FIFTEEN

China's Foreign Conflicts since 1949

China's leaders have tended to use force as an instrument of foreign policy when they believed it was important to take a strong stand on matters affecting sovereignty, including reinforcing territorial claims; to maintain safe buffer zones, free from what Beijing perceived as foreign intervention; and to back up strong diplomatic threats with the coercive power to make other countries take China seriously. This approach is deeply rooted in Chinese history, where strong states established relations of suzerainty over weaker ones, regarding them as “vassal states” (shuguo) and punishing them with military expeditions when they failed to do the bidding of the stronger kingdom.

From the time of the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 to 1988, Beijing used force to resolve international disputes in numerous cases: the Korean War in 1950, two artillery bombardments and crises over Taiwan's offshore islands in 1954 and 1958, incursions into Burma in 1960 and 1961, road construction in Laos and the provisions of air defense protection there in the 1960s, the war with India in 1962, a mobilization on the Indian border in 1965 to relieve pressure on Pakistan by Indian forces, border skirmishes with the Soviet Union in 1969, large military deployments to Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s, the seizure of the Paracel Islands in 1974, a standoff with Japan over the Senkaku Islands in 1978, the Chinese attack into Vietnam in 1979, and the seizure of islands in the Spratly Archipelago in 1988.1 China has also exercised its military might by firing missiles off Taiwan in 1995 and 1996; by seizing Mischief Reef, claimed by the Philippines, in 1995; and by threatening to employ nuclear weapons against the United States in the event it came to the aid of Taiwan should Beijing use force to reunite the island with the mainland.

On April 1, 2001, in response to a U.S. Navy aerial reconnaissance mission over international waters, a People's Liberation Army (PLA) Naval Air Force fighter aircraft attempted to intercept the U.S. EP-3 aircraft. The two collided seventy miles off Hainan Island, seriously damaging the American plane. The Chinese fighter crashed, killing the pilot. China's aircraft and vessels also harassed two unarmed American ocean surveillance vessels operating in international waters off China in 2009. In addition, the PRC deployed a naval task force to the Gulf of Aden in 2008 to operate independently of but alongside a multinational counterpiracy effort in the region.

In every instance of China's use of force, its leaders have claimed that their actions were based solely on self-defense. And because of its expansive territorial claims, China's diplomatic and military establishments maintain that only in rare cases do China's forces enter foreign territory: Korea in 1950 and Vietnam in 1979. In some cases, of course, Beijing doesn't acknowledge that its forces were deployed in combat, such as in Vietnam and Laos during the war with the United States in the 1960s and 1970s.

It is useful to clarify what the use of force means in general military terminology, for what is true in general is also applicable to China. A simplistic understanding of the term would be the conduct of overt military action by the PLA in an actual attack on another country or sovereign state. But the use of force can be subtler than that, and it may not amount to actual combat. Military demonstrations are also a use of force, as are well-timed military exercises, weapons tests, and troop, naval, or air deployments. In November 2000, for instance, Beijing tested its newest-generation roadmobile missile, the DF-31, while the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the United States, General Hugh Shelton, was visiting China. This not-sosubtle demonstration of force was meant to underscore just how seriously Beijing takes American military sales to Taiwan. China's aggressive intercepts of American reconnaissance flights—such as the aforementioned collision in April 2001—represent demonstrations of force. In late May and early June 2001, the PLA conducted an extensive series of amphibious exercises in the area of Dongshan Island in south China, exercises timed to show Beijing's displeasure over Taiwan president Chen Shui-bian's visit to New York on May 21–23 and his meetings with American citizens. Thus, a military training evolution involving an overflight of the Spratly Islands by Chinese bombers is just as much a use of military force as the seizure of the Paracel Islands from the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) in 1974. Indeed, some uses of force are mutually reinforcing. For instance, China's entry into the Korean War in 1950 and its willingness to fight India in 1962 made its warnings to the United States about the scope of combat in the Vietnam War all the more credible.2

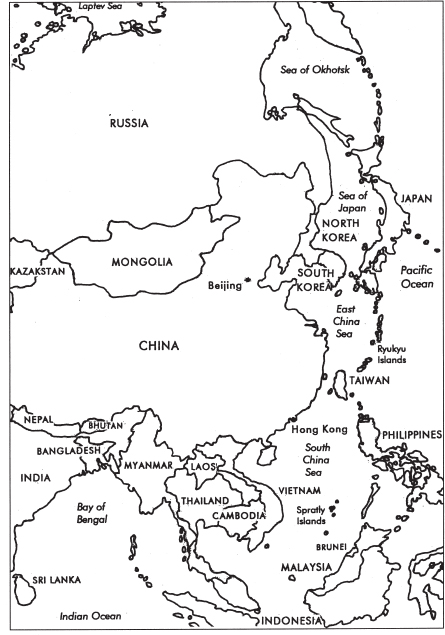

Map 15.1 China and its neighbors at the end of the twentieth century. Adapted by Don Graff based upon “Eurasia,” in Fire in the East, Paul Bracken (New York: HarperCollins, 1999).

Two researchers from the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, California, Michael D. Swaine and Ashley J. Tellis, have identified “five core features” of Chinese security behavior over the past one thousand years in which the use of force is significant. In their book Interpreting China's Grand Strategy: Past, Present, and Future, Swaine and Tellis argue that the broad historical pattern of the use of force by China has five key features: (1) an effort to protect a central heartland while maintaining control over China's “strategic periphery”; (2) expansion or contraction of peripheral control, depending on the strength of the regime and its capacity; (3) “the frequent yet limited use of force against external entities, primarily for heartland defense and peripheral control, and often on the basis of pragmatic calculations of relative power and effect”; (4) a reliance on less than coercive strategies when the state is weak; and (5) a strong relationship between the power and influence of domestic leadership and the use of force.3 Imperial China, like the PRC, used force frequently. In the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), China engaged in an average of one external conflict a year.4

It is important for students of history to note not only when Chinese leaders tend to resort to force in international affairs but also how they exert it. In times of crisis or threat, Chinese leaders use force to create a political shock that reinforces an important principle, such as sovereignty. Despite Beijing's claims that its actions are defensive, China often uses force in a preemptive manner—for instance, if leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) perceive that a foreign country is ignoring clear signals that a certain action will trigger a reaction by the PLA. Part of Beijing's justification for resorting to force is often based on the perception, perpetuated by the CCP, that the period between 1840 and 1949 consisted of a “century of national humiliation” by foreign imperial powers. The interval between the Opium War and the establishment of the People's Republic of China is treated in the history books as a period when foreign countries used force of arms to impose their will on China, including the acquisition of extraterritorial privileges and the creation of foreign concession areas.

John Garver has set out a typology of when Chinese leaders decide to use force, based on the underlying goals of the action: “(1) deterring superpower attack against China; (2) defending Chinese territory against encroachment; (3) bringing ‘lost’ Chinese territory under Chinese control; (4) enhancing regional influence; and (5) enhancing China's global stature.”5 These goals are not mutually exclusive, but they may well be complementary. For instance, when China entered the Korean War in 1950, Mao Zedong and the CCP leadership believed that they were not only defending Chinese territory against encroachment but also strengthening China's regional influence and global stature. The DF–31 missile test cited earlier was also designed to deter a superpower from intervening and attacking Chinese forces engaged in any future attempt to bring the “lost” territory of Taiwan back under Beijing's control. With this typology in mind, this chapter examines a few of the major cases in which China resorted to force in external affairs and discusses which of the five underlying goals of action seem to be in play. Tibet and Xinjiang are not discussed here because these areas were ruled from China during the Yuan (1279–1368) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties, and there is no challenge to China's sovereignty there by either the United States or the United Nations. The case of the offshore islands held by the Republic of China on Taiwan is included because the 1958 Taiwan Strait Crisis involved the United States.

THE KOREAN WAR

The Korean War began on June 25, 1950, when Communist North Korea (the Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) invaded South Korea (the Republic of Korea; ROK). On the same day, the U.N. Security Council condemned the aggression. The North Korean People's Army (NKPA) rapidly overcame the ROK forces. Seoul fell to the NKPA on June 27, 1950, and the South Korean army was defeated. That day, the United Nations asked its members to assist South Korea.

Responding to the crisis, President Truman ordered U.S. ground forces into Korea on June 30, 1950. The newly formed unit sent into action, Task Force Smith, had been created from U.S. occupation forces in Japan. It confronted NKPA forces in the vicinity of Osan on July 5, 1950. The U.S. force was easily overrun. Its troops were not trained to fight as an organized team, they were not in shape for combat, and their outdated weapons were no match for the NKPA's Soviet-made tanks and artillery. U.S. forces fell back and established the Pusan Perimeter on August 4. The U.S. commander, Lieutenant General Walton H. (Johnny) Walker, and his Eighth Army held the perimeter stubbornly against determined attacks from NKPA forces through August and into September 1950.

At the outbreak of the Korean War, China and the United States had no diplomatic relations because the United States still recognized the Republic of China as the legitimate government of China. Thus, American and Communist Chinese diplomats had no direct means by which they could engage in a dialogue. On September 1, 1950, referring to North Korea, PRC leader Mao Zedong publicly stated in the press that China could not tolerate the invasion of a neighbor, a signal intended to deter U.S. and U.N. forces from going into the DPRK. Two days later, Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai formally warned the United States and the United Nations, through the Indian ambassador Sardar K. M. Panikkar, that the Chinese would intervene if U.S. forces entered North Korea. These warnings were dismissed by the United States as unreliable or mere bluff.

The momentum of the war dramatically shifted against the NKPA after the successful amphibious landing of U.S. forces at Inchon, south of Seoul, on September 15, 1950. On September 18, U.N. forces broke out from the Pusan Perimeter and attacked north and west. The NKPA, caught between General Douglas Mac Arthur's “anvil” at Inchon and Walker's Eighth Army “hammer” in pursuit, rapidly collapsed. Seoul was liberated on September 26.

Four days later, Zhou Enlai publicly reiterated the warning that China would not tolerate the invasion of one of its neighbors. This was an important way of declaring that China viewed such an attack as an encroachment on its sphere of influence that undermined its stature in the region and the world. Continuing to discount these warnings, however, U.N. forces pushed north. On October 1, ROK forces crossed the 38th parallel, and MacArthur called for the surrender of the North Korean capital, Pyongyang. On October 7, U.N. forces crossed the 38th parallel. Pyongyang was captured on October 19.

China began to react to the U.S. move into the north. The first campaign of the Chinese People's Volunteers (CPV) was launched in secret, surprising American and ROK forces. Chinese forces, consisting primarily of light infantry, had begun crossing the Yalu River border between China and North Korea on October 18–19, under the command of Peng Dehuai. The CPV moved at night and hid during the day to conceal its intentions.

On November 1, the CPV ambushed the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division at Unsan on the western side of the peninsula. Although intelligence reports had indicated the presence of Chinese forces, they were believed to be no more than about 70,000 strong. In reality, more than 200,000 Chinese soldiers were already in Korea. The U.S. X Corps, which had landed on the east coast of North Korea at Wonsan on October 26, moved toward the Yalu River between November 10 and 26, while the U.S. Eighth Army advanced in the west. General MacArthur launched his final “Home by Christmas” offensive on November 24, 1950.

The second CPV campaign, from November 25 to December 24, 1950, succeeded not only in stopping the advance to the Yalu River but also in driving the U.N. forces completely out of North Korea. On November 25, the CPV attacked the Eighth Army at Ch'ongch'on River in the west. Two days later, CPV forces in the east assaulted the U.S. 1st Marine Division and the U.S. Army's 7th Infantry Division at Chosin Reservoir. Between November 26 and December 1, the U.S. 2nd and 25th Infantry Divisions were defeated along the Ch'ongch'on River and forced to retreat. In the east, between November 27 and December 10, the X Corps fought through CPV forces to the port of Hungnam, while the 1st Marine Division was forced to retreat from Kot'o-ri. By December 24, when the X Corps sailed from Hungnam, U.N. forces had been completely expelled from North Korea.

The third CPV campaign was launched on December 31, 1950, against Peng Dehuai's advice. Peng attempted to convince Mao that the U.N. forces had consolidated into an in-depth defensive position and that the CPV forces lacked experience fighting against fortified positions. The CPV logistics lines were also overextended, Peng argued, and Chinese troops lacked sufficient food, winter clothing, and other essential supplies. Further, after pushing from northeast China through the length of North Korea, CPV soldiers were exhausted and in need of rest and reorganization. A desire to end the war quickly, combined with the sweeping victories over the U.N. forces, however, encouraged Mao to order the CPV to push southward despite Peng's concerns. On January 4, 1951, Seoul fell, and by January 14, the U.N. line was pushed back to the 37th parallel.

On January 25, 1951, U.N. and U.S. forces resumed the offensive. Within two days, the CPV began its fourth campaign, which lasted until April 21. On February 14, the U.S. 23rd Infantry Regiment, with help from the French Infantry Battalion, turned back a CPV counteroffensive at Chipyong-ni. The United Nations seized the initiative between February 17 and March 17, 1951, and moved north. Seoul was liberated for a second time on March 18. During this fighting, on April 11, General MacArthur was relieved and General Matthew B. Ridgeway assumed command of U.N. and U.S. forces.

The fifth CPV campaign was launched between April 22 and May 21, 1951. On April 22, the CPV attacked the British Brigade northwest of Seoul near the Imjin River with a force of 50,000 men. U.N. lines held, and the CPV broke contact on April 30. U.S. forces halted the CPV Soyan Offensive between May 16 and 22, 1951. U.N. forces began to push north on May 23 and reached the 38th parallel on June 13. The Soviet delegate at the United Nations, Jacob Malik, proposed a truce on June 23. Talks began at Kaesong on July 10, but an armistice was not signed until July 23, 1953. The bloodiest fighting of the war (and an intensive Communist propaganda campaign) occurred during the intervening two years.

From August 1 to October 23, 1951, in an effort to straighten its lines, the United Nations launched a series of limited battles known as Bloody Ridge and Heartbreak Ridge. In late October, peace talks resumed at Panmunjom, and a cease-fire was agreed to at the line of contact. Between November 1951 and April 1952, there was a stalemate along the battlefront while the Panmunjom talks continued.

On January 28, 1952, the CPV headquarters reported that U.S. and U.N. planes had spread smallpox in areas southeast of Inchon. On February 18, Radio Moscow accused the United States of using bacteriological warfare against North Korea. By March, a campaign against germ warfare had been launched in China. Although the Chinese have never retracted their charge that the Americans used germ warfare in Korea, their claim has never been supported by scientific evidence.

Between June and October 1952, truce talks were deadlocked over how to handle the repatriation of prisoners of war (POWs). A number of hill battles were fought, including Baldy and Whitehorse. On October 8, 1952, truce talks recessed and fighting resumed. The ROK army was faced with particularly heavy fighting in the Kumwha sector until November 1952, during which the South Koreans distinguished themselves as tough and courageous soldiers.

India offered a plan to resolve the POW issue to the United Nations in November 1952, and on March 30, 1953, Zhou Enlai indicated the Chinese—would accept the Indian proposal. The talks at Panmunjom resumed. As the negotiations continued, one of the bloodiest combats of the war, the Battle of Pork Chop Hill, occurred on April 16–18, 1953. From April 20 through 26, both sides exchanged sick and wounded POWs at Panmunjom.

On June 4, 1953, the Chinese and North Koreans agreed to accept U.N. truce proposals, and the fighting ceased. On September 4, screening and repatriation of POWs began at Freedom Village, Panmunjom. CPV forces remained in North Korea until 1958.

The Korean War stands out as China's only sustained foreign conflict in the second half of the twentieth century. The war took place at a time when the new Communist regime had the determination, confidence, and trained manpower to confront the might of the United States and its allies in battle. The indecisive outcome was considered a moral victory by the Chinese and made the point that the PRC was not to be trifled with.

TAIWAN STRAIT CRISIS OF 1958

Sino-U.S. talks in Geneva over bilateral recognition and the return of U.S. prisoners from the Korean War broke down by 1957. When the U.S. ambassador in Geneva, U. Alexis Johnson, left for another diplomatic assignment in December 1957, no replacement was assigned. By June 1958, after requesting the continuation of talks and the assignment of a new U.S. ambassador, Beijing decided to use military force to demonstrate to the Americans why they had no choice but to deal with China. The CCP Central Military Commission met over a period of two months, during May-July 1958, to determine how to bring military force to bear on the situation.

Beijing first initiated a strong propaganda campaign in its internal and external media calling for the “liberation of Taiwan.” This lasted through June and July. During a July 1958 visit to Beijing by Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, Mao Zedong reportedly failed to apprise him of plans for Chinese military action. Following Khrushchev's visit, the PLA Air Force began to deploy to forward airfields. On August 23, the PLA started shelling the Nationalist-held offshore island of Quemoy (Jinmen), firing more than 30,000 rounds on the first day of the campaign. The United States, meanwhile, rushed six aircraft carrier battle groups to the area and sent in combat aircraft and transports. U.S. ships even escorted Nationalist vessels up to the three-mile territorial limit while they resupplied the offshore islands. Other U.S. support arrived, including atomic-capable 8-inch howitzers (which were deployed on the offshore islands) and air-to-air missiles. Taiwan and the mainland fought seven air battles between August 23 and the end of October. China, meanwhile, began to receive surface-to-air missiles (the SA-2) from Moscow. In the end, no invasion of Quemoy or Matsu, the other major Nationalist-held offshore island, was mounted. China and the Soviet Union split over assessments of whether the United States was willing to risk war with the socialist camp, and U.S. support continued to flow into Taiwan.

THE SINO-INDIAN WAR

After driving Indian forces out of the area around the hamlet of Longju in August 1959, China continued to observe the McMahon Line, drawn in 1914, as the de facto border between Tibet and India's northeastern region of Assam.6 Chinese forces pulled back from disputed territory that same month to avoid further incidents. In the western sector of the border, where China and India had clashed in October 1959, Indian forces, under New Delhi's orders, began a “forward policy” designed to push the disputed boundaries out to geographic features favorable to, and claimed by, India.

In the east, on the McMahon Line, Indian forces had avoided patrolling within two miles of the border after 1959. But in December 1961 they were ordered to move forward and begin patrolling again along the disputed line. During the first six months of 1962, the Indian army was to establish twenty-four new border outposts. In June 1962, a platoon of the Indian Assam Rifles moved about four miles north of the McMahon Line to the Thagla Ridge, which they treated as the border. Indian troops established a position there on June 4, even though India's own maps showed the ridge to be in Chinese territory. On September 8, a Chinese force advanced on the Thagla post, attempting to press the Indians to withdraw. Beijing also issued a diplomatic protest on September 16, complaining about the presence of the Indian troops.

The Indian government took the position that when Sir Henry McMahon drew the line in 1914, he had intended that it run along the line of the highest ridges. They argued that the Thagla Ridge was the dominant terrain feature and should therefore be the border. The Chinese reaction, according to India, was to implement a central policy to advance the border into Indian territory. India began a buildup of forces that was logistically insupportable and militarily dangerous, while Chinese forces increased their strength and weaponry along the border using a road system that would support five- and even seven-ton vehicles. Through September, there were skirmishes around the Thagla area, and both sides took casualties. By October, despite bad weather and unfavorable terrain, the Indians made a move.

On October 10, 1962, the Indian army was ordered to carry out Operation Leghorn, designed to push the Chinese back. But Chinese intelligence was aware of the operation, and Beijing issued a warning to India in the form of a diplomatic note on October 6. Meanwhile, the PLA concentrated superior forces and artillery in the area. On the night of October 19, Chinese troops assembled in assault positions, and on the morning of October 29, they attacked the Thagla Ridge, wiping out the Indian 7th Brigade and capturing its commander.

In the western sector of the border, along the Galwan River, the PLA launched a simultaneous attack against Indian forces in the Chip Chap River valley. The Chinese government declared these to be self-defensive counterattacks to clear Indian troops out of Chinese territory. American supplies, meanwhile, began to flow into India, with about twenty tons of military equipment arriving each day. Great Britain also provided assistance.

An Indian counterattack along the McMahon Line was beaten back by Chinese forces in November, while Indian troops in the west were also trounced by the Chinese. By November 21, China had announced a unilateral cease-fire. The Chinese simultaneously announced a December 1, 1962, withdrawal to positions twenty kilometers behind the “line of actual control” that had existed between China and India on November 7, 1959, reviving a formula used to defuse a crisis that year. Indian figures indicate that 1,383 troops were killed, 1,696 were missing in the operation, and 3,968 were captured by Chinese forces. The Chinese, having incurred far fewer losses, were left in control of the Aksai Chin plateau.

THE ZHENBAO ISLAND CLASH

After about a year of confrontation between the PLA and the Soviet army over demarcation on the eastern border, on March 2, 1969, a major clash broke out at Zhenbao Island (called Damansky by the Russians), located on the Ussuri River between the cities of Khabarovsk and Vladivostok. The Chinese maintained that the border between the two countries followed the Thalweg principle, or the central line of the main channel, putting the island on the Chinese side. Moscow claimed that the Chinese banks of the Amur and Ussuri Rivers were the border, putting some 600 disputed islands on the Russian side.

As each side patrolled, physical clashes became more common. Then, on March 2, a Chinese patrol crossing the frozen river to the island was challenged by Russian forces. Automatic weapons fire from the Chinese bank hit the Russian forces, killing seven Russians and wounding twentythree. The Chinese, who said the Russians fired on their patrol first, also claimed to have suffered several casualties. It is not clear from accounts by either side, however, whether the PLA instigated the incident or the Soviets initiated fire. On March 4 and 12, the Russians reinforced the island and flew reconnaissance aircraft along the border. Then, on March 15, 200 Russian infantrymen supported by thirty armored vehicles again tried to seize the island. Clashes continued through March 17, when both sides de-escalated the conflict. Tensions continued, however, for several years.

PARACEL ISLANDS

A neomaritime spirit arose in China in 1973 with the reappearance of Deng Xiaoping as vice chairman of the CCP Central Military Commission. Soon after that, the PRC initiated its campaign to seize the Paracel (Xisha) Islands from South Vietnam. Deng had close contacts with the head of the navy, Su Zhenhua, and was a leading supporter of a more maritimeoriented approach for the PLA Navy, which had been principally a coastal, or “brown water,” force. Thus, Deng was apparently closely linked with events in the Paracel Islands, just as he would be with the 1979 attack into Vietnam described later. The seizure of the Paracels, therefore, must be viewed as a means of developing a more active maritime role for China, as well as a statement of sovereignty and control over claimed territory in the South China Sea.

On January 11, 1974, China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a public warning that the PRC had indisputable sovereignty over the Paracels, adding that the “sea areas around them also belong to China.” Four days later, the PLA Navy began moving forces into position. According to South Vietnamese survivors, China first began to move fishing vessels into the area, a tactic that seems to be common whenever China is seeking to reinforce its maritime claims. The fishermen serve not only as a visible representation of China's rights to the area but also as advance reconnaissance for the Chinese navy.

On January 15, South Vietnamese ships allegedly attempted to displace the fishermen and two Chinese patrol boats in their vicinity from the waters surrounding the islands. By that time, the PLA had assembled a naval force consisting of about eleven warships, some of which carried more than 600 assault troops. Fighter aircraft based on Hainan Island, about 130 miles northeast of the Paracels, were available for air cover. On January 17, several Chinese patrol vessels arrived, followed by ten other warships. The South Vietnamese had a former U.S. Coast Guard cutter with a 5-inch gun and four destroyer escorts, each armed with two 3-inch guns. They had no air support. In the ensuing naval engagement, a missile from a Chinese patrol craft reportedly hit one of South Vietnam's destroyer escorts. Within two days, Vietnam's naval forces were overwhelmed and forced to withdraw. The 600 PLA assault troops, trained for amphibious operations, had landed and taken control of the Paracels. Chinese press releases on the incident emphasized the participation of “people's-militia fishermen” in the seizure of the islands, a common theme in Chinese military actions involving what Beijing considers to be its sovereign territory. The Chinese claimed that South Vietnamese forces suffered 300 casualties in the engagement and that the PRC captured 49 Vietnamese military personnel who were later returned to Vietnam.

This action marked the first time China used military force after the improvement in U.S.-China relations in January 1972. Washington took no action, and Hanoi was not in a position to react either. The Paracel Islands operation of 1974 is notable because it marked the only Chinese amphibious operation involving the projection of troops across any distance, even if it involved only eleven ships and some 600 ground troops.

THE “SELF-DEFENSIVE COUNTERATTACK” AGAINST VIETNAM

Between 1978 and early 1979, Vietnamese military forces began operations in Cambodia designed to drive Pol Pot and his Maoist-oriented regime from power. By January 1979, Vietnamese forces had seized Phnom Penh and were soon poised on the Cambodian-Thai border, where they threatened Thailand. Beijing, a major supporter of Pol Pot, also had good relations with the Thai government. In response to Vietnam's military moves, the Chinese government complained about a series of violations along the Sino-Vietnamese border, threatening punitive action over alleged incursions into China. During January and into mid-February, the PLA moved main field-force armies and divisions from around China to staging areas north of the Vietnamese border. Between thirty and forty divisions were eventually assembled, often moving by rail under cover of night. At the same time, fearing a Soviet response in the north because of the treaty of friendship and cooperation signed by Moscow and Hanoi in November 1978, China made preparations to defend the north against any potential Soviet counterattack.

Chinese forces aligned on the Vietnamese border in one theater of operations, while another theater of operations was formed in the north. The Northern Theater (Zhanqu) comprised the Shenyang, Beijing, Jinan, Lanzhou, and Xinjiang military regions (MRs). Li Desheng, commander of the Shenyang MR, was appointed theater commander along the Sino-Soviet border. Preparations in the north were mainly defensive, including evacuating civilians along the border and raising the readiness levels of Chinese forces.

The Southern Theater along the Sino-Vietnamese border was divided into two subtheaters, or zones of operation: the Eastern in Guangxi province opposite Lang Son, and the Western in Yunnan province opposite Lao Cai. Xu Shiyou, who as Guangzhou MR commander also controlled the Eastern subtheater, commanded the entire Southern Theater. Yang Dezhi, the Kunming MR commander, was in control of the Western subtheater. In Beijing, Deng Xiaoping controlled forces in both the Northern and Southern Theaters for the Central Military Commission, with marshals Xu Xiangqian and Nie Rongzhen as deputies. Geng Biao, chief of the general staff of the PLA, was responsible for coordinating the operation.

On February 17, 1979, Chinese forces attacked across the Vietnamese border, advancing along five main axes: in the Eastern subtheater against Lang Son and Cao Bang, and in the west against Ha Giang, Lao Cai, and Lai Chao. Logistics and service support for Chinese forces came from local-force and militia units in the two military regions.

The Vietnamese had responded to the pre-attack Chinese buildup by moving forces north from around Hanoi and by withdrawing some mainforce units from Cambodia. Vietnam also relied heavily on local-force and militia units. China had announced its attention only to “punish Vietnam” for border incursions, saying that the attack would be limited to an advance of no more than fifty kilometers into Vietnam. After initial progress against very heavy resistance, the Chinese forces halted, concentrated on consolidating around major cities, and began an orderly withdrawal that was completed by March 17, 1979. In the process of the campaign, the Vietnamese claimed to have killed or wounded 42,000 Chinese, while Beijing said it had inflicted 50,000 casualties on Vietnam with a loss of only 20,000. The Vietnamese estimates are probably closer to the actual outcome.

In the conflict, the PLA units suffered from poor command and control, poor logistics, and an inability to coordinate large formations on the battlefield. After the attack on Vietnam, the PLA began to discuss restructuring its group armies and restoring a rank structure to facilitate battlefield command and control. In combat training, the PLA began to focus on combined arms operations so that its infantry, armor, artillery, and engineers worked in coordination. The PLA also sought to develop rapid reaction forces and to reorganize its military logistics structure.

NANSHA (SPRATLY) ISLANDS INCIDENTS

Since the Nansha, or Spratly, archipelagic chain in the South China Sea may be the site of a major oil source (as confirmed by recent Chinese and international seismic surveys), the question of sovereignty has become a serious concern among claimants to the islands: China, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Taiwan also occupies one of the islands, Itu Aba.

A January 30, 1980, white paper published by the PRC claimed “indisputable sovereignty over the Xisha (Paracel) and Nansha (Spratly) Islands.” Since both Beijing and Taipei regard Taiwan as a province of China, the Taiwan garrison on Itu Aba reinforces the Chinese claim to sovereignty. China's claims to the islands are based on historical usage by Chinese fishermen as early as 200 B.C.E. and on the 1887 ChineseVietnamese Boundary Convention. Vietnam claims historical links with the islands primarily on the basis of having inherited modern French territory. The Nationalist Chinese abandoned the Spratly Islands in 1950. At the time of South Vietnam's fall in 1975, the Saigon regime occupied four islands. The successor Hanoi government built up the total number of occupied islands to about twenty.

Vietnam remains China's principal antagonist, as exemplified by the March 1988 incident in which the PLA Navy sank three Vietnamese supply vessels. For the PLA Navy, the key to control of the Spratly Islands is not so much developing a growing “blue water” naval capability but rather establishing control over the associated airspace. This problem will not be solved until the PLA Navy either deploys an aircraft carrier or develops an operational air-to-air refueling capability for its naval air arm, thereby ensuring dominance over Vietnam and all other claimants to the Nanshas.

With the perceptions of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member countries in mind, China continued to proceed slowly in exercising its claims over the Nanshas. In a statement issued in Manila in 1994, the Chinese embassy stressed Beijing's “indisputable sovereignty” over the Nansha Islands and adjacent waters. China contracted a U.S. oil company to drill exploratory wells near the Nanshas and said it would defend its claimed sites if necessary. In February 1995, China continued to expand its presence in the Nanshas and took over Mischief Reef, a fifteen-square-mile set of shoals 150 miles west of the Philippine island of Palawan. China acknowledged building several structures on the barely submerged coral reef, ostensibly as “shelters for Chinese fishermen.” China also deployed several ships, believed to be naval vessels, to the area. Philippine president Ramos said the Chinese actions were “inconsistent with international law” and with the 1992 declaration on the Nanshas that was endorsed by China and other claimants to the islands. As recently as the July 1995 ASEAN Regional Forum conference in Brunei, China agreed to abide by the Law of the Sea in negotiating claims to the islands. In spite of that agreement, Beijing has continued to pressure the ASEAN states by sending naval units or fishing fleets into contested areas from time to time.

HISTORIC PLA MISSIONS IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

Hu Jintao, China's president, Communist Party chairman, and head of the Central Military Commission, set out what he characterized as a new set of missions for the PLA, appropriate for the new century, to deal with China's security problems. In a speech to the PLA entitled “Historic Missions of Our Military in the New Century,” given on December 24, 2004, Hu laid out four major tasks for the PLA:

1. To provide an important force for guaranteeing the Party's ruling position;

2. To provide a strong security guarantee for safeguarding the important strategic opportunity period for national development;

3. To provide a powerful strategic support for safeguarding national interests;

4. To play a role in upholding world peace and promoting mutual development.

The first two tasks are traditional responsibilities of China's military. In his speech, Hu Jintao expressed several specific concerns, including ensuring the security of land and maritime borders; separatist tendencies in Taiwan, Xinjiang, and Tibet; terrorism; and China's domestic stability.

Tasks related to safeguarding national interests and promoting world peace have been the impetus behind a more aggressive enforcement of China's maritime claims in the South and East China Seas, leading to incidents with the United States, Japan, Vietnam, and Korea. The deployment of Chinese forces in the Gulf of Aden against Somali pirates represents China's longest continuous naval operation and responds to the last two tasks set out by Hu. These tasks also expand the traditionally insular role of the PLA in and around China and open the door for a military that is capable of enforcing China's national interests on a global scale.

CONCLUSION

In its own National Defense White Paper of October 2000, China claimed to be a country that seeks to resolve disputes in the international arena through negotiations. That claim has been reinforced in subsequent white papers. However, Beijing has clearly stated its right to use force within its own territory, even if that territory is in dispute. The 1988 naval engagements against Vietnam in the Spratly Islands come to mind, as do the 1974 seizure of the Paracel Islands and the 1979 attack on Vietnam. Of course, Beijing has always been careful to couch its actions in terms of a “defensive counterattack” or an attempt to regain territory it claims. More recently, China seized and occupied Mischief Reef, claimed by the Philippines, and demonstrated massive force against Taiwan as a way to express its dissatisfaction with what CCP leaders believed was a trend toward independence. And its interpretation of which military activities are permissible in the Exclusive Economic Zone under the U.N. Treaty on the Law of the Sea has led to clashes with U.S. ships and aircraft operating in international waters off China.

Thus, it is clear that China continues to rely primarily on threats of force and coercion in its relations with neighbors. And China has shown that it will not hesitate to use force to achieve foreign policy goals.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

To understand how China views the use of force and characteristically warns countries before using force, one of the seminal books is Allen S. Whiting, The Chinese Calculus of Deterrence: India and Indochina (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1975). Whiting provides an excellent set of case studies on how China uses strategic warning and diplomacy in combination before using force. For a case study on the same subject, the reader would do well to obtain a copy of Neville Maxwell, India's China War (Bombay: JAICO Press, 1971). Maxwell had access to the Indian classified diplomatic archives, giving his conclusions great credibility.

From the standpoint of strategic culture—when China might resort to force and why—two authors have done an excellent job of putting classical and modern Chinese military thought into perspective. Thomas J. Christensen, Useful Adversaries: Grand Strategy, Domestic Mobilization, and the Sino-American Conflict, 1947–1958 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), uses the early Cold War confrontations between China and the United States to illustrate China's strategic culture. Alastair Iain Johnston, Cultural Realism: Strategic Culture and Grand Strategy in Chinese History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), provides a more historical perspective on the same questions.

Four of the best texts dealing with China's military actions in the Korean War are T. R. Fehrenbach, This Kind of War (New York: Macmillan, 1963); Alexander L. George, The Chinese Communist Army in Action: The Korean War and Its Aftermath (New York: Columbia University Press, 1967); Chen Jian, China's Road to the Korean War: The Making of Sino-American Confrontation (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994); and Shu Guang Zhang, Mao's Military Romanticism: China and the Korean War, 1950–1953 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995). Fehrenbach deals with the conduct of the war from the perspective of the United States, including strategy, foreign policy issues, and military actions. George provides an assessment of how the Chinese military functioned as an instrument of national policy. Chen Jian's and Shu Guang Zhang's books are excellent complements to the other two because they exploit internal Chinese documents that reveal why the PRC entered the war and the role the Soviet Union played in China's decision-making process.

Accurate materials on China's seizure of the Paracel Islands and its actions in the Spratly Islands are not available yet, so one must rely on more general works about China's military activities. Greg Austin's China's Ocean Frontier: International Law, Military Force and National Development (Canberra: Australian National University, 1998) is one book that covers the matter well. Ken Allen, a former U.S. Air Force attaché in China, has studied some instances of the use of force by China; see Kenneth W. Allen, Jonathan Pollack, and Glenn Krumel, China's Air Force Enters the 21st Century (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1995).

The best work on the Chinese attack into Vietnam in 1979 is Edward C. O'Dowd, Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War (New York: Routledge, 2007). O'Dowd makes extensive use of original Vietnamese materials. Harlan Jencks, “China's Punitive War on Vietnam: A Military Assessment,” Asian Survey 19 (1979): 801–815, provides a quick and accurate assessment written only months after the conflict and remains mandatory reading.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

China is increasingly dependent on foreign trade and exports and on imports of energy and food. As China expands its strategic reach through military improvements, it is bound to develop the capability to act when it perceives that its interests are threatened. Moreover, Hu Jintao's 2004 speech seemed to charge the PLA with transforming itself from an insular force focused on China's periphery into a force with global responsibilities congruent with the interests of a major economic power. Still, the military strategic writings from China have made it clear that the PRC does not intend to challenge the United States or other great powers directly in a military sense. There is a need for new research that examines how China can obtain the energy resources it requires and what military and diplomatic measures it will employ to secure them. It is increasingly evident that China's shipping companies are gaining footholds at ports near strategic waterways such as the Panama Canal, the Bosporus, and the Malacca Strait. Will China use arms sales or military deployments to back up its state-owned corporations if its access to resources is threatened? What can one learn from an examination of the history of the Yuan dynasty and the early Ming dynasty (including the voyages of Zheng He), when China pursued maritime expansion that used both force and commerce to advance national interests? Are these actions reflected in modern strategic writings? Will the introduction of effective ballistic missile submarines capable of extended voyages change China's military strategy and how it uses force?

NOTES

1. John W. Garver, Foreign Relations of the People's Republic of China (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1993), 250–265.

2. This point is the thesis of a seminal book on the subject; see Allen S. Whiting, The Chinese Calculus of Deterrence: India and Indochina (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1975).

3. Michael D. Swaine and Ashley J. Tellis, Interpreting China's Grand Strategy: Past, Present, and Future (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2000), 21.

4. Alastair Iain Johnston, Cultural Realism: Strategic Culture and Grand Strategy in Chinese History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), 184.

5. Garver, Foreign Relations of the People's Republic of China, 253–254.

6. Brigadier J. P. Dalvi, Himalayan Blunder: The Curtain-Raiser to the Sino-Indian War of 1962 (Bombay: Thacker, 1969), 43–45.