12

Picnics and Parties

Are you going to the grand picnic at Green’s Cave, July 3 & 4? Two big days, plenty to eat, plenty to drink, all kinds of amusements . . . fireworks at 9:30 p.m. Large dancing floor, good music, your friends expect to meet you there. Don’t disappoint them.

—Ad in Sullivan Sentinel, June 26, 1908

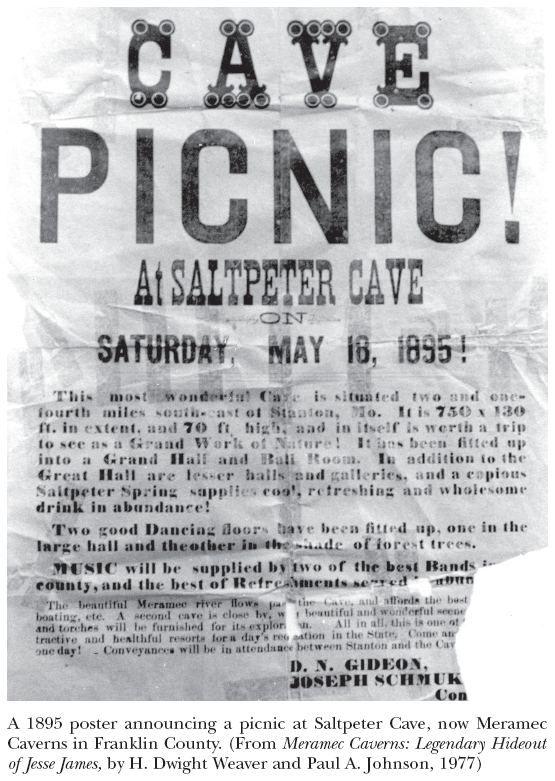

In 1895, D. N. Gideon made sure that the handbills advertising the cave picnic at Saltpeter Cave were nailed up in all the towns within a few hours’ buggy ride from the cave. And just to make sure the crowd would be large enough to guarantee that he and his partner, Joseph Schmuke, would clear a substantial profit, he informed A. Hilton, the passenger traffic manager of the Frisco Railroad, about the cave picnic. Hilton was always eager to promote events along the Frisco line that would fill the passenger seats in his trains between St. Louis and Springfield.

Gideon was a grocer and owned a general store in Stanton, a village along the railroad tracks in Franklin County. His partner, Joseph Schmuke, was the Stanton hotelkeeper and also the operator of one of Stanton’s saloons. The event was planned for Saturday, May 18, 1895. For Gideon and Schmuke, it was their first attempt at staging a cave picnic. “This most wonderful Cave is situated two and one-fourth miles southeast of Stanton, Mo. It is 750 × 130 ft. in extent, and 70 ft. high, and in itself is worth a trip to see as a Grand Work of Nature!” their handbill declared.

It has been fitted up into a Great Hall and Ball Room. In addition to the Great Hall are lesser halls and galleries, and a copious Saltpeter Spring supplies cool, refreshing and wholesome drink in abundance!

Two good Dancing floors have been fitted up, one in the large hall and the other in the shade of forest trees.

Music will be supplied by two of the best Bands in the county, and the best of Refreshments served in abundance.

The beautiful Meramec river flows past the Cave and affords the best swimming, boating, etc. A second cave is close by, with beautiful and wonderful scenes . . . torches will be furnished for its exploration.

The crowd that attended this first event at Saltpeter Cave found that the cave had a spacious entrance passage, and three hundred feet inside, it opened into an immense, circular chamber that had a hard-packed, smooth clay floor. There were even two wings to the ballroom that were also large chambers. The temperature of the cave was a pleasant sixty degrees, and there was almost no dripping water. Most of the entrance corridor and ballroom was pleasantly dry.

Besides the dance floors Gideon and Schmuke had constructed, they had secured lanterns about the walls and along the entrance corridor, built a bar in the cave, a platform for the musicians, cleared brush from the area outside the cave, tidied up the riverfront, and put the old wagon road down to the cave in passable shape.

The event was so successful that Gideon and Schmuke planned additional weekend parties. Word spread quickly up and down the Frisco line, and people from both St. Louis and Springfield began to attend the events. Hardly a summer weekend passed without some type of sponsored activity at the cave. Gideon and Schmuke prospered so well that they continued to sponsor summer dances and picnics at Saltpeter Cave until 1910.

Saltpeter Cave, known today as Meramec Caverns, was not the only cave where cave parties were held. Green’s Cave and Fisher Cave, upstream from Saltpeter Cave, were also party sites. The Sullivan family of Sullivan, and the Schwarzer and Bienke families of Washington, Missouri, sponsored activities at Fisher Cave. “Cave parties are numerous these days,” the Sullivan Sentinel reported in July 1901.

Occasionally the crowds were so large special arrangements were necessary. An event at Green’s Cave in July 1903 was typical. Sixty people from St. Louis were involved. In October 1905 an even larger event was staged at Fisher Cave and entertained so many people the local paper declined to list them all by name but reported that, at the height of the party, “people attending came from Gray Summit, St. Louis, Kansas City and Pacific. . . . The party lasted for three or four days and employed three colored cooks.”

The Franz Schwarzer family of Washington organized a “cave explorers club” to engage in spelunking and partying at numerous caves along the Meramec. S. H. Sullivan Jr. of Sullivan also organized a caving club. They were the first organized caving clubs in Missouri but were certainly not like the caving clubs we have today.

From 1885 to 1925, caves throughout the Ozarks witnessed the new phenomenon—a craze for cave picnics and parties. Electricity had arrived in the cities, but most homes and businesses did not yet have air-conditioning. Caves were an ideal setting for cool summertime fun.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the United States had an expanding middle class in urban centers that demanded leisure pursuits and were willing to pay for them. People turned to the outdoors for all kinds of recreational activities because it was also the age of America’s first fitness and health craze. Mineral waters and health spas were all the rage. Swimming, boating, bicycling, roller-skating, and ice-skating were new fads. Resorts began to appear all across the Ozarks. The Chautauqua had come to life in the 1870s, and by the 1880s it was spreading from coast to coast in the United States. Caves were ideal settings for these extravagances of oratory, music, and other performance entertainment.

At Uhrig’s Brewery Cave in St. Louis, the underground chambers were converted into a first-class theater by the St. Louis Coliseum Company, which had leased the property and constructed a new building over the cave entrance. When the underground venue, called the Coliseum, opened in 1909, the first user was the famed revivalist Gypsy Smith. In succeeding years Enrico Caruso sang there, Billy Sunday preached there, and Woodrow Wilson was nominated for president at the 1916 Democratic National Convention, said to have been held in the Coliseum.

Near Ash Grove in Greene County, a dance floor was constructed in a spacious chamber in Ash Grove Cave called the Ballroom. Spears Cave in Morgan County became the site of an annual Fourth of July picnic that drew crowds from several counties. The cave was often lighted so that people attending the event could explore the entire cave. “Splendid arrangements are being made for the celebration of the 4th at Spears Cave six miles southwest of Versailles,” said the Versailles Leader, June 25, 1891. “The Versailles Gun Club will have a pigeon shoot, a premium of $5 being offered for the best score. Premiums will also be paid for the winners in sack racing and pole climbing. There will be an abundance of amusements.”

At Stark Caverns, south of Eldon in Miller County, an underground dance floor and roller rink was built about two hundred feet back inside the cave. The parties there drew good crowds. In the winter, the cave stream would freeze inside the cave entrance, and ice-skating became an added entertainment. Dance pavilions existed in Crystal Cave at Joplin, St. James Tunnel Cave in Phelps County, Steckle Cave in Pulaski County, Harrington Cave in Perry County, Speakeasy Cave in Greene County, and at many other caves throughout the Ozarks.

The 1890–1920 period was a lively phase in Missouri cave history but also one of the most destructive. Onyx mining was in full bloom, and onyx novelties were everywhere in urban and resort gift shops. Unrestricted and unguided cave exploration was nearly always an added entertainment at cave picnics and parties if the cave was extensive or there were adjacent caves with easy access. Some of the caving led to major discoveries, but since no code of caving ethics had yet been established and destructive activities were not frowned upon during this period, the caves saw considerable damage. It became popular to take home “a piece of the cave” as a souvenir. Chunks of cave onyx were popular as doorstops. Stalactites wound up as mantelpieces and conversation starters, as inclusions in rock gardens, retaining walls, cottage walls, and whatever other ornamental use the owner of the souvenir fancied. Stalagmites even found their way into cemeteries as tombstones.

Luella Owen, who was doing research for her book Cave Regions of the Ozarks and Black Hills of South Dakota, published in 1898, noticed the destruction and spoke out against it:

Unfortunately, most of the caves in this region [the Ozarks] have been deprived of great quantities of their beautiful adornment by visitors who are allowed to choose the best and remove it in such quantities as may suit their convenience and pleasure. Those who own the caves, and those who visit them, would do well to remember that if all the natural adornment should be allowed to remain in its original position, it would continue to afford pleasure to many persons for an indefinite time; but if broken, removed, and scattered the pleasure to a few will be comparatively little and that short-lived. The gift of beauty should always be honored and protected for the public good.

Unfortunately, hers was a voice crying out in the wilderness. Her book saw little public exposure and even when it was read during those years, it probably made little impression upon a generation for whom the word inexhaustible was applied to any underground resource, onyx cave formations in particular.

Cave owners allowed far too many of the picnic and party attendees to vandalize their caves. Far too many of the people who participated in the caving activities indulged in vandalism, breaking formations and defacing cave walls, ceilings, and boulders with carved, smoked, and painted names, dates, and other graffiti. The damage that was done to cave formations endures to this day. Much of the disfigurement that we see in both wild caves and show caves dates to this period. Most of the damaged formations will be disfigured forever. Nature cannot heal them, even in the lifetimes of hundreds of generations of people.

Modern technology has given us the tools to repair some of the damage to cave formations, but only if the broken pieces are not too shattered and are still lying nearby in the cave. Cavers are repairing some of the broken stalactites, stalagmites, and columns in Missouri caves, but it is painstaking, time-consuming work, most of which will probably never be seen nor appreciated except by fellow cavers. It is admirable work done out of love for the cave, but so much damage was done to Ozark caves during that one period that repairing one formation is like polishing one seashell on a shell-littered beach the size of an ocean.

Unfortunately, our caves are still under attack by vandals. The tradition of writing names and dates in caves continues to this day in wild caves, as does the indiscriminate handling, breaking, and destruction of cave formations.

It happened as recently as five years ago at River Bluff Cave at Springfield, Missouri. According to Matt Forir, lead paleontologist at River Bluff Cave, three young men broke into the gated cave, carved their initials at the base of a beautiful cave formation, and then wrote that they explored the cave (illegally) on April 26, 2002. They also scattered the fossil bones of a snake and left footprints in sensitive areas noted for fossil animal tracks. Fortunately, the vandals were caught, convicted, and sentenced to three years in prison. “I am somewhat sure that this has been the worst punishment for cave vandalism in the state and probably the country,” said Forir. Fortunately, some of the damage was repairable to the extent that it is not apparent to a casual observer, but this kind of resource destruction always leaves scars that can never be healed.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were at least a few responsible promoters of cave picnics and parties. When Gideon and Schmuke held events in Saltpeter Cave, people were not allowed to litter the cave or write on the walls. During one of the caving expeditions in 1901, a major discovery was made in Saltpeter Cave—unbelievably beautiful upper levels of the cave were found. Until then, the cave had been thought to end just beyond the ballroom. Immediately afterward, that portion of the cave became a new attraction, and people who came to the dances were allowed to tour the upper sections—but they were not allowed to handle or break formations and not permitted to disfigure the cave with graffiti. As a consequence, in 1933, Lester B. Dill was able to open the cave to the public as a show cave, and since that date millions of people have had their breath taken away by the exquisite beauty of the Stage Curtains in Meramec Caverns.

Show caves, which made their first appearance in the 1880s, have definitely made a difference in Missouri.