The water corridor between New York and Montreal via Lake Champlain and the Hudson and Richelieu rivers was long the scene of conflict between those determined to control half a continent. During the French and Indian War, French colonists on the St. Lawrence and their British counterparts along the Hudson fought up and down it. In the opening days of the American Revolution, Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold led colonial troops—including young officers James Wilkinson and Aaron Burr—from the Lake Champlain country to the very gates of Quebec. Two years later, in 1777, British general “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne marched south from Canada along the lake route, determined to reach New York City and sever the New England limbs of the Thirteen Colonies. That Burgoyne ended up surrendering his army at Saratoga seems not to have been lost upon the British as they began a similar thrust south during the summer of 1814.

The man charged with the exercise was General Sir George Prevost, since 1811 governor-general of Canada and commander in chief of His Majesty’s forces in Canada, the Atlantic Colonies, and Bermuda. During the first two years of war, Prevost’s task had been to hold Canada together administratively and defend it territorially, all the while juggling the incessant pleas of various theater commanders for ever more troops and matériel—both of which were always in short supply. That Prevost was largely successful in this is evidenced by the fact that save for American dominance on Lake Erie, the Canadian–American boundary was essentially the same as it had been in June 1812. Now with the British lion’s patience run out and an abundance of veterans available from the Napoleonic campaigns, Prevost was finally to have both the troops and the supplies he needed to conduct offensive operations.

On June 3, 1814, the Earl of Bathurst, secretary of state for war and the colonies, and as such the principal civilian architect of British policy in North America, sent General Prevost his marching orders for the summer. Embarking from Bordeaux, France, bound for Canada were “twelve of the most effective Regiments of the Army [that had served] under the Duke of Wellington together with three Companies of Artillery on the same service.” When joined by other units en route from Europe, this force would approach ten thousand veteran infantry—by far the largest and most battle-tested British force ever to assemble in North America. With this force under Prevost’s command, Bathurst clearly expected great things.

“His Majesty’s Government conceive that the Canadas will not only be protected for the time against any attack which the Enemy may have the means of making,” instructed Bathurst, “but it will enable you to commence offensive operations on the Enemy’s Frontier before the close of this campaign.” Protecting Canada meant, Bathurst went on to say, finally destroying the pesky American base at Sackets Harbor and regaining naval superiority on Lake Erie and Lake Champlain. Contemplated offensive operations included the recapture of Detroit and the Michigan country, the “retention of Fort Niagara and so much of the adjacent Territory as may be deemed necessary,” and, if possible, the establishment of “any advance position on that part of our frontier which extends towards Lake Champlain.”

Showing that he for one remembered the embarrassment of Saratoga, Bathurst added that Prevost should take care in executing the latter so as not to “expose His Majesty’s Forces to being cut off by too extended a line of advance.”1

If Bathurst contemplated an eventual march to New York City and the severing of New England—the same grand strategy that had failed a generation before—there was no hint of such on the face of his June 3 orders. Perhaps he recognized that the first step was to get Prevost moving in the right direction. Prevost acknowledged Bathurst’s orders on July 12 and wrote that they would be obeyed as soon as his full force had assembled, but that “defensive measures only will be practicable, until the complete command of Lakes Ontario and Champlain shall be obtained, which cannot be expected, before September.”2

That was hardly the response the Earl of Bathurst had expected, considering that the might of the British Empire was now sailing up the St. Lawrence. “If you shall allow the present campaign to close without having undertaken offensive measures,” Bathurst replied icily, “you will very seriously disappoint the expectations of the Prince Regent and the country.”3

Doubtless Prevost had already surmised as much as he assembled his army south of Montreal. Despite Bathurst’s promise of provisions for ten thousand men for six months, Prevost now had more than twenty-nine thousand troops spread throughout Canada. To feed them, he found assistance from an unlikely source. “Two-thirds of the army,” Sir George reported to Bathurst on August 27, “are supplied with beef by American contractors, principally of Vermont and New York.”

It was true. Yankee farmers were putting British gold ahead of American patriotism and sending New England beef and produce flowing north to Canada. Among those on the American side enraged by this was Major General George Izard, who received a letter from one Vermonter bemoaning that “droves of cattle are continually passing from the northern parts of this state into Canada for the British.”

Izard forwarded the letter to the War Department and added his own commentary: “This confirms a fact not only disgraceful to our countrymen but seriously detrimental to the public interest. From the St. Lawrence to the ocean an open disregard prevails for the laws prohibiting intercourse with the enemy…. On the eastern side of Lake Champlain the high roads are insufficient for the cattle pouring into Canada. Like herds of buffaloes they press through the forests, making paths for themselves. Were it not for these supplies, the British forces in Canada would soon be suffering from famine.” Small wonder that Prevost acknowledged that “Vermont has shown a disinclination to the war, and as it is sending in specie and provisions, I will confine offensive operations to the west [New York] side of Lake Champlain.”4

As Sir George’s massive army prepared to do just that, the bulk of the American troops opposing him—some four thousand regulars under General Izard’s command—marched off for Sackets Harbor under belated orders from the War Department that presumed Prevost would strike there first. To no avail, Izard objected strenuously. Brigadier General Alexander Macomb was left to defend the western shores of Lake Champlain with a mismatched assemblage of three thousand regulars and militia, only half of whom were fit for duty. As he left for Sackets Harbor, Izard warned that all of New York north of recently erected works on the Saranac River at Plattsburgh would be in the possession of the enemy “in less than three days after my departure.”5

Actually, it took Prevost a few days more than that. Crossing the border on August 31, 1814, Prevost reached Chazy, twenty-five miles north of Plattsburgh, on September 4. General Macomb’s men felled trees, broke bridges, and engaged in skirmishing to try to stem the British advance, but these tactics did little to slow the onslaught of Wellington’s veterans. “They never deployed [spread out] in their whole march,” Macomb reported, “always pressing on in column.” By the evening of September 6, the British were in Plattsburgh, and Macomb retreated south across the Saranac River to fortifications that overlooked Plattsburgh Bay. Now the British paused and spent four days preparing to assault the American position—tenuously held though it was—while Prevost looked out across the waters of Lake Champlain for some assistance from the Royal Navy.6

The balance of naval power on Lake Champlain had rested with the United States until June 1813 when the overzealous Lieutenant Sidney Smith caused the sloops Growler and Eagle to be lost to the British. This left the Americans to retreat to the upper end of the lake and frantically set about building new ships. (While Lake Champlain runs north and south, it drains north to the St. Lawrence; thus, the southern area is in fact the upper lake.) The British did the same, but unlike Chauncey and Yeo, who had engaged in a shipbuilding race on Lake Ontario, the officers at Lake Champlain were determined to fight once ships were built.

The American commander on the lake, Master Commandant Thomas Macdonough, was certainly no stranger to its waters. Born in Delaware in 1783, Macdonough joined the navy as a midshipman at sixteen. He saw service in the Mediterranean under Stephen Decatur and participated in the burning of the captured Philadelphia. Tall and slender, he became a staunch, God-fearing Episcopalian. By 1807, he was first lieutenant of the Wasp and enforcing Jefferson’s embargo along the Atlantic coast. Afterward, Macdonough took a lengthy leave to captain a merchantman to Calcutta and back before once more applying for active duty at the outbreak of war. He was initially posted to the Constellation as its first lieutenant. But the frigate he had once served on as a young midshipman proved unfit for sea, and he was quickly given command of a small fleet on Lake Champlain, arriving there early in October 1812.

After Growler and Eagle were lost the following June, Macdonough was forced to play cat-and-mouse with the British squadron commanded by Royal Navy Lieutenant Daniel Pring. Macdonough was definitely the mouse as Pring ranged about the lake and even provided transport for British troops to raid Plattsburgh and Burlington. Macdonough confined his forays to the vicinity of the shipyard at Otter Creek near Vergennes, Vermont. By fall both Pring and Macdonough were focused on shipbuilding.7

The centerpiece of Macdonough’s new fleet was the ship Saratoga, launched at Otter Creek, on April 11, 1814. Her name was no small coincidence and was meant as a proud and defiant reminder of America’s greatest victory to date save Yorktown. Larger than Perry’s Lawrence or Niagara, Saratoga at seven hundred tons was armed with eight long 24-pounders and six 42-pound and twelve 32-pound carronades, capable of throwing a 414-pound broadside. Manned by a crew of 210, she was not exactly “Old Ironsides,” but a formidable force on Lake Champlain nonetheless.

To accompany Saratoga, Macdonough could rely on the hastily completed brig Eagle under the command of Captain Robert Henley. Comparable in size to the Lawrence or Niagara, Eagle was armed with eight long 18-pounders and twelve 32-pound carronades. The schooner Ticonderoga was originally a small steamship—still a novelty, as Fulton’s Clermont had debuted only in 1807—but constant problems with the steam machinery forced her to rely on sails and deprived her of the distinction of being America’s first steam-powered warship. At 350 tons, Ticonderoga carried eight long 12-pounders, four long 18-pounders, and five 32-pound carronades. Finally, among his capital ships Macdonough counted the small sloop Preble, mounting seven long 9-pounders. These four vessels were accompanied by an assortment of ten gunboats, each with one or two long guns. That totaled fourteen vessels throwing 1, 194 pounds of broadside, almost two-thirds of which was from short-range carronades. By May, even as the Eagle was still being completed and despite Pring’s efforts to attack his base at Otter Creek, Macdonough was sailing this flotilla off Plattsburgh and was once again in control of the upper lake.8

Pring had a superweapon of his own under construction, but he was not to command her. Despite his knowledge of the lake, Pring had managed to run afoul of Sir James Yeo, still the Royal Navy’s commander in chief on the Great Lakes and surrounding waters. Perhaps because he thought Pring a little too aggressive, Yeo replaced him almost on the eve of battle—first with Captain Peter Fisher, who lasted but six weeks in Yeo’s good graces, and then with Captain George Downie. Two years older than Macdonough, thirty-three-year-old Downie had had a similar career and shared an Irish heritage. Born in the county of Ross, Ireland, Downie entered the Royal Navy as a midshipman and served on a number of vessels, particularly in the West Indies. By 1804 he was a lieutenant aboard the frigate HMS Sea Horse and in due course worked his way up to post captain, the rank he held when the Admiralty dispatched him to Montreal in command of a squadron of transports carrying components for Yeo’s shipbuilding efforts on Lake Ontario. Yeo sent him to Lake Champlain at the eleventh hour.9

Downie’s new flagship—and the match for the Saratoga—was the twelve-hundred-ton, 160-foot Confiance (Confidence), named by Sir James Yeo not out of any idle boast—Yeo certainly had no room to make any—but rather out of mere sentiment as the namesake of his first command. Planned for a crew of 325, she carried thirty long twenty-four-pounders, six thirty-two-pound carronades, and a long twenty-four on a pivot. Her broadside weight bested Saratoga by at least sixty-six pounds and perhaps as many as ninety-six. (There is some evidence that her carronades were actually forty-two-pounders.) But what really provided an advantage was an onboard furnace for heating shot. Confiance had been on the water only a week when Downie stepped aboard her and assumed command of the Lake Champlain squadron on September 2, 1814. Carpenters were still at work on his flagship, and she was as new and green to the lake as he was.

Joining Confiance were the brig Linnet and two sloops. The eighty-five-foot Linnet remained under Lieutenant Pring’s command and was about the size of the Ticonderoga, mounting sixteen long twelve-pounders. If the sloops Chub and Finch looked familiar, they should have. These were the former American sloops Eagle and Growler lost the year before by Lieutenant Smith. Chub carried ten eighteen-pound carronades and one long six-pounder; and Finch six eighteen-pound carronnades, four long six-pounders, and one short eighteen-pounder. The British also had an assortment of twelve gunboats, the larger ones of which carried both a long gun and one carronade.

In all, this amounted to sixteen British vessels throwing a broadside of 1,192 pounds—at first blush almost exactly equal to that of the Americans. But upon closer inspection, the allotment of long guns versus carronades was almost the reverse of the Americans, the British fleet having 55 percent of its armament in long guns. Again, Theodore Roosevelt in The Naval War of 1812 painstakingly did the math and the analysis, but the bottom line was simple: out on the lake at long range, Downie held an advantage. At close range, where his carronades could pound away, the advantage belonged to Macdonough.10

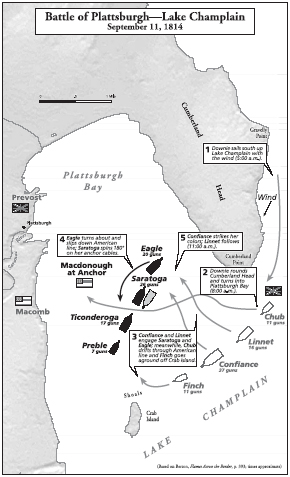

The biggest difference between the two fleets, however, was that time was on Macdonough’s side. He held the southern lake and could afford to wait. Let the British come. It was Downie who was under pressure from General Prevost to do something. Accordingly, Macdonough sought out the deep waters of Plattsburgh Bay. Later, there would be great debate over how important Macomb’s artillery on the western shores of the bay was to supporting Macdonough’s anchorage and vice versa, but the bay itself was a natural defensive position. Roughly two miles wide, it opened to the south with the main shore and mouth of the Saranac River to the west and Cumberland Head dividing it from the main lake on the east. This meant that any north wind favorable to the British for sailing up the lake (to the south) would quickly become a headwind as their ships rounded the head and entered the bay. Crab Island and some extensive shoals extended from the mainland at the mouth of the bay and further restricted the movements of any ships entering it.

Macdonough took advantage of this geography to anchor his fleet just inside the mouth of the bay in a line extending roughly southwest to northeast between Crab Island and Cumberland Head. This meant that any enemy entering the bay would likely have to do so bows on—sailing straight into his broadsides. The Eagle lay on the northern end of the line, close enough to Cumberland Head that any attempt to run between her and the shore would place the opponent under heavy fire. Saratoga came next in line, but as his heavy weapon, Macdonough arranged a system of anchors and winches that permitted the ship to be pivoted to face any direction that future circumstances should warrant. Ticonderoga was anchored south of Saratoga, followed by Preble, whose task it was to guard the shallow passage between the main fleet and the shoals of Crab Island and prevent any flanking maneuver from that direction.11

Just why Sir George Prevost was so determined to wait for the Royal Navy and have Downie sail into this hornet’s nest is debatable. Certainly, his army of more than ten thousand veterans should have been easily able to steamroller over Macomb’s troops no matter how effective their breastworks above the Saranac may have been. That is exactly what Prevost’s brigade commanders, major generals Frederick Robinson, Thomas Brisbane, and Manley Power, expected him to order. But whereas they had made their marks on the battlefields of Spain under the Iron Duke, Prevost had made his in administrative and defensive operations in North America. To take orders from someone who had only colonial experience, and was younger than any of them at that, galled to say the least. But at least let there be orders. “It appears to me,” Robinson later confessed to his journal, “that the army moved against Plattsburgh without any regularly digested plan by Sir George Prevost.”12

Actually, Sir George considered ordering Robinson’s brigade to storm the American position upon arriving in Plattsburgh, but hesitated when his intelligence failed to report the whereabouts of fords across the Saranac or the distance of the American fortifications beyond its bank. By the time this information became available, Prevost had determined to wait for Downie. “It is of the highest importance that the ships, vessels, and gunboats, under your command,” Prevost wrote to Downie shortly after Downie’s arrival on the lake, “should combine a co-operation with the division of the army under my command. I only wait for your arrival to proceed against General Macomb’s last position on the south bank of the Saranac.”13

Downie replied that he was willing to do so, but that Confiance was far from ready for action. Carpenters were still at work, and he was doing his best to scrape together a crew. Hastily assembled, it was to be like that of the Chesapeake when Lawrence hurriedly sailed out to engage Shannon, unknown to the ship and largely unknown to one another. “Until she is ready,” Downie told Sir George, “it is my duty not to hazard the squadron before an enemy who will be superior in force.”14

Why Downie thought Macdonough’s force superior is open to question. Perhaps it was merely his way of buying a few extra days. Certainly the Confiance needed every hour that could be bought, and in her rookie state she may well have been inferior to Macdonough’s seasoned hands aboard Saratoga. Confiance was still being rigged as she was towed up the lake to join the remainder of Downie’s squadron off Chazy. “It scarcely needs the habit of a naval seaman to recognize,” recounted Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan long after the fact, “that even three or four days’ grace for preparation would immensely increase efficiency.”

But Downie was not to have those days. Now it was Sir George’s turn to adopt an icy tone. The next day, September 9, Prevost replied: “In consequence of your communication of yesterday I have postponed action until your squadron is prepared to co-operate. I need not dwell with you on the evils resulting to both services from delay.” Prevost was senior in rank and years, not to mention being governor-general of Canada. What was poor Downie to do?

Beaten down, the young captain prepared to sail at midnight on the evening of the ninth, but strong headwinds prevented him from doing so. When he learned of this most recent delay, Sir George’s words carried even more bite than the wind. Noting that his troops were ready to storm Macomb’s position at the same moment as Downie commenced his attack, Prevost chastised: “I ascribe the disappointment I have experienced to the unfortunate change of wind and shall rejoice to learn that my reasonable expectations have been frustrated by no other cause.”

“This letter does not deserve an answer,” remarked Downie hotly to Pring, “but I will convince him that the naval force will not be backward in their share of the attack.” Downie arranged to scale his guns—fire powder cartridges without shot to clean out the bores—to signal his approach so that Sir George would know when to begin his coordinated attack. He hoped this would cause the American ships to flee their protected anchorage or at the very least cause them confusion. To Pring, however, Downie admitted that he would much rather fight on the open waters of the lake.15

In the wee hours of September 11, 1814, with the wind from the northeast, Downie’s little squadron swept up the lake. At five o’clock, upwind and at a distance of some six or seven miles from Prevost’s position, Downie scaled his guns. There! Let Sir George know that the Royal Navy was en route and prepared to do its fair share. Two and one-half hours later off Cumberland Head, the British squadron hove to so that the smaller gunboats could catch up to the bigger vessels. Downie took advantage of the pause to be rowed in his gig around the tip of Cumberland Head. This allowed him to peer into Plattsburgh Bay and personally ascertain the American position.

The order of the American line from north to south was just as Macdonough had planned: Eagle, Saratoga, Ticonderoga, and Preble. Lest anyone forget after two years of war what all the fighting was about, Macdonough ran a signal up the mast of his flagship that proclaimed, “Impressed seamen call on every man to do his duty.”16

Downie’s plan was to sweep around Cumberland Head with Finch leading Confiance, Linnet, and Chub. When the line tacked to starboard and turned into the wind to sail into the bay, this would put Linnet and Chub in the van to attack Eagle. Confiance would move out in front of the line, assist with a broadside against Eagle, and then anchor across the Saratoga’s bow and rake her. With the three strongest British ships arrayed against the two strongest Americans, Finch and the gunboats would be left to harry Ticonderoga and Preble and keep them out of the main action. Meanwhile, Downie fully expected Prevost’s men to have seized the heights above the Saranac River and turned the captured American batteries onto the rear of the American fleet. The American vessels would be either trapped or forced to run for the open lake, where Downie’s long guns would show their advantage.

Battle of Plattsburgh—Lake Champlain

Confidence! It might work after all. But as Confiance rounded Cumberland Head and headed upwind to lead the attack, there was no evidence of Sir George’s army rushing to attack the heights. Downie quickly became painfully aware that he was alone. Alone, but committed. Whatever thoughts he now had for Sir George would soon go with him to his grave.

The British line stood into Plattsburgh Bay, Linnet leading. The first broadside from her long twelves fell short of Saratoga except for one round. That one shot hit a hen coop on the Saratoga’s deck and blew it apart, releasing the gamecock that was inside. Instead of cowing, the cock flapped his wings and crowed loudly. The Saratoga’s crew cheered just as loudly, and Macdonough fired the first gun in reply.

Confiance’s first broadside is said to have struck down a fifth of the Saratoga’s crew, evidence that had a duel occurred between these two ships in open waters, Confiance’s heavier broadside weight might have told the tale. But in the narrow confines of Plattsburgh Bay, the wind quickly died and Downie’s flagship was forced to anchor some five hundred yards from the American line. Pring’s Linnet reached the Eagle and closed with her, but Chub’s support was not forthcoming. Chub suffered extensive damage to her sails and rigging and ended up drifting through the American line before she could anchor. Finch had trouble keeping into the wind and failed to close with Ticonderoga. She eventually went aground on Crab Island. British gunboats scurried about and forced Preble from her anchorage at the end of the American line. Thus, the deciding contest quickly shaped up to be between Saratoga and Confiance, and Eagle and Linnet.

The fighting was fast and furious. Twice the Saratoga was set afire by hot shot heated in the Confiance’s furnace. Although out-weighted, Saratoga answered Confiance broadside for broadside. One American shot struck the muzzle of a British cannon and knocked it off its carriage. It fell against Captain Downie, pinning him dead and flattening his watch in the process. Eagle soon became so pummeled that Captain Henley cut her anchor cable and caught enough wind in her topsails to drift south around Saratoga, turning about as he did so. Once back in the line, Henley reanchored Eagle and brought her undamaged side to bear on the enemy. This enabled Eagle to pour fire into Confiance, but it also freed up Linnet to hammer Saratoga from the north.

Now Macdonough did a similar maneuver. Without getting under way, he spun his ship 180 degrees using winches and the anchor chains and brought her uninjured broadside to bear on Confiance. Downie’s executive officer, Lieutenant Henry Robertson, who assumed command of the Confiance upon Downie’s death, attempted a similar maneuver. Confiance, however, had dropped anchor quickly upon entering the fray, and without the careful positioning and rigging Macdonough had done aboard Saratoga. Robertson was able to execute only half of the turn, leaving his ship at right angles to a deady raking fire. “The ship’s company,” reported Robertson afterward, “declared they would stand no longer to their quarters, nor could the officers with their utmost exertions rally them.”

Water was pouring into Confiance. Her guns were run in on the port side to throw some weight to starboard and bring the cannonball holes on her port side out of the water. Much of Saratoga’s rigging and several of her masts were shot away, but she was clearly the victor. Lieutenant Robertson had no choice but to strike his colors at 11:00 A.M., more than two hours after the engagement began. Pring struck Linnet’s colors fifteen minutes later, and the Battle of Lake Champlain was over. There was still no sign of General Prevost’s troops on the ramparts above the bay.

According to Macdonough, Saratoga had 55 round shot in her hull, Confiance 105. Casualties were particularly difficult to calculate, in part because of the variety of last-minute recruits on both sides. Perhaps the most reliable estimate is fifty-two Americans killed and fifty-eight wounded, and fifty-seven British killed and seventy-two wounded. Seventeen British officers and upwards of three hundred seamen were also taken prisoner. Captain Macdonough graciously returned the proffered swords of the surviving British officers, and Lieutenant Pring was glowing in his praise of the Americans’ prompt and cordial treatment of the British wounded.

Placing his trust first and foremost where it had always been, Macdonough reported that “the Almighty has been pleased to grant us a signal victory on Lake Champlain in the capture of one frigate, one brig, and two sloops of war of the enemy.” Echoing that sentiment, no less a naval authority and historian than Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan wrote almost a century later that “the battle of Lake Champlain, more nearly than any other incident of the War of 1812, merits the epithet ‘decisive.’” But where was Sir George Prevost?17

Major General Frederick Robinson’s brigade and that of Major General Manley Power had been waiting since an hour before dawn to cross the Saranac and attack Macomb’s left flank, planning to drive him from his position. Robinson himself had heard Downie scale his guns while riding to Prevost’s headquarters to receive his final orders. But Prevost ordered that the attack not begin until 10:00 A.M. When Robinson finally led his troops forward at that late hour, there was still confusion as to which road to take to ford the Saranac. An hour passed before Robinson neared the ford, and by then, he recorded, “we heard three cheers from the Plattsburgh side.” Sending an aide to ascertain which side was cheering, Robinson soon realized how dreadfully late Prevost’s orders had been.18

Prevost realized it, too. With thoughts of Saratoga no doubt echoing in his brain, he finally moved with alacrity—but in the direction not even General Macomb had expected. Dispatching a hasty order to Robinson, Prevost noted the defeat of Downie’s fleet and ordered him to “immediately return with the troops under your command.” If Robinson was surprised, Macomb was even more so. By nightfall, the largest British army ever to tread American soil had burned surplus stores and munitions and started back to Canada. Macomb hardly had time to blink, and they were gone. He reported to the War Department on the valiant defense his men had made, but it was really Sir George’s order to retreat that had won him the day.19

Unlike the Battle of Lake Erie where the victors quarreled over the roles of Perry and Elliott, on Lake Champlain it was the vanquished who refought the battle with a vengeance. Lieutenant Pring, though he had done all that he could to support Downie and Prevost’s rushed strategy, was hauled before the requisite court-martial. Pring was exonerated only when the navy decided to blame the army for its loss. Sir George Prevost was summoned home to England to face his own court-martial. Speaking for the Royal Navy, Sir James Yeo had been particularly harsh on Prevost during Pring’s review. Yeo maintained that had Prevost’s troops stormed Macomb’s defenses as Downie rounded Cumberland Head, Macdonough’s squadron would have been forced to quit the bay. What Prevost should have done, the navy maintained, was to use his vast superiority in numbers—able veterans at that—to take the works across the Saranac and drive the American fleet out from the protection of the bay and into the superior force of the Confiance and her consorts.

Prevost certainly had his detractors, but he also had his supporters, among them the Duke of Wellington. “Whether Sir George Prevost was right or wrong in his decision at Lake Champlain is more than I can tell…,” the Iron Duke wrote the following December. But, continued Wellington, “I have told the Ministers repeatedly that a naval superiority on the lakes is a sine qua non of success in war on the frontier of Canada, even if our object should be solely defensive.” Perhaps recognizing that there was more to waging war in the colonies than first met the eye, the Duke of Wellington, it should be noted, turned down an offer to replace Sir George Prevost as governor-general of Canada. Wellington was content to rest upon his Napoleonic laurels until called upon to deliver the coup de grâce at Waterloo the following June.20

Prevost’s court-martial never convened because the defendant died the evening before it was to commence, no doubt sped to his grave by harsh critics, some of whom—such as Yeo—had little room to talk. Meanwhile, Thomas Macdonough became the toast of the American nation. “In one month from a poor lieutenant I became a rich man,” Macdonough himself was to say. “Down to the time of the Civil War,” Theodore Roosevelt later wrote, “he [Macdonough] is the greatest figure in our naval history” and the fight that day in Plattsburgh Bay the “greatest naval battle of the war.”21

Considering the company in which Macdonough found himself, that praise may have surprised even him. But Roosevelt went further. Giving Perry his due for the victory off Put-in Bay, Roosevelt nonetheless wrote: “It will always be a source of surprise that the American public should have so glorified Perry’s victory over an inferior force, and have paid comparatively little attention to Macdonough’s victory, which really was won against decided odds in ships, men, and metal.”22 Perhaps Thomas Macdonough should have come up with a catchier victory report of his own.

And perhaps history has indeed given Macdonough short shrift. Had not Macomb and Macdonough made their stand, a British general less defensively inclined than Sir George Prevost may well have ended up spending the following winter in Albany if not New York City. At the very least, a British victory at Plattsburgh and on Lake Champlain would have given the Madison administration another flank to worry about while they had their hands full with British dalliances about Washington and Baltimore. And the Union Jack left flying on American soil would have both given credence to Sir George’s initial orders to tend to the security of Lower Canada and provided a territorial bargaining chip at the peace table. None of this happened. The gamecock aboard the Saratoga had reason to crow. “This is a proud day for America,” noted Lieutenant Colonel John Murray of the British army, “the proudest day she ever saw.”23