9

Onyx Mining

For several years the attention of scientists and lapidaries has been attracted to the wonderful deposits of onyx in Central Missouri. The residents in the neighborhood of the caves and the owners of the land upon which they are located, until very recently, did not know and appreciate the value of the wealth stored in them.

—New Era newspaper, March 14, 1891

“Throughout the Ozark region there are caves in the dolomite and limestone formations . . . filled in whole or in part with travertine, or cave onyx, as it is called. This onyx resembles the Mexican variety and often, when polished, exhibits beautiful surfaces, having a variegated coloring,” wrote state geologist Henry A. Buehler in The Biennial Report of the State Geologist, published by the Missouri Bureau of Geology and Mines in 1906. “But,” Buehler noted, “it is seldom obtainable in large blocks free from flaws, for which reason attempts to exploit these deposits have been abandoned.”

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, polished marble was much in demand throughout the world for ornamental and decorative interior and exterior architectural work. The stone was used for many purposes, including flooring, mantels, paneling, clock cases, lamp bases, tabletops, washbasins, statuary, vases, and columns. It was commonly used in public buildings and luxury homes.

In the stone trade, the term marble is applied to any rock containing large amounts of calcium carbonate that is capable of taking a good polish and is suitable for ornamental work or high-grade construction. For commercial use, the rock must have a desirable color, be able to be quarried in blocks of large size free from cracks or impure layers, and have a fine texture.

The most suitable stone for this purpose is crystalline limestone and dolomite, which formed as sediment in shallow waters of inland seas between 100 and 500 million years ago. These rocks are generally composed of more than 50 percent carbonate minerals, which were derived from the skeletons and shells of ancient sea life that died and settled to the bottom of the seas. There is a great range in color, the most common being variations and mixtures of gray, white, black, yellow, pink, and green. The colors are largely due to impurities that give the stone a “banded” or “grained” appearance.

Beds of marble occur in many geologic formations. Because marble comes in such variety and from so many parts of the world, it is a stone of many names. But among these names are certain ones that have a special meaning to jewelers and craftsmen, and which were especially popular in the closing years of the nineteenth century. These terms are onyx, cave onyx, onyx marble, Mexican onyx, black onyx, and travertine.

Onyx marble and onyx differ somewhat from marbles of the common type. Marbles commonly used in high-grade construction are from bedrock layers of limestone and dolomite. But onyx marble and onyx are essentially crystalline deposits derived from the dissolving and breaking down of limestone and dolomite by groundwater. Onyx marbles form in one of two ways—as the product of hot springwater deposits that develop on the surface at a spring outlet, or as deposits left by cold, mineral-laden drip water in caves. The deposits formed by hot springs are generally called travertine or tufa, such as the famous travertine or tufa deposits in Yellowstone National Park. The deposits left by drip water in caves takes the form of stalactites, stalagmites, columns, and flowstone on the floors, walls, and ceiling of limestone caverns. It is the cold-water deposits that are generally called cave onyx or onyx. The term black onyx refers to a form of onyx marble that is pure black. Mexican onyx is largely a form of travertine or onyx marble that is quarried and processed in Mexico.

Since the late 1800s, much of the world’s finest onyx marble has been produced by Mexico. At most quarry sites, this stone has been of the banded travertine variety, but some had originally formed in caves that later had their walls and roofs destroyed by erosion, leaving the cave onyx deposits on the surface. Cave onyx and other onyx marbles were first brought to the attention of architects, sculptors, and builders in 1862, when the French made a large, beautiful display with it at the International Exhibition of London. The exhibit was fashioned from stalagmite formations found in Algiers. Onyx was also displayed at later expositions, including the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904.

In the late 1880s, mining entrepreneurs in the United States began searching for deposits of cave onyx in the caves of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri. These states are noted for having many caves formed in limestone and dolomite, caves adorned with formations composed of cave onyx. By December 1890, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat newspaper was promoting the discoveries of prospectors who wanted to exploit local cave onyx deposits. These speculators, the paper said in headlines, had found “miles of subterranean wonders—onyx of all colors and immeasurable extent—great chambers lined with the beautiful stone.” The best deposits, according to the reports, were found in caves in Crawford and Pulaski counties, Missouri. “Millions in Onyx” said at least one newspaper headline in 1891. This article went on to report that a company had been formed in St. Louis to work the deposits in Crawford and Pulaski counties.

“Experts from different parts of the country were secured and all the caves in Pulaski and Crawford counties . . . were inspected,” the New Era newspaper reported in March 1891. “The result of the investigation satisfied the members of the syndicate that they had come into possession of a veritable bonanza. Onyx was found in nearly all of the caves, but only in small quantities in most of them. The main formation seemed to be in three caves and four open workings.” Two of the caves and quarries were located in Crawford County, and one cave and two quarries in Pulaski County, according to the paper. The unnamed cave in Pulaski County was Onyx Cave, about five miles northeast of St. Robert. This cave was sometimes called Boiling Springs Cave. In the 1990s, it was a show cave, operated as Onyx Mountain Caverns.

The surface quarries in Missouri that contained onyx deposits were, in the language of that day, “broken down caves,” or in other words, very ancient caves that had been unroofed and destroyed by surface erosion.

Onyx mining began at Onyx Mountain Caverns in 1892. The stone was destined for use in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch building in St. Louis and at other sites. Work started with the sinking of a deep shaft, eight feet by thirteen feet, to reach the deposits that were located nearly a thousand feet into the cave from its natural entrance. The shaft penetrated eight feet of soil and loose rock and then ninety-two feet of solid rock before entering the cave. A substantial amount of onyx was removed from the cave chamber at the bottom of the shaft, as well as from a nearly onyx-filled passage that leads from the shaft chamber back toward the cave’s natural entrance. Work at the cave continued until it became apparent that much of the stone removed from the cave was commercially unusable. It was riddled with minute fissures that caused the stone to break apart when being cut and shaped at the finishing plant in St. Louis. While suitable for carved figurines and similar small souvenirs, it was unsuitable for projects that required large slabs or blocks of stone.

George P. Merrill, the curator of the Department of Geology at the U.S. National Museum, was the leading authority on onyx marbles in the 1890s. In an 1895 report on the cave onyx mining industry, he stated that there were some disastrous cave onyx mining failures during this period. He attributed it to the incompetence of those who evaluated the volume and quality of the onyx deposits, to the incompetence of the miners who used explosives (which weakened the stone), and to promoters of the industry who had unrealistic expectations.

It became apparent in the decades that followed that most Missouri cave onyx was too flawed for use in construction due to interruptions in the way its layers were deposited over geologic time. But knowledge, wisdom, and experience were apparently in short supply among the cave onyx miners of Missouri from the 1890s to the 1920s. Most had probably never heard of George P. Merrill or read his reports. Most of them had probably not even consulted Missouri’s own state geologist, Henry A. Buehler.

The mining at Onyx Mountain Caverns encouraged other onyx mining ventures. By the mid-1890s it was known that the World’s Fair was going to be held in St. Louis in 1904. Speculators were sure that architects planning the Missouri buildings for the fair would want cave onyx for decorative uses. Mining entrepreneurs went hunting for caves with suitable deposits of onyx to quarry. By 1893, several caves in Camden County were the focus of onyx mining activities. These caves included King’s Onyx Cave and several small adjacent caves near the vanished town of Barnumton, which were totally stripped of their deposits. By 1897 Onyx Cave, along the Big Niangua River about 16.5 miles above its confluence with the Osage River, was also being mined. Today, the waters of the Lake of the Ozarks inundate the onyx-mined portions of this cave.

Big Onyx Cave in Crawford County was subjected to so much blasting that it became unstable, and portions of the cave collapsed. Not far away, in the same county, was Onondaga Cave, where an abortive attempt was also made at mining onyx. In the 1890s, a man named Brown quarried onyx in Onyx Cave about eighteen miles from West Plains in Howell County, reportedly removing thirty tons. Thirty-six years later, in 1928, his son considered reestablishing the onyx mining operation but was apparently persuaded not to do so after a geologist from the Missouri Bureau of Geology and Mines evaluated the site.

By 1901, contractors for the World’s Fair announced that they wanted Missouri cave onyx to exhibit in the Mining and Mineralogy Hall and possibly for some of the buildings to be erected. Spurred by this, two engineering students at the Missouri School of Mines and Metallurgy—Ignatius J. Stauber and Fred R. Koeberlin—visited Onyx Mountain Caverns to study the cave’s geology and reevaluate its onyx deposits. The bulk of their twenty-four-page thesis was devoted to the possibilities of reopening the mine. In their final analysis, Stauber and Koeberlin were not encouraging about the prospects of reopening the mine. Their concluding paragraph stated: “It should be born in mind however, that there is a great element of uncertainty in working deposits of this kind, as they are rarely uniform for any great distance either in texture or color and the enterprise necessarily partakes of the nature of a lottery.” The cave mine was never reopened.

In February 1911, the Missouri State Capitol building in Jefferson City burned. A temporary capitol building was quickly erected nearby and preparations began for the construction of a new permanent capitol building. This also spurred new onyx mining ventures. The Onyx Quarries Company of Boonville filed its corporate papers in 1919 and began development of a mining operation at Arnhold Onyx Cave along the Niangua River in Camden County. This company, too, was destined to fold before removing substantial amounts of onyx. Today, this cave is inundated by the Lake of the Ozarks.

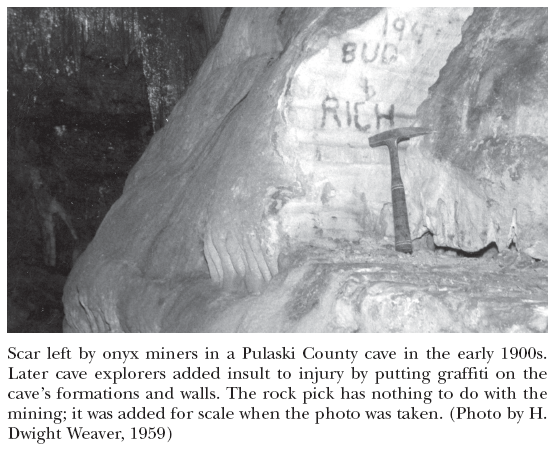

Cave onyx mining speculation continued into the 1930s in Missouri, but by the early 1920s the industry had become all but extinct in the state. Missouri cave onyx producers could not compete with the high quality, low-priced onyx marbles being marketed nationwide by companies in Arizona and California. The mining of onyx from caves in the United States was a short-lived industry that thrived from about 1890 to 1920 in Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The booming industry was lively and generated boastful newspaper headlines full of speculation and exaggeration. It led to some disastrous financial failures and irreparable damage to a number of beautifully decorated caves.

The history of the onyx mining industry in Missouri’s past makes an interesting statement about the attitude of society toward caves during the 1890s and early 1900s. During this period, large segments of society considered caves to be worthless unless they contained some substance of commercial value or could be used for recreation. We are fortunate that the onyx mining industry folded before it was able to damage and destroy more caves than it did, because the miners focused their attention on those caves that were the most beautifully adorned by nature.

Another group of miners who went looking for caves during this same period in Missouri history were seeking a different kind of resource, one that was less solid and more squalid—bat guano. They too had visions of wealth dancing in their heads.