THE FUNERAL interests me most. For it was the culmination of a life known by her admiring public wholly through the media.

Over a million people lined the route to pay homage as her cortege slowly wound its way from Kensington Palace to Westminster Abbey, where the church service began at eleven in the morning. Standing in silence, those crowding the edges of the road bowed their heads when the coffin, draped in a yellow and red standard and topped with white lilies, rolled past. Cameras craned above heads to snap photos of remembrance, tears were shed, prayers whispered. Above the hush could be heard only the clip-clop of the horses and the even rumbling of the carriage. Wheels grinded against stone pavements as horse, soldier, and mourner moved in a single dirge. The horses had been specially trained not to react to the bouquets of flowers thrown from the crowds. The faces of the soldiers were flexed and grim. Her two sons looked well bred and brave. As the cortege passed Buckingham, the royal family stood stone faced outside the palace gate, betraying nothing.

FIGURE 1.1 Princess of Wales’s funeral procession passing St. James Park. Photograph by Jialiang Gao, Wikipedia, public domain

An estimated 2.5 billion people watched on television. When the cortege turned toward the west door of Westminster it stopped, and gun carriage guards approached the coffin to lift and transport it into the church. BBC reporter Tom Fleming began to speak in a well-tempered baritone:

On a September day in 1982 I described the scene of the first official visit overseas of Diana, Princess of Wales. She was twenty-one and representing the queen at the funeral of a beautiful and much loved princess who had died some days before in a tragic car accident, Princess Grace of Monaco. Little did I imagine that fifteen years later to the month I would be watching the arrival of a simple coffin draped with another royal standard, bearing the body of that beautiful and much loved young princess of our own country, killed six days ago, in a tragic car accident.1

The guards raised the coffin from the carriage and solemnly transported it to a bier in the center of the abbey. Waiting for the service to begin, the camera again panned inside the church seeking personages. Some had already been shown arriving, including Diana’s natural mother—stiff, expressionless, just possibly sober. Now we saw her stepmother Raine, daughter of Barbara Carltand, who wrote over a hundred Romance novels reclining in the satin pillows of her pink couch, dictating chapter and verse to a bevy of secretaries. Margaret Thatcher was there, and Luciano Pavarotti, Donatella Versace, Richard Branson, a wide variety of people who had befriended the princess, those from TV and media who had been both friend and foe, patron and pursuer. In a gelato of language only the BBC could whip up, former secretary of state for health Virginia Bottomley was described as entering the church from “behind.” Then it was time for the service. The archbishop read, and one of Diana’s sisters, and Tony Blair. An aria from Verdi’s Requiem was sung. Elton John crooned Bernie Taupin’s lyrics, which had been rewritten from their original use in the Versace funeral for Diana’s, thus allowing the candle to burn in the wind at both ends of the Atlantic, and Diana’s funeral to become the Versace Requiem, “Deus ex machina.”

When Elton John finished his ballad a Monaco turn was made in the service and Charles, Earl of Spencer, Diana’s younger brother, rose to the podium to deliver the eulogy. The earl had flown up from Cape Town, South Africa, where he sows his wild oats in the same province as Mark Thatcher, son of Margaret. Mark was not at the funeral, perhaps because he was busy toppling some African kingdom with an AK-47 in one hand and his mother’s steel reinforced handbag in the other. The earl rose to his finest hour, speaking with passion and precision in a grieving but also celebratory voice, for his eulogy was of a life extinguished yet radiant. Beneath his pitch perfect accent the earl’s outrage at Diana’s treatment by the royal family was patent. He lambasted—without naming them—those royals who had driven his sister to her eating disorders and depressions. He pledged to protect her “beloved boys,” to do everything in his power to ensure they would not “suffer the anguish that used regularly to drive you to tearful despair.” He would seek to complete their education, to give them the experiences of life that would allow them to “sing openly, as you’d planned.” “We fully respect the heritage into which they have both been born,” he said, “but we, like you[, Diana], recognize the need for them to experience as many different aspects of life as possible to arm them spiritually and emotionally for the years ahead.”

When Charles turned to reminiscence his voice was the little brother’s, forever in love with his older sister:

The last time I saw Diana was on July 1, her birthday in London, when typically she was not taking time to celebrate her special day with friends but was guest of honour at a special charity fundraising evening. She sparkled, of course, but I would rather cherish the days I spent with her in March when she came to visit me and my children in our home in South Africa. I am proud of the fact that … we managed to contrive to stop the ever-present paparazzi from getting a single picture of her—that meant a lot to her.

These were days I will always treasure. It was as if we had been transported back to our childhood when we spent such an enormous amount of time together—the two youngest in the family. Fundamentally she had not changed at all from the big sister who mothered me as a baby, fought with me at school, and endured those long train journeys between our parents’ homes with me at weekends.

Intimate childhood bonds were invoked. But elsewhere the earl spoke of his sister in the language of an adoring fan, speaking to those millions of millions outside the church or glued to the telly. Charles’ language was starry-eyed, dazed at the mystery of transitions that had been the fabric of her existence, an existence he called “the most bizarrelike life imaginable after her childhood.” “The world,” he said, “cherished her for her vulnerability, while admiring her honesty.” It was as if she had created a public of vast intimates, each overcome by her unapproachable beauty, each simultaneously believing her their intimate. “For such was her extraordinary appeal that the tens of millions [2.5 billion] people taking part in this service all over the world via television and radio, who never actually met her, feel that they too lost someone close to them in the early hours of Sunday morning.”

Her troubles were of course the stuff of public knowledge and public sympathy—but not just her troubles, their expression, their very physiognomy. “Diana explained to me once,” he said, “that it was her innermost feelings of suffering that allowed her to connect with her constituency of the rejected.” Critical to that ability was her facial register of everything inside, her body posture, as if her physical incarnation were a mirror of her abundance of feelings, the tide of vulnerabilities she was wholly unable to contain. In her face the story already publicly known could be read and reread. The nerve endings and musculature of her sculpted cheeks, lips, and jaw were a living script, not simply a thing of classical beauty. Only a few actors and actresses have this natural ability, this expressive physiognomy. Anna Magnani had it, and Edith Piaf, and perhaps Marilyn Monroe. They could croon without makeup, and one always felt the spontaneity of the genuine in their gestures. People therefore believed: believed without doubting.

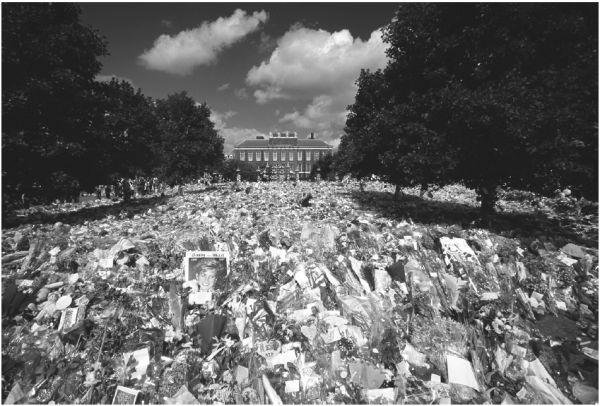

FIGURE 1.2 Flower bouquets for the late Princess Diana. Photograph by Ralf-Finn Hestoft, Corbis

The camera has always tracked physiognomy, something Erwin Panofsky already understood back in 1934.2 Jimmy Stewart’s twitch, Gary Cooper’s tight-lipped jaw, John Wayne’s swagger, Meryl Streep’s melting smile: these are what speak cinematic volumes, bring home and personalize larger narratives. Human physiognomy is the sculpture of the screen, its visual aria. Her tune was that of a blonde, Grecian beauty whose thin (underweight) fragility allowed pain to contort it at the slightest pressure without burying the flame in the eyes, the candle in the wind. Hers was a face that one felt was tuned to every register of emotion. Seeing was, in her case, believing, since her body seemed incapable of deliberation, therefore of deception. She was an actor, yes, played the role of royal on a million occasions, demurred dutifully, held her tea with the right form of expression, sipped and smiled. And yet the façade of royalty, also part of her, never fully erased the body’s own language. This was the source of her “integrity,” her ability, as in a film actor, to inspire conviction in a willing audience (of billions). Diana’s voice was tight, slow, without a great deal of lilt, lacking in wit. She never quite got things, shared the silent film comedian’s sense of world strangeness. The voice was part of the physiognomy of her suffering: stuttering, uncertain, with a hint of deadness. This added to her so-called genuineness and was read as further evidence of her integrity. Magical it was indeed that by simply crying without prompting at the presence of AIDS babies or victims of land mines she could get the world to say she was another Mother Teresa. Mother Teresa had spend her entire adult life caring, day in and day out, for the poorest and the dying in Calcutta, enduring heat and stench and pain and difficulties of all kinds without complaint, and here is a woman who gets off a plane, shows up before a thousand cameras, reaches into the dirt and utters in a quiet, shaking voice that land mines are a terrible thing, and the world jolts. All she had to do was be there and emote: before the camera. Christian to the core, her “morality” was read directly from her passion, from her pain at the world. Thus did she excite ancient desires for religion in a vast public caught in modern life. Max Weber called it the “charismatic personality.”

Diana’s empathy for those who suffered extreme pain was vital and unrehearsed. Nelson Mandela said it in an introduction to Diana: The Portrait,3 put out by the Princess of Wales Foundation (all proceeds to her charitable causes):

When she stroked the limbs of someone with leprosy, she did more to break the taboos surrounding that disease than any number of books, articles and health education programmes. When she sat on the bed of a man with HIV/AIDS, held his hand and chatted to him naturally as a fellow human being, she struck a tremendous blow against the stigma and superstition which can cause almost as much suffering as the disease itself.4

Her naturalness on the TV and with HIV/AIDS sufferers confirmed that she walked among us while being more than us. “We cannot all be a famous British Princess,” Mandela continued. “We can, however, all try to do what we can to insist that every human being is precious and unique.” This identification with her was a matter of her own ability to convert personal suffering into gestures of sympathetic identification with others. The public read her that way, as a figure who invited identification of their own suffering with her own.

The pain went way back, to the fate of a girl born one year after her parent’s second child, who lived only a few hours. Diana was meant to replace the child loss, but did not and could not. They’d wanted a boy. She always knew herself to be a bitter disappointment in a way that must have happened before her ability to speak and must have haunted her language centers like a torpid ghost. Mothers in mourning for lost children, mothering the new ones in alcoholic distraction, furious, perhaps, abstracted, the burden Vincent Van Gogh felt, and Gertrude Stein, and many others who were born to replace the irreplaceable, repair the irreparable. Diana had a heaviness not true of her younger brother Charles (a boy, and born later). This made her natural joy more sparkling, because more transient and more deeply felt. And it made her a person living in need of grace. Her ability to give it was felt by her public to be related to her need for it. This conversion of suffering into cure was, amazingly, something that came across through tabloid and TV. She was thus marked with grace, fated to carry a saintly aura.

From a British Film Institute book, based on survey research into the Diana phenomenon, here are two reactions to her death:

I did not have a happy childhood myself and, like her, I have sometimes felt out of control in the past as I’ve worked my way through various traumas to reach the point I’m at now…. I feel a certain respect for Princess Diana that she managed to hang on with gritted teeth almost and deliver a substantial amount of good despite her own difficulties.

And,

I was devastated [by her death]. She was a very special member of the Royal Family and reminded me of so much of myself. I too had a loveless marriage—I felt so deeply sad inside but never showed it to others. I tried to be happy, I too suffered an eating disorder because I was so dreadfully unhappy. Deep down I was crying out for help but no one understood. My husband said I was seeking attention and had no sympathy.5

A concept of Richard Dyer’s about the film star is useful here. Dyer writes:

The phenomenon of audience/star identification may yet be the crucial aspect of the placing of the audience in relation to a character. The “truth” about a character’s personality and the feelings which it evokes may be determined by what the reader takes to be the truth about the person of the star playing the part.

Treated as victim of her own position, and therefore one among the multitude of suffering congregants, she was vivified as saint. She could only have taken on this role because of what Richard Dyer calls her “star image.”6 This was a combination of feeling and physiognomy, of royal background and natural beauty. In our time persona carries moral authority, just as the voice of the newscaster is increasingly the grounds for believing what he or she says about the world. Diana’s moral persuasiveness was a matter of public belief in her sincerity, and the key to this was her spontaneous physiognomy, her crying, bodily shudder, gesture of drawing a baby to her breast. I have little doubt that she was sincere. But, if one wants to ask how the media constructed her, part of the answer is that through the lens of the camera her physiognomy became the grounds for her sincerity and was raised to film star power. No one thought to ask if any of her gestures had been set up (for the camera, for example), if the babies had been planted, and so on. Everyone wanted to believe in the spontaneity.

Her electric physical communication combined with her verbal dumbness made her apt for the silent star image: and hers was at odds with the royal posture where silence bears the authority of exclusion, the power of command. Normally, star image precludes allegory, the reading of personal history as morality play. But in Diana’s case the opposite was true. In her anxious twitches, frozen silences, spontaneous gestures of sympathy, personality became parable. The royals hated her for her own body language and for this mantle of morality she wore. Act fatuously and carry a purse, stand dutifully above it all: this is the royal adage for women. Inside the purse there is gin in the flask, which can help. The men are free to consort with their consorts; the women are all stiff upper lip and inner fury. The queen hated Diana for her inability to remain in a woman’s usual state of dutiful emptiness or quiet desperation. This was a failure of royalty, of duty, of Englishness. Even Princess Margaret had towed the line! Royals should be seldom seen (except skiing in Gstaad) and known exactly never. She could not help but reveal herself; her story reflected in her face like a mirror; her body was knowledge incarnate.

A recent film (Queen, 2006, directed by Stephen Frears) reminds us just how cloistered the British royalty had become after the Second World War, how out of date were their frozen demeanors, how disliked for their duplicity, how arrogant were their refusals of public presence. The Queen Mum had been hugely loved for her steadfastness during the London blitz; she drank her way through the bombings yes, but in danger, in Buckingham Palace, in London with her people. Elizabeth was cold, Philip off at polo in the Argentine, neither able to satisfy the public’s desire for a cult of royalty. Charles was a schlemiel and a philanderer, a man who would not or could not play by the rules: either give up your consort when you marry or keep the wife in tow. “There were two Dianas,” Charles announces in that film, the private Diana and the public, implying that the private was everything the public was not, unbearable, insufferable, a burden. No doubt rationalization, but Charles’s remark is also true insofar as the public’s Diana was an artifact of the media, known only through it. And she, “The People’s Princess,” the one who, first since the war, had given the public what it wanted: a figure worthy of their desire of cultivation, that is, of cult. The film sets Diana apart from the others by showing her only in film clips, TV interviews, photos, contrasting sharply with the dowdy ordinariness of the queen.

And so Diana’s public held a stake in her life, wanting its outcome to go one way or another, waiting impatiently for the next episode. News of Diana from the tabloids, her ongoing story, left the public hanging. Every chapter was magnified, turned episodic in the manner of television. She embraced AIDS orphans over the TV, and it was read right back into her star image, enhancing the magical magnifying glass through which her next episode was read. A dispossessed star, seeking liberty, seeking solace in a cruel world, active, joyful, depleted, unable to eat: this was the stuff of the greatest show on earth. A soap opera is, after all, an opera, although usually not one with high-level diva stars. She was a star without being a diva, tracked in every episode of her life with the expectation of melodrama. This tracking of her life, episode by episode, is the aspiration of television, which holds an audience in suspension over the airwaves so they can’t wait for Sunday night or Monday noon to discover if Thorne is going to get married, Tiffany will adopt, or Tony Soprano will get whacked. Reality TV is a new generation of game show taking place on bikini islands covered in flowers and poisonous snakes. Diana’s life was the real Reality TV, that rare stuff of public obsession over a story that was not a setup (game of getting off the island or entering the secret maze) but really happening. Her story was one large reversal: royal now hounded, princess now outcast, purebred turned talk show confessor, woman scorned, then reborn with Middle Eastern nouveau riche playboy, about to start (what else!) a production company, Euro-princess cavorting with high-class Eurotrash, Euro-princess about to become high-class Eurotrash. There is no better daytime drama than reversals of fortune.

She pled her case through the media and before the public and was tracked by the paparazzi, hunted by a breed of journalists as vicious as the hounds the royals themselves kept. “It was an irony,” said the Earl of Spencer, that “a girl given the name of the ancient goddess of hunting was in the end the most hunted person of the modern age.” Hunted in her Mercedes, speeding away from the stalkarazzi at two hundred kilometers an hour through the tunnels of Paris, her driver drunk, with no police escort—it had been removed some time earlier by the royal family, which clearly wished to dispossess and not simply dethrone her. Journalism prizes the distant, the larger than life, the unassailable, demanding access and accountability, delivering image and judgment. And it prizes especially the star, wanting to revel in her presence, while also collapsing the distance between she and her public. Yellow journalism wants to manipulate, intervene, expose star as object of scandal, prove the politician a porno fiend, show life up as a soap opera, generate (after 911) terror by finding evidence of Al Qaeda in aspirins, freedom fries, and foreign Romance novels. These things, as Michael Moore has taught us, sell. Diana’s was the rare case where yellow journalism actually gave her life the sensational ending it wanted: a car wreck increasing news ratings by big percentages.

In turn she came to play the game, reluctantly but well. The silent goddess talked, about her eating disorders, her marriage, her children, her career. Charles, Earl of Spencer, was keenly aware of the flak she’d taken for pursuing this route. In lines from the penultimate version of his eulogy, which he deleted, he addressed the point: “To say she manipulated the media is to miss the point…. She had to defend her inner self by bowing to the juggernaut strength of the press occasionally.”7

Within this melodrama of hunted, huntress, exemplar, she remained, spoke Charles, the same “big sister who mothered me as a baby, fought with me at school and endured those long train journeys between our parents’ homes.” And yet he describes her in the language of a star, speaking in the plural as one among many. She was “the unique, the complex, the extraordinary and irreplaceable Diana whose beauty, both internal and external, will never be extinguished from our minds.”

Such was her extraordinary appeal [he earlier said] that the tens of millions of people [actually 2.5 billion] taking part in this service all over the world via television and radio who never actually met her, feel that they too lost someone close to them in the early hours of Sunday morning [September 1, 1997]. It is a more remarkable tribute to Diana than I can ever hope to offer here today.

In a more academic language Richard Johnson remarks on a similar thing:

Even in her death Diana bequeathed to others the opportunity to grieve for ungrieved bereavements of their own. Misrecognized by critics as manufactured or sentimental, this mourning [by the public, on the occasion of her death] was … [genuine] public grief and personal loss, magnified as much by the intimacy and extent of Diana’s social connections (face-to-face and mediated) as by modern … media.8

The word cult is not out of order for a woman who could generate this intimacy, gestate her “particular brand of magic.” The only thing absent from the story is an Andy Warhol to paint it in duplicate or triplicate, to canonize her in acrylic, make of her a Marilyn or a Jackie. When Tom Fleming spoke of Diana’s first overseas assignment, “representing the queen at the funeral of a beautiful and much loved princess who had died some days before in a tragic car accident,” and went on to say: “Little did I imagine that fifteen years later to the month I would be watching the arrival of a simple coffin draped with another royal standard, bearing the body of that beautiful and much loved young princess of our own country, killed six days ago, in a tragic car accident,” he was pointing to symmetry between these stories. Each seemed to mirror the other, as if, through some equally particular brand of magic, each had taken on the features of the other, virtually becoming it. Diana was no film star, yet she took on the mantle of that stardom before the camera. She was a woman who had never acted in a film, but seemed to carry the aura of the star through some special baptism. Grace was born of no royal blood, assuming the royal posture with fairy-tale perfection when she married Prince Rainier, and this because she was already queen of the cinema before going on to become princess of the five-star hotel and the gambling casino. She was goddess before becoming princess. Each had a face of the classical ice goddess, a face also more than human in its way, revealing deep passion, contentment, cunning in Grace’s case and moving desperation in Diana’s. Each lived in a world of seclusion and fast cars, away from the media and yet wholly of it. In each the distant mantle of royalty blended with the distant mantle of the film star. These are also the stories of Marilyn and Jackie, those of a particular genre. Half fairy tale/half woman-on-the-verge melodrama, these beings exist between real life and the netherworld of the camera and in death become radiant icons in the museum of the public’s imagination. Diana takes on the attributes of Grace (movie stardom), and Grace Diana (royalty, pedigree). Diana’s Grace and Grace’s Diana.

This is our world, the world of Marilyn on-screen forever, Sugar dazzling in a tight skirt, spontaneous before the camera, good for the shareholders, funny, vulnerable, sunk in passion for saxophone players, bursting with soft, Veronese fleshiness, her torso a jazz riff, her eyes pools of light. And the world of Marilyn off, screaming in quiet desperation, swallowing the pills and not making it to the telephone. Billy Wilder had to do over a hundred takes of the scene on the yacht where she tries to “cure” Tony Curtis of his “ailment,” and she barely made it without collapse: neurotic, desperate, consumed with insecurity, always about to freak. She left the bulk of her estate to her therapist (to pay for the sessions she’s missed on account of being dead?), nothing but memories for her glamorous, loving, impossible husbands. A persona, a set of films, an iconic existence continuing beyond death, made alive through it: this gift for her public, a gift largely not of her own making.

Then there is Jackie with her Camelot existence, the assassination, the indelible image (John-John in his sailor suit, bidding his father goodbye), the presidential funeral—so drenched in media that she seemed permanently suspended between life and art. Surrounded by glitterati and Eurotrash, needing to get away from the ironclad grip of the Kennedy clan, Jackie resolved to raise her children abroad, to find another life, which she did on a yacht in designer swimsuits and elliptical sunglasses to the detriment of a real diva (Callas) and another melodrama with another death. She lived the second half of her nine lives at couture runways, hidden from journalists, in pursuit and in countersuit, filing lawsuits to retain privacy, becoming a businesswoman in New York. But, wherever she went, Jackie had orchestrated the presidential funeral and remained permanently within it, as if her life went on but also carried the aura of that moment in the form of a media halo. It haunted her, that halo in which she would always remain, laying the wreath on the coffin, forever in the public’s imagination, funeral and photo endlessly shown again, an icon that would never go away. It is hard to live in the present if you are also an icon suspended in time before the gaze of millions (within their gaze). Grace did not seem to mind the way the public projected her past onto her present, her film star status onto her queenly virtues. She seemed in love with the camera, assured in her narcissism. When she relinquished stardom for another life and transported its glamour onto a European stage, she was happy enough to be seen as a star in her new role in the casino royale of Monaco. Perhaps she didn’t care anymore.

These women lived lives as people and also as personages or icons. The personage was a thing largely uncreated by them. They existed here and elsewhere (there, in our imaginations, on screen, in the past, in the media bank, the aura of lost things). They found ways to accommodate this or were killed by it, depending. Whatever happened, it simply fed the public appetite for more of the persona.

The pairing of Grace and Diana is hardly one to have escaped notice, but, ironically, little has been written about it. The books I’ve read tend to be straightforward narratives, with a certain frisson of gossip thrown in for the “female reader.”9 The persona does not, of course, require any books. The night before I taped the Diana funeral from what was then my house in Durban, South Africa (her funeral was the third most watched media event in the history of South African television), I’d been busy screening Grace Kelly in Rear Window (1954, directed by Alfred Hitchcock), thinking about Liza’s remark about being studied “like a bug under glass.” Then the next morning the Diana funeral, the result of a butterfly trying to escape the glass.

Bugs and butterflies: the old studios (from the 1920s to the 1950s), understanding the public’s appetite for cannibalization, took it upon themselves to build up the star through a combination of withholding her and offering her to the public. The studios understood that too much publicity, too much viewing of insect under glass, will demean stardom by turning it into the daily fare of celebrity. The star in the old sense was about unapproachability. The theory was he or she should be present to the world primarily on-screen, not off. Such an exalted being is perforce also a celebrity, the result of film stardom and careful studio buildup. When he or she made an appearance at openings, charity balls, or was caught on film shopping the public gasped. Craving anecdote, scandal, images of ordinariness, the public, given free range, consumed the star, got closer and closer to her. What the studios grasped was that, unchecked, too much closeness would be a failure through victory, since the aura of her distance, which prompted the desire for intimacy, would be lessened, reducing her star value and producing final disappointment. Scandal can wreck a career, too much familiarity can make it prosaic. Given this, the familiarly craved by the public was provided an iota of satisfaction, which did fuel desire for more and keep the star in the public eye. This public, the studio understood, also did not want its stars to be people of ordinary life but, instead, filigrees of light. In this frame of mind the public desired proof of the star’s flesh-and-blood ordinariness, only to establish the mystery of transitions: the fact that stars are real people who appear in transformed form onscreen. Thus stardom existed in an uneasy relationship with the celebrity it also was, for the terms of stardom were in opposition to those of celebrity. Marilyn’s celebrity came in dribs and drabs: through what we knew of her marriages, through tabloid reports of her consistent failures (drugs, alcohol), through her notorious difficulty in the studio (finally she was fired from a film). But she became iconic mostly through her death. Had she gotten to the phone, her story would not have taken the turn it did, the melodrama would not have come to conclusion, the icon would not have properly formed before the public. These details of her life were enough to allow her melodrama considerable public attention, but she was also shielded, kept apart from her public, thus retaining star quality.

“The film star aura was … built on a dialectic of knowledge and mystery,” P. David Marshall writes. “The incomplete nature of the audience’s knowledge of any screen actor became the foundation on which film celebrity was constructed into an economic force.”10 My point is that this incomplete knowledge was also internal to the cinematic power of the star, internal to what made that person a star in film and maintained that aesthetic role. And so the older studio star was partly shielded from celebrity.

However, since the 1950s, with the ascendancy of television, stardom and celebrity have come to form a new alchemy. Even if the studio still existed as a machine of production, it would be unable to control television access to the day-to-day live coverage of the star. The star is someone given to us only through a particular kind of story (her films). She is distant (transcendent), her screen presence is inspirational and yet particular, detached from our lives. She exists mostly, perhaps exclusively for her public, through fiction. The celebrity is someone whose life is our interest. Television began in the 1960s to mass produce the star: “Star of the day, who shall it be?” began the theme song of Ted Mack’s Original Amateur Hour, as if every child with store-bought ruby slippers and a silver clip in the back of her hair could end up a Shirley Temple. This mass production divorced stardom from talent, not to mention that je ne sais quoi that is the peculiar, unrepeatable screen presence of each. Stardom then increasingly became an advertising concept, something attached to what is, in effect, celebrity.

Ironically, a media consumed with the raising of all things (all celebrity) to stardom is one that finally turns the star into a simulacrum. This was understood by Robert Musil in The Man Without Qualities with respect to the concept of genius. Ulrich, the novel’s main character, comes to realize that he can no longer think of himself as a “man of promise” when he reads an anecdote about a horse. Musil tells it like this:

The time had already begun when it became a habit to speak of geniuses of the football-field or the boxing ring, although to every ten or even more explorers, tenors and writers of genius that cropped up in the columns of the newspapers there was not, as yet, more than at the most one genius of a centre-half or one great tactician of the tennis court…. But just then it happened that Ulrich read somewhere … the phrase “the race-horse of genius.” It occurred in a report of a spectacular success in a race…. Ulrich, however, suddenly grasped the inevitable connection between his whole career and this genius among race-horses. For to the cavalry, of course, the horse has always been a sacred animal, and during his youthful days in the barracks Ulrich had hardly ever heard anything talked about except horses and women. That was what he had fled from in order to become a man of importance. And now … he was hailed on high by the horse, which had got there first.11

Such exaggerations of language are (perhaps) even more notoriously rampant in our own times, when Stephen Soderbergh’s film Kafka (1991) can be called “a mega-masterpiece” by one critic, as if being a mere masterpiece (like Kafka’s work itself) is no longer good enough for the terms of mass consumption. Genius increasingly becomes reduced to celebrity, and both become marketing adventures in the theater of presentations. So one ends up with the landscaper hired by my West Hollywood condominium association in the 1990s because he was “Tom Cruise’s gardener” (carrying the whiff of Tom Cruise’s celebrity by osmosis). This whiff was the criteria of excellence, the job reference. It is the stuff of Woody Allen’s Celebrity (1998), a mordant film about a New York now become Los Angeles where everyone bows down to the person who reads the weather on the local news channel because he too is part of television land.

In this world there is little place left for the aesthetics of the aura, of the film star.

David Gritten, a film writer and critic, says in a fine book that

the trappings of celebrity can look like a career structure in themselves. Young people, asked what they want to be as adults, sometimes reply, “Famous,” with not a single thought to what kind of endeavour it might be attached. And in fairness, why should they think differently? Ours is an age in which fame no longer necessarily depends on achievement; our TV screens, newspapers and magazines are filled as never before with people who seem famous just for being famous. (The American historian Daniel Boorstein first coined this idea: “A celebrity is a person who is well known for his well-knownness.”)12

Celebrities are well known for their own well-knownness: a provocative turn of phrase. The celebrity system runs on itself; the celebrity is valued in virtue of mere participation in the system. Put a slightly different way, celebrity is increasingly a media effect combined with public appetite. These together set its “market value.” Content becomes determined through the simple fact of participation in the relevant medium (television land). This wows the public. The medium is, in the famous phrase, the message. And it remains a message because the public is ready to accept it, like voting for a mannequin instead of a president. The media that provide the message are three: television, tabloid, talk radio. They are the pure form of commodity value, the system that sets the value celebrity. Celebrity is like money: a “currency” whose value waxes and wanes through these media forms. This is, of course, too simple, since many different factors generate celebrity, including talent. But it is more correct than one would like to admit. “We’re scouring every facet of American life for stars,” said People magazine editor Richard Stolley in 1977.13 “We haven’t changed the concept of the magazine. We’re just expanding the concept of ‘star.’”14 Most are talentless, without character, incapable of taking on any of the old—(dare I say it?) more profound and enthralling—aspects of stardom, lives with one-liner stories. Even in film the star is an increasingly absent phenomenon, while the celebrity actor multiplies. Her marriages, children, religious affiliation, sexual tastes, drug addictions, childhood abuse, infringements of the law appear daily on television and in the newsprint. Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt auctioning off the rights to the photo of their adopted baby in order to donate the proceeds to charity: these things point to lives lived for the television—and of it.

Celebrity is an expanding market, a robust economy. People magazine makes a person into a persona, whoever they are. In this system a person becomes a celebrity by being in constant circulation, and this circulation (being endlessly talked about, endlessly available on television) sets the celebrity value. It is destructive to the distance of the star, because her stardom depends on a modicum of public unavailability. She is simply out there too much and too often to retain the halo of the silver galaxy. Celebrity and stardom are, in contemporary life, largely at cross-purposes. This the old studios well understood.

What is unique from the point of view of aesthetics is the rare phenomenon in which stardom and celebrity alchemize, rather than their being in an antagonistic situation with celebrity often burying stardom. Diana’s stardom is not buried by her celebrity but complements it. She is, I think, new to history and extremely rare to it. Before her were Jackie and Marilyn and Grace. They are creatures of film, of television, and of media, whatever else they are. Their day-to-day goings-on are of the soap opera variety, while they continue to bear the hallmarks of transcendent, unapproachable stardom. Their aura is a unique one, reducing neither to film, nor television, nor any other single aspect. The celebrity market is a threat to the star icon, but her being out there in the media is also constitutive of her identity as a star icon because only through television and tabloid could her melodramatic life be watched and public absorption in it be created and maintained. How she retains the mantle of stardom while simultaneously living in soap opera TV and tabloid is one of the great mysteries. That she does is the subject of this book.

These star icons are fundamentally new in the history of aesthetics. Marie Antoinette had a cult flutter around her; Sarah Bernhardt was a star ne plus ultra. Queen Elizabeth, when young, was herself a media figure, her coronation watched by millions. The famous have their history, including a history of evolving means for becoming famous. What is new about Diana and company is the media and its cult of celebrity through which they rise.15 By the media is meant more than the tabloid papers (which have been around since the nineteenth century), but also film and television. Without a proper understanding of these—and, in the cases of Diana and Grace, royalty—the aesthetics of the icon cannot be grasped. These are aesthetics that transpose themselves onto the icon, graft onto her image. Diana never appeared in any film and yet carried the halo of film star—something, David Lubin has demonstrated, that already pertained to both Jack and Jackie during their time in official Camelot, and even at the moment of his assassination.16 Diana’s stardom is a portmanteau placed on her in the form of an aesthetic transfer in the public imagination from films to her. In her persona the distance of royalty, the classical beauty, the natural physiognomy allow her to become, in effect, Grace Kelly the film star, without ever having been on screen. Lady Di is perceived to carry the attributes of Grace Kelly, her screen presence, while Grace Kelly glides effortlessly from film stardom to princess of the realm, best in show, becoming the perfect royal, even if her kingdom was an ersatz one run on roulette. Diana’s stardom survives the television melodrama of her life, shines through it, lending it a special, aesthetic grace seldom if ever found in an actual television series. Each of these aspects (stardom, TV image, melodrama from life, royalty) harmonizes with the other, painting the whole in a particular, unreal cast. This is the mystery. Only a few have the right physiognomy, the right story, at the right time, with the right media attention, to simultaneously live in the glow of the film star (whether or not they have acted in movies) and the soap opera of television and tabloid. They seem to be created by that great casting agent in the sky, whose ways are ever opaque to the system, whose hand is invisible to the market.

I think this particular icon quality is, in our current world, vested mainly upon women: a feminized role demanding the quality of the star and the melodrama of a life lived passively, receptively, operatically, which is a gendered life. It is a role closely linked to concepts of hysteria and visual objectification. JFK was in his own way a kind of icon, for there are many kinds of icon, all with star quality matched by celebrity and an exemplary status of some kind. For some, John Wayne was an icon (exemplary of strong stride, tough masculinity, a slow drawl, and a decent conscience). He could do vulnerable, at least in love, at least with the camera of Howard Hawks leading him on. His icon status was as an indomitable settler, settler of land and argument. For others, Paul Robeson, big and wide as Wayne, football player turned lawyer, Old Man River rolling along as Communist, emperor (Jones) if not king, star in all things, never less than fully human, never free of the painful drama of black history, always battling the hand that wanted to keep him down, a prince among men. The younger generation has its own icons (Johnny Depp?). Of these varieties, the kind I describe is particular and seems to last in the public imagination beyond the others, for it is a kind that catapults the star into an even more distant galaxy of perfection by juxtaposing her stardom with the melodrama of her life. Some men approach the type: JFK had screen presence and star quality, cult following, and a load of trauma dogging him (the death of his older brother in the war, his intractable pain). And his assassination solidified his place in this particular firmament, although I think, it solidified Jackie’s place more. Were it not for the assassination, JFK’s icon status would have been different: in spite of the war and the load it made him carry on his back, the man was too happy, too conniving, too much in control of things, he was too much the Don Juan. His assassination brought the melodrama home. Elvis is perhaps the greatest male example of the kind of icon I’ve in mind: with an electrified physiognomy that hit from the belt and reverberated in the voice, a love of celebrity that was out of control and a gradual decomposition into drugs, isolation, a retinue of personal servants, physicians, and bad family relations that are the stuff of a Douglas Sirk film. He qualifies, I think, but if he does qualify it is because the melodrama had feminized him, because the bright colors and the acrylic hip hugging suits that bulged his masculinity also made him a woman, like he was overdressed for life and ready at the first glance to weep. This appliqué of femininity to the ultra male is a lip-syncing lipstick that sends gender haywire. Evidently a minimal condition for the icon is that he disrupt the canons of masculinity through his role as a figure of melodrama. To bring the point home: Lassie could be an icon, but not Rin Tin Tin.

A great deal has been written about the objectifying gaze of the cinema lens, which craves the study of stars like bugs under glass. It is systematically a projective gaze, in which femininity is vested onto the woman through the encaging lens of the camera.17 It probably remains true that women are as a whole less free, less idiomatic, less independent than men, which is why they’ve greater liability to the winds of fate and also a public readier to read their lives that way. The role demands this picture of liability, of being perpetually out of control, a woman on the verge. Moreover, this is a persona whom the public want to eat alive, at the same time preserving like the bug under glass, and such control over a being, even over her image, is, again, vested more completely when the image is that of a woman. The gaze “womanizes.” And so most icons of the melodramatic kind I’ve in mind here are women. The other side of this Madame Butterfly diva role is that we are profoundly sympathetic to the person in the female persona struggling to be a person, to the human drama of it all. Having imprisoned the dame in her gilded cage, we then seek to set her free. We find it moving to watch her live or die doing it.18