Some people have no direction, no purpose, and no idea where their lives will take them. Opportunities pass them by. The kids get raised, the mortgage gets paid, and the status stays quo. They’re just along for the ride. Other people have a laser-like focus on where they need to be and a clear, but maybe less precise, idea of how to get there. They set goals and navigate a course undeterred by detours to the finish line. They are the world’s drivers.

I always knew where I needed to be, I just wasn’t sure how to do it. I wanted to be a pilot, like my dad, and I wanted to be a leader; everything else was just chaff. When I read President Theodore Roosevelt’s “Man in the Arena” speech my first week at the Naval Academy, it reinforced my passion to be on the front lines. There I was, even during plebe summer, in the arena, my face marred with “sweat and dust and blood” from bear crawls on Hospital Point. I was doing what it took to achieve my goals, leaving behind the “timid souls” who know neither victory nor defeat.

In my early years, things were pretty much the same for me as they were for other military brats. I come from a Navy family. My dad, both my grandfathers, aunt, and an uncle were naval officers. During my first six years of education, I attended a different school every year. When my family moved to Richmond Hill, Georgia, however, I started the sixth grade and finally had educational stability because we never moved after that. It was there that I began the serious effort of earning an appointment to the Naval Academy. The Annapolis brochures said I should strive for good grades, have lots of extracurricular activities, and try to get leadership experience. Of course, I also needed a requisite dose of luck. In pursuit of the nomination, I received some much-needed character-building lessons.

Much of my interest centered on student government. I served on the student council every year in high school. As a freshman, I was the treasurer, and as a junior I ran for student council president but lost. This was a major blow to a young man focused on attending a college where leadership was a prerequisite. Pursuing school-wide office was uncommon for a junior, but I had the respect of so many different cliques that I gave it a shot, believing I could tally enough votes to win.

While living on different military bases, I never had the luxury of picking and choosing my buddies. I accepted anyone who accepted me. I lost the council president race because a malicious student council adviser, Mrs. Stenson, had shown favoritism toward another candidate. I was disappointed: How could I possibly get into Annapolis if I can’t even land a high school leadership role? I accepted the loss, but I didn’t give up. The next year I ran again and was elected council president. I learned something all successful military officers must learn—perseverance. Outside the Naval Academy leadership center is an Epictetus quote under the statue of Adm. James Stockdale that reads, “Lameness is an impediment to the body but not to the will” It really isn’t important how many times you fail, fall, or get knocked down, or even how hard the blow. To truly win, you have to get back up and move forward.

My parents helped me fulfill my dream of attending the Naval Academy. Throughout my life, my mother has been my biggest cheerleader. She told me I could be anything I wanted to be. She told me I was blessed with brains, looks, and family, that I should use these strengths to help others, and that with the right choices and “checking the right boxes” my dreams would be realized. When things went wrong, she taught me to turn to God and learn from my mistakes.

On Induction Day at the Naval Academy, I felt ready. My dad, Class of 1976, made sure I was prepared to be a plebe. Plebes are like freshmen at other, traditional colleges but without civil rights. They are broken down mentally and then built back up, reshaped as officers in the naval service. Last-minute instructions on how to fold T-shirts, polish boots, and memorize age-old sayings from Reef Points—a timeless bible that explains the Naval Academy and the Navy—were an advantage I had as a “legacy” student.

My dad told me if some sadistic upperclassman asked, “How’s the cow?” I should be ready to respond by saying, “Sir, she walks, she talks, she’s full of chalk, the lacteal fluid extracted from the female of the bovine species is highly prolific to the Nth degree, Sir.” My dad also provided some intangible advice: To put my shipmates first, put 100 percent of my energy into every day, and never compromise my integrity. While other midshipmen were still developing their moral compasses, my self-awareness of right and wrong had already been calibrated.

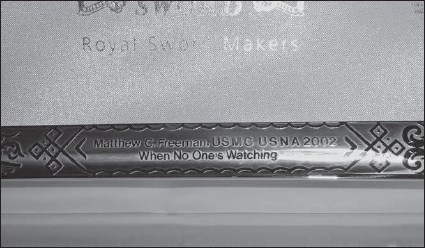

My years at Annapolis were some of my fondest. I did my best as an aerospace engineer and developed close friendships. I wasn’t Brigade commander, but I focused on being a good leader in company and taking care of my squad mates. Flying was in my DNA, but I was going to be different from the other aviators in my family: I was going to be a Marine as well. At graduation, my parents gave me an officer’s sword. Marine Corps officers carry a Mameluke sword, in recognition of the one presented to 1st Lt. Presley O’Bannon by the Ottoman viceroy Prince Hamet during the First Barbary War in 1805. All Marine officers have since had it.

My parents engraved my sword “Matthew C. Freeman, USMC, USNA 2002. When No One’s Watching.” My dad wanted the phrase on the sword to remind me that character is one of the most important and essential parts of being an officer and leader, and the most telling method of measuring character is noting how someone acts and conducts his affairs when no one is watching.

After six months of officer training at the the Marine Corps Basic School at Quantico, Virginia, I went to flight school. Becoming a pilot required twenty-four months of additional education, and with a war going on, I was particularly impatient. Because of the needs of the Corps, I was assigned orders to a C-130 squadron based in Okinawa, Japan. Our mission was to take bullets, boots, and Band-Aids in and out of the area of combat operations, always in a support role.

Though my desire to be more involved in combat operations remained unfulfilled, personal things were on track living overseas. I was blessed to have my childhood friend and now fiancée, Theresa Hess, living with me in Japan. Theresa was an Air Force flight surgeon and had wrangled a job in Okinawa as well. We were able to enjoy the Japanese culture together and nurture our relationship. We took walks on the beach and bought eclectic Japanese delights. Our favorite was Norimake-Zushi, a delicious fresh fish wrapped in seaweed. We explored the island and snorkeled and scuba dived right in front of our apartment. I traveled to Australia and dove off the cliffs there. I played with monkeys in the Philippines and took pictures on Wake Island and Guam. Life was good, but something was missing. I felt disconnected from the history ongoing in Iraq and Afghanistan.

On a typical morning around the squadron hangar, my executive officer called a meeting for all the junior officers. He read an email explaining that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were continuing much longer than expected, and there was a shortage of troops on the ground due to extended Army deployments. There were not enough troops in the active, reserve, and guard components to maintain mission requirements. Positions were opening up for individual volunteers, or volun-“told,” officers to augment Army forces on the ground. It was explained that an Army infantry unit responsible for mentoring the Afghan national army needed more personnel. Assignments to the unit were supposed to be for an entire year in Afghanistan.

Operations were slow in the Pacific region, and I felt the need to be closer to the fight. Aside from leaving Theresa, I was excited about the opportunistic deployment. My executive officer slated me to deploy individually to Afghanistan.

My pre-deployment checklist was in order: buy the right books, pack the sea-bag to the brim, and email friends an address for care package deliveries. I purchased and began reading Ahmed Rashid’s Taliban and Descent into Chaos. I also bought and read the Army and Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual by David Petraeus, John Nagl, and James Amos. The Military Exchange had ample supplies needed to complete my rucksack: 1,000-mile-per-hour cord, lighter, knife, cold weather gear, canteens, harness, and survival gear. I had one other item on my to-do list: marry the love of my life.

Theresa and I secretly married on July 7, 2009, in a civil ceremony in Richmond Hill days before my departure. No one from our families was allowed to attend because we didn’t want to detract from our “real” ceremony, scheduled for May 2010, upon my return. During my pre-deployment R&R (rest and relaxation), my USNA roommates Omar Garcia and Liam Hughes came to spend a few days with my family. We argued about politics, knocked back a few beers at the bar, and went shooting at the local range, having fun but also sharpening my rifle skills for operations downrange.

Arriving in Afghanistan was exhilarating: hundreds of helicopters, cargo planes, and combat aircraft were dancing around the airfield. Getting past Bagram Airfield, the dustiest place on earth, was the first hurdle, before arriving at my forward operating base in Kapisa province. I was working with the Georgia Army National Guard’s 108th BCT, 48th Brigade. It was so ironic. A Georgia boy, stationed in Japan, sent to assist a random unit in Afghanistan. Of course, it had to be from Georgia.

We talked about the Georgia Bulldogs being the best team in the Southeast Conference and about the superior hunting and fishing in Georgia. We channeled that competitive spirit into plans for how the unit was going to better train and mentor the Afghan volunteers. We knew we needed the Afghans to take control of their own country and to be able to work as an organized army to do that. Otherwise, we would never go home.

I forged a bond quickly with the guys of the 108th. They respected my Marine Corps insignia, but I also did everything possible to put the soldiers first. I remember Gen. Charles Krulak telling us as midshipmen, “Officers eat last.” We relearned that philosophy at Quantico, and I embraced that attitude every day.

During my early missions, I fell in love with the scenery and the people of Afghanistan. We would patrol villages, and once it felt secure, the locals would swarm our humvees with smiling faces, little children asking for candy and school supplies. In an email after my third patrol, I wrote my mother, a middle school teacher: “Mom, the kids would rather have pens and paper more than anything, even food or water. Would you please start a collection at your school and send them to me? I want to take the pens and paper to the kids so they can improve their education.”

On August 7, 2009, our team planned to execute Operation Brest. We were supposed to approach a key area within our combat zone and perform “presence operations.” Essentially, our task was to let the Taliban insurgents know that we had the confidence and ability to patrol in this particular area. As an officer adviser to the infantry company, I did not have to go on every mission. I had quickly become close with my team, however, and felt like I was responsible for the younger soldiers. Spc. Christopher “Kit” Lowe, from Easily, Georgia, was a particular favorite. He was young and earnest. He loved weapons and had a wonderful humor about him.

We went out of base camp and up toward an area where we knew there would be danger. Recent intel had reported that some eighty Taliban could be in the vicinity. Not more than ten minutes into our patrol, shots rang out. My team dismounted and cleared an enemy position in a mud house. I climbed atop the roof with Kit behind me and killed a man with an RPG during my ascent. I was visually acquiring layout of the area to call in air support when I was hit. Everything went black.

EXCERPT FROM MATT FREEMAN’S POSTHUMOUSLY AWARDED BRONZE STAR CITATION

Acting to conduct a reconnaissance of force in the valley, Captain Freeman’s element received enemy fire almost immediately upon leaving the combat outpost. Pinned down as a result of this fire, Captain Freeman decided to clear a kulat in order to gain access to the top deck and achieve better observation of the enemy’s firing position. Receiving a heavy volume of enemy fire, Captain Freeman led the way in clearing the house and was the first to reach the rooftop. Once on the rooftop, he spotted an enemy Rocket-Propelled Grenade gunman and immediately killed him. He and one of his team members spotted several other insurgents and began to engage while under fire. It was at this time that Captain Freeman fell mortally wounded. He fought with bravery and determination while demonstrating unwavering courage in the face of the enemy.

When his parents heard accounts of Matt’s final minutes, they appreciated knowing the facts of that day. The soldier who retrieved his body after the battle said, “He was found with his finger on the trigger, his magazine almost empty, and he was facing the enemy. A proud death for a Marine.” Everyone else made it home that day.

Matt had a warrior’s homecoming. His brother-in-law, Mike Macias, a veteran of five ground tours in the Middle East, made a pact that if either of them needed an escort home, the other would do it. Matt’s body arrived at the airport in Savannah, and for the entire seventeen miles home to Richmond Hill, people lined the roads in tribute. The police and the Patriot Guard provided an outstanding escort home. There was a five-hour wait for mourners to pay their respects at the funeral. It was as if the entire community of Richmond Hill had lost a son.

Two weeks later, at the chapel in Annapolis, there was another ceremony led by Lt. Gen. John Allen, USMC, who had been a classmate of Matt’s father. Hundreds were in attendance, including family and friends and members of the Classes of 1976 and 2002 and the Naval Academy community. Specialist Lowe, still suffering from wounds and in a wheelchair, was also in the audience. After the ceremony in the chapel, we walked to the columbarium on Hospital Point, led by the 8th and I Marine Corps band. Matt was laid to rest on August 26, 2009.

Matt’s last conversation with his mother had been about the school supplies for the Afghan children. Six months later, his family founded the Freeman Project (www.freemanproject.org), a non-profit whose mission is to procure, ship, and distribute school supplies to children in Afghanistan. Matt was hoping the pens and pencils would replace guns and grenades in these impoverished regions. To date, U.S. soldiers and Marines have distributed more than three tons of school supplies.

*Written in Matthew’s voice by Lisa Freeman, in honor of her son.