The Tour’s most memorable places

This stadium-less sport has nevertheless made arenas out of towns, roads and climbs – some the sites of exceptional riding, some places made infamous due to misfortune , some simply areas of natural beauty that, as a backdrop for some exciting racing, never fail to disappoint. All, though, for better or worse, have helped shape Tour de France history – a race that simply is defined by the places it visits.

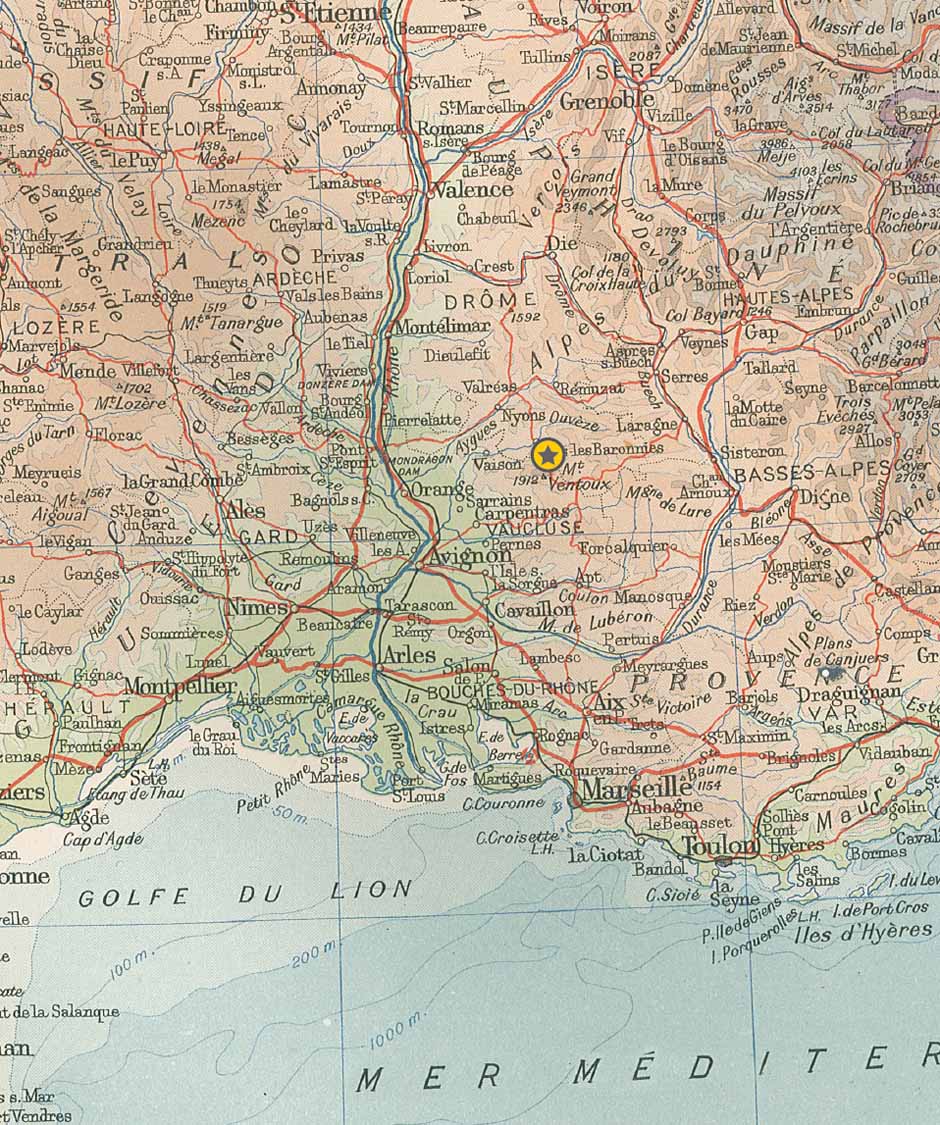

Mont Ventoux, France

‘The police motorbike rider came up to Aimar to tell him that he’d followed him down off the Ventoux – and had clocked him at 140 kph’

The Giant of Provence’ has delivered heartache to so many riders and fans since its first inclusion in the Tour de France in 1951: always tough, always decisive and always, it appears, controversial.

Chiefly, it must take at least partial blame for a rider having died on its flanks: British rider Tom Simpson’s death at the 1967 Tour was attributed to him having ingested amphetamines before the start of that thirteenth stage in Marseille, exacerbated, however, by the extreme heat of the day and the effort of climbing the brutal Ventoux on the exposed southern slopes from the town of Bédoin.

It was also the scene of a ding-dong battle between Marco Pantani and Lance Armstrong at the 2000 Tour. Armstrong, already in yellow, allowed Pantani to win the stage – which offended the Italian climber, in turn angering Armstrong to the extent that the American promised that there would be “no more gifts” ever again.

The toughness of the 1912 m (6273 ft) climb is well documented, and a constant stream of amateur riders flock to Provence to take on the challenge.

It would be folly, however, to talk about the Ventoux only in terms of the difficulty of the climb: the fast, difficult descent from the observatory on its summit down to the town of Malaucène on the Ventoux’s north side has also often played a key role at the Tour. Only when the Ventoux was first climbed, in 1951, did it go up from Malaucène. Every other time, it has been climbed from Bédoin.

The mountain featured on the Tour route for the fifteenth time in 2013. Stage 15 finished on its summit, so there was no descent this time, but, on the fifteenth stage of the 1994 Tour, Italian rider Eros Poli swept through Bédoin as a sole breakaway rider, and was faced with dragging his six-foot-four frame up the Ventoux’s terrible slopes. For such a big man, it was no mean feat, and by the time he’d struggled to the top, the 25-minute advantage he’d held over the chasers at the bottom had been cut to less than five.

A breakneck 21-km descent down to Malaucène, plus a further all-out 20-km effort to the finish in Carpentras, saw Poli come home as the day’s winner with a three-and-a-half minute advantage over the second-placed rider, fellow Italian Alberto Elli. It was a phenomenal achievement, and a rare instance of a rider getting the better of the Ventoux.

In 1967, defending Tour champion Lucien Aimar (left) also used the descent to similarly devastating effect. The Frenchman had in fact been with the tragic Simpson’s group on the climb when the Briton collapsed, and just a few minutes further on, Aimar fell victim to a puncture.

It left him two-and-a-half minutes off the pace of the front group at the top of the climb, and so began a manic, high-speed chase to get back on terms. Aimar did it, too, and was there in Carpentras to duke it out for the stage victory, won by Holland’s Jan Janssen. Aimar was fifth.

Later, one of the police motorbike riders came up to Aimar to tell him that he’d followed him down off the Ventoux – and had clocked him at 140 kph.

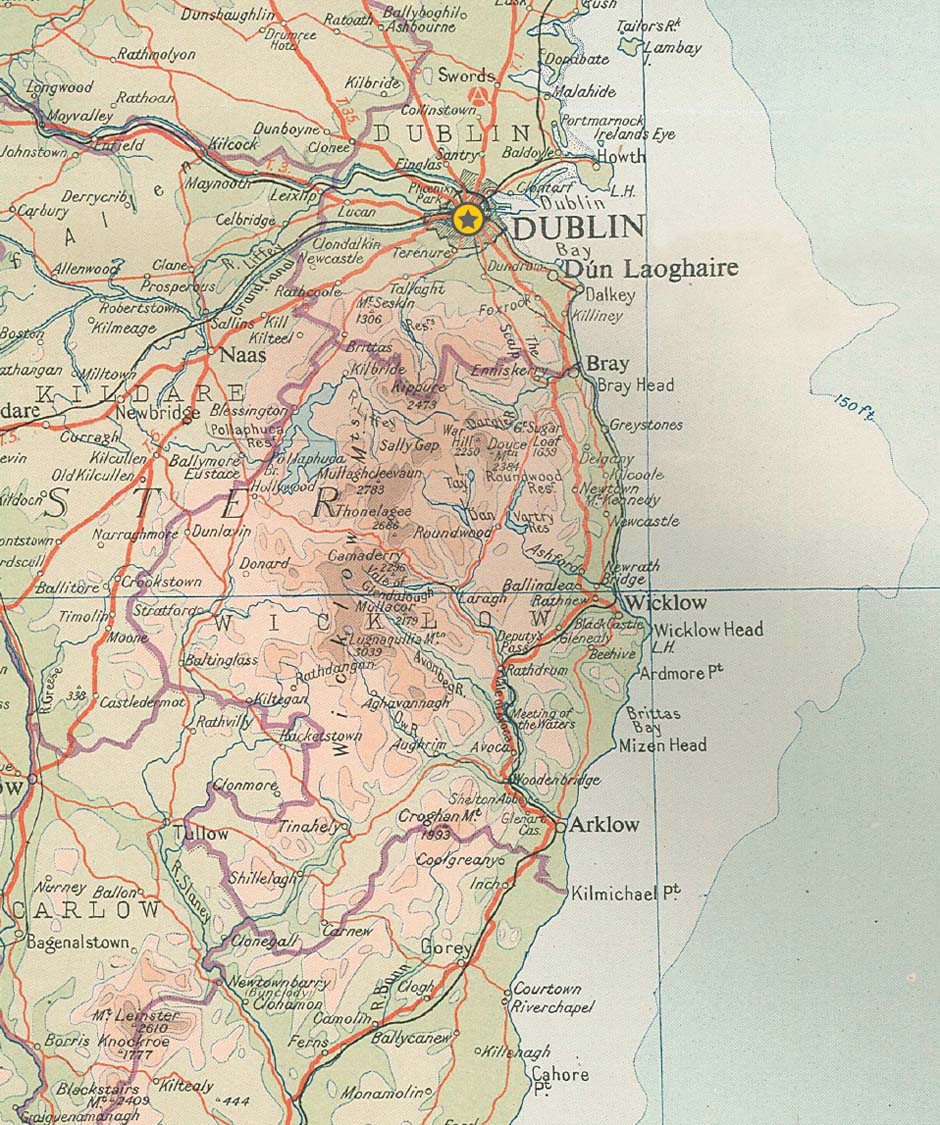

Dublin, Ireland

‘Doping was rife in professional cycling, and the red-blood-cell booster EPO – which dangerously thickened the blood in the arteries – was the drug of choice in the late 1990s’

Unfortunately for poor old Dublin, memories of the 1998 Tour de France’s Grand Départ there are more than a little spoiled by the seismic event that was the Festina Affair. When, three days before the start of the race, Belgian soigneur Willy Voet was apprehended by customs officers on the border between Belgium and France with a car-boot-load of illicit substances destined for the Festina squad in Ireland, it sent shock waves through the cycling world.

True, Voet wasn’t caught in Dublin, but it’s where the aftershocks were felt most keenly, and to say it put a dampener on proceedings is the understatement of the century.

This was an event that really kick-started the still-ongoing war against doping in cycling. It had had various false starts before: in the wake of Tom Simpson’s death as a result of drugs on Mont Ventoux at the 1967 Tour, and following the publication of A Rough Ride by former pro Paul Kimmage – himself an Irishman, as it happened – which blew the lid off doping in the sport, although it was a book taken nowhere near as seriously as it should have been when it appeared in 1990.

Voet being caught, and the falling of the Festina house of cards that followed, highlighted something too few had either dared, or had concrete proof of, to speak out about: doping was rife in professional cycling, and the red-blood-cell booster EPO – which dangerously thickened the blood – was the drug of choice in the late 1990s.

In a more positive link to Tour folklore, Dublin is also the birthplace of 1987 champion Stephen Roche. After a successful amateur career in France, Roche turned pro for the Peugeot team in 1981, and promptly beat Bernard Hinault to win the now-defunct Tour of Corsica.

In 1987, he won the Tour of Italy, then the Tour de France and then won the world road race championships in Austria to complete ‘the triple’.

He now runs a hotel in Antibes, near Nice, in France. His son, Nicolas, is also a pro rider who rides for Bjarne Riis’s Saxo-Tinkoff team.

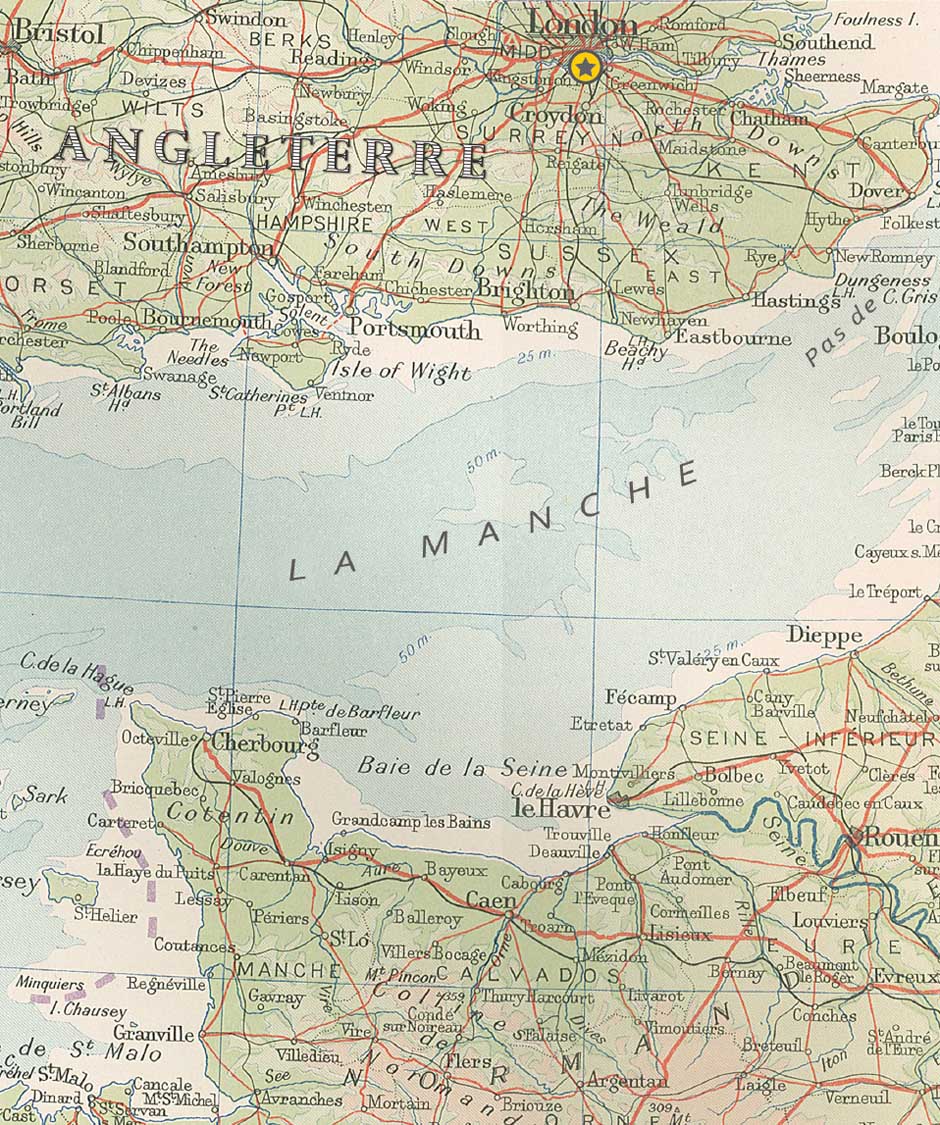

Normandy, France

‘I was in agony in the last 20 kilometres … It was horrible – I didn’t know where I was’

The French region of Normandy – or, rather, two regions: Upper and Lower Normandy – featured for the first time in the third edition of the Tour de France, in 1905, when Caen was both the finish of stage 10 and the start of the eleventh and final stage.

As well as retaining that quintessential Frenchness – it’s all picnic tables and boxes of wine when the Tour comes through, which is most years – Normandy has increasingly grown in popularity with British cycling fans, who make the trip across in their thousands, arriving at Cherbourg, Le Havre and Dieppe on the ferry, often with their bikes, to populate the roadside with their French cousins, and even share the wine when the Entente Cordiale allows.

In 2013, the Tour visits Mont-St-Michel – one of Lower Normandy’s most visited tourist attractions – for the stage 11 individual time trial. Prior to that, the island town’s first and last appearance on the route was in 1990, when it hosted the finish of stage 4 from Nantes – a bunch gallop won by young Belgian sprinter Johan Museeuw.

A year later, at the 1991 Tour, Normandy was on the route again. France’s Thierry Marie (left), a time-trial specialist of some repute, had done what he did best to win the race-opening prologue in Lyon. The next day, however, the leader’s jersey was lost to defending champion Greg LeMond after the morning’s road stage before moving to the young shoulders of Rolf Sørensen that afternoon following the team time trial.

When a crash forced Sørensen out of the race three days later, and LeMond gallantly refused to profit from the Dane’s misfortune, the 259-km sixth stage between Arras and Le Havre set off without a yellow jersey, and Marie decided that it was the ideal opportunity to try to seize it back for himself.

The Castorama chancer was a Normandy lad, too, so a few hours in front of his roadside fans and the TV cameras were going to do no harm at all, and he slipped off the front of the bunch 25 kilometres into the stage.

Fast forward six hours and, having at one point held a massive 22-minute lead, Marie still held a slim advantage over the chasing peloton.

“I was in agony in the last 20 kilometres,” said Marie. “It was horrible – I didn’t know where I was.”

Nothing for it, then, but to belt out Normandy ‘anthem’, Ma Normandie, grit his teeth, and hope to hold on for as long as possible.

His singing, picked up by the cameras, boosted him from regional to national hero, while the 234 km he spent alone ahead of the field before winning in Le Havre made it the second-longest successful breakaway in the race’s post-war history, after compatriot Albert Bourlon’s 253 km between Carcassonne and Luchon in the 1947 Tour.

Marie had clung on to win by just shy of two minutes, but it was also a case of mission accomplished when it came to the yellow jersey: the daring raid had given the Frenchman back the race lead, too, if only for two more days.

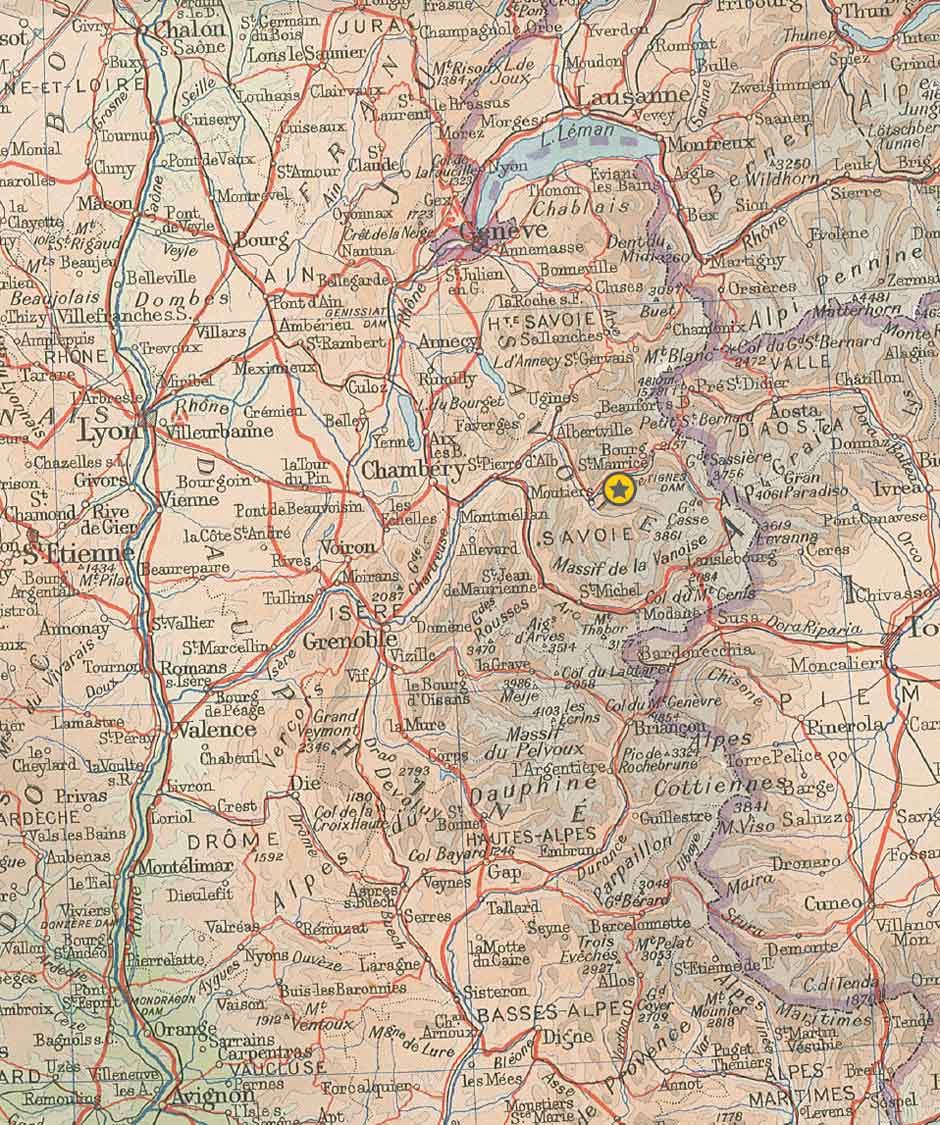

La Plagne, France

‘The oxygen mask required after his effort showed that it was the climb that had the last laugh’

“Just who is that rider coming up behind?” Phil Liggett asks the TV audience watching at home. “Because that looks like Roche. That looks like Stephen Roche … It’s Stephen Roche!”

The genuine surprise in the cycling commentator’s voice is impossible to mask. Stephen Roche, who would go on to win that 1987 Tour de France, saved his race there on the final climb up to the finish of stage 21.

Roche’s main rival that year, Pedro Delgado (above) – who was already in yellow, and leading the Irishman by 25 seconds going into the stage – had attacked at the bottom of the climb and, with Roche (above left) unable to respond, it looked as though the Spanish rider was going to sew the Tour victory up.

Roche dug deep, however, and by the top he’d managed to reduce the deficit to just 4 seconds. By stealing back a few seconds from Delgado on a climb-filled day the next day, and then beating him by just over a minute in the time trial on the penultimate day, it was Roche who won the race overall in Paris, by just 40 seconds.

Despite Roche’s fightback, you can’t exactly say that the Irishman ‘owns’ La Plagne. In fact, the oxygen mask required after his effort showed that it was the climb that had the last laugh.

Laurent Fignon, though – he’s a rider you can say conquered the mountain. He’s done it twice, too – which is 50 percent of the time that the Tour has visited the climb. Although everyone remembers Roche – and, more specifically, Liggett’s commentary – La Plagne has only been used by the Tour four times.

The first time the climb was used – in 1984 – Fignon already had the race sewn up, but it didn’t stop him taking the stage victory and more than a minute out of his closest rivals.

In 1987, too, it was Fignon who took the stage win, outsprinting Spain’s Anselmo Fuerte, although it was somewhat overshadowed by Roche’s heroics. Admittedly, by that point in the race Fignon was well off the pace, more than 15 minutes down on Delgado. The Frenchman’s ’83 and ’84 overall Tour wins must have seemed like another era by then, although it turns out they weren’t, really: Fignon battled back to fitness to contend for the title in 1989, but was pipped by Greg LeMond for that year’s win by 8 seconds.

London, United Kingdom

‘Warm temperatures, perfect blue skies and huge, enthusiastic crowds … Many of the riders talked afterwards of their shock and surprise at what a fantastic reception they received’

So astonishing was the London weather that accompanied the 2007 Tour’s Grand Départ in the UK capital, it was as though the tourist board had done some kind of a deal with someone important. Warm temperatures, perfect blue skies and huge, enthusiastic crowds met the magnificent men and their riding machines; many of the riders talked afterwards of their shock and surprise at what a fantastic reception they received, while the Tour organisation promised that they’d be back.

Contrast that 2007 experience with the first time the race had visited British shores in 1974, which was, in fact, the first time that the race had headed out of mainland Europe. Then, in Plymouth, the Tour raced up and down the newly built Plympton bypass, and no one – neither the press nor the public – paid it much attention. There was only one happy rider on that occasion, and that was stage winner Henk Poppe.

The Tour came to British shores again in 1994, which was a much happier occasion. London still wasn’t on the route, but thousands of spectators enjoyed a stage between Dover and Brighton, and then a stage on the second day based around Portsmouth.

However, just seven years after last hosting the start of the Tour, London will feature again in 2014 when Yorkshire – and, more specifically, Leeds – hosts the Grand Départ. That opening stage will finish in Harrogate, while a second stage – York to Sheffield – will stay in Yorkshire before London hosts the finish of the third stage, starting in Cambridge.

Armed with even more knowledge and experience than ever before in the wake of sprinter Mark Cavendish’s twenty-five stage wins since 2008, as well as Bradley Wiggins’s and Chris Foome’s overall victories in 2012 and 2013, the public reaction and turnout in Yorkshire is certain to be nothing short of spectacular. The London Olympics, meanwhile, proved what hunger there is for road cycling in the capital – as if the 2007 Tour start there hadn’t been proof enough already.

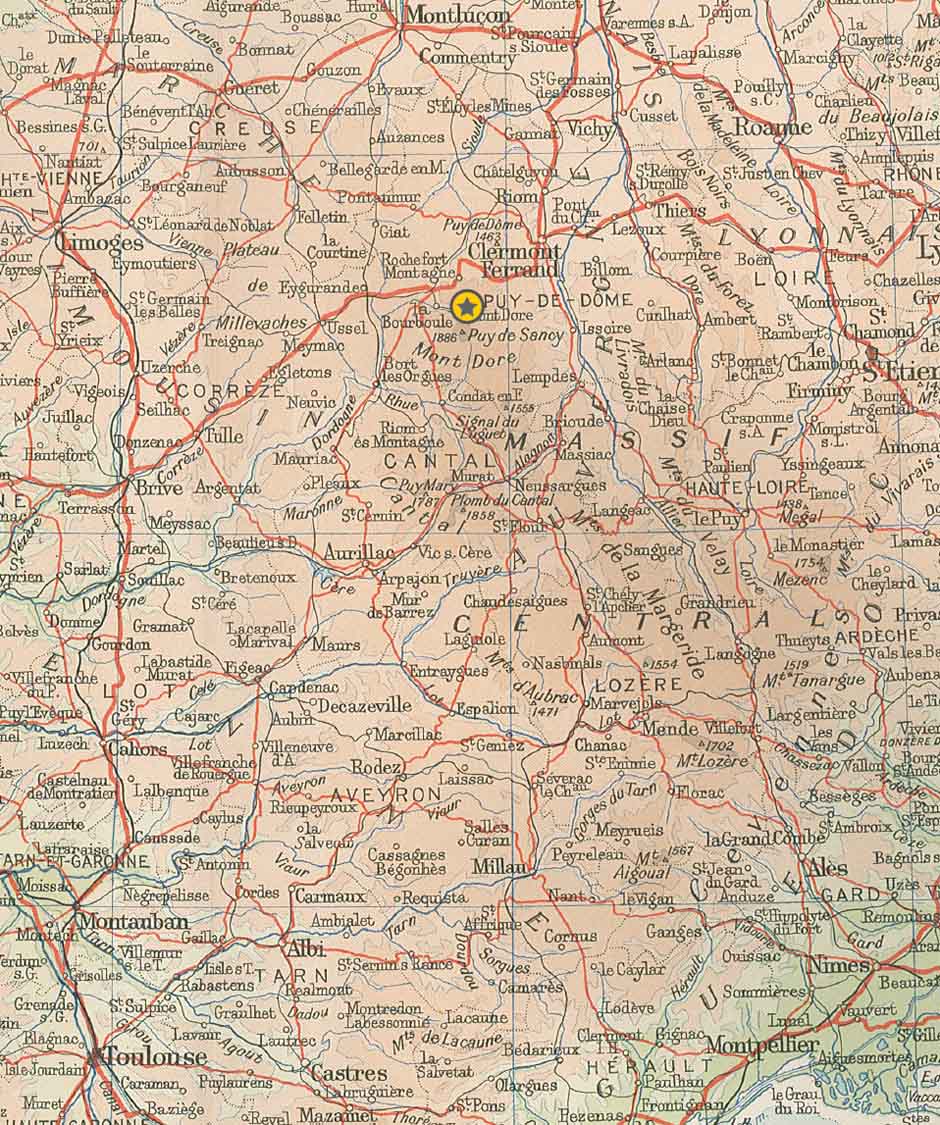

Puy de Dôme, France

‘The two rivals matched each other pedal-stroke for pedal-stroke before Poulidor pulled away, although it was Anquetil who got the last laugh, winning his fifth and final Tour that year’

The Puy de Dôme, an extinct volcano in the Massif Central, has seen its fair share of ‘Tour moments’ – mainly thanks to its narrow road leading to the summit at 1415 m (4642 ft).

The climb reaches a maximum gradient of 13 percent on its upper slopes, and it was there that Raymond Poulidor put 42 seconds into rival Jacques Anquetil at the 1964 Tour. The famous photograph of their shoulder-to-shoulder tussle lower down the climb is perhaps one of the best-known Tour images; the two rivals matched each other pedal-stroke for pedal-stroke before Poulidor (above) pulled away, although it was Anquetil who got the last laugh, winning his fifth and final Tour that year.

In 1975, the next man to win five Tours – Eddy Merckx – was possibly robbed of a sixth victory thanks to the Puy de Dôme. The narrow roads meant that the feverish crowd was virtually on top of the riders, and the Belgian was dealt a punch in the kidneys by a spectator. Merckx was already in pursuit of Bernard Thévenet at that point – was the spectator a supporter? – and it was the Frenchman who went on to release the stranglehold Merckx had held on the Tour by beating the Belgian by 2 minutes 47 seconds in Paris.

The climb was first used by the Tour in 1952, and has been used twelve times since then, and for the last time in 1988. The sheer size of the Tour today means that the organisation has struggled to take the race there since – there’s very little room at the car park at the top – but there are a number of people who would like to see them find a way.

The Puy de Dôme remains a lesser-known climb compared to Alpe d’Huez, the Tourmalet or Mont Ventoux, and that’s because it’s a private road, which isn’t permanently open for riders to challenge themselves. However, the battles played out on the climb’s slopes, and photographs like the one of Anquetil and Poulidor, have cemented its place in Tour history.

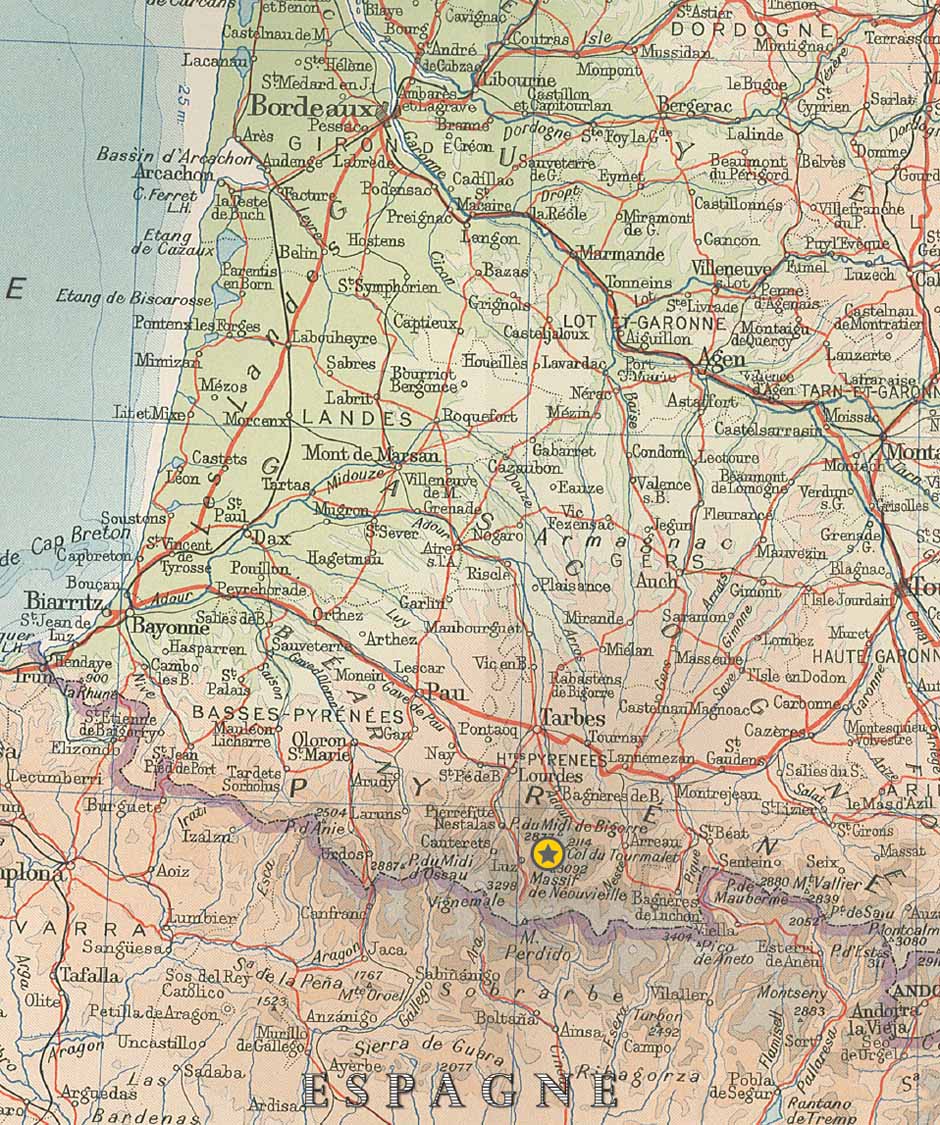

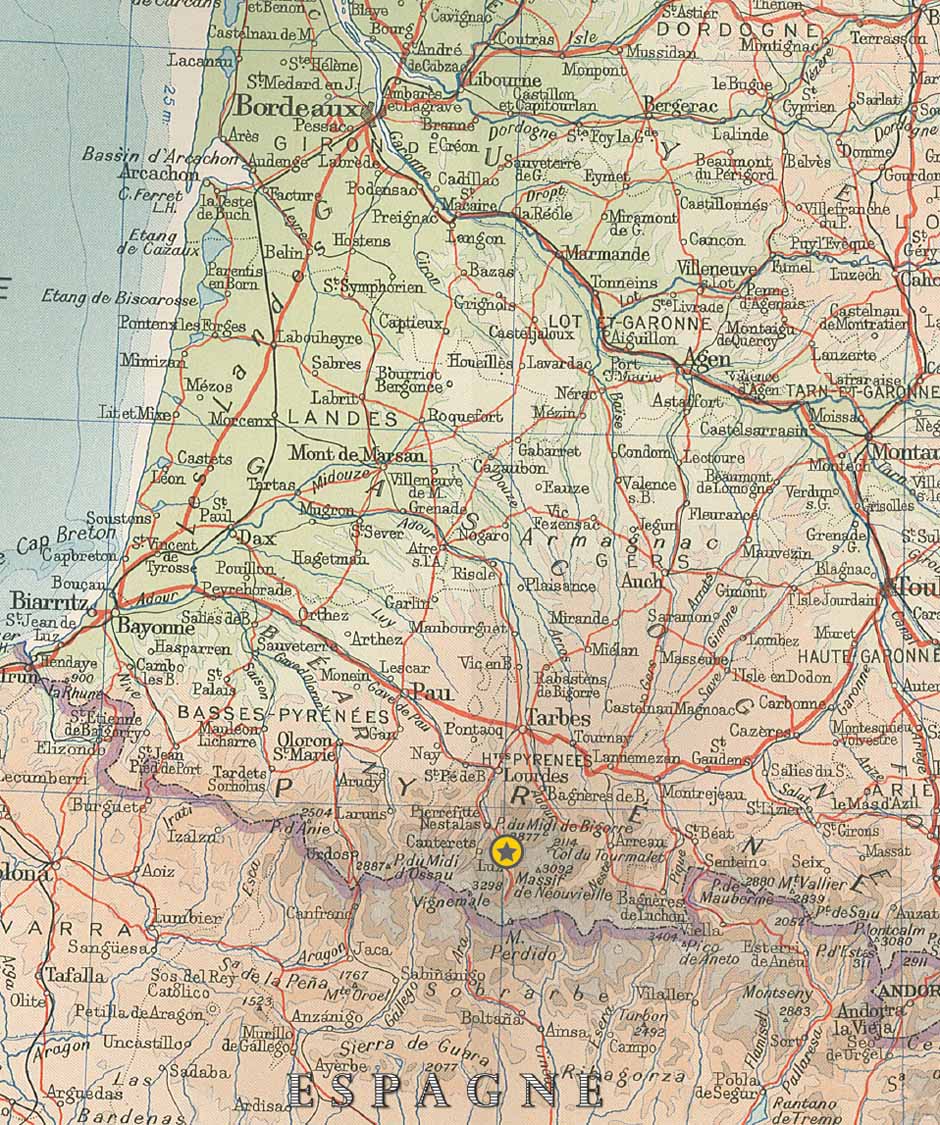

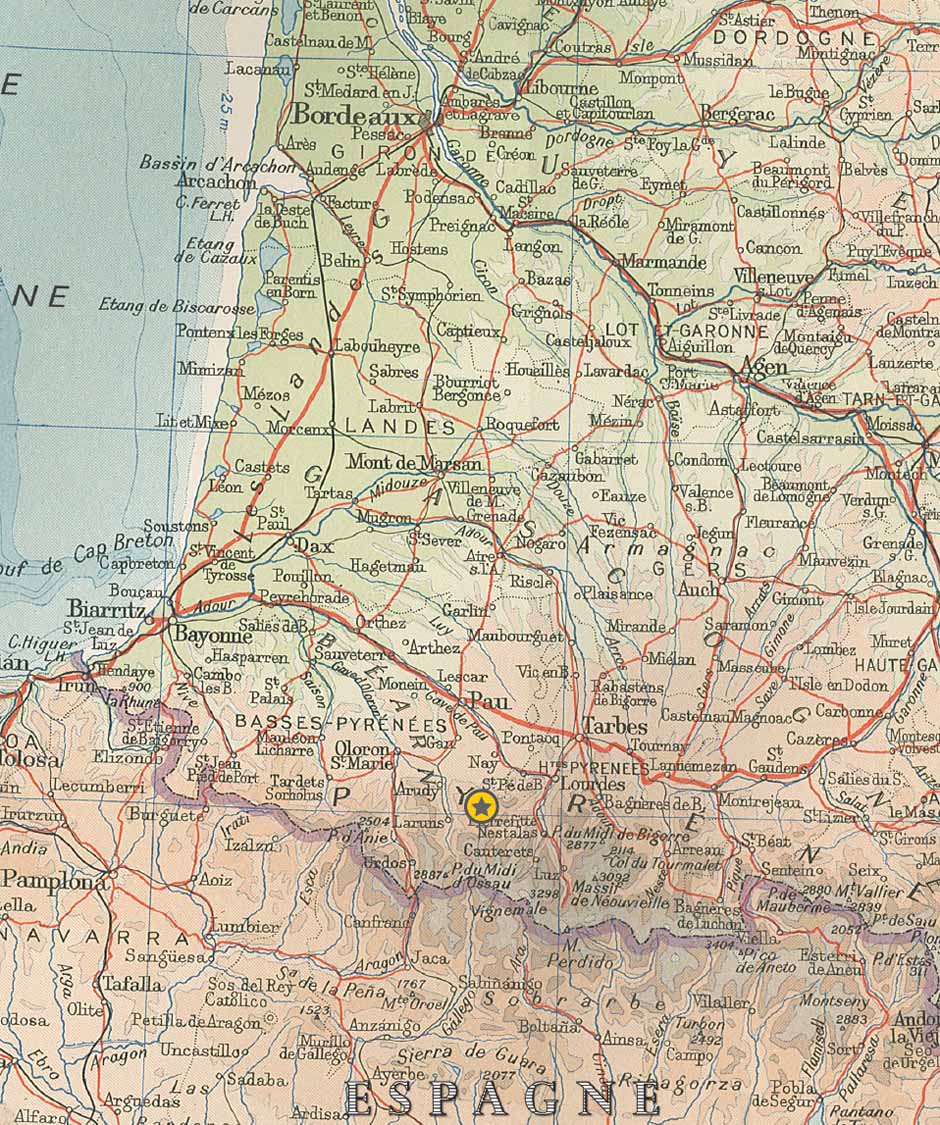

Col du Tourmalet, France

‘It dominates the Pyrenees, but it dominates the riders, too, when they encounter it’

The Col du Tourmalet is a climb inextricably linked with the Tour de France. It’s the most-used climb in the race, having made seventy-eight appearances on the route since its debut in 1910. It’s almost hard not to go over it: geographically, it dominates the Pyrenees, but it dominates the riders, too, when they encounter it, whether that be from the western side from the town of Luz-St-Sauveur or the eastern side from Ste-Marie-de-Campan, via the ski town of La Mongie.

Octave Lapize, the French winner of the 1910 edition, was first to trudge over the Tourmalet’s summit, but it had clearly taken its toll: he was the one who, after cresting the next climb on the day’s agenda – the Col d’Aubisque – accused the race organisers of trying to kill the riders with the inhumanity of taking the Tour into the Pyrenees for the first time.

The Tourmalet became part of Tour history after then race organiser Henri Desgrange’s assistant, Alphonse Steines, was tasked with checking out the viability of using the Pyrenees on the race route. January perhaps wasn’t the best time to take a look at the mountains, but Steines ignored the dangerous snowstorms he encountered to tell Desgrange that the climbs should definitely be included on the route.

Even without the snow in the summer months, the Tourmalet and its surrounding neighbours still provided more than a stiff challenge due to their gradients and, even more importantly, the fact that the roads were still unmade in those days.

At the 1913 Tour, Eugène Christophe broke his forks on his way down the eastern side of the Tourmalet. There was nothing for him to do but run down the rest of the descent with his bike where he made repairs at a blacksmith’s in Ste-Marie-de-Campan. Despite his efforts, he was subsequently penalised for having used outside assistance – the blacksmith’s assistant had operated the bellows for Christophe to make the repairs to his forks himself.

Both routes up to the summit at 2115 m (6939 ft) are tough, which means that the descents off the top in both directions are equally tough – whether you’re running down with a broken bike, à la Christophe, or, more conventionally, are on your bike: cycling commentator Paul Sherwen said he once saw fellow British rider Sean Yates’s cycling computer after a descent off the Tourmalet, and it read that his maximum speed had been 112 kph.

Alpe d’Huez, France

‘In 1986, La Vie Claire team-mates Greg LeMond and Bernard Hinault called a truce to their rivalry, crossing the line together’

Alpe d’Huez was first used by the Tour in 1952. The late, great Fausto Coppi won the stage – and that year’s Tour – and its semi-regular place as one of the race’s most decisive and best-loved climbs was sealed.

If mountains can have rivals, then Mont Ventoux is definitely Alpe d’Huez’s bête noire. It’s in terms of the public’s affections that the two behemoths war, and in 2013 both climbs featured on the Tour route, although the argument as to which one is ‘better’ remains undecided.

‘The Giant of Provence’ certainly has a darker reputation as the site of British rider Tom Simpson’s death in 1967; however, the Ventoux shouldn’t take all the bad rap – Alpe d’Huez was where, in 1978, Belgian Michel Pollentier failed a dope test – or, rather, was caught trying to pass it – with the use of a concealed pouch of ‘clean’ urine under his armpit, with a tube running down to his shorts.

Luxembourg’s Frank Schleck has both good and bad memories of the Alpe. In 2006, Schleck’s attacking style netted him the stage win from Italy’s Damiano Cunego. Two years later, Schleck arrived at the base of Alpe d’Huez in the yellow jersey – only to have to witness his CSC team-mate Carlos Sastre attack. While the plan was for Frank and brother Andy to police any riders giving chase, Sastre was simply too strong, and rode away to the stage win, the yellow jersey and the Tour victory, while the Schlecks could only watch.

Arguably the best remembered day on the Alpe was in 1986 when the Tour’s top two riders – La Vie Claire team-mates Greg LeMond and Bernard Hinault – called a truce to their rivalry, crossing the line together (below). Hinault had won the 1985 Tour with LeMond’s help; this time it was LeMond’s turn to take the overall victory in Paris.

The Tour’s two ascents of Alpe d’Huez on stage 18 in 2013 provided a worthy winner in the shape of Frenchman Christophe Riblon, but in 2011 the climb featured as the finale of a short, 109-km stage from Modane, tackling first the Col du Télégraphe, then the Col du Galibier and then the Alpe. It proved to be a veritable fireworks display as Alberto Contador rediscovered his lost form, Cadel Evans had his work cut out containing the Schleck brothers and Thomas Voeckler fought in vain to retain a podium spot, with his faithful Europcar team-mate Pierre Rolland announcing himself as a star of the future by being allowed to ride his own race and take a prestigious stage victory.

Col de Portet d’Aspet, France

‘Two days later, Casartelli’s team-mate, Lance Armstrong, took an emotional stage victory in Tarbes. He had time to celebrate his win, although it was no ordinary celebration. Instead, the American pointed to the sky, and it was Casartelli’s life that was celebrated’

The Col de Portet d’Aspet (below) first featured in 1910 – the year that the first Pyrenean climbs appeared at the Tour. The Portet d’Aspet was climbed on stage 9 – the day before the Col du Tourmalet’s first appearance – and first over the top was France’s Octave Lapize, who also won the stage, and the Tour overall in 1910.

Unfortunately, despite having appeared on the Tour route twenty-nine times (it was last used in 2011), the Portet d’Aspet is best remembered for when it appeared in the 1995 Tour. In 1973, Raymond Poulidor was seriously injured after a crash on the descent of the Portet d’Aspet. It helped to give it a reputation as a mountain with an extremely dangerous descent.

Stage 15 of the ’95 Tour took the riders over the Portet d’Aspet, the Col de Menté, the Peyresourde, the Aspin and the Tourmalet before a summit finish at Cauterets.

A lone win by Richard Virenque was overshadowed when news filtered through of a crash on the descent of the first climb. Fabio Casartelli – an Italian riding for the American Motorola outfit – went down with a number of other riders. But while they escaped serious injury, Casartelli hit a concrete barrier at the side of the road.

Just the evening before, the 1992 Olympic road race champion’s mother had warned him to wear his helmet. He chose not to, and although it can never be proved whether a helmet might have saved his life, Casartelli died as a result of the head injuries he sustained in the impact.

His Motorola team-mates were allowed to take all the prize money the next day, which was given to Casartelli’s family, and those same team-mates crossed the finish line in Pau at the head of a neutralised stage.

Two days later, Casartelli’s team-mate, Lance Armstrong, took an emotional stage victory in Tarbes. He had time to celebrate his win, although it was no ordinary celebration. Instead, the American pointed to the sky, and it was Casartelli’s life that was celebrated.

A monument now stands at the point at which the Italian died, and on each of the ten occasions that the Tour has revisited the climb, the race has paid its respects.

Luz-Ardiden, France

‘Its toughest sections come halfway up the climb, where the gradient touches 9 percent’

The 2003 Tour was the first to see Lance Armstrong really suffer on the way to his seven now-taken-away titles. That edition was his fifth victory at the time, matching Miguel Indurain’s five consecutive titles, and equalling the number of Tours won by Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx and Bernard Hinault, but it didn’t come easy.

Climbing alongside Spain’s Iban Mayo on the lower slopes of Luz-Ardiden, on the day’s final climb of stage 15 from Bagnères-de-Bigorre, Armstrong’s handlebars caught in a spectator’s bag, and he was dumped to the ground, taking Mayo (below right) with him.

The American’s main rival that year, Germany’s Jan Ullrich, at first appeared to push on, but then clearly took a look back to see what was going on, and waited for Armstrong, who almost came a cropper once more after pulling his foot out of the pedal while pushing hard to make it back up to the front group.

Once Armstrong was safely back with the leaders, Mayo attacked, and Armstrong went with him, then pushed on alone to win the stage by 40 seconds, increasing his overall lead to over a minute from Ullrich.

It was also on Luz-Ardiden at the 1990 Tour that Indurain announced himself to the world. From 1991 to 1995, the Spaniard was a dominant force, but in 1990 the tall climber-cum-time-trial-specialist matched defending champion Greg LeMond pedal-stroke for pedal-stroke. LeMond had turned the screw tight enough at the bottom of the climb to shed yellow-jersey-wearer Claudio Chiappucci from the front group, and then ramped up the speed with only Indurain and Marino Lejarreta still for company. Lejarreta was the next to drop, leaving only Indurain, who looked like a man simply biding his time as he sat calmly on the road-race world champion’s wheel.

Hordes of fans – many of them Spanish, this being the Pyrenees – roared their young compatriot on to victory. With 400 metres to go, Indurain went to the front and, with a cursory glance behind at the 1989 Tour winner, pushed on for the stage win – and the start of something bigger. LeMond pushed hard all the way to the line, finishing 6 seconds behind Indurain, while taking well over two minutes from Chiappucci, although the Italian still led by 5 seconds overall from LeMond, who would have his opportunity to close the gap a few days later on the time-trial stage at Lac de Vassivière.

Luz-Ardiden may not be that difficult a climb – its toughest sections come halfway up the climb, where the gradient touches 9 percent – and it has only featured on the route eight times, but Armstrong’s 2003 fall (a rare occurrence during his riding career), LeMond’s vital effort to win the 1990 Tour and Indurain’s coming-of-age that day mark it out as an important battleground in the Tour’s history.

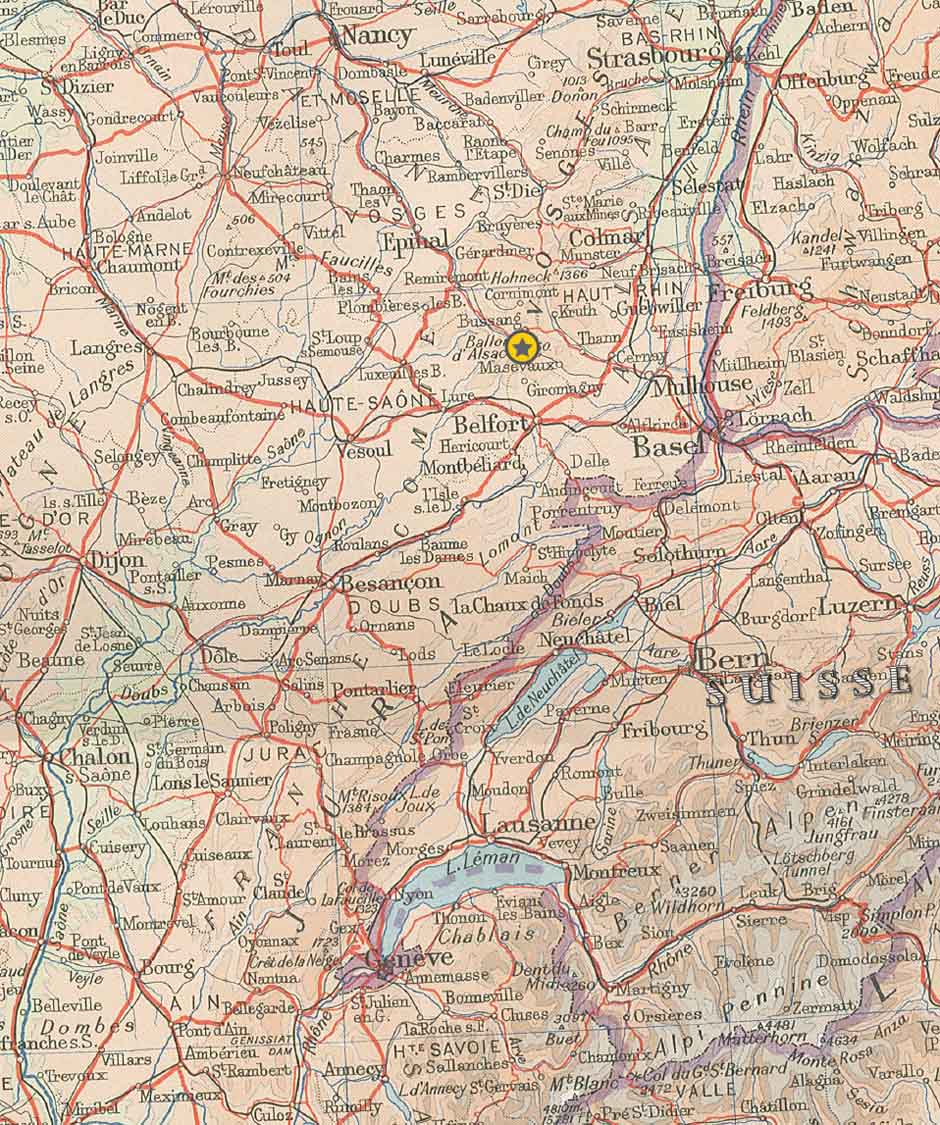

Ballon d’Alsace, France

‘It was a challenge that the organisers hoped would prove to be a major obstacle. No one was expected to be able to make it to the top without walking’

The Ballon d’Alsace, in the Vosges mountains of northeast France, is widely considered to be the first climb used by the Tour, but that simply isn’t the case. True, you could call it the first major climb to be included on the route, in 1905, but the very first stage of the very first Tour, in 1903, featured the Col des Echarmeaux and the Col du Pin-Bouchin – admittedly much smaller climbs than the Ballon d’Alsace – while on stage 2 the same year the riders had to scale the Col de la République, which, at 1161 m (3809 ft), was pretty close to the Ballon d’Alsace’s 1178 m (3865 ft).

The 1904 Tour followed the same route as in 1903, so again those three climbs featured on the route. The Ballon d’Alsace was to follow in 1905, on stage 2 between Nancy and Besançon, and it was a challenge that the organisers hoped would prove to be a major obstacle. No one was expected to be able to make it to the top without walking, but René Pottier proved everyone wrong by grinding his way to the top first. It took its toll, though; Pottier later faded, and the day’s stage winner in Besançon was Hippolyte Aucouturier. Pottier quit the race the next day, but returned in 1906 to win the whole thing.

The Tour has always favoured the climb from St-Maurice-sur-Moselle in the north, from where the climb averages 6.9 percent. Indeed, it was from the same town that the 1967 Tour tackled the Ballon d’Alsace, but it was also to be its first summit finish there. The defending Tour champion, Lucien Aimar, went on the offensive, and won the stage that time, while another summit finish there in 1969 was won by a certain Eddy Merckx (below) – the young Belgian’s first ever Tour stage victory.

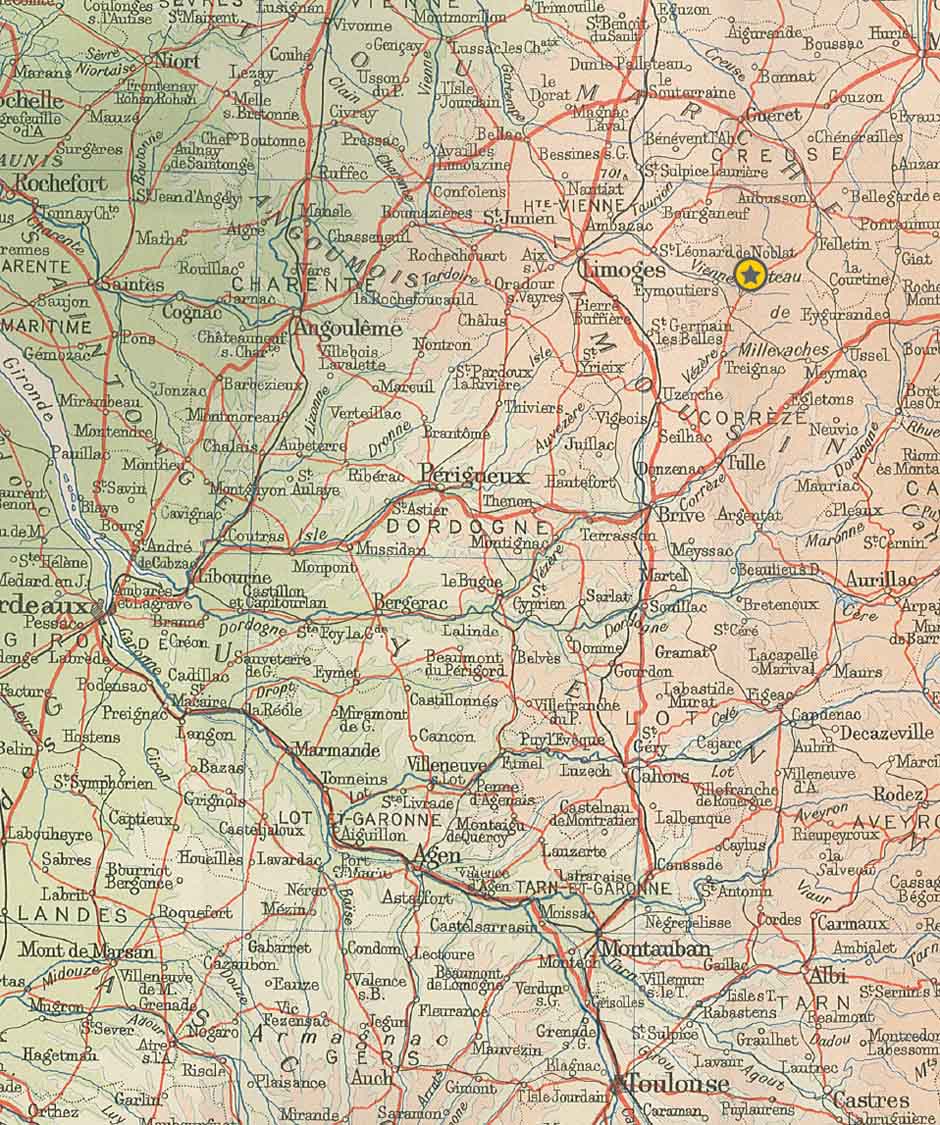

Lac de Vassivière, France

‘The roads surrounding it are perfect for a time-trial stage of the Tour de France’

Lac de Vassivière, in the Limousin region, is one of France’s largest man-made reservoirs – and the roads surrounding it are perfect for a time-trial stage of the Tour de France.

At the 1990 Tour, eventual race winner Greg LeMond had chased Claudio Chiappucci across most of France with the Italian left as the last man standing from a first-stage breakaway that had gained over 10 minutes, and the defending champion was still trailing Chiappucci by 5 seconds going into the penultimate stage at Lac de Vassivière.

There were shades of the final stage of the 1989 Tour in Paris the year before when the American had needed to – and managed to – close a gap on Laurent Fignon to win the race. LeMond, resplendent in his road-race world champion’s skinsuit – this was still in the days before the introduction of a separate time-trial world championship, – and a pair of ‘clip-on tri bars’, set to work. This time, the 5-second deficit to Chiappucci seemed much more within reach, and so it proved.

Also counting in LeMond’s favour had been the fact that he knew the route well, having ridden a stage of the 1985 Tour there – also run as a time trial – which he won, funnily enough, by 5 seconds from Bernard Hinault. It was a kick in the teeth for Hinault, who was LeMond’s team leader, but the American’s assistance during the rest of the race ensured that Hinault tied up a fifth Tour title, which remains the last by a French rider. The stage win was ample compensation for LeMond in any case: it made him the first American winner of a Tour stage.

In 1995 – the third and still the last time that the Tour has visited the lake – Miguel Indurain (above) stamped his authority all over it by winning the stage there, which was again held as a time trial. Already in yellow, the Spaniard sewed up his fifth Tour title by increasing his lead to 4 minutes 35 seconds over Switzerland’s Alex Zülle in second place overall. Ominously, the rider who finished in second place on the stage, just 48 seconds off the pace, was Bjarne Riis – inching ever closer to Indurain, it seemed. Riis finished third in Paris behind Indurain and Zülle in 1995; a year later, the Dane was to oust Indurain altogether.

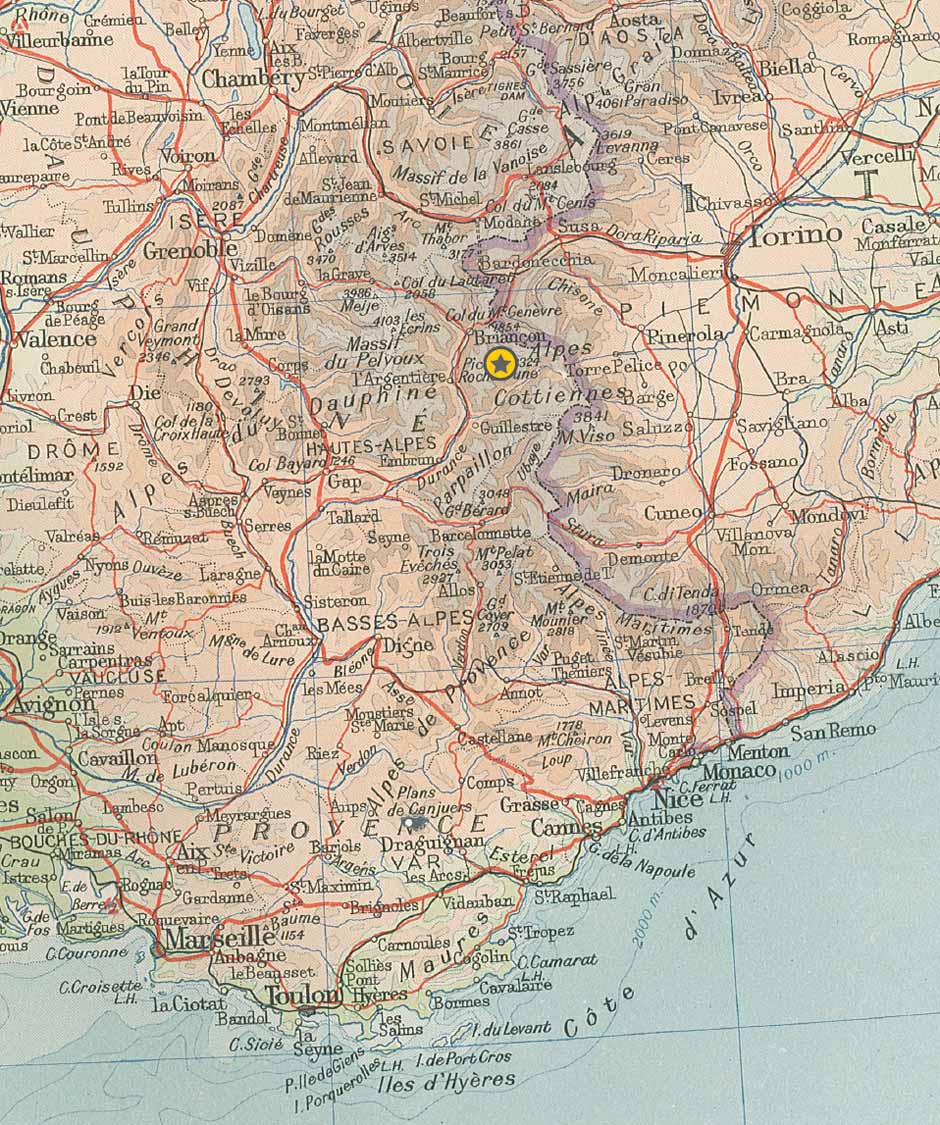

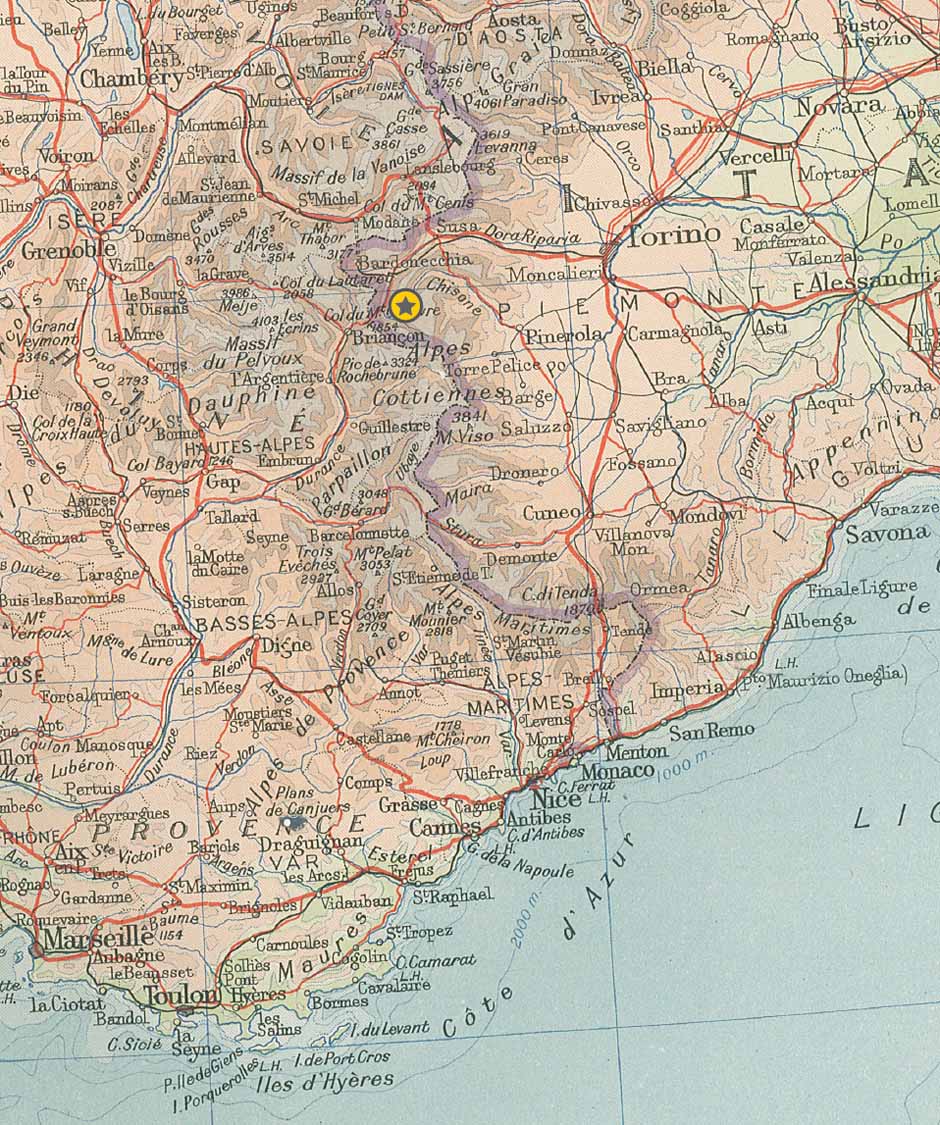

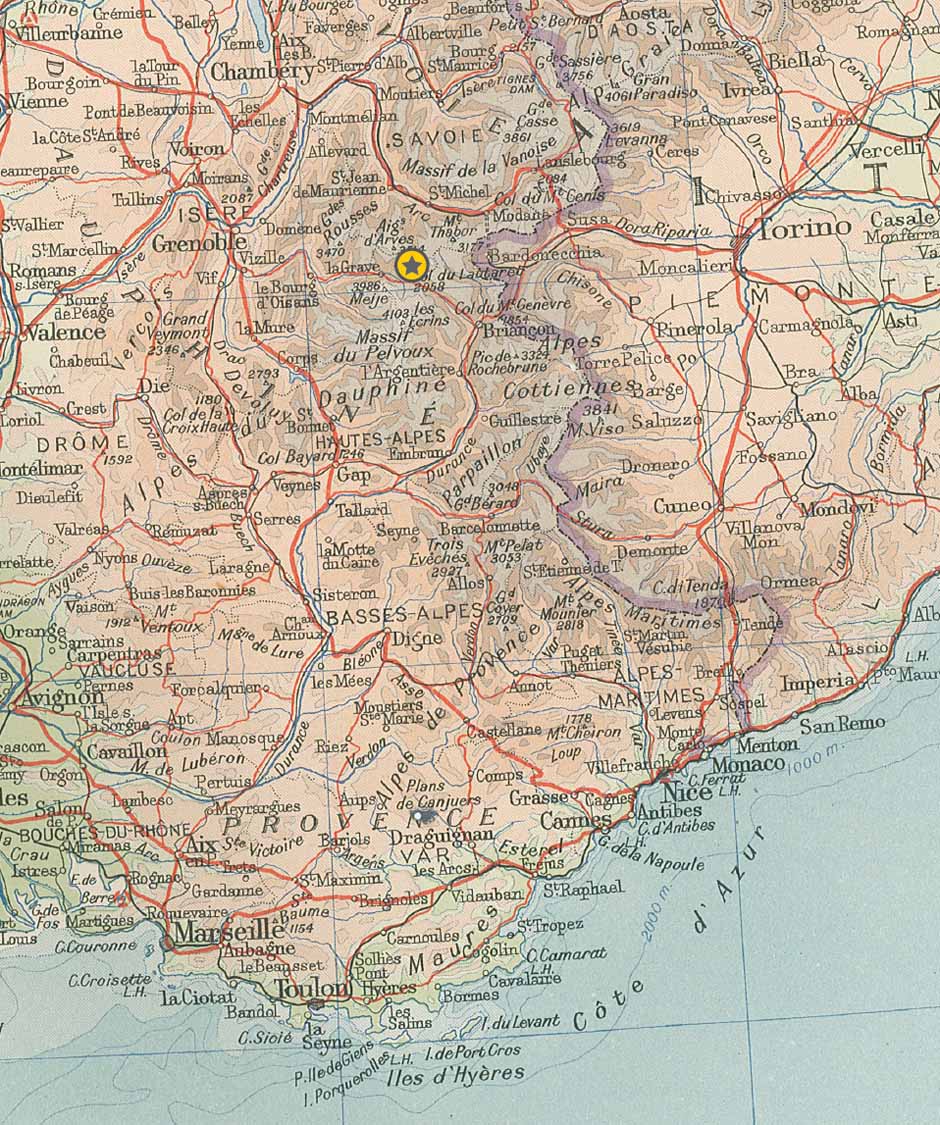

Col d’Izoard, Frances

‘In the Casse Déserte is one of the more haunting monuments … silent and windswept, with a very real sense of the battles man and machine, combined, have had against the forces of nature’

The most iconic images of the Col d’Izoard are those of lone riders struggling up through the moonscape of the Casse Déserte section of the climb, on its southern side, from Guillestre. It’s here, around two kilometres from the summit, that you’ll also catch a glimpse of the memorial to Italy’s Fausto Coppi and Frenchman Louison Bobet – names both synonymous with the climb – whose profiles are mounted on plaques, mounted in turn to one of the many jagged rocks. Along with the memorial to Fabio Casartelli on the Col de Portet d’Aspet and the one in honour of Tom Simpson on Mont Ventoux, the Coppi/Bobet one in the Casse Déserte is one of the more haunting monuments to riders past that can be found in the Alps and Pyrenees. Part of it, of course, is due to the legend of the riders concerned, but an equal part is the location – silent and windswept, with a very real sense of the battles man and machine, combined, have had against the forces of nature.

In 1949, on stage 16 from Cannes to Briançon, the Izoard was the site of a duel between Coppi and compatriot Gino Bartali, who rode together up through the Casse Déserte and on down the other side to Briançon, where Bartali took the stage win and Coppi, later, the overall Tour title.

A year later, Coppi was a non-starter at the Tour with a broken pelvis sustained at the Giro, while Bartali pulled himself and the entire Italian team out of the race midway through after complaining of feeling threatened by French fans.

That opened the door to the start of Bobet’s relationship with the Izoard and, with no Coppi or Bartali to get in the way, the Frenchman used the Izoard as a springboard to win stage 18 between Gap and Briançon. Switzerland’s Ferdi Kübler and Belgium’s Constant ‘Stan’ Ockers were the only riders capable of finishing within three minutes of Bobet, and Kübler went on to win that 1950 Tour with some ease.

The stage between Gap and Briançon over the Izoard was key in 1953, during which Bobet rode alone up the climb to finish over five minutes ahead of Holland’s Jan Nolten. Bobet won his first Tour that year, and the Izoard played just as important a role the next year when Bobet won the second of his three Tours. Bobet won again in Briançon on stage 18 thanks to his knowledge of ‘his’ mountain, although that man Kübler finished only 1 minute 49 seconds behind on that occasion.

Col d’Aubisque, France

‘Van Est’s front wheel slipped on the wet first corner while descending off the mountain, and he skidded off the barrier-less road.

It was truly miraculous that he didn’t plunge to his death’

In 1985, the Col d’Aubisque featured as the final climb in what was a relatively short stage of 52 km from Luz-St-Sauveur to the summit of the Aubisque, which also took in the Col du Soulor.

Stephen Roche arrived in Luz-St-Sauveur that morning meaning business and wearing a skinsuit, rather than a standard, separate jersey and shorts, proving that modern-day usage by David Zabriskie and Team Sky is nothing new. Zabriskie talked of sniggers when he turned up for the start of Paris-Tours in 2008 wearing a skinsuit in order to give himself every aerodynamic advantage, and eyebrows have been raised at Sky often plumping for one for road racing in the past couple of years, so you can only imagine the kind of reception Roche got in the mid-1980s.

It worked, though – Roche won that stage to the top of the Aubisque. Two years later, Roche would be winning the Tour overall.

The 1709-m (5607-ft) Aubisque first featured in the Tour on 1910. On that occasion Octave Lapize famously rode over the top accusing the race organisers of being murderers, such was the severity of the climbs in the Pyrenees that had been introduced that year.

In 1951, Dutchman Wim Van Est (right) struggled going down the Aubisque more than going up. Clad in the yellow jersey as Tour leader, Van Est’s front wheel slipped on the wet first corner while descending off the mountain, and he skidded off the barrier-less road. It was truly miraculous that he didn’t plunge to his death, saved instead by a precipice ‘just’ 70 m down the ravine. No one had a rope long enough to reach him, so instead his manager strung together all forty of the team’s tyres, which were used to haul him back up to safety.

Sestriere, Italy

‘It was a seemingly suicidal move, but as the race headed across the border, and the roadside fans turned from French to Italian, you began to sense that Chiappucci was onto something special’

The ski resort of Sestriere sits just over the border from France in Italy, and has been the scene of some truly epic Tour de France stages.

In 1992, Claudio Chiappucci – who’d risen to prominence on the back of having worn the yellow jersey at the 1990 Tour, holding off eventual race winner Greg LeMond until the penultimate stage – attacked early on stage 13 from St-Gervais-les-Bains, on the Col des Saisies. By the Col de l’Iseran, the breakaway group was down to just the Italian and France’s Richard Virenque, whom Chiappucci (below) promptly dropped, pushing on alone, dressed in the polka-dot ‘king of the mountains’ jersey.

It was a seemingly suicidal move, but as the race headed across the border, and the roadside fans turned from French to Italian, you began to sense that Chiappucci was onto something special. Even the Italians – who will always favour their beloved Giro – knew what the Tour’s polka-dot jersey signified. Chiappucci really was king of the mountains that day, and the crowds on the final climb up to Sestriere were simply enormous, vociferous and seemingly unwilling to let Chiappucci and the phalanx of police motorbikes through until the very last moment. A spectacular stage culminated in the stage win for Chiappucci, but Miguel Indurain stood firmly enough to take a second overall Tour title.

In 1996, the finish of stage 9 in Sestriere saw Denmark’s Bjarne Riis take the yellow jersey for the first time in the race, and then defend it all the way to Paris. The snow-hit stage saw the route reduced to just 46 km (28.5 miles), missing out the originally scheduled climbs of the Col de l’Iseran and the Col du Galibier. Riis won alone at Sestriere, but we now know that it was medically assisted: he admitted in 2007 to having used EPO during his riding career, which feels a lot like a kick in the teeth for Sestriere, almost devaluing a climb renowned for epic acts of attacking riding – all the more so when you consider that Lance Armstrong won alone there in 1999, effectively sewing up his first Tour title.

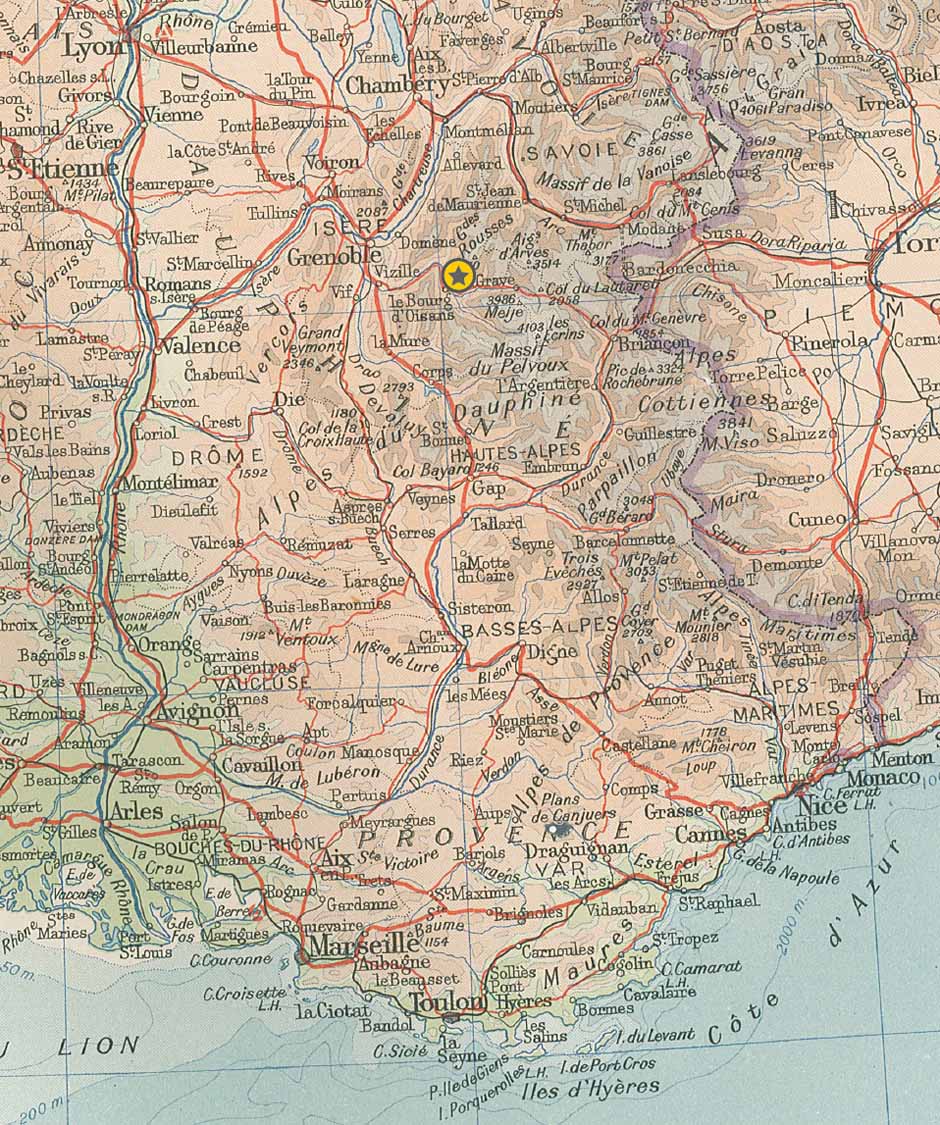

Col du Galibier, France

‘On the menu was the giant that is the Col du Galibier. At 2556 m (8386 ft), it was by far the highest pass the race had used’

Having included the Pyrenees for the first time in 1910, the Tour paid its first visit to the Alps the following year – and on the menu was the giant that is the Col du Galibier. At 2556 m (8386 ft), it was by far the highest pass the race had used, dwarfing the Pyrenees’ 2115-m (6939-ft)-high Col du Tourmalet.

The Galibier would feature on the Tour route, as the highest point, in every edition until 1938, when it was superseded by the introduction of the Col de l’Iseran (2770 m/9088 ft), although the Galibier still appeared on the same stage that year, and both climbs were there again in 1939.

After the Second World War, the Galibier featured in the next two editions, in 1947 and 1948, but has since been used sporadically – although still often. Since 1947 the climb has featured a further thirty-three times, making sixty-two appearances in all.

Before 1976, when the tunnel near the summit was closed for repair, the riders had crossed the top of the Galibier at 2556 m (8386 ft). Without the tunnel, however, a new road took the riders right up to 2645 m (8678 ft).

The Galibier should have featured in the 1996 Tour, but the climb’s altitude, and therefore its propensity for snow, meant that it was omitted from stage 9 between Val d’Isère and Sestriere due to it being unpassable along with the Col de l’Iseran. That shortened stage allowed Denmark’s Bjarne Riis to attack and punish his rivals to the tune of 30 seconds, while also gaining him the yellow jersey, which he then held all the way to Paris. Might the Galibier have slowed him down?

It certainly did for the runner-up that year, Riis’s young Telekom team-mate Jan Ullrich, in 1998. Having usurped Riis to win the 1997 Tour, Ullrich was up against Italy’s Marco Pantani the following year, and ‘The Pirate’ used his superior climbing ability to outwit the defending champion, who suffered on the Galibier in the freezing rain, allowing Pantani to go on and win the 1998 title.

In 2011, marking 100 years since the first appearance of the Alps at the Tour, the race climbed the Galibier from both sides on consecutive stages. The tunnel was reopened in 2002, and the 2011 route took the riders over the high road on stage 18, while the tunnel was employed for stage 19. Luxembourg’s Andy Schleck (above) was the first to the summit on both occasions – winning stage 18 when it was the final climb, while on stage 19 it appeared en route to the finish at Alpe d’Huez, won by Frenchman Pierre Rolland.

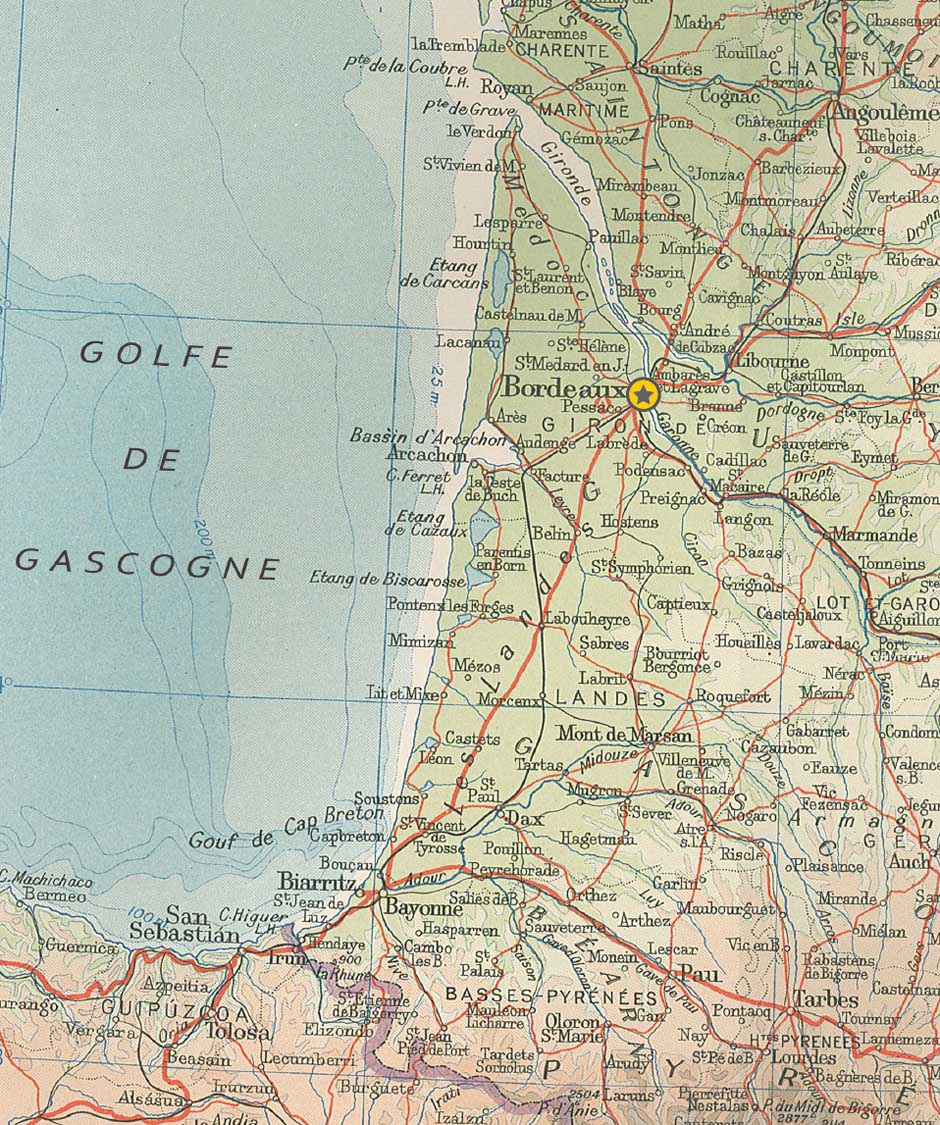

Bordeaux, France

‘It was first used as a stage finish and start in the first Tour de France in 1903, and has been used eighty times between then and 2010’

After Paris, the French west coast city of Bordeaux is the Tour’s most-used destination – for stage starts or finishes – most often acting as the finish for a massed sprint. It was first used as a stage finish and start in the first Tour de France in 1903, and was used eighty times between then and 2010.

English speakers have had great success in Bordeaux over the years: American Davis Phinney won the second of his two Tour stage wins there in 1987, from Dutch sprint star Jean-Paul Van Poppel and Great Britain’s Malcolm Elliott, while Brits Barry Hoban and Mark Cavendish have also won there.

Hoban (above) won in Bordeaux on stage 18 of the 1969 Tour, and then won again the following day between Bordeaux and Brive-la-Gaillarde, becoming the first British rider to win two consecutive stages, and remaining the only British rider to do so before Mark Cavendish came along.

Cavendish won his own Bordeaux stage in 2010, which is the last time the Tour has finished in the city.

The Bordeaux stages used to finish at the outdoor Lescure velodrome, which later became the home of the Girondins de Bordeaux football club, and is now called the Stade Chaban-Delmas after former city mayor Jacques Chaban-Delmas.

The city’s indoor Vélodrome du Lac was cleverly used by British rider Chris Boardman to break the Hour Record, on the same day as stage 18 of the 1993 Tour de France between Orthez and Bordeaux (won by Uzbekistan’s ‘Tashkent Terror’ Djamolidine Abdoujaparov from the USA’s Frankie Andreu). The publicity helped secure Boardman a pro contract later in the year with the French Gan team.

The following April, the velodrome was used by Scotland’s Graeme Obree to break Boardman’s record, then used again in September, October and November 1994 by Miguel Indurain, Tony Rominger and Rominger again, respectively, each rider breaking the previous record.

Today, the velodrome hosts a round of the UCI Track World Cup, while the city of Bordeaux will continue as a popular stage town for the Tour.

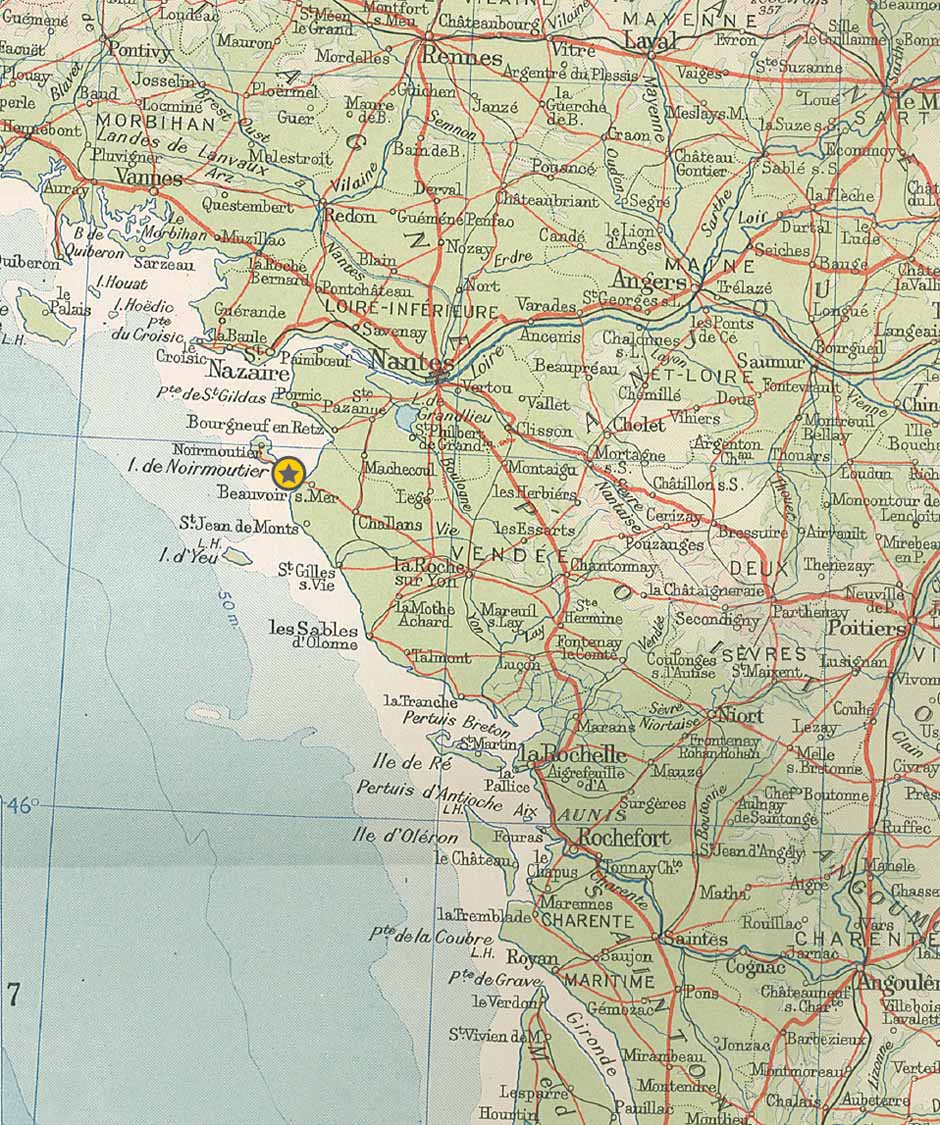

Île de Noirmoutier/Passage du Gois, France

‘It created chaos as a huge pile-up affected a number of race favourites’

The Île de Noirmoutier is an island that sits just off the Vendée coast of western France. It’s joined to the mainland by both a road bridge and the Passage du Gois – a 4.15-km (2.58-mile)-long road submerged by the tide twice a day.

There’s an annual running race across the Passage du Gois, at which the starting gun is fired when the tide first covers the road, with the slower runners getting very wet feet indeed. The Tour has used it only twice – with very different results.

The 1999 Tour started at the nearby Puy du Fou theme park. Stage 2, two days later, was between Challans and St-Nazaire, and featured the Passage du Gois (below) along the way. It created chaos as a huge pile-up affected a number of race favourites, including Switzerland’s Alex Zülle, Italy’s Ivan Gotti and France’s Christophe Rinero, who was considered one of the favourites by virtue of his fourth place overall and the king of the mountains title he won at the doping-scandal-hit 1998 Tour.

All three limped home more than six minutes behind the lead group, which had included Richard Virenque, Fernando Escartin and eventual overall winner Lance Armstrong, although Zülle battled gamely for the rest of the race to finish second in Paris to Armstrong by just 7 minutes 37 seconds.

The ‘homonymic pair’ of Marc Wauters and Jonathan Vaughters, as American cycling writer Samuel Abt described them at the time in The New York Times, were both forced to abandon the race entirely due to their injuries, with American Vaughters taken to hospital having sustained a fractured chin.

The Noirmoutier bridge was used for the stage-1 time trial of the 2005 Tour – the organisers seemingly happy to avoid the slippery stones of the Passage du Gois that year. Young American rider David Zabriskie recorded the the Tour’s fastest ever individual time-trial stage – 54.676 kph (33.974 mph) – over the 19-km (11.8-mile) course between Fromentine, on the mainland, and Noirmoutier. However, following the 2012 USADA investigation into Armstrong and Zabriskie’s former team, US Postal, Zabriskie’s admission to having doped during part of his career resulted in a six-month ban and the annulment of his results between May 2003 and July 2006.

The Passage du Gois reappeared in 2011, although this time the Tour got under way with a ‘neutralised start’ – i.e. a procession – onto the ‘passage’ from Noirmoutier, and the race was only officially waved on its way once the riders had safely ridden to the end of the road where it joined the mainland.

The bridge will undoubtedly be used again in the future, but it remains to be seen whether the Tour will ever race across the Passage du Gois in anger again.

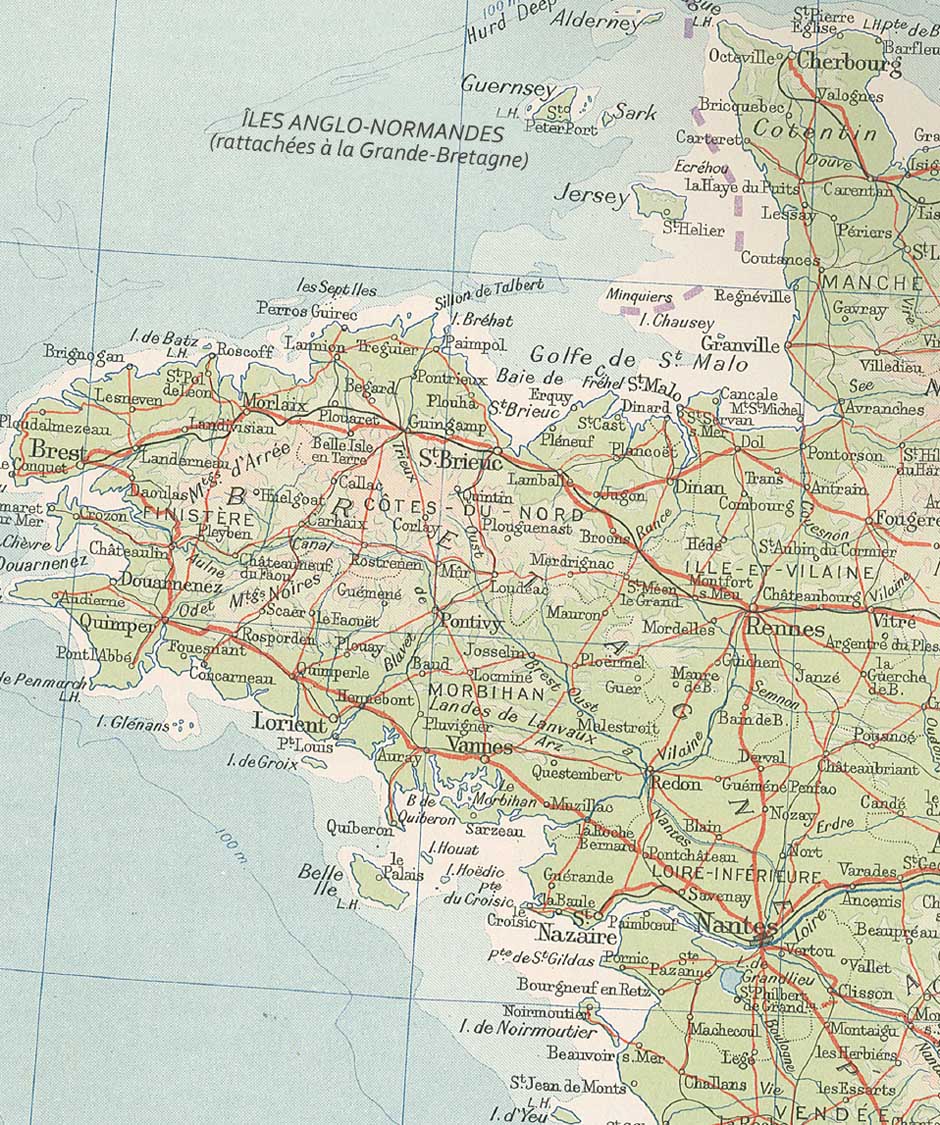

Brittany, France

‘Both three-time Tour winner Louison Bobet and five-time champion Bernard Hinault come from the windswept region, and grew up spending hours battling the often harsh Breton winters on their bikes, moulding themselves into the tenacious riders they became’

Like Normandy, Brittany is a regularly visited region by the Tour and, although it might lack the guaranteed excitement of the climbs of the Pyrenees or the Alps, these flatter regions have nevertheless between them been the scene of a number of significant escapades.

Rennes had become the first Breton town to host a stage of the Tour in 1905, and the race has returned to Brittany almost every year since.

In 2008, Brest hosted the Tour’s Grand Départ with an opening stage run as a massed-start road race – the first time that the Tour had started without a time trial since 1966 (the opening stages in 1971 and 1988 were held as team time trials). Spain’s Alejandro Valverde – who was racing under the cloud of having been named in the 2006 investigation into infamous doctor Eufemiano Fuentes and his high-profile sporting clients, and would in 2009 receive a two-year ban for blood doping – jumped clear of his rivals on the uphill finish in Plumelec to take the race’s first yellow jersey.

Just three years later, in 2011, when it was the neighbouring Vendée’s turn to host the Grand Départ, it was followed by no fewer than four stages in Brittany, showcasing the region through sprint wins by Tyler Farrar and Mark Cavendish in Redon and at Cap Fréhel, respectively, while eventual overall winner Cadel Evans showed what was yet to come by outsprinting Alberto Contador at the finish at Mûr-de-Bretagne.

Is it a coincidence that two of the greatest Tour riders of all time hail from Brittany? Probably not. Both three-time Tour winner Louison Bobet and five-time champion Bernard Hinault come from the windswept region, and grew up spending hours battling the often harsh Breton winters on their bikes, moulding themselves into the tenacious riders they became.

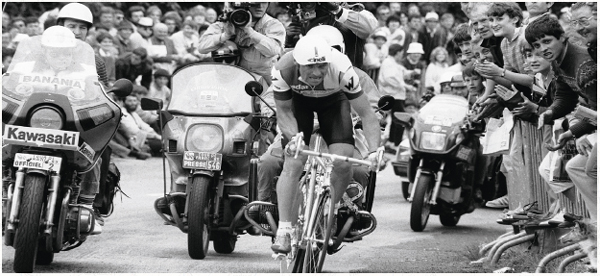

In 1985, the Tour started in Plumelec, where, appropriately enough, Hinault (below) won the prologue time trial. Despite pressure from Ireland’s Stephen Roche and his own team-mate, Greg LeMond, along the way ‘The Badger’ recorded his fifth and final Tour victory in Paris that year. Although it may be hard to believe, that 1985 win remains the last by a French rider, and so the home nation could do a lot worse than to look to Brittany to again produce its next great cycling champion.

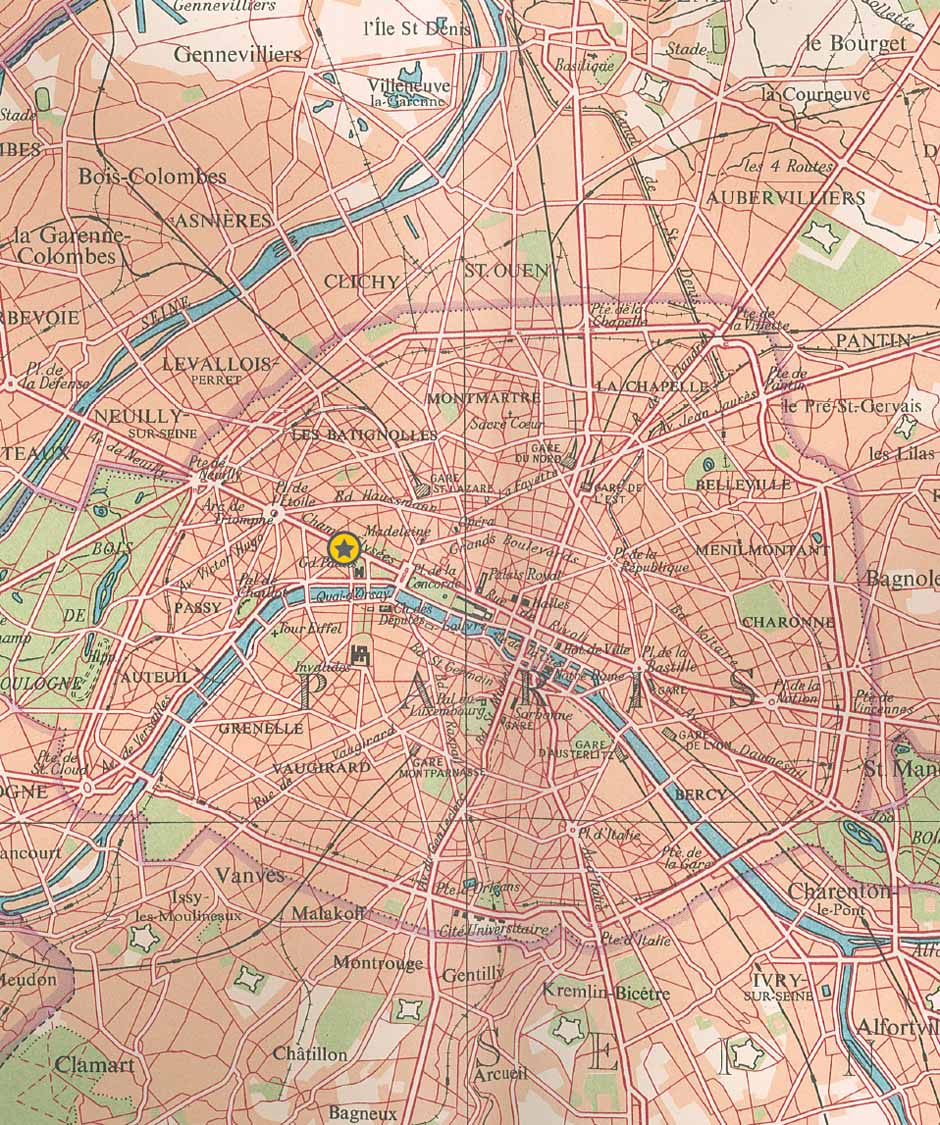

Champs-Élysées, France

‘It becomes a show for the sprinters, and the speed ramps up and up as all the riders realise that the finish line is in sight after three tough weeks’

Belgian Walter Godefroot was the stage winner on the Champs-Élysées when Paris’s famous boulevard was first used as the finish of the Tour in 1975, having previously finished in the Parc de Princes velodrome since the race’s inception in 1903 until 1967. For the next seven years, it finished at another Paris velodrome, the ‘Cipale’, in the Bois de Vincennes.

Traditionally, the Tour’s final stage has nearly always been one of fun and high jinks, with the overall result having already been decided on the previous day. The 1979 edition provided an exception, though, when second-placed Joop Zoetemelk attacked race leader Bernard Hinault, despite being more than three minutes in arrears on the general classification. Hinault had no choice but to react, and proceeded to win the stage and teach the Dutchman a lesson.

Even on more sedate final stages, once the race actually hits the Place de la Concorde just ahead of the Champs-Élysées, all hell tends to break loose as the riders jockey for position and put on a show.

It becomes a show for the sprinters, and the speed ramps up and up as all the riders realise that the finish line is in sight after three tough weeks.

Uzbekistan’s DjamolidineAbdoujaparov never really had the line in sight when he put his head down and failed to see the feet of a Coca-Cola crash barrier at the side of the road during the final stage of the 1991 Tour. The beefy sprinter hit the ground hard, but was helped – bleeding and confused – across the finish line by doctors and officials in order to sew up that year’s green jersey competition, before going for some stitches of his own.

The Champs-Élysées stage is called ‘the sprinters’ world championships’ due to the attention focused on it each year, and official 2011 world champion Mark Cavendish won on the famous boulevard an astonishing four times in a row from 2009 to 2012, and was thwarted from taking a fifth in 2013, finishing third to stage winner Marcel Kittel and Andre Greipel

It hasn’t all been sprints, however: in recent times, both Eddy Seigneur (1994) and Alexandre Vinokourov (2005) have eluded the sprinters’ teams to take solo stage victories. In 1989, the Tour created the most suspenseful finish to the race of them all when the final stage was run as an individual time trial. The USA’s Greg LeMond trailed French favourite Laurent Fignon (below) by 50 seconds, which seemed an impossible gap to close over the 24-km course from Versailles. But close it the American did, tacking on an extra 8 seconds to win the Tour by what remains the smallest ever margin.

In 2013, the Tour had a twilight finish on the avenue — a spectacular finish that also saw the race circle the Arc de Triomphe for the first time, which it’s set to do again in 2014.