There Is Only One Star Icon (Except in a Warhol Picture)

AS ABSORBING as the Diana story is, this is not a “Diana” book. I was no part of the “Diana cult,” nor do I have any stake in praising or blaming her. I am not a British “subject,” nor am I a card-carrying member of any star society. To me the only true royals are the Marx Brothers—especially in A Night at the Opera, since I am a fan of opera, both comica and seria. That this silly, overbred, haunted girl became an icon before the masses is as unlikely as the Wagner opera Parsifal, which is so seria that it ends up comica, being the story of a pituitary case from the Rhineland who stumbles through his lobotomized life to become a hero and save a middle-aged Germanic cult from its blood and gore. This is interesting, since Parsifal is myth (although it did end up history around 1933), while Diana is the real thing (super-real given the role of the media in making Diana a figment of light). I am no fan of cults, finding them, like so many intellectuals on the left, deluded and dangerous. But I should also say I write as someone with a lifelong fascination. I find myself stunned by the star—a fixation I cannot get past. This comes from way back, a childhood watching movies home on a Sunday, eating TV dinners with my parents and brothers in a family that would, soon enough, generate its own brand of melodrama. My mother was always silent, deferential, glad to be of use; my father wept, wept before the old Hollywood movies replayed on television of Louis Pasteur (Paul Muni) fighting the French medical establishment, Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid) beckoning Ilsa Lund (Ingrid Bergman) to a life of comradeship without love because, even though she didn’t understand it yet (so said Richard Blaine, aka Humphrey Bogart), the problems of three people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. He wept because Charlotte Vale (Betty Davis) found romance on a cruise away from her crushing mother in the arms of the same Henreid (who evidently got around in high-class circles, but then he was a Viennese aristocrat). And he wept when the Morgan family emerged from the Welsh mines grimy in singsong because soon the valley would no longer be green, in spite of the good Walter Pidgeon. His was a boy’s world of heroes vanquished, mothers ever faithful, the new land ripe with invitation. At night he had dreams in which he was Atlas, holding up the world; his own mother’s brutally uncompromising voice weighing him down like an angry god. We all knew that the intensity of his emotion rose above its subject, as if he himself lived in the cinema screen, believing himself Gary Cooper walking down the streets of a deserted town at high noon, alone and afraid, his upper lip twitching, his eyes anxious and narrow, his courage that of a World War II veteran invading Omaha Beach. This knowledge made us uneasy, so that we were always looking to restore him to gaiety and ourselves to cheerfulness through some kind of play acting. We made movies, we three brothers, out of the stuff of Hollywood romance and acted them out for his benefit. His response would be to overwhelm us with tearful gratitude, which caused us the anxiety of children upon whom elders too much depend. My father was a man with a river for a soul and the boxing gloves of a John Garfield. You never quite knew if he was reciting Shakespeare or punching you out. He could be diabolical, sadistic, evil, but at these times we were touched, not infuriated. For me black and white still carries his tears; Kentucky Fried Chicken the taste of childhood. His contorted face was funny, and melancholy, and that Janus face is to me the face of the star icon. In the love of the stars my brothers and I bore was always hidden the melodrama that would later explode, causing each and every one of us to wrench in agony, like Diana before her “mam.” Oh, and I should add one thing: my father was a fashion designer. In our family what you wore was more important than how you felt. My mother dressed like a Barbie doll. She was her own kind of icon: cheerful, warm, plastic, sepulchral, powerless.

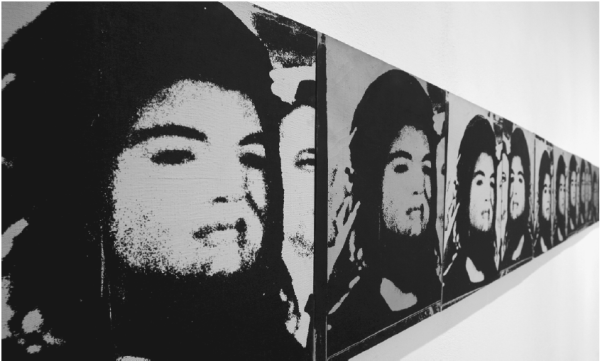

FIGURE 2.1 Andy Warhol, Jackie Frieze. Photograph by Justin Lane, Corbis

I am trying in this book to understand the icons I loved before I was old enough to grasp the force of this attraction, this pantomime drama. These icons captivated me in the way Shirley Temple captivated a different kind of person a generation before me, an immigrant boy from Pittsburgh with a talent the size of the silver screen, an artist who understood in his bones that with the icon melodrama is everywhere—and everywhere concealed (which is why it is melodrama). I mean Andy Warhol. Why not say it? I am totally ambivalent about this phenomenon, which is I think the way a lot of people feel about it. I write as a lover of this genre, but also someone incensed, repulsed, unable to sort out how this bizarre form took hold of an entire culture, convulsing it, convulsing me before I was old enough to be able to describe it. I believe I am in these respects an artifact of my times.

A number of books have already been written about film, television, tabloid, about star, celebrity, persona. There is a Diana industry out there ready to elevate, bury, and exhume the body and then bow down before it, extract every last drop of gossip, malfeasance, malady, or monstrousness in the name of pronouncing it “with us forever.” The latest book, by Tina Brown, is an acerbic and lucid story of life, love, and celebrity exhaustion, remaining within the circle of lunches-I-had-with-the-princess, who was, as always, the main course.1 The book has all the virtues and limitations of Brown’s old magazine Vanity Fair. As for the latest book about Grace Kelly, it is peppered with such scintillating and adept turns of phrase as “Accustomed to having his every whim fulfilled and buttressed by his million-dollar-a-month trust fund, Ricky di Portanova had always lived a gilded existence.”2 I hit rock bottom with a book comparing Princess Diana and Grace Kelly by someone who turns out to be a physical education teacher at a Florida high school. There is nothing wrong in that; one good physique deserves another. But on the back of the book the writer described himself as a devout Catholic with children and grandchildren, which I took to be his way of saying “Listen, Jack, I may be drawn to these babes, but a drag queen I ain’t. If you want to get physical, then let’s draw our guns now, bub” or words to that effect. There are scholarly books ready to claim that Diana didn’t exist at all, but was purely the artifact of the British tabloids (perhaps she really was a fortune-teller from the sixteenth century that the media dug up), others telling us that, while she was real, her audience’s feelings for her could not have been because they were mere constructs of the media (whatever that could possibly mean). Two things are clear: her audience loved her and they loved an artifact floating above, in the media, in their own imagination. How one sorts out the aesthetics of that is anybody’s guess.

Books on Diana have yet to focus on the aesthetic features of the media that composed her like a hair stylist, on the larger landscape of icon, aura, cult into which she appeared, on the doubleness of her being as person and floating opera directed by some on-the-job media conglomerate. Diana was the creation of a multiple aesthetic, the object of a divided public desire. She was marriage material for Charles because of her lineage; she became a public icon by virtue of her physiognomy, her story, and the culture of tabloid, television, film. She was a creature of film, television, tabloid, and consumer society as much as of royalty. Without the star system in its British incarnation, there could have been no Diana out there in the public eye. These elements conspired to generate public desire around her. Her public wanted her to live in the aura of transcendent unity (the royal/film star), but also wanted her life to remain rocky, unresolved, melodramatic so they could hang on for the next installment (the TV/tabloid goddess). The public saw her as inextinguishably radiant, while also in a state of semipermanent decomposition. They projected unreal perfection onto her image, then read her life story accordingly: sympathizing with her eating disorders and her self-inflicted pain, reveling in the whopping good story of her husband’s infidelities, remaining glued to the details of her divorce like viewers of The Truman Show (1998, directed by Peter Weir, screenplay by Andrew Niccol). They identified with her pain and with the grace they themselves vested her.

At the core of the Diana cult was this public ambivalence about grace. Her aura was seen to radiate it, but she was also loved because this aura eluded her. Cary Grant (who suffered depression) once remarked: Everybody wants to be Cary Grant; even I want to be Cary Grant. That he was from the English lower classes, one Archibald Leach, who arrived in Hollywood an acrobat from the stage to become Cary Grant in name, and in persona, while constantly eluding the aura of that personage in his own life, is a mirror of Diana. Except that it is not even clear she wanted to be the auratic being the public created, indeed it is not even clear she understood its terms.

Diana was a creature of trauma vested with transcendence, and the public’s ongoing desire for her to remain both is what distinguished her as an icon. As I’ve said before, icons differ from mere celebrities by virtue of their star quality—and from other stars by virtue of the way the public reads their star quality against the narrative of their life. I’ve said there are a number of varieties of icon, from the John Wayne type to the Mick Jagger can’t-get-no-satisfaction variety. All are tinged with star quality, celebrity driven and exemplary to a generation (although evidently not in the same way). These features make them icons of whatever type. The distinguishing feature of the Diana type is the doubleness of the persona: transcendent yet traumatized. She, the star icon, is an instance of the public’s desire for a world made whole through beauty. Theodor Adorno would say that modern times have dehumanized life to the point where the bounds of sense and evaluation have been burst: we can no longer find a way to speak, understand, evaluate what we have done to ourselves and become. There can be no poetry after Auschwitz, he famously remarked. Against this claim that authenticity consists in the refusal to speak, given the failure of language and the preposterousness of redemption (or even acknowledgment), the cult fixates on those whose raw terror can be made lyrical, rendered beautiful. This is a way of lying to the world about what is at its core, a similar lie to that which gives rise to religion. The aesthetic of the cult proclaims that redemption is possible even in the dregs of ongoing despair. Rather than acknowledge that suffering is waste, emptiness, lack of meaning, the cult turns to the suffering of the star icon, makes her aura into something transcendent, identifies with that transcendence, and thus practices a view of the world in which reconciliation with suffering becomes imaginable through her, in which the initiates’ own suffering becomes mysteriously elevated. Around Diana’s suffering, the public misrecognizes itself, as Jacques Lacan would put it, falling into the fantasy that its own lives are reflected in her halo and so its suffering is also, like hers, referred to beauty, made beautiful, redeemed. She lifts us up because she is brought down while remaining in our outer galaxy. Through misrecognizing ourselves in her we become transported above ourselves. This is the gaze of art that sublimes. Her aura allows for the misrecognition of wholeness, of reconciliation between suffering and beauty. Diana becomes for the public a sign of its own longing for grace, of its own image of grace already achieved and hovering above heads like a halo. The Diana identification is like a reconciliation with Christ screaming to death on the cross, which, rather than being abhorred as mere waste, cruelty or the sadistic politics of empire, is taken to be the sign that redemption for all is possible.

Trauma and transcendence. That picture of Diana, sitting in front of the Taj Mahal on the India trip, dejected, her head cast down, was a first sign of something seriously wrong. Diana was later obsessed with Mother Teresa, following her all around Europe, wanting to sit in her shadow, to become her. Diana, believing herself bereft of life, impoverished in every way, the poorest of the poor. When Diana appeared before her public haggard and emaciated, this excited public sympathy, but also the sympathetic nerve, allowing her public to refer its own pain to her beauty, misrecognizing themselves as similarly beautiful in suffering. She became their self-fantasy, the beautiful soul who catapults their own miseries into another, better realm.

This is dangerous enough, if also moving, since it is an attitude that ends up removing consciousness from recognition of the true nature of its suffering, not to mention the social injustice that partly gives rise to it. But there is an even deeper delusion built into the aura of purity and grace projected onto the fragile Diana. A refusal of the public to recognize its own sadism, its own desire for blood, melodrama, violence, to see that its wish is (at one level) that the Diana story never be resolved so that it can continue to enjoy this “weepie” on the telly. Secretly desiring reconciliation, they also desire more opera, they are a Roman public fixated with lust for death as the gladiators are about to fight—they can’t stop. The media generates this through its obsessive presentation of her, but public desire for execution, gore, blood certainly predated the making of television out of it, as any story of the history of public execution will tell. The public refuses to admit that the more Diana remains in search of a grace that eludes her, the more they like it.

And so around the cult icon (Diana) an ambivalent attitude toward her grace is played out.

Now most every form of celebrity is an object of some sort of public ambivalence: When a celeb goes off the rails, careening into dope, alcoholism, or a pedestrian, the public feels personally betrayed and genuinely outraged. How dare you do this to us, you who have everything on account of us? We shall pulverize you! As Leo Braudy puts it in his book on fame, “Modern fame is always compounded of the audience’s aspirations and its despair, its need to admire and to find a scapegoat for that need.”3 But this ambivalence is played out in a unique way for the star icon, whose very appeal consists in her combination of glow and pain. (Braudy’s book does not distinguish between types of contemporary celebrity, but is, rather, about the long history of the subject of fame, beginning in ancient Greece). This double interest in the glow and the pain is the source of the icon aesthetic, the Diana, Jackie, Marilyn, and, the Grace Kelly aesthetic. The star icon in general reveals the human in its range of characteristics: good, bad, ugly, desperate, fixated, blood lusty.

It is a glow and pain focused around the body of the star icon. Braudy puts it elegantly in a description he gives of Marilyn Monroe, whose life he calls

[a] virtual allegory of the performer’s alienation from the face and body that are nominally the instrument of her fame. Like the young Elizabeth Taylor, Monroe was both child and woman, to be nurtured and to be desired simultaneously. The sexual lushness she projected went hand-in-hand with the human impression of vulnerability. Wearing a body that was the object of the fantasies of countless others, she felt herself to be empty and so married two sensitive men: first Joe DiMaggio, the publicly certified athlete and gentleman; and second Arthur Miller, the publicly certified wise man and writer. But neither could fill the sense of incompleteness she had, which was as responsible for her public appeal as for her personal failure.4

Braudy ends this description with language close to my own: “If stars are saints, Garland and Monroe are clearly among the martyrs.”5 The genre is cult forming in the case of a Judy Garland and downright ecstatic in the case of a Diana.

It is a genre defined by these paradigm cases: Jackie, Marilyn, Grace, Diana, Judy et al. Some are actual film stars; others have this quality grafted onto them (by dint of Camelot and the like). There are intermediate cases between this genre and adjacent ones (JFK is an example, Elvis, I think, another, both of whom fall halfway into the star icon category and halfway into a more male/erotic type). My opening analytic move in this book depends on the intuition that these paradigm examples belong together, requiring a special kind of story. (If the reader does not share this sense he or she will probably find my book most unsatisfying, since this is for me a starting point I cannot otherwise prove than by trying to paint a picture of these dames that emphasizes what is distinctive about them considered as a gang.)

They live in Andy Warhol’s universe of the cult icon: a beautiful, cruel universe. Warhol’s work joyfully embalms the star while disposing her in flat indifference without aura. His work takes pleasure in her suffering (it is sadistic), but also deeply invested in her (it is empathetic). Above all, is it underexpressive, giving in to neither of these stances quite, instead projecting a deadened, bored, consumer stance toward the star, who is, after all, a mere item in the panoply of product images anyone can consume and, when finished, move on. Warhol’s early work from the 1960s dedicates itself to a small and elite collection: those few he recognizes as having icon value. Later he will become more interested, I think, in a department store of celebrity types from Chairman Mao to any rich New York collector who will pay him the 20K to have his portrait painted. In the early 1960s he confined himself to Jackie and Marilyn of the star icon variety, Elvis and Troy Donahue of the more masculine/erotic type. These are obsessively repeated.

Braudy points out that repetition is a source of the glow of fame: “Famous people glow … and it’s a glow that comes from the number of times we have seen the images of their faces, now superimposed on the living flesh before us—not a radiation of divinity but the feverish effect of repeated impacts of a face upon our eyes.”6 This is exactly right: repetition makes the image of fame glow. But the opposite is also true: image repetition dulls the glow, leading to current “Diana exhaustion,” past “Marilyn weariness,” the desire to change channels and change icons. It is this doubleness that makes the fate of the icon robust but also precarious.

Repetition also hides melodrama in the pseudo-mechanical forms it generates, as if the star icon’s image were hiding from the world in Warhol’s dark glasses—the dark glasses of a man who viewed the world from the safety of a moviegoer. Ours is a society where depth is continually converted into surface, emotion into consumer choice. Pain becomes Oprah-speak, illness choice of medication; mortification is staved off in the aerobic palace, destruction concealed through the excess of images that reveal it every day on the TV. Susan Sontag famously said that one photo acknowledges suffering while an endless parade of them deadens response to it. When Benetton can feature African AIDS victims in their ads as a way of selling jeans and T-shirts through “moral sympathy,” then the world runs on aura. Ad agencies could not have imagined running these campaigns were the public not ready to invest nearly anything with a halo and then go out and shop for it as if it were just another in an endless line of products. That these ads were pulled proves the public actually does have a moral limit somewhere, but it is pretty far out.

Diana is there to break through this Warhol consumerist indifference, but also to be consumed in exactly the same way. The life of the icon is an adulated life, but it is also life as a mere consumable. Like any consumable, her icon halo might at any point be reduced to mere image product; the public might decide it had consumed enough of her and trash her image or, more likely, let it recede into indifference after her fifteen minutes of stardom. Her sustainability as an icon is always at issue, under threat. In this she is different from the art in a museum or the violin concerto in a concert hall whose career has stood the test of time in bourgeois culture and is not, as yet, reducible to a consumer item, although the iPod may be doing just this. Diana was prevented the fate of immediate trashing because of her English status as royal, Marliyn because she remains to this day effervescent on film and because her death still satisfies public appetite for melodrama and has now become “iconic.” Grace Kelly only acted in five (near perfect) films; then became fairy-tale princess before the car spun out of control. Were Diana still alive, no longer royal (except in lineage), long away from Buckingham, married to Dodi Fayed and producing schlock movies in the production company they wanted to form, movies featuring the Spice Girls and Mr. Bend it like Beckham himself, were she a contestant on American Idol or Big Brother, a fixture at the ready-to-wear and your occasional falling-down drunk, she might have slipped from halo to another celebrity product, another has-been, another piece of designer Eurotrash. We cannot know what would have happened; we can only say that even the halo of the cult icon is fragile, given that it might at any point reduce in T-shirt value. This is part of what Warhol wanted to demonstrate about art—that a Brillo Box and a work of art are fungible, each so close in kind to the other that in our society the one might at any point reduce to the other because it already wears the other’s shoes—pertains to the aesthetic value of the cult icon. Warhol, in thinking he demonstrated this, proved the opposite, since his works of art are undoubtedly works of art rather than mere advertisements, or advertisements at all. Yes they are commodities whose value in commodity culture is that of image value. But their rarity is the rarity of Diana and Marilyn: that of a thing of beauty speaking melodrama and in many ways empty of content that is not yet reduced to Benetton.

It is worth noting that Warhol’s own epiphany about consumer society took place (according to him anyway) during a car trip he made in 1963 across country, from New York to his exhibition at the Pasadena Art Gallery (now the site of the Norton Simon Museum):

The farther west we drove, the more Pop everything looked on the highways. Suddenly we all felt like insiders because even though Pop was everywhere—that was the thing abut it, most people took it for granted, whereas we were dazzled by it—to us, it was the new Art. Once you “got” Pop, you could never see a sign the same way again. And once you thought Pop, you could never see America the same way again. The moment you label something, you take a step—I mean, you can never go back again to seeing it unlabeled. We were seeing the future and we knew it for sure. We saw people walking around it without knowing it, because they were still thinking in the past, in the references of the past. But all you had to do was know you were in the future, and that’s what put you there. They mystery was gone, but the amazement was just starting.7

What Warhol saw was a landscape of signage, a new American landscape where ad and celebrity ruled, rather than water, tree, and mountaintop. He loved the mind-numbing homogeneity of this culture where one thing increasingly becomes the same as all others by virtue of its sameness of circulation (as image). But his actual art focused (at least at the beginning) not on the mere celebrity, indistinct from all others who are well known for their well-knownness, but on the star whose star quality allowed her to become iconic. He was the Russian painter of religious icons for a world of Bloomingdales. His velvet was not that of the religious garment but the velvet underground, which he transubstantiated by embalming it as art. This stuff of images, the new form of American (and global) production, became the source, and the tomb, of the star, turning her (in the right melodramatic circumstances) into an icon. Her value was tripled: her own life, her place on screen or in the endlessly repeated historical moment, her recreation as image-icon by society and painter. This triple life could only have been made possible because of the movies, television, the tabloids, and because the art world shares Diana’s fate in crucial respects. Warhol understood this too: a work of art is not far from a star icon; the public desire and cult around it is critical to its commodity value. This conspiracy of art and marketing becomes thematic in Warhol, but is, we now know, the long result of the formation of the system of modern arts, which is a system where aesthetic values—of genius, innovation, depth of experience, aura, and the like—partly set commodity value, while, within the system, having the permanent liability to reduce to mere marketing formulas or logos.

Warhol made art when Picasso was old—old enough to have become the Picasso phenomenon written about by John Berger in The Success and Failure of Picasso.8 Picasso’s long-standing celebrity, the result of his appearance in a thousand newspapers, magazines, art journals, photo shoots, turned Picasso logo as he began to repeat himself, plate after plate, bowl after bowl, posing for the art photographer—bare chested with his piercing eyes, drawing in the sand for the camera, eating raw fish, living in neoclassical eternitty in the eyes of millions. Visiting him there was, one supposes, rather like visiting Grace Kelly as he churned out yet another south-of-France azure ceramic bowl or painting of night fishing. You got your two hours of genius on display and went home to publish it in the magazines. The genius of his endless innovation ended up in this assembly line of individual creations and endless poses, each reeking of the name PICASSO, so that the cardiologist or lawyer who read the magazine and then purchased the plate would be assured immediate recognition value for self and friends. This price of the Picasso object was set by the cult around his genius, the aura of the work, but also by the marketing logo of the product. With Picasso (and after) genius took on an aura beyond all commodity value and in so doing set the value of the commodity, the price of the assembly line of art items.

There is only one star icon; she is not repeatable; you cannot have an assembly line of mini-Dianas in the manner of a “minime” from The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999, directed by Jay Roach). Except in a Warhol picture, and this was his true genius: to realize that the life of the icon is one that celebrates and sustains the aura of the individual and multiplies her into something that has the permanent capacity to reduce her to self-logo, mere consumer item. The life of the contemporary artwork and the life of the icon have the same features. Both exist between aura (the aura of genius, the aura of stardom) and product. It was because Warhol recognized this in his own art and in the art world that he could similarly recognize it in the icon. That was, to my mind, his epiphany, his sense of who he himself was as artist and consumer.

These star icons are new and Warhol is new in the history of aesthetics because they have this life within media and consumer society. Their role is to break out of the consumer chain, generating deeper and more emotional cults, but also to turn back to the consumerist stance. This is new to history, I think. Marie Antoinette was a cult figure yes, but could not yet be a modern icon. It took the media in relation to late capitalism to transfigure cult figure into icon, to reestablish the terms of cult as focused on icon celebrities. And it took Jackson Pollock on the cover of Life, Picasso’s mug shot everywhere, to establish the cult of commodity as a cult maintained by aura and genius, transcendent stardom. It is the joint project of consumer society and the media associated with it to have produced the star icon or artist and his or her public in one fell swoop.

One should therefore not underestimate the stunning force of the art work of genius, or the star, in people’s lives—nor underestimate how quickly that turns into product value. Warhol had been stunned: stunned since he, the immigrant working-class closet gay boy sat in his working-class house in Pittsburgh awestruck by Shirley Temple, Ingrid Bergman, Cary Grant. We have felt the same, and also about a Picasso oil painting. We live with our stars like intimate friends and religious saints. Warhol once described his idea of happiness to be going to what was then the lunch counter downstairs at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, Oscars (in the 1960s) and ordering a soup and sandwich. You choose it, you eat it, it is gone, but it is the same soup you’ve eaten since childhood, mother’s milk, an experience of plenitude only knowable for someone who has eaten and adored the same thing since childhood. Repetition is not only about the conditions of reproducibility, the circulation of the image, the reduction of difference to homogeneity; it is also about an endless supply of things, a sense of their inexhaustibility. Films live forever, and there will always be Campbell’s, even if the size of the can has changed. And I don’t just mean new films, I mean Marilyn’s, which one never ceases to watch in amazement. These are our Campbell’s. And Warhol just as quickly realized that when you paint the star who has stunned you in duplicate and triplicate she flattens out into something you could (more or less) find in Bloomingdales.

It is this double life of the star icon that makes her so different from any mere celebrity, this double life of an art work that makes it so different from (more or less) everything else in Bloomingdales. Celebrity is something we know how to understand; it is a system of production with history and economy that, like all markets, expands and contracts until the mode of production falls into disarray and something else happens. And we understand commodities pretty well.

Icons are different. We do not know how to understand them. They dazzle and they stun like a stun gun. This aura, I have said, feeds into every aspect of their lives, including price. Warhol got it, was sent reeling by their allure, their diamantine power. Behind his dark glasses the man was permanently glassy-eyed. He’d been glassy-eyed (starstruck) since childhood. Warhol’s pictures are about their doubleness: on the one hand effervescent, beautiful, inexhaustible, on the other totally consumable, products among others in the department store of things bought and sold, circulated and collected. On the one hand amazing, cult forming; on the other something you can purchase and throw away. His pictures are expressive of both: they reduce icons to consumer products while being icon creating. And they are both consumer products and art icons. Philip Fisher, in a fascinating book,9 argued that Warhol’s work reconciles the industrial and inhuman with the handmade by celebrating “the factory,” while also inevitably carrying the personal stamp of Warhol’s “touch” (fato a mano). One might add that they reveal the art in advertising as well as the advertising in art, something a master of advertising art (Warhol in the late 1950s) turned fine artist (in the early 1960s) would know. Warhol’s quality of individual touch is also, explicitly, a marketing logo, a “product brand,” a self-marketing element. There is, nevertheless, something appealing in Fisher’s idea, for Warhol’s work is loved because it is unmistakably his hand, his touch, his way of doing things, largely unrepeatable by others. His work is itself iconic. This becomes its marketing logo, but also the thing about the work which astonishes. In Warhol individuality exists in a powerful, if also fragile, union. His work, both art and commodity, mirrors the status of the star icon.

And this is, I’ve tried to suggest, the truly stunning thing about the icon: that it also seems to unify a double life between aura and consumable. This is especially bizarre because the icon is neither person nor image but both—both in an incomprehensible collusion. The person’s life is folded into the icon, which then folds back into the life, transfiguring and disfiguring it. This is a relationship created of actor and star, which then jumps off screen to become living melodrama. There could be no icons without film stars, which means without the medium of film, because it is there where the audience attraction to the star is born (where the star is born), where the public receives instruction in the way stars are formed of actors, and actors of stars. But that is not enough: TV and talk show and tabloid enter the scene, and the marketplace of consumables, which allow the actor (Grace, Diana) to live lives in parallel: caught between their star quality and its temporality and their ongoing daily affairs. These two never reduce to one but rather braid, like a well-wrought hairdo, a wig or a noose, depending.

This braiding fulfills a deep desire of Romanticism: that life and art should become one, life thereby exalted, art thereby perpetual in life. This is Mozart’s dream of Don Giovanni, Giovanni’s dream, the dream of the Lebenskunstler, the artist who lives life like it is a work of art, making art of life. The sense of power, of omnipotence makes this a male fantasy. There is no room for the gap between desire and fulfillment to arise, nor place where imperfection might triumph. But if the dream of Romanticism is that of a life of complete power, both beautiful and sublime, of complete union (between person and art), the price of this braidedness for the icon is nearly complete powerlessness and to be caught in the abyss between her two lives. She is a passive entity in the formation of her persona: plagued by the halo around her self. That halo is the creation of the media and the audience desire channeled through it. Public desire hangs onto it, and her, forcing her into the position of recipient (if not bug under glass). She cannot exit, except by rushing off to Europe or slamming into the concrete side of a Paris tunnel. Her life is braided into an art she has in no way made, even if she has participated in its making, which she in no way controls. With the icon, the Romantic dream of power is transferred to the audience, which gets to create and enjoy her double life (between person and art/icon) and this is the vast aesthetic work of the media. Without a long look at that media, we will not be able to understand how the process works, nor appreciate its terror. With the icon the terms of power reverse. It is the public, rendered powerless in its mere voyeurism, that ends up controlling the icon—and through its own projective desire. The icon, who is given the power of the silver spoon, ends up caught in the spider’s web of the silver screen.

But there resides an irony: The icon figure is powerless before our gaze, but we, we are also powerless in our awe before it/her. As we shall see later, this double position of power and powerlessness is what film theory has understood to be the position of the film viewer watching the star on screen. It is a position Alfred Hitchcock revels in exploiting, a position his films are inevitably about. I am fascinated by a world in which everything powerful is in fact without power, a world of relinquishment. It is a dangerous, religious world, a world very close to idolatry. I am fascinated because I am a Jew grown up on the absolute rejection of idolatry. Thou shalt have no other gods before thee, only the one who shall not be made visible in the form of an icon. In our contemporary world everything seeks to be made visible, and visibility conveys price and power. And mutual powerlessness, because Diana’s viewers kneel before her and are powerless to change her life, while she can hardly get away.

The icon is as close to an idol as one can get.