10

Guano Mining

The local wise men all laughed at Weekly when he began his operations [bat guano mining], and were much chagrined when they learned that he had sold the first shipment for $500.

—VANCE RANDOLPH, “Cave Bats and a Unique Industry,” Missouri Magazine, August 1934

“Some months ago a large cave was discovered in Stone County. . . . A company was organized to develop its varied stores of wealth in the shape of marble, fuller’s earth, etc. but little was said of the real wealth, which covered the floor . . . to a depth of several feet. That was kept in the background, and the widely published stories of the cave attracted but little attention,” reported the Current Wave newspaper on October 1, 1884. The deposits were later analyzed and found to be bat guano, which the newspaper called “the richest guano on the globe, surpassing the famous Peruvian beds, from which the world has drawn its supplies for more than half a century.”

As soon as the public learned that the guano was valuable, the news created great excitement in southwest Missouri. Prospectors went hunting for caves with similar deposits of guano. As a consequence, numerous guano mines were established in caves in Stone and Christian counties. “Shipments are being made daily to the markets of the east where it commands a high figure for fertilizing purposes,” reported the newspaper. “Prospecting parties are out in every direction, and it is safe to say that every hill and hollow of Stone, Christian, Taney and Ozark counties will be more thoroughly explored than they ever were before, and that every hole will be investigated.”

Saltpeter miners had been the first to go looking for deposits of bat guano in Ozark caves, because saltpeter, one of the principal ingredients in gunpowder produced in the early 1800s, can be leached from aging guano. But later, bat guano was sought for its fertilizer value.

Fresh bat guano is black. It has a high moisture content, much nitrogen, and appreciable amounts of phosphorous and potassium—the desirable elements for fertilizers. With age, the guano loses moisture and becomes a dark brown. Very old bat guano can be reddish, pale brown, or gray and becomes quite dusty, unless it is in a cave area where it is subjected to large amounts of dripping water or is periodically inundated by a flooding cave stream.

The chemistry of the bat guano changes as it ages, and the nitrogen changes into ammonia and nitrate. In some instances, bat guano can saturate the cave air with ammonia fumes to a degree that breathing the air becomes dangerous. C. L. Weekly, who mined bat guano from Gentry Cave near Galena, Missouri, in the 1930s, acknowledged this hazard in guano mining. He said he had been forced to abandon some of his guano sites because the cave passages were small and the ammonia fumes were too strong.

The large, unidentified cave mentioned in the 1884 Current Wave article was Marvel Cave in Stone County. Ronald L. Martin, in the Official Guide to Marvel Cave: Its Discovery and Exploration, first published in 1974, documented the guano mining activities that occurred in this large, deep, spectacular Ozark cave. The mining enterprise began in 1884 and lasted until about 1888. The operation must have been an impressive enterprise in the Ozark hills of that day, because the guano had to be brought to the surface in buckets from a depth of more than a hundred feet. The piles of guano in the great, domed entrance chamber of the cave were twenty-five feet deep. At that time, the market value of the guano, after processing, was seven hundred dollars per ton.

Guano is generally considered to be the manure of seabirds such as pelicans, cormorants, and penguins. Bats are mammals, not birds, but at some early date the word guano became associated with the manure of bats, and the term has been used ever since. The islands off the coast of Peru have long been the chief source of supply for guano used as fertilizer around the world, but the guano mining that occurred at Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico from 1903 to 1923 is one of the best-known former guano mining enterprises in the United States. Carlsbad Caverns is one of America’s most popular show caves. Millions of people have toured the cave since 1925 and learned about this episode in the cave’s history when more than a hundred thousand tons of guano were removed from the cave.

In 1921, the University of Missouri College of Agriculture released a study by William A. Albrecht (bulletin 180) titled “Bat Guano and Its Fertilizing Value.” “The high cost of manufactured fertilizers and the shortage of nitrogenous materials, together with transportation troubles of the past few years, have put precarious conditions about the farmer dependent on commercial fertilizer,” said Albrecht. The report went on to mention the various kinds of fertilizers that the farmers would have to resort to using and then encouraged the use of bat guano. “Bat guano . . . should have attention for its possibilities in this respect . . . since caves with bats inhabiting them are common in Missouri.”

Albrecht’s report concluded, “Average bat guano makes a good fertilizer on poor soils when applied directly at the rate of two hundreds pounds of dry material per acre. As a general fertilizing material it can be used more satisfactorily as a constituent of mixed fertilizer, especially when mixed with phosphorus carriers.”

In 1883–1884, a financial panic and depression overtook the nation. It was particularly hard on farmers. This was the economic situation in 1884 when guano mining began in southern Missouri. But the industry seems to have not survived much beyond 1890. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, there was another period of sporadic guano mining in the Ozarks, but the price commanded in 1884—seven hundred dollars per ton—fell to thirty to forty dollars per ton in the mid-1930s.

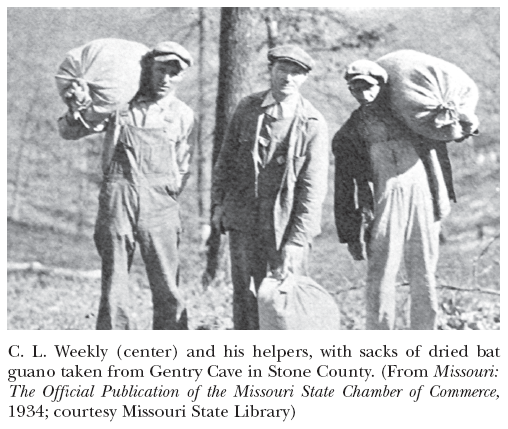

Missouri’s most noteworthy guano miner of the 1930s was C. L. Weekly of Stone County, who mined Gentry Cave along the James River. Gentry Cave has several doorwaylike openings beneath a rock shelter in a bluff. The cave is extensive, with a maze of intersecting passageways, some of crawling height only. When C. L. Weekly, a wiry, sharp-eyed man of small stature, worked the cave, he was known locally as the “Bat Manure Man.” He maintained that the guano he mined, processed, and sold was the best fertilizer in the world. “All the greenhouses use it. . . . I ship mine to Springfield and Kansas City and St. Louis, mostly. Get $35 a ton for it,” he told folklorist Vance Randolph in 1934. Upon being taken to a place in the cave where Weekly was working, Randolph noted that the guano deposits were five feet deep, dark brown, perfectly dry, and odorless.

When Weekly took his first shipment of guano to the railroad station and asked for freight-rates on the product, the man at the station thought he was crazy and had difficulty finding the proper rate, because he didn’t know what kind of animal a bat was. A nearby loafer, overhearing the conversation, cried out, “My Gosh! Thar ain’t bats enough in th’ world to make a carload o’ th’ dang stuff!” Weekly soon proved him wrong.

Weekly and his two helpers wore caps with oil lamps, much like coal miners of that day. They shoveled the guano into big buckets and then carried the buckets to the cave entrance where the guano was spread out on the ground and left to dry. After the guano was dry, it was sifted through wire gravel-screens to remove fragments of rock and other undesirable material. Once sifted, it was put into hundred-pound sacks. Each sack carried a registration tag with a guaranteed chemical analysis, as was required by state law. Weekly’s first shipment consisted of 380 hundred-pound sacks, for which he was paid five hundred dollars. That was a handsome sum for Depression days in the Ozarks.

There were hazards to guano mining besides ammonia fumes. At some stages, some guano can be explosive, so using a lamp with a live flame is a hazard. Histoplasmosis, an infectious lung disease, can be contracted by inhaling dusty bat guano that contains spores of the histoplasmosis fungus. Bats themselves do not transmit the disease, but dusty bat guano is a suitable medium for development of the airborne spores of the fungus. It is highly unlikely that C. L. Weekly and his helpers used breathing masks while digging in the guano deposits, which, according to Randolph, were dry and probably quite dusty. Whether or not any of them contracted the lung disease is unknown.

Weekly said only one kind of bat used Gentry Cave. He probably did not know the species, but it was most likely the gray bat. He was also dismayed with the way bats were treated. “Many farmer boys seem to hate bats for some reason,” he said, “and sometimes make big wooden paddles and go into the caves where they kill bats by the hundreds.”

Missouri “currently provides habitat for eleven species of bats; in addition, four other species of bats have been observed here or may occur here,” according to William R. Elliott, cave biologist at the Missouri Department of Conservation. These bats feed exclusively on flying insects. Six of these species spend all or at least part of the year roosting in caves. Only the gray and Indiana bats leave large piles of guano in the caves—the gray bat, in particular, because it not only hibernates in the caves during the winter, but also uses caves as a nursery for rearing young.

Missouri law now protects bats. The Indiana and gray bats are also on the federal Endangered Species List and are thus given special protection. Some of the caves that harbor the largest colonies of gray and Indiana bats in the state are gated. The gates that are installed on bat cave entrances are of a special design that prevents human access yet allows the bats to fly in and out of the cave without harm or impediment. Bats are very particular about the kind of opening through which they will fly. Most bat gates are funded and installed by federal and state agencies, often with the assistance of organized caving groups. Some of Missouri’s organized caving groups have also funded the installation of bat gates. Occasionally, a private cave owner will finance such a gate for his cave but rely upon agencies and cavers to do the installation and often the maintenance. Access to these caves is not permitted when the bats are in residence, which means that exploration of the bat caves is possible for only a few weeks or months out of the year.

Only about a hundred of Missouri’s 6,200 recorded caves are suitable to gray and Indiana bats for hibernation and rearing their young. The limited number of usable caves, the increasing use of pesticides to control insects, an ever-increasing loss of habitat, and human disturbance have caused a serious decline in the population of these bats over the decades. Saltpeter mining during the settlement period and the guano mining that came later undoubtedly had an impact upon the bats that used the mined caves. Fortunately for the bats, the development of synthetic nitrates eliminated the need to mine saltpeter from caves to manufacture gunpowder and guano for the making of fertilizers.

It has only been during the latter half of the twentieth century that we have learned how truly useful bats can be. They consume enormous quantities of harmful flying insects. And it has only been in recent decades that Missouri has been able to create laws and develop and fund state agency programs designed to protect bats and the caves they use. Public education has progressed considerably since the days when the farmer boys of C. L. Weekly’s neighborhood went into caves to kill bats. It still happens occasionally, but today bats are more highly regarded than at any other time in recorded Western history.

The guano miners dug into many unsavory piles of bat manure, but in general they did not disturb the caves in a major way, and the substance they sought actually existed and had value. They were not like the many seekers of buried treasure who plundered Ozark caves in the 1930s and 1950s, chasing legends and figments of the imagination.