The dirt roads leading out of the city of Voinjama were some of the worst in all of Liberia. It took almost an hour for our UN patrol vehicle to travel the short distance from the city to the village of Masabulahun. Thankfully it was January and the beginning of the dry season, otherwise the roads would have been impassable trails of red mud. Occasionally we passed a pickup truck overflowing with people and supplies headed toward Sierra Leone or Guinea, but otherwise the roads were clear, and it was a lonely journey. I had plenty of time to reflect on how I had gotten there and what a unique deployment I was entering.

As a submarine officer, I never imagined my career path would bring me to the jungles of West Africa. A Navy officer’s career progression is generally rigid and does not allow for opportunities outside the submarine community, so when I was offered the opportunity to serve with the UN mission in Liberia I jumped at the chance. At the time, I didn’t even realize that the United States sent officers to UN missions.

Many of the countries that support UN missions do not have large militaries, therefore sending fifty or one hundred soldiers to a UN peacekeeping mission is significant, and only the best and brightest are chosen. Presently there are twenty deployed U.S. military members supporting several UN missions. This is a small number and will remain small because the United States provides so much financial assistance to the United Nations. In our compound, I was the most junior officer and the youngest, but I was the team’s operations officer, a senior position, because I am an American, and Americans are considered to be particularly capable and hard working. It was an honor for me.

That first trip from Voinjama had left me tired and thirsty from inhaling dust and dirt kicked up by our vehicle. I was also nervous. I had only been working in Liberia as a UN peacekeeper a few days prior to heading out on my first patrol. I barely knew my teammate, a friendly Nigerian named Nehemiah, and now we would be on a patrol together to an isolated village in the Liberian countryside for the rest of the day. Our task was to enter a village of complete strangers and assess health conditions, education, economic development, and crime in the community. The first village we visited was one of nearly one thousand towns and villages under our jurisdiction. We were unarmed peacekeepers, each wearing our national military uniform and a light blue and white armband to signify our mandate. I didn’t really know what I was supposed to be doing or how the villagers would react to our presence. Arriving at the town, I grabbed my camera and clipboard and got out of the patrol vehicle.

As soon as we entered the village of Masabulahun, we were greeted by young, cheering Liberians. I had pens, pencils, and candy for them. The flag on my uniform instantly put people at ease and let them know that I was there to help. The children truly enjoyed seeing a tubabu (white man) and wanted to pose for pictures. When the excitement died down, several women and children took us to see the town chief. He was the only man in the village at the time since all the others were out working the fields.

We sat down in a palava hut, the town meeting place, and started discussing conditions in the village. We covered some heavy issues, including security, education, human rights, and the treatment of women and ex-combatants. The town chief asked for more resources. It was a town with no running water or electricity, but he wanted computers. It was a town miles away from an economic hub, but he wanted machinery to process grain and corn. Even though I felt they were ridiculous requests, I wrote them all down as “needs” in my notebook. I didn’t know what else to do. Then my Nigerian teammate sat down and began asking questions. He asked when the town had last pooled its resources to earn extra income for a processor. Did they hold a meeting with the young men about their work ethic and their contribution to the town’s food supply? Why hadn’t they developed a program for the girls to help in the fields?

My teammate was African, and he was trying to impart a sense of responsibility to the villagers. It was an awkward feeling for me. I felt bad for the locals. Their huts were made of clay, the children had mismatched shoes, and their food was served out of unsanitary pots. One potential drawback of international peace operations is that the host nation can become dependent on the United Nations and non-governmental organizations for food, security, and a myriad of other services. Instead of perpetuating this dependency, it is better to teach the villagers the skills to sustain UN and NGO efforts long after these organizations leave. It is a painful but necessary lesson for them to learn.

Not every village was the same. Some made the best of the United Nations and NGOs operating in their country. They took pride in their villages and were excited to show the progress they had made. Whether it was a clean-water initiative or some other community health measure, survival was only possible with hard work and collaboration among the tribal leaders—often a town chief, a women’s leader, and a youth leader. When there was a rule of law dispute, the community of elders made a decision and a ruling. It was a defined structure based on norms, not laws.

Although the overwhelming majority of developments in northern Liberia were positive, we did experience a serious problem during my time there. World food prices skyrocketed in the spring of 2008, and the effects of this could be seen in the local markets. Many people in northern Liberia traveled across the border to Guinea and Sierra Leone in search of cheaper food prices. Families dramatically cut back on their food consumption, and there were concerns that many young children would begin to starve. Ultimately, the World Food Program intervened and distributed rice and other goods to help stabilize prices. It was certainly a tense period during my tenure in Voinjama; the worst of the food shortage seemed to be over by the time I left.

My deployment went far beyond patrolling villages in the Liberian countryside. It also gave me the opportunity to live and work with people from all over the world. I lived with a team of international military officers from more than fifteen different countries. I was the only native English speaker, and thus I felt an obligation to help my teammates gain proficiency with the language. I knew I was having an impact when I heard my Ukrainian teammate using slang and curse words he had picked up from me after hours on patrol together. In addition to the time spent with my teammates, I had the opportunity to work with numerous UN agencies, such as the UN Development Programme, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and UN Police, as well as several NGOs, including the International Committee of the Red Cross, International Rescue Committee, and the Right to Play. Collectively, the UN agencies, NGOs, and military units saw tangible results in northern Liberia. Improved roads, new government facilities, and a new hospital are just a few of the projects completed while I lived there.

In addition to living and working with international officers and NGO workers, I also spent a great deal of time with a Pakistani infantry battalion (Pak Bat) providing security throughout my area of responsibility. As military observers we were unarmed to provide governance and structure, but the Pak Bat provided the consistent physical security in the region. The Pakistanis also provided our team with food, clean drinking water, and fuel.

Pak Bat was a gracious host and helped make my stay in Liberia enjoyable. The Pakistani commander frequently hosted formal lunches and dinners for our team; his contingent served the most delicious chicken, rice, chapati (a type of pita bread), paneer, and sanagalu (chickpeas) I’ve ever had. I developed a good working rapport with the Pakistani soldiers and was constantly impressed by their knowledge of U.S. current events. The presidential primary campaigns of 2008 were in full swing while I was in Liberia, and the Pakistani officers were familiar with all the main issues. Each day I joined them for lunch, they wanted me to explain something about how the American system of government works and how we elect the president. I was impressed by their knowledge of our government and their desire to learn more about our democracy. It certainly made me feel good knowing that other countries were impressed and respectful of our government even at a time when many Americans seemed frustrated by it. Some headlines indicated that the Pakistani military could not be trusted and claimed that there was evidence that the Inter-Services Intelligence directorate was collaborating with the Taliban. To me, however, these men were my only protection, and we became great friends.

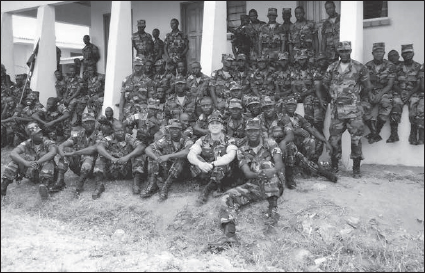

Dave Augustin with Liberian partners. (Courtesy Dave Augustin)

I spent a great deal of time working with the Pakistani officers coordinating air and ground patrols and documenting the disposal of unexploded ordnance (UXO). The area saw a great deal of fighting during Liberia’s fifteen-year civil war, and remnants of the hostilities constantly turned up in villages. UXO was the biggest problem in the country; each week my team accompanied the Pakistani explosive ordnance disposal detachment to a new village to destroy weapons. Rocket-propelled and hand grenades accounted for the vast majority of UXOs discovered, but occasionally villagers found buried automatic weapons and ammunition. During the construction of a hospital right next to my team’s residence, a worker unexpectedly detonated a UXO while burning some trash. Fortunately, he was unharmed, but it reinforced that UXOs were all over the country.

I was never more proud to be an American than while serving in Liberia. Seeing the joy on the faces of Liberian children when I entered a town, teaching my teammates English while on long patrols, and discussing politics with the Pakistani wardroom reinforced my belief that the United States is widely respected around the world. At a time when negative media coverage of U.S. operations in Iraq and Afghanistan had many Americans questioning our role in the world community, my experience proved that Americans still had a responsibility to lead.

When it came time for me to leave Voinjama, I felt conflicting emotions. I was excited to go home and see my wife and family, but I knew there was so much more that could be done if I were to stay there longer. When I boarded the Ukrainian Mi-8 helicopter for my last trip back to the capital, Monrovia, I looked out the window at the pristine, unmolested forests that cover the beautiful Liberian countryside and thought about what a unique opportunity I’d been given to represent my country and the United Nations. My time in Liberia left a lasting impression on me, and I will never stop hoping and praying for lasting peace and prosperity for that country and its people.