PREFACE

From Ash to Buzzard to Counterfeit, Missouri’s varied noncommercial and commercial caves are as endless as the times; as changing as the scenery; as ageless as the Elephant Rocks. Some you have heard about and probably visited. The names and locations of others would come as a surprise to most. And some say there are as many as 350 recorded caves in the Show-Me State!

—Missouri News Magazine (Missouri Division of Resources and Development), 1957

Today, anyone with a computer and an Internet hookup can go online and within a few minutes learn more about half a dozen Missouri caves than was known about all the caves in the state fifty-five years ago. I know because when I was growing up I was hungry for such information and it simply didn’t exist. Neither did the home computer or the Internet.

My introduction to Missouri caves came in 1945 at the age of seven when my parents took me to see Mark Twain Cave at Hannibal. We lived at Hannibal for several years before moving to central Missouri. During those years my father got permission to take me on a spelunking (caving) trip into the undeveloped portions of Mark Twain Cave. We also got to explore Cameron Cave, which honeycombs the hill on the opposite side of the valley in which Mark Twain Cave is located.

To say that I became hooked on caves as a result of those adventures would be an understatement. Those cave trips were important because they filled me with a passion for cave exploration and study that became a large part of my life for the next fifty-five years.

But it wasn’t until I was old enough to get a driver’s license that I could really begin to try to quench my thirst for caves. My father took me caving only occasionally, but once I had a driver’s license and a car, I was off into the hills of central Missouri almost every weekend with my buddies, looking for caves. Caves seemed to be just about everywhere. My favorite areas were the sinkhole regions in Boone County, which are now Rock Bridge Memorial State Park and the Three Creeks Conservation Area. I developed my spelunking skills in two of central Missouri’s largest and most spectacular wild caves—the Devil’s Icebox and Hunter’s Cave.

From 1945 to 1955, I discovered that caves and the creatures that use them did not receive much respect from most adults in that day and age. They said caves were dark, wet, cold, muddy, worthless holes in the ground. Caves were full of bats, which many people feared and thought were better off dead than alive. Adults said caves were where you would find poisonous snakes lying in wait for you, where a person could get lost, and where the cave ceiling might collapse and bury you alive. Never mind that these impressions were, for the most part, untrue. Such beliefs were very common, and I certainly could not disprove them, because there seemed to be no reliable and easily obtained information on Missouri caves.

Many landowners who had caves on their property considered them a nuisance and liability instead of a valuable resource if they were not pretty enough to be show caves. Most of the owners had not even thoroughly explored their own caves and either did not know or had forgotten how important caves were to their predecessors. Rumor held that every pit cave was bottomless and every wild cave connected with some other cave five or ten miles away. Meanwhile, the guides in show caves were more interested in entertaining visitors than providing useful information. Tour guides in show caves were long on legend and folklore and short on fact and reality.

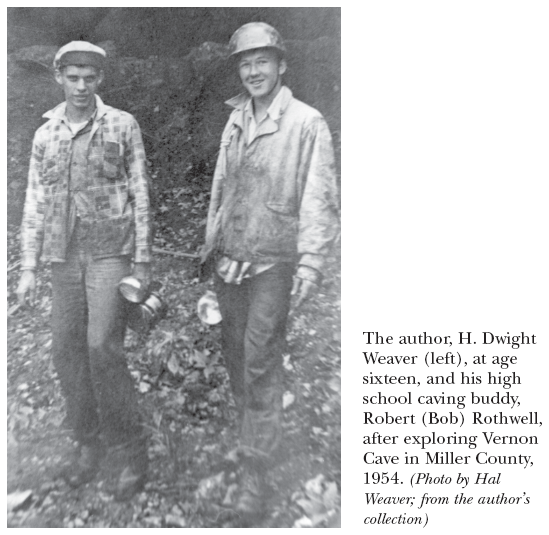

There were no caving clubs that I could join. There were no books on caves in any of the libraries that I frequented, and no books on caves available in local bookstores. I had endless questions and no answers. So at the age of sixteen, I vowed that since there were no books in the libraries on Missouri caves, I would write them myself. To begin my quest, I sat down and wrote a letter to every state that had a geological survey, requesting any information they might have on caves. I told them that I was doing cave research and was going to write a book.

In the following weeks I got letters and information from nearly two dozen state geological surveys and in the process made contact with the National Speleological Society (NSS). It was a relatively new organization dedicated to the exploration and study of caves. I had never heard of the NSS. I wasn’t quite old enough to join, but by 1956 I had become a member, and the NSS put me in touch with other members in Missouri. There weren’t very many, but they were in the process of establishing a statewide cave survey. I was fortunate to be in the right place at the right time to become a member of the newly formed Missouri Speleological Survey (MSS).

Thanks to the MSS and its dedicated member groups throughout the state who have spent the past five decades locating, naming, recording, mapping, photographing, and inventorying cave resources, Missouri now has one of the largest sets of cave files of any state in the nation. The archive is filled with reports on more than 6,200 caves, maps on nearly 3,000 of these caves, many photographs, and a great deal of miscellaneous information about Missouri caves statewide. These archives are housed with the records of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Land Survey at Rolla, Missouri.

I kept my promise to write those books. This one, Missouri Caves in History and Legend, is my sixth book on Missouri caves. Still, misinformation about Missouri caves is plentiful. What I have tried to do in this book is shed some light on the historical significance of Missouri caves and to explore the ways in which people in the past have both used and abused these resources. The expression “out of sight, out of mind” applies well to caves. Except for their entrances, their mysteries, wonders, and curiosities are cloaked in the eternal night of total darkness, and only a small number of people ever give them much serious thought. Half a century ago caves needed friends, because almost nobody understood them or really appreciated them. We’ve made a lot of progress since the 1950s. But even today, in what we like to think of as our enlightened society, our caves, the resources they contain, and the creatures that live in them still need friends.