government brought the Ha Ha Tonka area into the county’s jurisdiction, making it possible for local, state, and federal authorities to join forces and put an end to the outlaw operation.

The Slicker War was but a prelude to a bloodier conflict that erupted in the 1850s along the Missouri-Kansas border, a fight between proslavery and abolitionist settlers on both sides of the state boundary. The hate spawned by this prelude to the Civil War gave birth to outlaw gangs that would bathe Missouri in blood well through the 1870s. Chief among the outlaws were Jesse James, Cole Younger, and their followers and imitators.

The Civil War itself was destined to leave a legacy of folklore surrounding Missouri caves. Scores of caves in the Ozarks are at the center of legends and tales about men who hid out in the caves to avoid conscription, of families and small villages that hid their valuables in caves to keep them safe from guerrilla raids, and of Union and Confederate forces that used caves for the storage of munitions and other supplies.

After the Confederate victory at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in 1861 and later defeat at Pea Ridge, the larger forces of the Confederacy were kept out of Missouri by Federal troops. Federal patrols controlled the major rivers and roads of the state, but insurgents and Confederate sympathizers controlled the backwoods. Bands of guerrillas roamed the hills. Many of their rendezvous points were at caves, and a network of cave hideouts made it possible for them to have a nearly free run of the Ozark region.

Among the more notorious guerrillas that haunted the regions of central Missouri where caves are numerous—along the Gasconade and Big and Little Piney rivers—were secessionist “General Crabtree,” Bill Wilson, Jim Jamison, Anthony Wright, and Dick Kitchen.

Secessionist Crabtree came north at the beginning of the war, reportedly to recruit Cole and Miller county men to fight for the Southern cause. To the displeasure of Miller County residents, he stayed in the area to raid, making his headquarters in caves, moving frequently from cave to cave to avoid Federal patrols. Crabtree eluded capture due largely to his network of cave hideouts but met his end in August 1864 when he received a fatal wound. He managed to get back to his cave home, where a woman he had been living with was waiting. Though his enemies pursued him, he was left to die in the arms of the woman, who claimed to be his lawful wife. He was buried nearby in an unmarked grave in Cole County. The cave in which he died is known to this day as Crabtree Cave.

East of Miller County along the Little and Big Piney rivers, Bill Wilson and his guerrilla band were carrying out their own backwoods vendettas against Federal patrols. They also engaged in a great deal of looting and burning of homes and barns. Caves known to have been important links in Wilson’s escape routes after bloody encounters with soldiers included Huffman Cave, Gourd Creek Cave, Renaud Cave, and Point Bluff Cave, all in Phelps County. After the war, Bill Wilson and most of his bushwhacking buddies fled central Missouri, and Wilson himself was never heard from again.

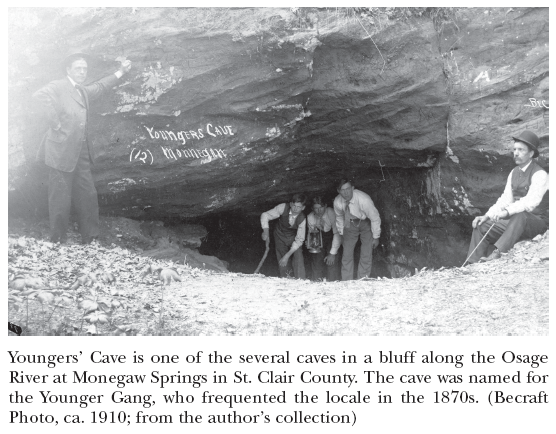

The Civil War left many areas of the Ozarks in chaos. Into this bitter state of affairs rode the James Gang, the Youngers, and a host of lesser outlaws. They robbed banks and railroads and created such havoc that, for a time, Missouri was called “the Outlaw State.” Some people scoff at the many tales, traditions, and legends that associate Jesse James with Missouri caves. Time erases documentation, and legends grow as the years increase.

Victims of the crime sprees perpetrated by the outlaws were never sure what outlaw was riding with whom at the time of a robbery. Imagination and the inability to identify Jesse James resulted in many erroneous stories. Some tales placed Jesse James pulling robberies in two different states at the same time. And it is quite possible that when members of these outlaw gangs were spotted in remote Ozark locales, people just assumed they were using a local cave as a hideout. So cave hideout stories multiplied.

When the show cave industry sprang up in the Ozarks in the 1880s and 1890s, the Jesse James saga was still a hot topic of conversation even though Jesse was killed in 1882. Show cave developers began to promote their own outlaw legends to add mystery and suspense to the history of their attraction. The one show cave that has bested all the others in advancing its Jesse James legend is Meramec Caverns near Stanton.

Cave names lead us to many of these stories that hark back to the days of the Civil War and the turbulent outlaw years that followed. There are three caves called Civil War Cave, one each in Camden, Christian, and Vernon counties. Perry and Polk counties both have an Ambush Cave. The Baldknobbers, a much-feared vigilante group in the Taney County area between 1865 and 1884, have a cluster of caves in Christian, Stone, and Taney counties named for them. There is one cave in Stone County called Belle Starr Cave and two Outlaw caves, one each in Franklin and Phelps counties. Belle Starr was known in southwest Missouri as “the Bandit Queen”; from 1875 to 1880, she led a band of cattle and horse thieves. Benton County has a Bushwhacker Cave, as do Pulaski and Texas counties. Vernon County just happens to have four caves named Bushwhacker, as well as a Quantrill Cave, named for the Confederate guerrilla William Clarke Quantrill.

Shannon County has a Peter Renfro Cave. Peter Renfro was a villain that most Missourians of today have never heard of, but in the 1880s and 1890s, his name was on the lips of just about everybody who lived in southern Missouri. In July 1888, Renfro killed Constable Charles Dorris during a brawl at a picnic in Summerville, along the Shannon-Texas county line, and then fled into the hills. All efforts to find him failed. It was rumored he had left the state. But then a new rumor surfaced, suggesting that he was hiding in a cave not far from his home. A search was made and the cave was located, but the cave entrance was down on the face of a cliff and could only be approached by descent from above—which was considered suicide. The cave reportedly had other entrances, but law officers could not find them. The officers were also unable to catch the person or persons said to be getting food to Renfro.

Renfro was captured at the cave about a year later. He was confined to the Springfield jail for two years, tried for murder, convicted, and sentenced to hang. But a week before the sentence was to be carried out, he escaped by overpowering his jailer and taking the keys from him. Peter Renfro disappeared again, but this time he covered his tracks so well that no one could find him.

In 1893 a newspaper article appeared describing his cave hideout. The newspaper reporter, who would not reveal the location of Renfro’s cave, said Renfro was constantly armed and had a faithful, well-trained watchdog. Renfro might have escaped capture for a decade or more if he had chosen to remain an underground recluse, but he didn’t. In February 1898, five years later, he was captured at the old Doniphan Club House in upper Ripley County. Judge McAfee of the Greene County criminal court resentenced Renfro to be hanged, but a petition circulated in southern Missouri, pleading for the governor to commute Renfro’s sentence to life in prison. On May 12, 1898, Missouri governor Lon V. Stephens granted the request and Renfro spent his last years in the state penitentiary at Jefferson City.

Between 1915 and 1925, caves in Greene, Jasper, and Newton counties became the meeting places for the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), a secret fraternal group that confined its membership to American-born white Protestants; it was originally formed to maintain white supremacy and later opposed immigrants and non-Protestant religious groups. In 1924, the Springfield Klan purchased Knox Cave northwest of the city, which was the site of an underground nightclub. For six years, the Klan used the cave as a “temple.” Unable to meet mortgage payments, the Klan eventually lost the cave, which later became a show cave under the name Temple Caverns. Today, it is called Fantastic Caverns.

In Newton County the Klan made use of Jolly Cave in the upper reaches of Capps Creek near its junction with Shoal Creek in the eastern part of the county. Jolly Cave is essentially one large room about 200 feet long, 40 to 60 feet wide, and 10 to 20 feet high with a nearly level, hard-packed clay floor. It is said that when the KKK used the cave, they would lead their horses down into the cave and stable them there. How long the KKK used the cave is currently unknown. The use of caves by the Ku Klux Klan seems to have been a phenomenon only of the 1920s, when the Klan experienced a short rebirth nationwide.

Events of World War II and the emergence of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union again turned attention to the possibilities of Missouri caves. In the late 1940s, the U.S. Navy surveyed some three hundred caves within a fifty-mile radius of Rolla, Missouri, looking for one suitable to house a jet propulsion laboratory. The navy’s project, called “Project Cavern,” was a military secret for many years. This 1951 project was carried out by a U.S. Naval Reserve attachment at Rolla, Missouri. An early report on Project Cavern produced by the Office of Naval Research was published in Missouri Speleology, the journal of the Missouri Speleological Survey (MSS), in 2005.

In the early 1960s, Missouri civil defense authorities came to the MSS requesting information and locations for Missouri caves. They wanted to see how many caves might be usable as fallout shelters, where people could go for protection in the event of a nuclear attack. The Missouri Civil Defense Agency in Jefferson City eventually released the “Mine and Cave Fallout Shelter Survey,” which listed 212 wild caves scattered across thirty-eight Missouri counties. They were caves that had at least one thousand square feet of floor space that might be suitable for the agency’s purposes.

Fortunately, neither the owners of the wild caves nor civil defense authorities rushed out to convert the caves into actual fallout shelters, which could have resulted in irreparable damage to many caves. The caves did, however, receive official designation with metal Fallout Shelter signs posted near their entrances listing each cave’s holding capacity (the number of people the cave could accommodate in an emergency).

For Missouri show cave operators it was a different matter entirely. They leaped to the cause, seeing it as an opportunity for free publicity. A news release published in the Reveille newspaper at Camdenton, on November 14, 1961, reported that the Missouri Caves Association assisted the state civil defense director, Dean Lupkey, in setting up an advisory committee on the use of caves as fallout shelters. Eddie Miller, manager of Bridal Cave, served as chairman, with committee members Bob Hudson of Meramec Caverns, Waldo Powell of Fairy Cave, and Ohle Ohlson of Ozark Caverns.

The show caves reaped tons of publicity with the issue and were still benefiting from Cold War scares as late as 1969 when civil defense supplies were still being stashed away in various show caves throughout the state.

Murders, thieves, counterfeiters, guerrillas, and hooded hoodlums have come and gone in the darkness of Missouri caves. They accomplished little other than leaving a legacy of legends that have perpetuated their names and the memory of their unsavory behavior. Even the designs of well-meaning military authorities and civil defense officials came to naught when they turned their attention to the caves of Missouri. The caves survived largely intact and undamaged by the plans and activities of these agents, but many caves in the Ozarks did not fare so well when they caught the attention of onyx miners during the late nineteenth century.