Navy sailors and Marines teamed up to defeat Mediterranean threats as far back as the 1790s; they partnered to conquer the Confederate Army in New Orleans in the 1860s; and they fought side-by-side in World Wars I and II. The Marines have needed the Navy to get to the fight first, and the Navy has needed the Marines to extend its reach on to shores. It’s not like Jack Nicholson’s character berating Tom Cruise’s character in A Few Good Men. Marines and Navy sailors can and do play nice together. Sometimes it takes personal experience to understand that. As a Navy man, my first tour at sea gave me a newfound respect for the Marines when I found myself leading a squad of sailors into harm’s way.

On August 22, 2003, the 1st Expeditionary Strike Group set sail from San Diego en route to the Persian Gulf to fight the global war on terror in support of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. The strike group consisted of 3 amphibious assault ships, a cruiser, a destroyer, a frigate, a submarine, 2,200 Marines, and 3,000 sailors. We sailors navigated the ocean, and the Marines hit the weight room; we shared chow lines, shower facilities, and Internet services. Conceptually the group represented an innovation in maritime strategy: Every element of the Navy’s power was being brought into one cohesive, deployable force, giving the president a spectrum of assets ready to respond to any regional threat.

Over the course of six months of operations in the Persian Gulf, we flexed our capabilities. We conducted amphibious operations putting more than a thousand troops to shore, provided point defense for offshore oil platforms, and patrolled the region looking for smugglers. One of my duties on board USS Germantown was as the assistant boarding officer for the visit, board, search, and seizure (VBSS) team. Our team had almost contradictory missions. One was to aggressively patrol, identify, and interdict smugglers violating UN embargoes on Iraq, the other was to provide humanitarian relief in the form of food and supplies to vessels that had been detained for violations. This philosophical dichotomy required us to have a unique preparedness and mindset. On one hand, my team was fierce and ready to extinguish any threat to the ship; on the other hand, we had to provide humanitarian resources because some of the ships we searched were honest brokers obstructed by U.S. forces by circumstance. My team had to be ready to kill or protect within a split second of shifting events.

The first time I led one of these missions, I felt as close to the fight as any of my Marine classmates. We were patrolling the central Gulf when we were tasked to board a six-hundred-foot freighter en route to Iraq that was suspected of smuggling. While Germantown changed course and sped to intercept the ship, my team began our preparations.

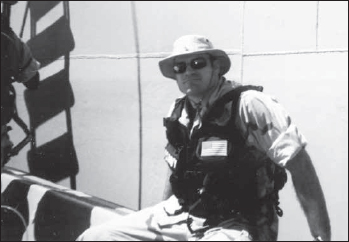

We changed into desert fatigues, strapped on utility vests and gloves, and headed down to the armory to get weapons. Officers carried 9 mm handguns, but the rest of the team had M16 rifles or shotguns. Our gear was unique because we had to have flotation capability but also enough tactical space for extra ammunition, a flashlight, a medical kit, and a camelback for water. It was my responsibility to make sure we were equipped, prepared, and safe. We rendezvoused on the boat deck for muster. I quickly surveyed the men to make sure everyone was present. I asked them to check their weapons and make sure they could remain hydrated since the mission could last up to ten hours. I ordered everyone into a weapons posture—round chambered, clip inserted, and safety on—that would give us the most readiness with a needed level of security.

With the whole team accounted for, we tested our communications with one another and with our bridge crew. We quickly reviewed what we knew of the vessel: name, next port of call, last port of call, number of occupants, basic layout, cargo, and any other details available. This information was important and documented by our officers. If anything was found to be inconsistent once we were on board, we would know the ship’s crew was lying. Finally, we reviewed our tactics and reminded each other of our roles. We hadn’t had a lot of training for this before our departure, so quick huddles were essential for maintaining unit cohesiveness once we boarded the suspect ship. Confusion can increase on board another ship because there is no familiar frame of reference. We quickly reviewed our plan. Two security teams of three men each would sweep the vessel and secure the crew. The boarding officer and I, with a petty officer for extra security, would proceed to the pilothouse to interview the master, while a fourth team with an engineer would inspect spaces and holds and take soundings in tanks.

Once we were clear on our assignments, we were ready to disembark USS Germantown and proceed to the vessel we were intercepting. The eleven-meter rubber-hulled inflatable boat, “rhib” for short, was lowered into the water, and my team climbed down two stories on a rope ladder to board the boat. Once on board, we made our approach to the suspect vessel at high speed. With nothing to do but wait as the rhib traversed the gap between Germantown and the suspect vessel, my mind contemplated the potential hazards we might encounter. I felt anxiety like never before.

Questions flooded my mind. What if they opposed the boarding? What if they were trafficking in illicit cargo? Was I prepared for the mission? Would I be able to do my duty? While these thoughts were going through my head I knew I could never let the men see my uncertainty or fear. Many of them were even younger than I was and probably feeling similar anxieties. I had spent years at the Naval Academy learning the importance of confident leadership, so even though I felt plenty of fear, I tried to project the image of a stoic leader as the rhib bounced through the swells toward our target.

The Navy’s protocol for approaching another vessel respects the United Nations’ Law of the Sea. The United States does not have the right to obstruct foreign vessels on the high seas without reason, but within the northern Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman, we had authority to search. The suspect vessel was expecting us because Germantown’s bridge crew had already established contact with them by radio and had directed them to a safe course and speed in anticipation of our boarding.

Once alongside the merchant vessel, we began to make our ascent on board. By this time, it was easier to put my fears aside and focus on the mission. I would quickly discover that just getting on board the other ship was often the scariest aspect of a mission. While Germantown, with its deep draft, sturdy ladders, and expert seamanship, made boarding the rhib easy, the rickety rope ladder of the suspect vessel was far less steady. Waves swelled treacherously and tossed us about as we tried to grab the rungs of the ladder. My team finally made it on board and hurried to carry out our assignments.

As soon as my feet hit the deck, I began to survey my surroundings. My eyes were immediately drawn to the bow and dozens of gas masks strewn about on the deck. In my anxiety, my overly imaginative mind went to a worst-case scenario, and I wondered if the ship might be carrying weaponized gases. Prepared for anything, our security teams began their sweeps down the port and starboard sides of the ship as the boarding officer and I made our way to the pilothouse. We moved tactically and quickly, aware that danger might lie around any corner of the unfamiliar ship. We also had to trust our teammates, as they proceeded to secure the rest of the ship.

When we arrived at the pilothouse, the boarding officer began interviewing the ship’s master, and I took reports from the rest of the team. Because I was at the highest point of the ship, I could maintain better command and control. Both teams reported all secure, and the whole crew was accounted for. Our engineer began taking soundings in their fuel tanks as the interview with the master proceeded. Fuel tanks could hold illegal substances, and it was a place weapons could be hidden.

The pilot master spoke English, which was pretty common, and he confirmed their cargo and destination. When asked about the gas masks, he offered a very plausible explanation—they were used for hazardous materials handling. The engineer’s inspection took about thirty minutes, and as it progressed Germantown steamed on a parallel course to provide cover for us and the rhib; we frequently radioed them on the bridge-to-bridge radio to update them on our status and progress. Finally the engineer reported that he had completed his soundings and hadn’t discovered anything unusual. We thanked the master for his compliance and headed back to the ship.

Such search missions were only half of our duties. Other times we clearly offered charity, which required an entirely different leadership mindset. Quarantined in a ten-by-ten-mile grid of ocean, affectionately known as the “smug box” (as in smuggler), some ships sat at anchor for months at a time while authorities ashore made determinations as to their status. While the ships’ owners and masters might have been smuggling illicit cargo, their crews were impoverished victims. They were often third world citizens that had signed on with a ship to make a meager wage to support their families.

We still approached charitable boarding with the same preparation as for uncooperative vessels—weapons ready. One time as we approached the coordinates of a vessel for which we were providing provisions, I was struck by the putrid odor in the air. As the vessel became visible through the polluted haze of the northern Persian Gulf, the odor became stronger. I realized with shock that it was emanating from the ship we were about to board. Sanitation standards are not the same in the Middle East as in the United States. We had to follow strict environmental laws as part of our seagoing practices, but it was not uncommon for some foreign vessels to dump sewage and food waste, or slaughter a calf on the deck of a boat, leaving its remains to float in the gulf’s waters.

Coming alongside the vessel, we had our first glimpse of its dire circumstance, as the ship wallowed in spilled oil and human waste in the stagnant water. Braving the noxious odors, we boarded the vessel with flour, fresh water, and some other meager supplies. An appreciative crew of six men greeted us. They were a sad sight, completely emaciated and wearing torn and stained clothing. They obviously had not bathed in months, choosing instead to drink the precious little water that was provided to them. As was our practice, we inspected the vessel to ensure their safety and ours.

Once we were certain there were no weapons or other hazards on board, we proceeded with distributing supplies. We conducted health and wellness checks on the crew members if they wished. They lined up, and our corpsman listened for symptoms they might have, while also visually assessing if they needed treatment. As the doc attended to the crew, and members of my team unloaded the supplies, a gunner’s mate who was providing my security briefly surveyed the ship. Our visit was during the holy month of Ramadan, and we had boarded in the late afternoon, so we saw the cook preparing their evening meal to break their fast. With the flour and water we had provided, the cook made unleavened bread in a fly-infested kitchen. It was nothing short of filthy, and the food was meager.

I had never seen poverty of that kind before. I realized that these men were guilty of nothing, just hoping to make fifty cents a day to send to their families. Theirs was a simple case of bad luck—signing up to serve on a vessel whose proprietor was smuggling oil. It occurred to me at that moment that what separated my relative wealth from their poverty was not any ability or work ethic, but our circumstances of birth. I had the good fortune to have been born in the United States. I didn’t fully appreciate it at the time, but I have since come to regard those charitable missions, providing food and comfort to the world’s underprivileged, as one of the most rewarding aspects of my naval service. Further, that our nation and naval service continued to focus energy and resources on benevolent charitable missions—and that I had the opportunity to serve in this capacity—imbued me with a sense of purpose and pride.

While leading fellow sailors under arms into potentially dangerous situations on VBSS missions, I had to call upon my Naval Academy training to overcome the unique leadership challenges, anxieties, and uncertainties that came with the diverse missions we were assigned. Inspections of suspect vessels forced us to focus on preparedness and judgment, while the charitable aspects of the mission imbued us with empathy and led to a newfound appreciation for the blessings we enjoyed because of the missions our Marines were performing. This perspective furthered the partnerships of the sailors and Marines of the 1st Expeditionary Strike Group and led to mutual respect between the Marines embarked on board ship and the VBSS sailors of Germantown.