FOURTEEN

Always Faithful: The PLA from 1949 to 1989

At the founding of the People's Republic of China on October 1,1949, the People's Liberation Army was 5.5 million strong. Its twenty years of experience in guerrilla fighting against both the Nationalists and Japanese had culminated in large-scale conventional operations during the Civil War. China's senior military leaders were also its senior political leaders and the army pledged its loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party above all. For the next forty years, China's enemies would change; the PLA's size, force structure, doctrine, equipment, and role in society would vary; and the balance between “red” (politics) and “expert” (professionalism) would be a constant source of tension within the PLA. However, in every test the Chinese military remained faithful to the Communist Party.

In the months prior to the establishment of the PRC, the PLA was basically an infantry-heavy ground force organized into five field armies:

The First Field Army led by Peng Dehuai operated in the northwest provinces of Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Ningxia.

The Second Field Army under the command of Liu Bocheng, with Deng Xiaoping as political commissar, operated in Henan, Hubei, and Anhui.

The Third Field Army commanded by Chen Yi operated in Shandong, Jiangsu, and parts of Anhui.

The Fourth Field Army under the command of Lin Biao first operated in Manchuria and then moved south into Hunan and Guangdong.

The Fifth Field Army commanded by Nie Rongzhen, with Xu Xiangqian as political commissar, fought in Hebei, Inner Mongolia, and parts of Shanxi.

The field armies were composed of numbered armies, each composed of several numbered corps. Over the next four years, the field army structure would dissolve, but the personal relationships among the leaders would remain influential for decades.

Mao Zedong was the chairman of the Military Affairs Committee (known later as the Central Military Commission, CMC) of the Chinese Communist Party's Central Committee, with Ye Jianying as vice chairman. Zhu De was named commander-in-chief, Peng Dehuai his deputy, Xu Xiangqian the first chief of the general staff, and Nie Rongzhen deputy chief of the general staff. Except for Mao, these leaders were professional, technically oriented officers.

Most senior military leaders also held high positions in the central government in Beijing, and many lower-level military leaders continued to perform the duties of civilian governance in China's six administrative regions as they did in the “liberated areas” during the Anti-Japanese War and the Civil War. From 1952 to 1954 most military officers were gradually relieved of their civil administration duties.

The earlíest elements of the PLA Navy were formed in the spring of 1949, and were composed mainly of ex-Nationalist ships and sailors; the leaders were former ground-force commanders. One of the navy's earliest leaders, Liu Huaqing, came to epitomize professionalism in the PLA. In the early 1950s, Liu served as the vice commandant of the First Naval Academy and then studied at the Voroshilov Naval Academy in the USSR. In the late 1960s he was deputy director of the Defense Science and Technology Commission under Nie Rongzhen, rose to command the PLA Navy in 1982, and ended his career as the most senior uniformed officer in the PLA.

The PLA Air Force was established in November 1949 and also was equipped with captured Nationalist and Japanese aircraft. Its first commander, Liu Yalou, had no aviation experience. He was assisted by Xiao Hua, considered one of the PLA's most effective political commissars.

“People's War” was China's basic military doctrine. As conceived by Mao Zedong, People's War was primarily a defensive strategy that relied on the mobilization of the Chinese people to make up for China's inferiority in weapons. It emphasized stealth, deception, and initiative. “Active defense,” which calls for taking the tactical offensive within a defensive strategy, was (and remains) a principal concept of People's War.

Until the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, the PLA's main mission was to complete its military victory over the Nationalists. However, China's final campaign against Chiang Kai-shek's forces was prevented by the presence of the U.S. Seventh Fleet in the Taiwan Strait immediately after the outbreak of hostilities on the Korean peninsula. Despite the fighting in Korea, the PLA was reduced in size to 3 million in early 1952.

ALLIANCE WITH THE USSR, CONFRONTATION WITH THE UNITED STATES

In February 1950, China and the Soviet Union signed a Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance. After about a year of fighting in Korea, the PLA began to receive massive infusions of military equipment from the USSR. When faced with superior firepower in the positional warfare that developed on the peninsula, the Chinese “volunteers” were forced to adopt much more conventional tactics than they had used in the first months of the war. After the cease-fire in 1953, the PLA reorganized using Soviet military organizational structures, doctrine, and tactics, and welcomed Soviet advisers and equipment. The USSR also provided plans and assistance for military factories so China could produce its own conventional weapons. The PLA instituted a Soviet-style system of military ranks in 1955, which Mao and many others in the party opposed because it shattered the PLA's tradition of equality among soldiers and leaders.

The Ministry of National Defense was formed in 1954 with Peng Dehuai as the first minister of defense. The experience of fighting U.N. forces in Korea led by the technologically advanced United States convinced the PLA leadership of the necessity of modernization and the importance of military professionalism. Long a proponent of professionalism within the PLA, Peng was just the man to lead the PLA down this road. However, many in the party preferred for the army to retain Mao's emphasis on revolutionary zeal and the supremacy of man over weapons. In particular, Peng made many enemies among the political commissars with his preference for “one-man command,” by which commanders held final authority in decision making over the commissars.

By 1956 thirteen Military Regions had been formed, placing the forces of one or more provinces under a single commander. PLA ground forces were organized into main force units that could be transferred from one part of the country to another, local or regional forces responsible for security only in their own limited locales, and militia forces that would provide manpower and logistics support to the main and local force units. Main force units were primarily the thirty-five infantry corps that had been part of the field army structure, as well as air and naval forces.

General military modernization was not paramount on Mao's national priority list in the mid-1950s. Mao believed that a protracted-war strategy, relying on China's size and manpower resources, was the proper response to the threat posed by the United States, which had signed a mutual defense treaty with Taiwan in 1954. The PLA was to be used for nonmilitary, economic functions, and to serve as a model for the rest of Chinese society. The best way to modernize the military was first to build a strong civilian industrial base. In a major policy speech in 1956, Mao stated that if the army wanted to build atomic bombs, then it should reallocate resources within its own military budget. In 1957, the PLA was reduced to about 2.4 million in a decision that would help limit the size of the defense budget.

Though he publicly denounced atomic weapons, Mao had actually decided that for both prestige purposes and military necessity China must have its own nuclear arsenal. At a meeting of the Politburo in January 1955, Mao declared that China would immediately begin a major effort to develop atomic energy for military purposes. Moscow also announced it would provide aid to China and several East European countries to “promote research into the peaceful uses of atomic energy.” Over the next three years, the USSR and China signed six accords related to the development of nuclear science, industry, and weapons. In the New Defense Technical Accord of 1957, the Soviet Union agreed to supply China with a prototype atomic bomb and missiles, as well as technical data.

In part, Mao was reacting to a threat from the United States, which at the time was developing the doctrine of massive nuclear retaliation to deal with an international Communist movement that increasingly challenged the “Free World” through military and revolutionary actions. In early 1953, the new Eisenhower administration had warned that it might use nuclear weapons to break the deadlock in negotiations at Panmunjom. Over the next five years, the United States also threatened China with nuclear strikes to gain leverage in the two Taiwan Strait crises over the Nationalist-held offshore islands of Quemoy and Matsu in 1954 and 1958; another such threat was the U.S. deployment of nuclear-capable Matador surface-to-surface missiles on Taiwan. Up until the 1958 crisis, Mao appeared to believe that the Soviet Union would provide China with a nuclear umbrella in the event of a confrontation with the United States. Moreover, he believed that the PRC could triumph in a nuclear war, even with the loss of millions of lives.

Nie Rongzhen was placed in charge of developing China's conventional military industry as well as its nuclear and missile programs. Zhang Aiping was given responsibility for research and development of conventional weapons and assigned to command the First Atomic Bomb Test Commission. Returned U.S.-trained scientist Qian Xuesen led China's missile program. Development of both nuclear weapons and surface-to-surface missiles was given high priority by both central and local governments through the assignment of highly trained personnel, allotment of funds, and access to resources such as land and material. A large assortment of commissions and ministries, including the Fifth Academy in charge of missiles and the Second Ministry of Machine Building for the nuclear program, were established to conduct research and build the equipment necessary for the bomb and missile programs. Though they encountered problems during the Great Leap Forward (1958–1960), when Mao attempted to mobilize the masses for economic development, these strategic programs received high-level attention and survived the political and economic turmoil China suffered in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Moscow did provide nuclear weapons expertise and a few surface-to-surface missiles to China, but it did not transfer a complete atomic bomb as it had pledged in 1957. Following the death of Stalin, the rise of Khrushchev, differences over grand strategies, and Russian perceptions of Chinese ingratitude led to a political rift between Moscow and Beijing. By early 1959, Khrushchev had decided China was an unreliable partner, a conclusion that paralleled the one Beijing had reached the previous year during the second Taiwan Strait crisis. As a result, over the next year all Soviet advisors returned to the USSR, many defense projects were left uncompleted, and much of the material originally promised to China was never delivered. At the same time, an important leadership change was taking place in Beijing.

Peng Dehuai was removed from his position as defense minister in 1959, mainly for his criticism of Mao's economic policies in the Great Leap Forward. His emphasis on military professionalism also contributed to his fall. Lin Biao, a well-respected commander who had been ill and relatively inactive in the mid-1950s, replaced Peng as defense minister. Lin's task was to reestablish the PLA's political and ideological foundation, as well as modernize the forces. Luo Ruiqing, a former political commissar, was named chief of the general staff.

Lin restored the balance between commander and political commissar. He reemphasized military training, yet allotted 30 to 40 percent of the PLA's time for political work. Lin also modified Mao's concept that “men are superior to material” by stating that “men and material form a unity with man as the leading factor.” This formulation opened the door for a strengthening of the PLA's more technical arms—the air force, the navy, and the soon-to-be-formed strategic missile force—while remaining ideologically safe.

On October 16, 1964, China exploded its first atomic bomb, developed on its own after the Soviet advisers had departed. Four months earlier China had tested its first indigenously designed missile, the Dong Feng 2 (DF-2). (Previously China had produced and deployed a few shorter-range missiles based on the Soviet SS-2.) The crash strategic program begun less than a decade before was a success. Immediately after its first nuclear test, Beijing announced that it would never be the first to use nuclear weapons and called for a conference to discuss their complete prohibition and destruction.

In the years that followed, a plan was implemented to develop an assortment of missiles with ranges that could reach U.S. bases in Japan, the Philippines, Guam, and the continental United States, as well as China's other regional neighbors. The Second Artillery Corps, China's strategic missile force, was established on July 1, 1966. A PLA Air Force bomber dropped China's first hydrogen bomb on June 17, 1967.

Over the next two decades, China produced and deployed approximately 150 strategic missiles of all types, though none with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), and an unknown number of atomic bombs to be delivered by aircraft. China first achieved the capability to strike the United States in August 1981 with the deployment of the DF-5 in hardened silos. China first successfully tested a submarinelaunched ballistic missile in 1982 and later deployed one submarine with twelve missiles. The relatively small number of single-warhead missiles with large circular error probable (i.e., low accuracy) indicated that China's nuclear missile force was a minimum deterrent force, capable of second strike, retaliatory, and countervalue strategic missions consistent with its declared “No First Use” policy.

REDEFINITION OF THE THREAT AND DOMESTIC INVOLVMENT

In the mid-1960s, Mao attempted to prepare China for an “early war, big war, and all-out nuclear war.” To protect China's strategic and conventional weapons industries from nuclear attack, he ordered a massive construction program in the interior provinces of Sichuan, Shaanxi, Guizhou, Hubei, and Yunnan. Industries in these areas were called the “Third Line.” Though they were relatively less vulnerable to attack, these factories were also far from markets and sources of raw materials; transportation and communications in these regions were poor, and educated, skilled workers were in short supply. Construction of Third Line industries continued through the end of the 1970s, but the problems of the Third Line plagued the defense industries well into the period of reform that followed.

During the 1960s, the PLA once again became an ideological model for Chinese society. Lei Feng, a selfless truck driver who died trying to help a comrade in trouble, was perhaps the most widely known model soldier. Mao wrote an inscription on Lei's “diary” (though the diary was actually a fraud created by PLA propagandists) and exhorted the country to “learn from the PLA.”

By the mid-1960s, Defense Minister Lin had also taken the lead in promoting radical Maoism to the point that the “red” versus “expert” argument was extrapolated into a struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie for control of the armed forces. According to the radical Maoists, politics was a prerequisite for technical expertise; technical training itself was of secondary importance. Disobedience of military orders could be condoned if subordinates believed that the orders given them did not conform to Mao's thought. Professionalism in the army was equated with “the bourgeois military line” and “Soviet revisionism.” In June 1965, military ranks were abolished to minimize the distinction between the military and society. Peng Dehuai and Luo Ruiqing, who was removed from his post as chief of the general staff in late 1965, were accused of promoting the “bourgeois military line” under the pretext of modernization.

Differences in strategic outlook had created a split between Lin Biao, who was soon to be designated as Mao's political heir, and his chief of the general staff, Luo Ruiqing. Their disagreements were based upon differing interpretations of the threat to China from the U.S. war in Vietnam and the proper response by the PLA. Luo advocated finding a way to bring China back under the Soviet Union's nuclear umbrella and, if necessary, conducting a defense of the mainland much closer to its borders by moving more quickly into an offensive, counterattack mode. Lin, on the other hand, stressed the necessity for China's self-sufficiency and adhered to Mao's classical strategy of “luring the enemy deep.” These differences led to Luo's greater emphasis on main force units, while the Maoists focused more attention on the local forces and militia in a People's War. Luo's challenge to Lin's military leadership and Mao's national policies resulted in his removal from office. Nevertheless, many of Luo's recommendations were later implemented by the PLA.

Lin's political rectification of the army prepared it for its role during the Cultural Revolution. The PLA initially was tasked to provide logistics and transportation support to the Red Guards as they held mass rallies in Beijing and traveled throughout China. But by the fall of 1966, the students' activities had begun to get out of hand and undermine the authority of party and government organizations. In the summer of 1967, radical Red Guard “rebels” attacked military headquarters in the city of Wuhan and other parts of China. As the chaos spread, the PLA was called upon to restore order; however, in the fighting that followed main force units and their local force brethren often backed rival Red Guard factions. Violence continued through the spring of 1968 until Beijing finally committed itself to ending the chaos. Military “Mao Zedong Thought and Propaganda Teams” and “Three Supports and Two Militaries Teams” were dispatched to exercise control in much of the country. In areas where the PLA could not form an alliance with remaining revolutionary cadres and the revolutionary masses, Military Control Committees were established to maintain order.

As a result of the need for the PLA to reestablish domestic tranquility, military leaders were reintroduced into both local and central government functions in numbers that had not been seen since the end of the Civil War. By 1971, military officers occupied approximately 50 percent of civilian central leadership positions and 60 to 70 percent of most provincial leadership jobs. The PLA also grew in size to over 4 million to cope with its domestic responsibilities during the Cultural Revolution. However, professional military training suffered immensely.

Not long after Lin and Luo were debating the degree of danger from the United States in Vietnam, a new threat began to emerge on China's northern border. In the mid-1960s, the Soviet Union increased its forces and logistics capabilities in the Far East. In 1967, the Soviet Union and the Mongolian People's Republic signed a mutual defense treaty and Soviet forces were stationed in Mongolia. In 1968, the USSR held large-scale military exercises in Mongolia and tensions between Moscow and Beijing rose. The decade-long ideological dispute between China and the USSR turned into a series of armed clashes along China's northeast and northwest borders in the spring and summer of 1969. Mao began to assess the Soviet Union as a greater threat to China at about the same time that U.S. president Richard Nixon began looking for a way out of Vietnam and a strategic partner to balance the Soviet threat to America.

Concurrently with Mao's strategic reevaluation, Defense Minster Lin began to voice contrary opinions. While Mao sought to withdraw the PLA from its civil governance responsibilities assumed during the Cultural Revolution, Lin advocated that it remain involved in local politics. He also opposed Mao's rapprochement with the United States as a balance against the Soviet Union. Rather, he believed that China's traditional “luring in deep” strategy would be sufficient to counter the Soviet mechanized forces growing on China's borders. By 1971, instead of being Mao's successor, Lin had become a challenger to Mao. Lin, his wife, and his son died in a plane crash in Mongolia in September 1971. Allegedly, he was attempting to escape to the Soviet Union after a coup he was plotting against Mao was uncovered.

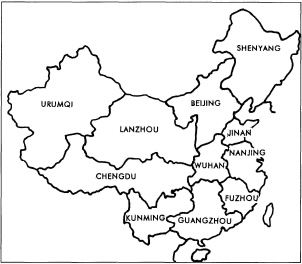

Map 14.1 Chinas military regions, 1970s. Adapted by Don Graff based upon From Muskets to Missiles, Harlan Jencks (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1982), p. 301, map G-l.

Map 14.2 Chinas military regions, 1990s. Adapted by Don Graff based upon The Armed Forces of China, You Ji (London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 1999), p. 48, figure 2.2.

In the aftermath of Lin's death, the general staff was purged of his supporters and the number of military officers in the party's Central Committee was cut in half. PLA units “returned to their barracks” and military officers in large part were removed from their duties in local governments. The reassignment of eight of the commanders of the eleven military regions (two of the original thirteen military regions having been reduced to provincial military districts in the late 1960s) in late 1973 and early 1974 was an important symbol of the PLA's exit from local politics.

TOWARD THE REBIRTH OF PROFESSIONALISM

Deng Xiaoping returned to the central leadership as a vice premier and member of the Politburo after having been “deprived of all posts” in 1966. In 1975, he became a vice chairman of the Central Military Commission and chief of the general staff. Premier Zhou Enlai proposed the “Four Modernizations” of agriculture, industry, defense, and science and technology. At an enlarged meeting of the CMC, Deng made a scathing criticism of “overstaffing, laxity, arrogance, extravagance, and indolence” within the PLA. The stage was set for a new era of military professionalism, but death and politics intervened once more.

Following Zhou's death in January 1976, Deng came under political attack from radical Maoists and was removed from all posts in April. Zhu De's death in July gave the new premier, Hua Guofeng, the opportunity to deliver Zhu's eulogy. In late July, the PLA redeemed the image that had been blemished in the Cultural Revolution during its rescue efforts following the Tangshan earthquake, which to many Chinese presaged the death of the emperor. Approximately six weeks later, Mao Zedong died.

Hua was able to consolidate his position with the help of Ye Jianying and Nie Rongzhen. Less than a month after Mao's death, Hua ordered Wang Dongxing, Mao's former bodyguard and commander of the PLA's 8341 Unit, an elite force responsible for protection of the central leadership, to arrest the radical “Gang of Four”: Zhang Chunqiao, Wang Hongwen, Yao Wenyuan, and Mao's wife Jiang Qing. Hua then became chairman of both the Party Central Committee and the CMC. In July 1977, Deng was rehabilitated again and reinstated to his government and military posts, including his membership in the CMC and his post as chief of the general staff.

Deng gradually became the most powerful leader in China, even though Hua officially held important titles for a few more years. The Third Plenum of the Communist Party's Eleventh Central Committee in December 1978 was the watershed event that redirected China's national focus to economic modernization. The Four Modernizations were adopted as national policy, and as this was done the ranking of defense modernization was slipped to last. This minor change basically meant that the PLA was tasked to modernize and professionalize, but it would be low on the list for government resources. Thus, military modernization became a long-term goal, dependent upon first strengthening the overall Chinese economy.

The United States's formal normalization of relations with China on January 1, 1979, strengthened Beijing's position in the U.S.-USSR-PRC triangle. The break in diplomatic relations between Washington and Taipei and the abrogation of the U.S.-Taiwan defense treaty, which were part of the normalization deal with the United States, also strengthened China's position vis-à-vis Taiwan. Beijing stopped the shelling of Quemoy and Matsu that had begun in 1958, proposed talks with Taiwan, and removed some PLA units from Fujian province directly across from Taiwan. However, increased Soviet aid to Vietnam, the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan all contributed to Beijing's perception of Moscow's efforts to encircle China.

Ostensibly in reaction to Vietnamese border incursions, the PLA launched a “counterattack” into northern Vietnam in February-March 1979. The PLA's tactical performance during this brief but bloody campaign revealed serious shortcomings in its doctrine, training, logistics, and equipment, and added further impetus for military modernization.

Thus, at the beginning of China's period of reform, a bloated PLA of over four million personnel was structured to defend the Chinese mainland using the doctrine of People's War. At the same time, the Soviet Union was increasing both its conventional and nuclear capabilities in the Far East opposite China.

The PLA was dominated by ground forces and had a definite continental orientation. Its main force units were organized around infantry corps, generally composed of three infantry divisions and smaller armor, artillery, engineer, and other combat support and combat service support units. Most equipment was of 1950s vintage. In theory, a large militia would provide logistical and some combat support to main and local force units as they “lured the enemy in deep” and drowned him in the vastness of continental China. Air and naval forces primarily had a defensive mission and, for the most part, operated independent of the ground forces. China's nuclear forces were small (compared to U.S. or Soviet strategic forces), structured for deterrence and, should deterrence fail, to conduct retaliatory strikes against population centers in the USSR.

The PLA had completed the process of “returning to the barracks” (i.e., removing itself from involvement in all aspects of civil society), and had subordinated its modernization to the larger task of national economic development. Except for a spike that resulted from the campaign against Vietnam, the low priority for military modernization translated directly into low defense budgets for the 1980s. The PLA was required to grow much of its own food, and produce in its factories many of the light industrial goods necessary for basic survival and mission accomplishment. The fact that the senior PLA leadership accepted its low priority in China's national modernization strategy is a reflection of its discipline and loyalty to the Communist Party and China's civilian leaders.

In June 1981, Deng Xiaoping replaced Hua Guofeng as chairman of the CMC. Hu Yaobang took Hua's position as party chairman. Deng began to fill senior positions in the military with officers loyal to him: Zhang Aiping was named defense minister, Yang Dezhi became chief of the general staff, Liu Huaqing assumed command of the PLA Navy, and Yang Shangkun was made secretary-general of the CMC. In 1982, the National Defense Industrial Office under the State Council was merged with the Defense Science and Technology Commission and the Science and Technology Equipment Committee of the CMC to form the Commission on Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense (COSTIND). COSTIND reported to both the CMC and State Council and was responsible for overseeing production in the defense industries and planning military research and development.

In another government reform, in accordance with the State Constitution of 1982, a State Central Military Commission, responsible to the National People's Congress, was established. This body was, in theory, different from its counterpart in the Communist Party structure, but in reality consisted of the same set of leaders. It is possible that this development will eventually lead to the creation of an army loyal first to the government of China rather than the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.

CHANGES IN FORCE STRUCTURE AND DOCTRINE

In the first few years of the 1980s, the PLA underwent another reduction in its forces. Faced with limited funding from the central government, a cut in the PLA's size permitted the money that was available to be spread among fewer units. More important, this streamlining also removed organizations with largely nonmilitary missions from the force structure. The Railroad Construction Corps was turned over to the Ministry of Railways, and the Capital Construction Corps (founded in 1966) and Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (created in the early 1950s) were removed from the PLA's control.

Security and border defense units were transferred to the newly created paramilitary People's Armed Police (PAP). The PAP's main mission was (and is) domestic security, which, in theory, allowed the PLA to concentrate more on its external defense role. Still, the PLA retained a secondary mission of internal security, and the PAP forces assigned to each province retained an external defense role to act as local forces during an invasion of the mainland. In 1984, a reserve force was established that began to assume some of the tasks that traditionally were assigned to the militia. Demobilized soldiers would man the new reserve units, which could be maintained for much less cost than active-duty forces.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, PLA strategists began considering a doctrinal modification that envisioned defending China closer to its borders and fighting the Soviets in a more mobile style of war with a combined arms and joint force. Nuclear weapons were considered likely to be used. This new doctrine was named “People's War under Modern Conditions,” and called for a more flexible PLA that incorporated increased numbers of modern weapons into its inventory. Ironically, the PLA was adopting many of the concepts advocated by Luo Ruiqing fifteen years earlier.

Emphasis in the ground forces shifted from light infantry to mechanized, combined arms operations with tanks, self-propelled artillery, and armored personnel carriers. This type of equipment added more mobility to portions of the force and, if properly outfitted, could provide a degree of protection from the nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons the Soviets were expected to employ. However, because of the size and backwardness of the force, the cost of equipping enough of it with sufficient modern weapons to fight the Soviets was prohibitive.

The Chinese defense industries were not up to the task of producing state-of-the-art weapons, so the PLA basically had to make do with the weapons in its inventory, upgraded with a few modifications. Because of its improved relations with many Western countries, for the first time China had the opportunity to shop for weapons from foreign suppliers, including the United States, France, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Israel. The Chinese defense industries used this access to foreign technology to improve their capabilities by obtaining licenses for production or reverse engineering some of these systems. However, only a few small purchases of more modern equipment and subsystems could be afforded, and these went only to selected units and were used primarily for experimental purposes. Out of necessity, a large portion of the PLA remained best structured for the old-style People's War.

Nevertheless, improvements in general force readiness were made. Something as simple as equipping PLA infantry units with enough trucks to make them road mobile was a relatively inexpensive improvement that greatly increased the speed and distance forces could maneuver. Military training received renewed emphasis. In 1981, the PLA held a large multiservice training exercise near Zhangjiakou northwest of Beijing that began the process of incorporating more complex tasks into Chinese military operations. The Zhangjiakou exercise featured extensive PLA Air Force involvement, including the use of airborne troops. (China's first parachute unit was formed in 1950 and subordinated to the PLA Air Force. In 1961, that division-size unit was incorporated into the Fifteenth Airborne Army, which had been formed out of the army's Fifteenth Army that had fought in Korea.) Officer training was enhanced and many older cadres were forced to retire. Age limits were established for the various levels of command, allowing younger officers with a more modern approach to war the opportunity to advance.

In a major strategic reassessment, Deng declared in 1985 that the threat of a major war was remote. Instead, Deng forecast the more likely scenario would be limited, “Local War” fought on China's periphery. A reduction of another million personnel was also announced. Military planners began to think about how such a Local War would be fought and how the PLA should be structured to meet its new challenges. While the doctrine to fight Local War was being developed, People's War under Modern Conditions remained the PLA's primary doctrine for planning and training purposes. Because both doctrines were modernizations over the People's War concept, many of the changes applicable to People's War under Modern Conditions also were appropriate for Local War. At the same time, a small number of theoreticians in a few academic institutions began playing with concepts that later would become known as “Information Warfare,” but these ideas did not receive much attention with all the other changes underway in the PLA.

By 1988 the personnel reduction was complete, and the force numbered slightly over three million. Perhaps the changes that most symbolized the professionalization of the PLA were the reintroduction of ranks and the issuing of new uniforms. (The soft caps with their big red stars and the “Mao” jackets were replaced by larger “saucer” caps with hard bills and Western-style jackets with insignia of rank on the shoulders; neckties were introduced for both men and women.) Among other changes, the eleven military regions were reduced to seven, the thirty-five infantry corps were reduced to twenty-four group armies (corps-size combined arms units), and hundreds of units at the regimental level and above were disbanded.

A major organizational development peculiar to the doctrine of Local War was the formation of small, mobile “Fist” or “Rapid Reaction Units” (RRU). RRUs were found in all military regions and could be deployed locally or wherever needed in the country. Among the group armies and within the PLA Air Force and Navy, a few units were at least partially equipped with new weapons and placed on call to be deployed within hours of alert. RRUs received priority in training and would take part in the experiments that tested tactical concepts necessary for implementing the Local War doctrine. The air force's airborne army of three divisions was designated the primary strategic RRU. The navy's 5,000-man marine brigade, formed in 1980, could also perform rapid reaction missions.

In 1986, an Army Aviation Corps, composed mainly of helicopters, was established. This organization would be the backbone for the new helicopter units that would be added over the next decade. Still, in absolute terms, the number of helicopters available to the ground forces was extremely limited. With only a few helicopter units spread out all over the country, the percentage of infantry units that could be trained to proficiency in air mobile operations was very small.

A NEW PLA LEADERSHIP AND NEW PROBLEMS FOR THE 1990s

By the late 1980s, China's military leadership had undergone further changes. In 1988, Yang Shangkun became president of the PRC and retained his position as vice chairman of the CMC; Qin Jiwei was named minister of national defense. A year earlier, Chi Haotian had succeeded Yang Dezhi as chief of the general staff and Yang Baibing, the half-brother of Yang Shangkun, was appointed director of the General Political Department and later became a member of the CMC.

Defense budgets remained tight through the end of the 1980s. Even as the civilian economy expanded, the PLA was encouraged to support itself through commercial activities in addition to its traditional sideline agricultural and light industrial production. The Chinese defense industries sought foreign markets for their weapons and to develop new systems for export. The PLA created import-export companies to sell excess weapons from its own inventory. At first, most of the actual commercial activity was conducted by elements at higher headquarters, but gradually combat units also got into the act of running hotels and restaurants and performing other services. Transportation and construction engineer units hired themselves out to work on projects with no direct military application. Within a few years, up to 20,000 PLA enterprises were in operation, but the actual number of companies and how much they were earning, or losing, was not known. In the rush to reap profits, economic competition developed among PLA units and local governments and businesses. Some units became involved in smuggling operations. Graft and corruption spread. Profits were problematic. The PLA's participation in this sector of Chinese society was not turning out as expected.

Following the death of Hu Yaobang in April 1989, the PLA's loyalty to the party was put to its greatest test. Over a six-week period, as demonstrators calling for democracy, government reform, and an end to corruption grew in numbers in Beijing, normal daily life around Tiananmen Square and throughout much of the city (and country) was increasingly disrupted. Party and government leaders were particularly embarrassed during the long-scheduled summit with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in May. Beijing was placed under martial law and PLA units from all over the country were ordered to the city to assist in maintaining order. Efforts to talk with the demonstrators or intimidate them with the use of nonlethal force failed.

Though some military leaders, both active and retired, opposed the use of force against the peaceful demonstrators, Deng Xiaoping exerted his personal influence with the military high command. When the domestic police and PAP forces were unable to disperse the crowds from Tiananmen, the PLA was called in. In the chaos that followed, hundreds and possibly thousands of civilians (as well as some soldiers) were killed as tanks, armored vehicles, and truckloads of soldiers moved to retake the center of the city. The PLA obediently but reluctantly followed the orders of its civilian leadership and restored order. In doing so, it tarnished the reputation it had rebuilt with the Chinese people in the years since the Cultural Revolution.

A few weeks after the bloodshed, many of the soldiers who were involved in the military action in Beijing received silver wristwatches for their participation. At the top of the watch's pale yellow face was a red outline of the Tiananmen rostrum; on the bottom, a profile of a PLA soldier wearing a green helmet. Under the soldier were the figures “89.6” (for June 1989) and the characters “In Commemoration of Quelling the Rebellion.” Inscribed on the back were the characters “Presented by the Beijing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and the People's Government of Beijing.” In the following years, these watches were often found in flea markets in Beijing, broken, their hands no longer working, discarded by the soldiers to whom they had been presented.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

This chapter relies heavily on the two-decades worth of books and articles by three scholars who lead the field in the study of Chinese military professionalism. For further information about the development of the PLA's military doctrine and strategy, force structure, and “red” versus “expert” debate, see Harlan Jencks, From Muskets to Missiles: Politics and Professionalism in the Chinese Army; 1945–1981 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1982); Paul H. B. Godwin, The Chinese Communist Armed Forces (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press, 1988); Ellis Joffe, The Chinese Army after Mao (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987); or any of their other shorter works.

Michael Swaine, The Military & Political Succession in China (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1992) updated William Whitson's classic The Chinese High Command and outlines the PLA's personal relationship networks into the early 1990s. Monte Bullard, China's Political-Military Evolution: The Party and the Military in the PRC, 1960–1984 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1985) covers the entry and exit of the PLA in domestic politics, as well as its efforts toward professionalization in the early 1980s.

Kenneth W. Allen, Jonathan Pollack, and Glenn Krumel, China's Air Force Enters the 21st Century (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1995) provides a level of detail about the PLA Air Force's history and current status unmatched in any other work.

John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988) and John Wilson Lewis and Hua Di, “China's Ballistic Missile Programs: Technologies, Strategies, Goals,” International Security 17 (1992): 5–40 describe the strategic setting and research and development efforts that resulted in the creation of China's nuclear arsenal.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

When the political situation in China permits it and the PLA opens its records for research, a military analysis of the events of April through June 1989 would be illuminating. Timothy Brook, Quelling the People (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992) has already attempted a military analysis based on non-Chinese sources for this sensitive time in PLA history.