14

Cave Men and Cave Women

The beauty of Missouri is more than skin deep. . . . The state is as beautiful below the ground as it is above.

—MISSOURI TOURISM COMMISSION BOOKLET, 1972

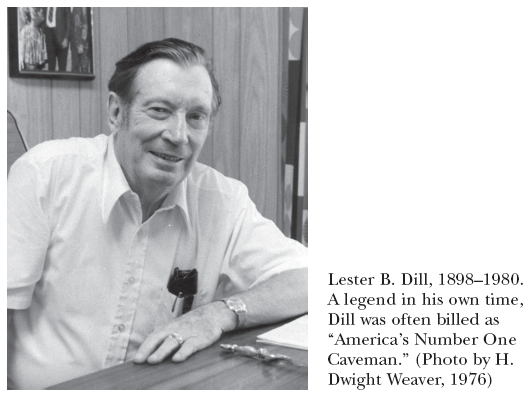

In 1966, the Franklin County Tribune ran bold headlines that announced “America’s Number One Caveman Is a Franklin County Resident.” The article featured Lester B. Dill, the owner of Meramec Caverns.

Dill grew up on a farm along the Meramec River on land that today is part of Meramec State Park. Many of the caves in the valley have large openings and spacious underground chambers where local people sponsored lavish cave parties during the summer months in the early 1900s. Cave exploring was nearly always a part of such social events. Dill and his brothers made pocket change by making themselves available as local caving guides.

Following the dedication of Meramec State Park in 1928, Dill’s father, Thomas Benton Dill, became the first park superintendent. By this time Les Dill was thirty years old. The Dills were able to convince the state to open Fisher Cave to the public as a special attraction in the park, and Les Dill operated the cave as a concessionaire. But in the early 1930s, when state politics changed, Thomas Benton Dill lost his position as superintendent, and Les Dill lost the cave concession. The younger man immediately launched a quest to find a nearby wild cave outside the state park that he could commercialize. He found just such a cave north of the park called Saltpeter Cave.

On May 1, 1933, Dill opened Saltpeter Cave to the public as Meramec Caverns. With the help of family he was able to transform the attraction into one of the greatest show caves Missouri has ever known. It is still one of the most popular show caves in the nation.

Missouri tourism history is enriched by the colorful stories of the pioneer show cave men and women of the closing years of the nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth century. Examples include the Cameron family of Mark Twain Cave; the Lynch family of Marvel Cave; the Powell family of Fairy Cave; the Mann family of Crystal Cave; the Truitt family of McDonald County; the Bradford family of Onondaga Cave; and the Dill family of Meramec Caverns. And it all began with Mark Twain.

In the 1870s and 1880s, a sequence of events occurred at Hannibal, Missouri, that changed the life of Evan T. Cameron, the son of John Cameron. John Cameron owned a dairy farm at the mouth of Cave Hollow, just south of town. In the same hollow was McDowell’s Cave, which had been used by Mark Twain as a setting for some of the adventures of his fictional character, Tom Sawyer, in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, published in 1876.

The Fielder and Stilwell families of Hannibal owned the cave. In the early 1880s, so many people wanted to see it that John East was hired to take people through the cave. His fee of ten cents per person was shared with the cave’s owners.

John Cameron’s son, Evan T., decided it was also a good opportunity for him to earn extra money. With his father’s blessing and the permission of the cave’s owners, he hung his own “cave guide” shingle in front of the Cameron home along the road leading to the cave. He charged twenty-five cents for adults and ten cents for children. The year was 1886. By this time, people were calling the attraction Mark Twain Cave.

In 1923, Evan T. Cameron, then fifty-eight years old and the operator of the family dairy farm, bought the cave property. Between 1886 and 1923, he had managed the cave operation for its various owners. During that time he had established a permanent tour route through the cave’s maze of passageways, built a small ticket building near the entrance, purchased lanterns that people could carry for lighting, hired cave guides, and advertised the attraction as Mark Twain Cave. The cave was open on a daily basis year-round.

Evan T. Cameron died in 1944 and was succeeded by his son, Archie K. Cameron, who was born in 1897 and raised in Cave Hollow. Like his father, Archie became a devotee of the cave. Following a hitch in the army during World War I, he returned home, married, and assumed management of the cave. Archie was at the helm of the operation for thirty-one years; he died in 1976.

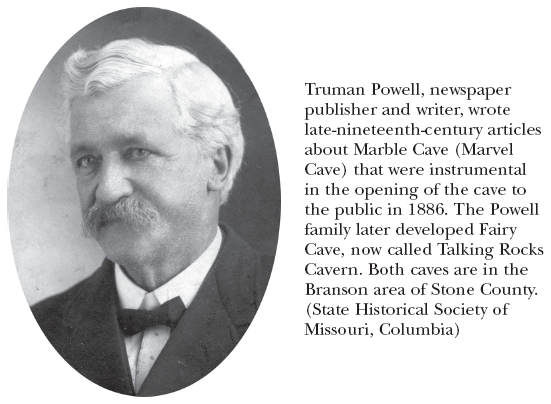

In the same year that Mark Twain Cave became Missouri’s first show cave (1886), the Truman Powell family moved from Lamar, Missouri, to the Ozarks and settled in Stone County. Truman Powell, the father of six sons, was a newspaper publisher and established the Stone County Oracle at Galena. Marble Cave (Marvel Cave) was just sixteen miles away. The cave fascinated Powell, and he began writing newspaper stories about it. Historians believe it was through one of Powell’s stories that William H. Lynch, a Canadian, heard about Marble Cave. He made a visit to the wilderness site and was so taken by the cave’s mystique that he bought it.

On October 18, 1894, the Lynch family opened Marble Cave to the public. Visitors entered by climbing down a long ladder into the gigantic, domed Cathedral Room, where a platform was built and a piano installed. William Lynch’s young daughters, Genevieve and Miriam, entertained visitors by playing the piano and singing opera tunes. The cave was so remote in those days that it had few visitors and proved unprofitable as a commercial venture. William Lynch, originally a dairyman by trade, closed the cave operation and returned to Canada, hoping to get back to the Ozarks when he had recouped his financial loses.

In his absence, Truman Powell’s son, William, settled near Marble Cave and began showing it to the public without the consent or knowledge of William Lynch. The Lynch family was gone for more than a decade, and the Powells thought they could claim the property through squatter’s rights, but when the Lynch family returned, William Lynch proved legal ownership and the Powells had to quit the property.

Not far from Marble Cave, on land adjacent to the homestead of Waldo Powell, was a cave of considerable beauty that the Powells had explored in 1896. It was small in comparison to Marble Cave, but they bought the cave property in 1907, named the new attraction Fairy Cave, and opened it to the public. Waldo Powell assumed management of the cave.

But Fairy Cave was not the sole domain of the men in the Powell family during their ownership. Miss Hazel Rowena Powell, a granddaughter of Truman Powell, also became a part of the Fairy Cave operation. Distinguished in her own right, her career included that of teacher, practical nurse, dressmaker, potter, lecturer, cave guide, and author. In 1953 she published Adventures Underground in the Caves of Missouri, a small guidebook to Missouri show caves. There were fourteen show caves in Missouri at that time, and her book was a milestone because it was the first book published that was devoted exclusively to Missouri caves. Fairy Cave was owned and operated by the Powell family until the 1970s, when it was purchased by the Herschend family of Silver Dollar City fame and was then renamed Talking Rocks Cavern.

After solving their dispute with the Powells over the ownership of Marble Cave, the Lynch family was determined to reopen Marble Cave and give the show cave business a second try. The Lynch sisters went back to playing the piano and singing for guests in the cave’s huge Cathedral Room. The stage built in the cave served many public events. William Lynch also built facilities on the property to house visitors and constructed a special road from Branson to the cave.

While their father busied himself with improving the property and attracting business, Genevieve and Miriam managed the cave, which is huge, deep, and extensive. The Lynch sisters became accomplished spelunkers and show cave operators. During their lifetime they were so devoted to the cave, its mysteries and its commercial operation, they had no time for suitors or marriage. But time found them. By 1950, their father had passed on and they were too old and frail to continue the work. By this time the name of the cave had been changed to Marvel Cave. They leased it to their good friends—Hugo and Mary Herschend and their sons Jack and Pete—who, as the years passed, carried the business to heights of greater success than William Henry Lynch would ever have dreamed possible. Thanks to the Herschends, Silver Dollar City, one of the nation’s oldest and most popular theme parks, was born on the mountain peak above Marvel Cave.

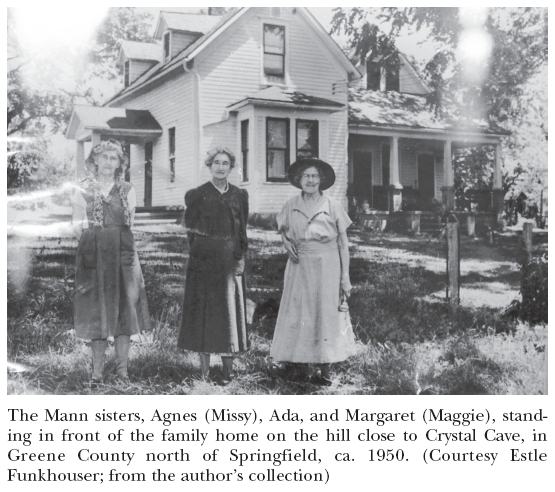

There were other “spinsters” in the Ozarks, as single women were known in those days, who were accomplished cave women. These women, the three Mann sisters, were in the hills just north of Springfield at Crystal Cave in Greene County. They, too, followed in the footsteps of their ambitious father, Alfred Mann, in the late 1800s and became a legend in their own time.

Crystal Cave opens in a small sinkhole on a gently sloping hillside. The cave consists of a complex series of highly decorated chambers. It was originally known as Jenkins Cave. Alfred Mann, a cabinetmaker by trade, came to the United States from England in 1870. In 1887, he purchased the Jenkins Cave property after seeing the cave. By the spring of 1893, Alfred Mann had the cave grounds cleared, a road put in, and trails constructed in the cave. He opened it to the public in the summer of 1893 as Crystal Cave.

Agnes (Missy), Ada, and Margaret (Maggie), Alfred’s daughters, were teenagers at this time. The oldest was eighteen, the youngest fourteen. They were bright, well-disciplined, lively girls, raised by a stern, demanding, religious father. As the years passed, the girls’ names became synonymous with Crystal Cave. People far and wide wondered why the Mann sisters never married and why they clung so steadfastly to the cave.

For the sisters, the problem was their father. Brilliant and educated though he was, he was also unyielding and domineering. Advancing age made him even worse. The dedicated efficiency of his daughters led him to the conviction that it was in the family’s best financial interests for his daughters to remain single and to continue managing the cave operation.

Only Missy, the oldest, made an effort to break away. For seven years she was courted by an ambitious young man, but in the end, he was driven away by Alfred Mann’s manipulative behavior. While the sisters managed the cave, their father managed them.

Alfred Mann died in 1925, followed by his wife in 1930. The Mann sisters continued with the cave. Missy, the first to pass on, died in 1960. Ada and Margaret, aging, surrounded themselves with animal companions. They had so many cats and dogs living with them in the old family home on the hill that only rarely did anyone choose to visit them. The cave’s business had declined, and if a visitor rang the bell by the cave to alert them at the house, the visitor would have to wait while one or the other of the two women hobbled down to the cave to guide the tour.

After the death of the Mann sisters, Estle Funkhouser, a retired Springfield schoolteacher, operated the cave for a number of years. Estle also had never married. She was an energetic lady and a delightful cave guide. She had known the Mann sisters quite well and had been their lifelong friend. Amazingly, the one suitor in Missy’s youth had been none other than Estle Funkhouser’s father!

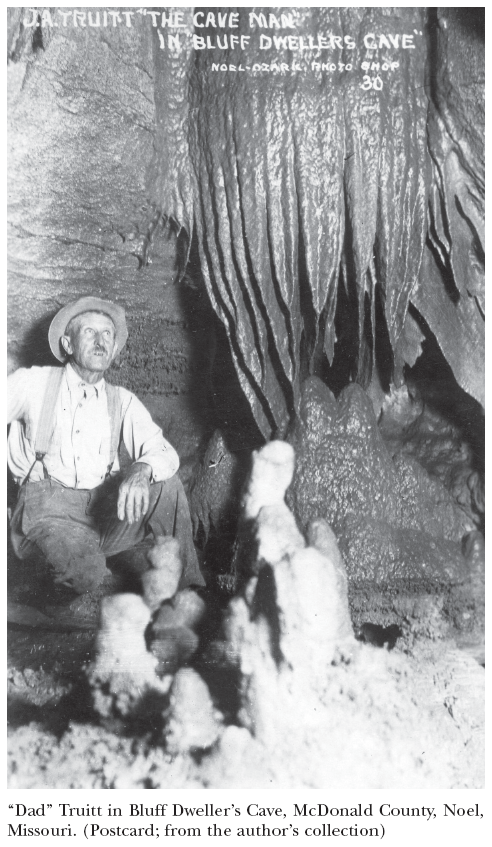

Marvel, Fairy, and Crystal caves are in southwest Missouri. Except for the northeast quarter of the state, where Mark Twain Cave is located, southwest Missouri was the cradle of show cave development between 1886 and 1926, after which much of the interest in developing show caves moved north and east into the heartland of the Ozarks. The last individual in southwest Missouri to officially lay claim to the title of “cave man” was J. A. Truitt, affectionately known as “Dad” Truitt.

Truitt was born in 1865 to Levi and Jane Truitt of Shelbyville, Illinois. He became a man of many trades when he reached adulthood. Before he and his wife, Lenah LaFaun, settled in McDonald County in 1915, he had tried several occupations, including that of farmer, streetcar conductor in St. Louis during the 1904 World’s Fair, salesman, and guide at Cave of the Winds in Colorado Springs, Colorado. When he and Lenah arrived at Elk Springs, Missouri, in 1914, they bought a resort along the Elk River and began making improvements.

Money was scarce. Dad Truitt worked at several jobs simultaneously in order to make ends meet while he struggled to revive the resort’s business. He wore such hats as mayor, justice of the peace, law officer, and depot agent. His need for cash was so demanding that he even searched for buried treasure in what little leisure time he had during the summer months. One summer, he found an opening in a bluff on his property that was exhaling a strong current of chilly air, a sure sign that a cave lay inside the hill. Dollar signs and visions of throngs of people coming to his Elk Springs Resort flashed before his eyes.

Truitt proceeded to enlarge the opening and explore the cave. He opened it to the public as Ozark Cave (later called Ozark Wonder Cave) in 1916. It became the first show cave in McDonald County. It was small, but well decorated, and while it was in no way comparable to Cave of the Winds for grandeur, it was a bonanza for Dad Truitt.

He was in the “Land of a Million Smiles,” where tourists and fishermen were abundant. Having no competition, his new show cave boomed with visitors. Dad Truitt had, in his own way, discovered the buried treasure he was looking for. Before long, newspapers as far as two hundred miles away were calling him the “Cave Man of the Ozarks.”

Dad Truitt turned his attention to other nearby locations where caves were rumored to be and began looking for a new cave to develop. Over the next forty years he would make his living selling real estate and opening show caves for himself and others in McDonald County. Truitt tried to transform more than half a dozen wild caves of McDonald County into show caves. He would develop a cave, promote it to get it going, then sell it and move on to a new site. For him, each cave was a new adventure.

When, decades earlier, Truitt had worked as a St. Louis streetcar conductor during the St. Louis World’s Fair, he may have learned about Onondaga Cave near Leasburg, Missouri, and it may have encouraged him to try the show cave business. Dad Truitt did not give up caves until he retired in the 1950s and moved to Sulphur Springs, Arkansas. He left behind a unique legacy in McDonald County, Missouri.

Farther northeast in the state in Crawford County another legacy was born in 1886 when Charlie Christopher discovered a cave while exploring a spring outlet near the Meramec River. He and his friend John P. Eaton attempted to open the cave to the public in 1897, calling it the “Mammoth Cave of Missouri.” Their venture was unsuccessful. They subsequently sold the cave to four St. Louis men, who established the Onondaga Mining Company. The company planned to mine the cave’s enormous onyx deposits for use in buildings to be constructed for the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

The mining venture failed. To recoup financial losses, the company made the cave available to World’s Fair visitors as a special attraction, calling it Onondaga Cave. Round-trip excursions to the cave were booked at the fair. Visitors made the eighty-mile one-way trip to Leasburg in Crawford County on the Frisco Railroad line. Once at Leasburg, a horse-drawn surrey called the Onondaga Cave Bus took them to the cave where they were given overnight lodging, good meals, and tours of the gigantic cave before their return trip to St. Louis.

After the World’s Fair, the cave remained open to the general public for regular daily tours, and Philip A. Franck managed the operation until 1913, when the cave was leased to Robert (Bob) E. and Mary C. Bradford of St. Louis. The lease contained an option to buy, and the Bradfords soon bought the cave. For the next thirty years, they shared the workload and an unexpected burden this cave brought to their lives.

At first the Bradfords prospered at Onondaga Cave in its Meramec River valley setting, but adjacent to the Onondaga Cave property was land owned by the Indian Creek Land Company. Boundary disputes erupted between the company and the Bradfords when it was discovered that Onondaga Cave’s commercial route ran beneath both properties. Costly lawsuits resulted, and the Bradfords lost in court, forcing them to cease using the portion of Onondaga that ran beneath Indian Creek Land Company property. It was a blow for the Bradfords, because that section of the cave was very desirable, consisting of a series of large chambers and passageways lavishly adorned with beautiful cave formations.

Matters only grew worse when Dr. William H. Mook, a renowned dermatologist associated with the Bernard Free Skin and Cancer Hospital of St. Louis, leased Indian Creek Land Company property over the cave and proceeded to open the section of Onondaga Cave that ran beneath that property, calling it Missouri Caverns. Fences were put up inside the gigantic cave to separate the two properties and the show cave operations. But even underground, the boundary was disputed. Rock throwing and verbal battles often took place along the fences between cave guides working for the companies.

To make matters worse for the Bradfords, the public had to travel a single road to reach both show caves. The road passed by the Missouri Caverns entrance before it reached the Onondaga Cave entrance, giving Missouri Caverns an unfair advantage. As a consequence, a bitter “cave war” erupted along the county road. Both operations employed people to lure visitors from the other’s attraction.

The cave war was not settled until after the deaths of both Bradford and Mook, when Charles Rice of St. Louis formed the Crawford County Caverns Association and leased both properties. After Rice died in 1949, the two caves were sold to Lester B. Dill and Lyman Riley at nearby Meramec Caverns. Lyman Riley assumed management of Onondaga Cave. The Missouri Caverns section was reunited with the Onondaga Cave tour route, and the entrance to Missouri Caverns was closed.

In the 1960s, a new threat to Onondaga Cave loomed on the horizon: the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers plan to dam the Meramec River for flood control and recreation. If built, the Meramec Dam reservoir would inundate much of Onondaga Cave as well as many other caves in the Meramec River valley.

A media and political battle was waged to defeat government plans to build the dam, and flames were fanned by sensational and often misleading news stories. Environmentalists, cave enthusiasts, sportsmen, conservationists, engineers, journalists, businessmen, citizens, and politicians all chose sides and locked horns. In the end, the plan to build the Meramec Dam was defeated by a vote of the people who had the most of lose if the dam were to be built—residents of the counties who would feel the greatest impact of the dam and reservoir, and landowners of the valley.

Lester B. Dill had become the sole owner of Onondaga Cave by this time. Because of the majestic nature of Onondaga Cave, the richness of its history, and his desire to see the cave placed in a position where it would never again be threatened by the schemes of men, he wanted to see the cave become a state park. Unfortunately, his death intervened in 1980. Dill’s estate, the Nature Conservancy, and the Missouri legislature then worked together to preserve Onondaga Cave for future generations. Onondaga Cave State Park was dedicated in 1982.

The pioneer show cave men and women of Missouri were among the forerunners who heralded a new attitude among Missourians about the value and significance of the state’s wonderful cave resources.