13

Show Caves

The Ozarks would give up almost everything before she would her caves and rivers, they mean too much as tourist attractions.

—JOE TAYLOR, “Tourist Gold the Buried Treasure,” Missouri Magazine, June 1934

Caves were among the first natural geographic features of Missouri to be commercially developed and promoted as tourist attractions. About 10 percent of the people who come to the state each year as tourists visit a show cave. Missouri has more show caves than any other state, and the caves are widely known for their beauty and history.

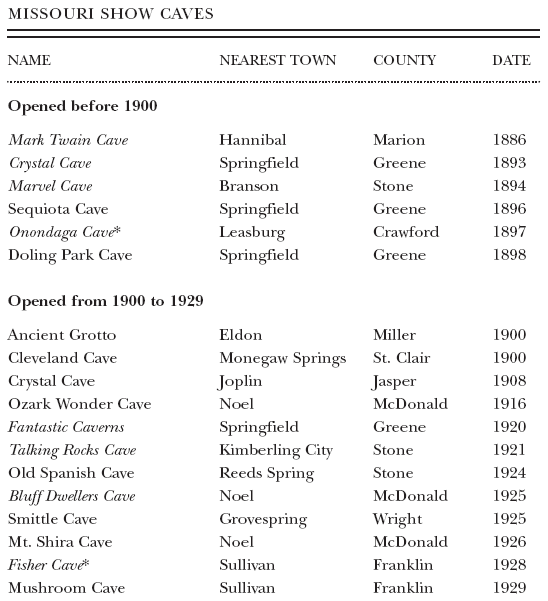

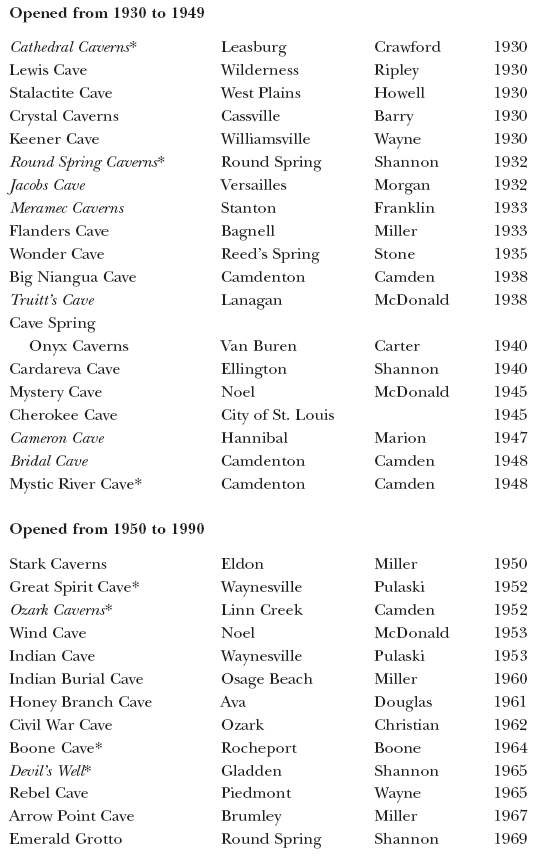

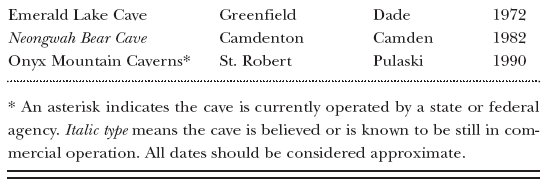

A show cave is defined in Missouri law as “any cave or cavern wherein trails have been created and some type of lighting provided by the owner or operator for purpose of exhibition to the general public as a profit or nonprofit enterprise, wherein a fee is generally collected for entry.” The number of show caves open to the public in Missouri has varied from year to year and decade to decade, depending upon the circumstances that attend each cave operation, regardless of whether the ownership is federal, state, or private. Over the past 150 years, more than fifty Missouri caves have been exhibited to the public as show caves.

A commercial cave is any cave or cavern that is developed and operated for profit, be it for exhibition, as a theater, as a restaurant, or for some other commercial activity. A commercial show cave, therefore, is a commercial cave that is open to the public primarily to exhibit its natural features.

A wild cave is any cave in its natural condition—a cave that has not been modified for some human purpose. These are the caves most closely identified with the activities of organized spelunking groups who explore, map, and study caves. Some generally noncaving segments of the public, however, do occasionally go caving in wild caves through structured outdoor educational and recreational adventure programs. Both the Missouri Department of Natural Resources and the Missouri Department of Conservation have and use wild caves that they own and manage for educating the public about cave resources.

Tumbling Creek Cave (Ozark Underground Laboratory) in Taney County has visitor trails, yet it fits none of the above categories. Its visitors are generally limited to college students during science course work, or geologists, biologists, and other scientists doing cave-related research.

Notable commercial caves of the early and mid-1800s included a host of caves in St. Louis that were converted into storage and cooling facilities for breweries and wineries, underground beer gardens, theaters, mushroom farms, and cheese-manufacturing plants. English Cave, which is believed to still exist beneath Benton Park in south St. Louis, and Uhrig’s Cave, a former brewery cave along Market Street, were actually operated as show caves for brief periods between the 1840s and the 1890s.

Most of the old St. Louis Brewery caves are now sealed and no longer accessible, and some have actually been filled in or otherwise destroyed. One of the former brewery caves in St. Louis that still exists in fragments is Cherokee Cave, which became a celebrated Missouri show cave from 1945 to 1961. The cave lies underground between Interstate Highway 55, Demenil Place, and Cherokee Street. Construction along I-55 in the 1960s partially destroyed the cave, which was famous for its Lemp Brewery history and its rich, fossil-embedded sediments that contain ice-age animal remains.

Show cave development in the United States began with Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, which was first operated as a show cave in 1816. For the next 140 years, it became the model after which many privately owned show cave attractions were modeled. Even the given names of the features in Mammoth Cave have been widely copied by subsequent show cave developers.

Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, could easily be called the patron saint of the Missouri show cave industry. His book The Adventures of Tom Sawyer brought fame to Hannibal and the limestone cave just south of the city then known as McDowell’s Cave. In his book, Mark Twain calls it McDougal’s Cave, and the book’s success led to the cave’s commercial development. Mark Twain Cave was opened to the public in 1886 and, by contemporary definitions, became Missouri’s first official show cave.

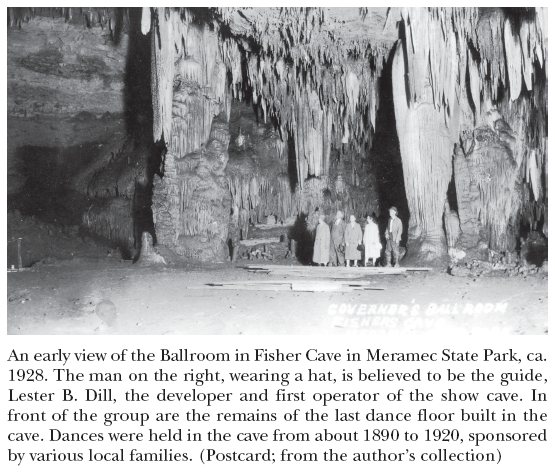

Between 1900 and 1929, twelve privately owned wild caves were developed and opened to the public.

Ancient Grotto, Cleveland Cave, Crystal Cave, Mt. Shira Cave, and Mushroom Cave were open to the public for only a short period of time. Fantastic Caverns was first operated as Temple Caverns. Talking Rocks Cavern began as Fairy Cave.

McDonald County saw an unusual wave of show cave development from 1915 to 1940 when J. A. “Dad” Truitt, known in his day as the “Caveman of the Ozarks,” was instrumental in opening a number of show caves in that county. In fact, the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s were important decades for show cave development all over America largely due to Truitt’s success in southwestern Missouri, the opening of Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico, the unusual circumstances of the death of Floyd Collins, who was hopelessly trapped in a Kentucky sand cave in 1925, and the international fame of Russell T. Neville. Neville was a pioneer cave photographer who shed light upon the beauty of caves to appreciative audiences throughout the world through public presentations of his work.

The stock market crash in October 1929 ushered in the Great Depression. One might think that, during the Depression years of the 1930s and the World War II years of the 1940s, very few caves would have been developed, but such was not the case. Between 1930 and 1949, Missouri saw the opening of at least eighteen new show caves.

Part of this surge was brought about by uncertainty about the future. The economic collapse was nationwide, but the privations of the Depression were not as severe in the Ozarks as they were in major metropolitan areas. Some people, however, saw turning a wild cave on their property into a show cave as a way of earning extra income and providing some additional financial security. Many of these developments were poorly planned, poorly financed, and involved caves that had very little to recommend them to the public as show caves. They were also opened before the state of Missouri established safety standards for show cave operations.

It should be noted that several of the show cave operations during this period were associated with resorts that offered additional attractions to the public, such as rental cabins and swimming, fishing, hunting, and other recreational opportunities. Under such circumstances, it was primarily the people who stayed at the resorts that visited the caves.

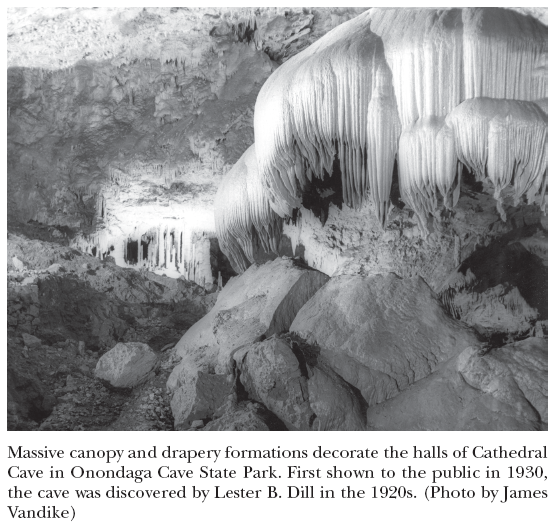

Cathedral Cave in Crawford County was originally opened as Missouri Caverns. Bunch Cave in Camden County was operated commercially for two seasons as Big Niangua Cave. Mystic River Cave at Ha Ha Tonka State Park is still open to visitors during a few weeks of the year but only as a wild cave adventure. Most of the year it is closed to protect an endangered bat colony.

The period 1950 to 1990 was the last great phase of show cave development in Missouri and gave the state fifteen new show caves, most of which are no longer open to the public.

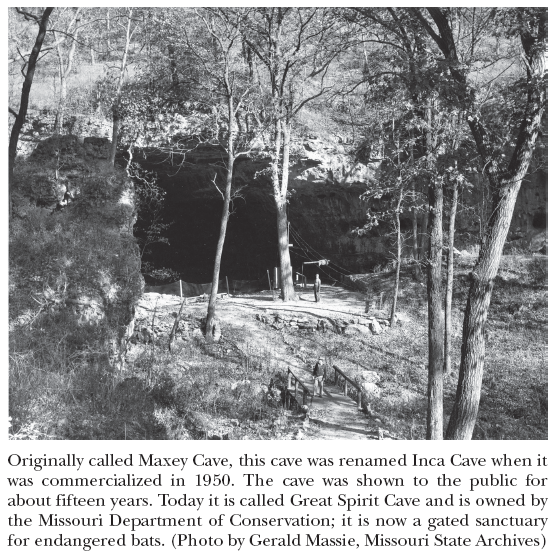

Stark Caverns is currently known as Fantasy World Caverns. Great Spirit Cave was opened to the public as Inca Cave. Indian Burial Cave was originally known as Big Mouth Cave. Ozark Caverns was opened to the public as Coakley Cave. Civil War Cave was originally called Smallin Cave and since being closed has regained its original name. Boone Cave has regained its original name of Rocheport Cave. Arrow Point Cave was originally known as Wright Cave. Emerald Grotto is better known as The Sinks. Emerald Lake Cave was originally called Martin Cave. Neongwah Bear Cave is generally referred to simply as Bear Cave. Onyx Mountain Caverns was originally Onyx Cave or Boiling Springs Cave.

With so many show caves being opened to the public, Missouri legislation was enacted in the 1950s charging the Missouri Division of Labor Standards with responsibility for giving each show cave an annual safety inspection. This inspection is designed to ensure that the cave is structurally sound and that all trails and man-made structures within the cave are safe for public use. Missouri show caves have an excellent safety record.

Until the 1960s, no government agency operated a show cave in Missouri. The creation of the Ozark National Scenic Riverways along the Current River transferred ownership of Round Spring Caverns, previously a privately owned show cave, to the National Park Service.

In the 1960s, the Missouri show cave industry also established its own trade organization, the Missouri Caves Association, which went a long way toward replacing fierce competition with friendly and beneficial cooperation. Early in Missouri show cave history, cave “advertising warfare” was not uncommon and even led to lawsuits when the show caves were close together or their visitors had to use the same state or county road to reach them. Today, the Missouri Cave Association is also allied with the show caves of Arkansas. Many of the show caves of both states are also members of the National Caves Association. There are more than two hundred show caves in the United States.

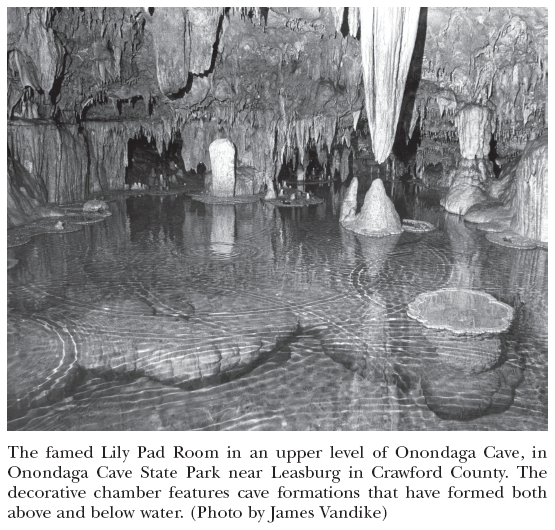

The Missouri Department of Natural Resources was established in 1974. Not long after, the department’s Division of State Parks acquired a number of properties for parks and historic sites, and some of them contained cave resources. Several caves that had been privately operated show caves then became state operations. These caves included Onondaga Cave, Cathedral Cave, Mystic River Cave, and Ozark Caverns, although Mystic River Cave, located in Ha Ha Tonka State Park in Camden County, was not continued as a show cave operation.

The first seventy years of the twentieth century was the golden age for Missouri show caves. Of the fifteen caves that have been developed since 1950, only three are still available to the public—Ozark Caverns, Devil’s Well, and Neongwah Bear Cave.

Devil’s Well in Shannon County is an oddity because the cave is not actually toured. Visitors simply stand on a viewing platform in the sinkhole entrance, where it is possible to see the gigantic, electrically lighted underground lake room a hundred feet below. Neongwah Bear Cave is a small secondary attraction in Camden County located along a nature trail in Thunder Mountain Park, which is owned by Bridal Cave near Camdenton. Bear Cave is available primarily to school groups and other organizations who are taken on nature walks along the trail.

Many factors have contributed to the conclusion of Missouri’s golden age of show cave development. The reasons are complex and numerous but include the construction of interstate and limited-access highways coupled with outdoor advertising restrictions and billboard regulations that went into effect in the 1970s. Billboards have generally become too expensive for most show cave operations to finance easily. Cave billboards currently in use are primarily those that existed before sign regulations came into effect and were grandfathered in when sign laws were passed.

In Missouri, show cave operators can now purchase several “directional signs” from the Missouri Highway Department. These small signs are erected on the state right-of-way near the cave’s turnoff by the highway department itself. They are important to a show cave operation because they give last-minute directional information for anyone already looking for a particular show cave. But it takes an interesting and compelling commercial billboard to inspire a traveler to pull off the highway and visit a show cave.

Most show caves cannot afford the daily newspaper, radio, or TV advertising necessary to be an effective medium for attracting substantial numbers of visitors to a remote cave location. Show cave operations have wasted millions of dollars over the years trying to find ways to advertise effectively using these media. In the end, it invariably comes down to having a good highway location, outdoor advertising, widely distributed and attractive brochures, and word-of-mouth publicity. If a visitor has been to the cave before and had an enjoyable and worthwhile experience, it is likely he or she will return and also influence others to visit the same attraction. The problem for the show cave is surviving long enough as a commercial venture to build a following of devoted fans. Federal- and state-owned show caves are subsidized by tax dollars; privately owned show caves are not.

The travel habits of the American public have also changed. Most travelers are not willing to leave the highways and drive several miles or more into a rural area to visit a single cave attraction that probably will not occupy them for more than an hour. They seek major recreational destination areas, and most show caves are not located in such areas where there is a captive audience. Grandeur, size, and historic value no longer guarantee a developer that his or her show cave will be a successful, long-lived commercial operation. Show caves are far more expensive to develop, promote, operate, and maintain today than ever before in Missouri show cave history.

It is interesting to note that of the six caves opened to the public before the year 1900, four of them are still in operation a century later, a success ratio considerably higher than for the other development periods.

Show caves have long been a major part of the backbone of Missouri tourism. Between 1900 and 1970, tens of millions of people visited Missouri show caves. At the height of show cave popularity in the 1950s and 1960s, summer travelers could depend upon finding more than two dozen show caves to visit in Missouri in any given year. Today, that number is considerably diminished, but more than half a million people still tour Missouri show caves each year, and as any fan of show caves will tell you, the Missouri landscape is just as beautiful beneath the surface as it is above.

For the privilege of getting to see these remarkable show caves of Missouri, we owe tribute to Missouri’s pioneer show cave men and women.