THE FLYWHEEL WITHIN A FRAMEWORK

A Map for the Journey from Good to Great

I wrote this monograph to share practical insights about the flywheel principle that became clear in the years after first writing about the flywheel effect in chapter 8 of Good to Great. I decided to create this monograph because I’ve witnessed the power of the flywheel, when properly conceived and harnessed, in a wide range of organizations: in public corporations and private companies, in large multinationals and small family businesses, in military organizations and professional sports teams, in school systems and medical centers, in investment firms and philanthropic endeavors, in social movements and nonprofits.

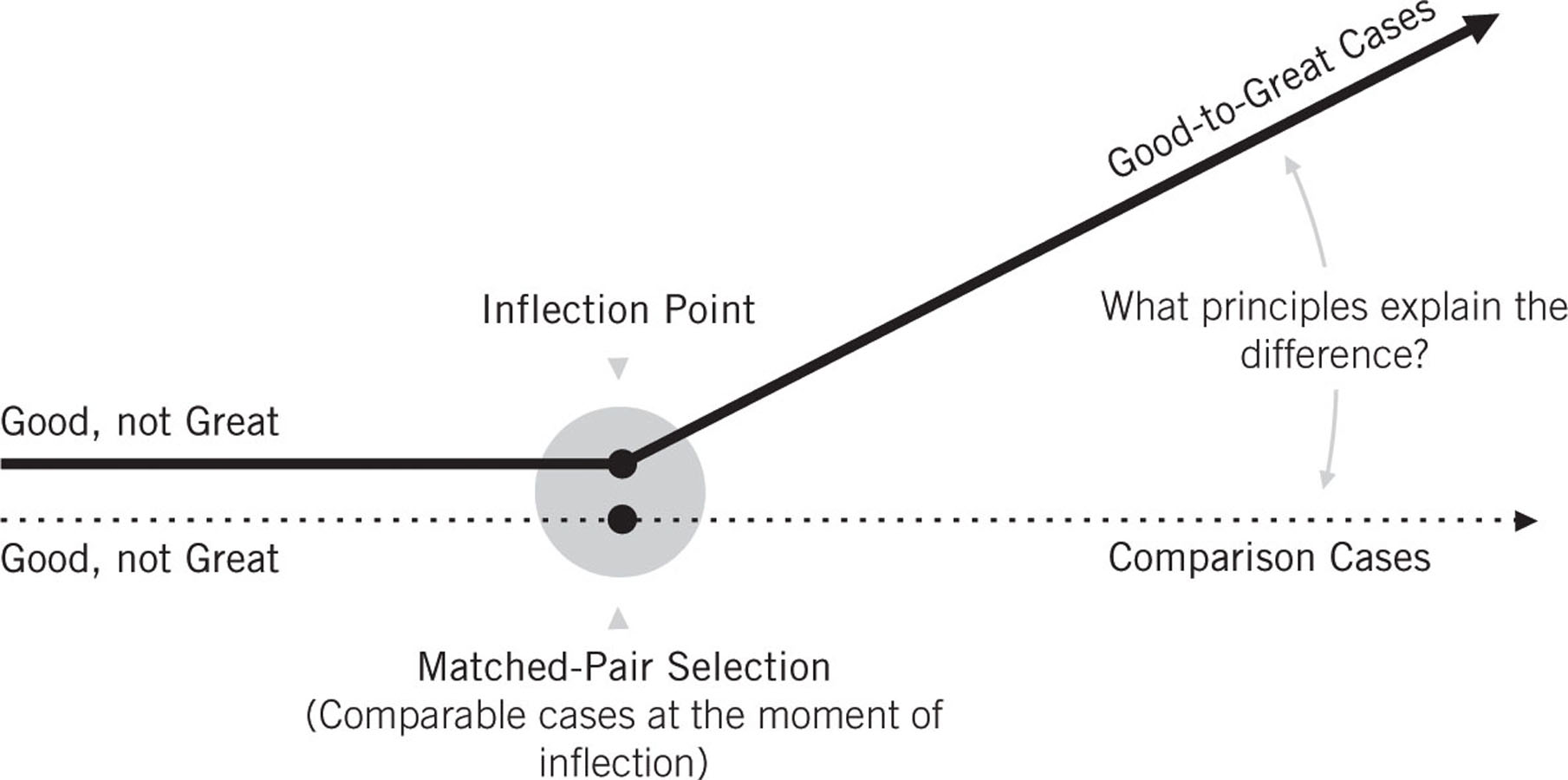

Yet the flywheel effect alone does not make an organization great. The flywheel fits within a framework of principles we uncovered through more than a quarter-century of research into the question of what makes a great company tick. We derived these principles using a rigorous matched-pair research method, comparing companies that became great with companies (in similar circumstances) that did not. We’d systematically analyze the histories of the contrasting cases and ask, “What explains the difference?” (See nearby diagram, “The Good-to-Great Matched-Pair Research Method.”)

THE GOOD-TO-GREAT MATCHED-PAIR RESEARCH METHOD

My research colleagues and I applied the historical matched-pair research method in four major studies, each using a different lens, that resulted in four books: Built to Last (coauthored with Jerry I. Porras), Good to Great, How the Mighty Fall, and Great by Choice (coauthored with Morten T. Hansen). We also extended the principles beyond business in the monograph Good to Great and the Social Sectors.

An overarching theme across our research findings is the role of discipline in separating the great from the mediocre. True discipline requires the independence of mind to reject pressures to conform in ways incompatible with values, performance standards, and long-term aspirations. The only legitimate form of discipline is self-discipline, having the inner will to do whatever it takes to create a great outcome, no matter how difficult. When you have disciplined people, you don’t need hierarchy. When you have disciplined thought, you don’t need bureaucracy. When you have disciplined action, you don’t need excessive controls. When you combine a culture of discipline with an ethic of entrepreneurship, you create a powerful mixture that correlates with great performance.

To build an enduring great organization—whether in the business or social sectors—you need disciplined people who engage in disciplined thought and take disciplined action to produce superior results and make a distinctive impact in the world. Then you need the discipline to sustain momentum over a long period of time and to lay the foundations for lasting endurance. This forms the backbone of the framework, laid out as four basic stages:

Stage 1: Disciplined People

Stage 2: Disciplined Thought

Stage 3: Disciplined Action

Stage 4: Building to Last

Each of the four stages consists of two or three fundamental principles. The flywheel principle falls at a central point in the framework, right at the pivot point from disciplined thought into disciplined action. I’ve provided a brief description of the principles below.

STAGE 1: DISCIPLINED PEOPLE

LEVEL 5 LEADERSHIP

Level 5 leaders display a powerful mixture of personal humility and indomitable will. They’re incredibly ambitious, but their ambition is first and foremost for the cause, for the organization and its purpose, not for themselves. While Level 5 leaders can come in many personality packages, they’re often self-effacing, quiet, reserved, and even shy. Every good-to-great transition in our research began with a Level 5 leader who motivated people more with inspired standards than inspiring personality. This concept is first developed in the book Good to Great and further refined in the monograph Good to Great and the Social Sectors.

FIRST WHO, THEN WHAT—GET THE RIGHT PEOPLE ON THE BUS

Those who lead organizations from good to great first get the right people on the bus (and the wrong people off the bus) and then figure out where to drive the bus. They always think first about “who” and then about “what.” When you’re facing chaos and uncertainty, and you cannot possibly predict what’s coming around the corner, your best “strategy” is to have a busload of people who can adapt and perform brilliantly no matter what comes next. Great vision without great people is irrelevant. This concept is first developed in the book Good to Great and further refined in the monograph Good to Great and the Social Sectors.

STAGE 2: DISCIPLINED THOUGHT

GENIUS OF THE AND

Builders of greatness reject the “Tyranny of the OR” and embrace the “Genius of the AND.” They embrace both extremes across a number of dimensions at the same time. For example, creativity AND discipline, freedom AND responsibility, confront the brutal facts AND never lose faith, empirical validation AND decisive action, bounded risk AND big bets, productive paranoia AND a bold vision, purpose AND profit, continuity AND change, short term AND long term. This concept is first introduced in the book Built to Last and further developed in the book Good to Great.

CONFRONT THE BRUTAL FACTS—THE STOCKDALE PARADOX

Productive change begins when you have the discipline to confront the brutal facts. The best mind frame to have for leading from good to great is represented in the Stockdale Paradox: Retain absolute faith that you can and will prevail in the end, regardless of the difficulties, and at the same time, exercise the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be. This concept is fully developed in the book Good to Great.

THE HEDGEHOG CONCEPT

The Hedgehog Concept is a simple, crystalline concept that flows from deep understanding about the intersection of the following three circles: (1) what you’re deeply passionate about, (2) what you can be the best in the world at, and (3) what drives your economic or resource engine. When a leadership team becomes fanatically disciplined in making decisions consistent with the three circles, they begin to generate momentum toward a good-to-great inflection. This includes not only the discipline of what to do, but equally, what not to do and what to stop doing. This concept is first developed in the book Good to Great and further refined in the monograph Good to Great and the Social Sectors.

STAGE 3: DISCIPLINED ACTION

THE FLYWHEEL

No matter how dramatic the end result, building a great enterprise never happens in one fell swoop. There’s no single defining action, no grand program, no one killer innovation, no solitary lucky break, no miracle moment. Rather, the process resembles relentlessly pushing a giant, heavy flywheel, turn upon turn, building momentum until a point of breakthrough, and beyond. To maximize the flywheel effect, you need to understand how your specific flywheel turns. The flywheel effect is first developed in the book Good to Great, and its application is fully developed in this monograph.

20 MILE MARCH

Companies that thrive in a turbulent world self-impose rigorous performance marks to hit with relentless consistency—like walking across a gigantic continent by marching at least twenty miles a day, every day, regardless of conditions. The march imposes order amidst disorder, discipline amidst chaos, and consistency amidst uncertainty. For most organizations, a one-year 20 Mile March cycle works well, although it could be shorter or longer. But whatever the cycle, the 20 Mile March requires both short-term focus (you have to hit the march this cycle) and long-term building (you have to hit the march every subsequent cycle for years to decades). As such, it’s a rarified form of disciplined action that correlates strongly with achieving breakthrough performance and sustaining flywheel momentum. This concept is fully developed in the book Great by Choice.

FIRE BULLETS, THEN CANNONBALLS

The ability to scale innovation—to turn small, proven ideas (bullets) into huge successes (cannonballs)—can provide big bursts of momentum. First, you fire bullets (low-cost, low-risk, low-distraction experiments) to figure out what will work—calibrating your line of sight by taking small shots. Then, once you have empirical validation, you fire a cannonball (concentrating resources into a big bet) on the calibrated line of sight. Calibrated cannonballs correlate with outsized results; uncalibrated cannonballs correlate with disaster. Firing bullets, then cannonballs, is a primary mechanism for expanding the scope of an organization’s Hedgehog Concept and extending its flywheel into entirely new arenas. This concept is fully developed in the book Great by Choice.

STAGE 4: BUILDING TO LAST

PRODUCTIVE PARANOIA

The only mistakes you can learn from are the ones you survive. Leaders who navigate turbulence and stave off decline assume that conditions can unexpectedly change, violently and fast. They obsessively ask, “What if? What if? What if?” By preparing ahead of time, building reserves, preserving a margin of safety, bounding risk, and honing their discipline in good times and bad, they handle disruptions from a position of strength and flexibility. Productive paranoia helps inoculate organizations from falling into the five stages of decline that can derail the flywheel and destroy an organization. Those stages are (1) Hubris Born of Success, (2) Undisciplined Pursuit of More, (3) Denial of Risk and Peril, (4) Grasping for Salvation, and (5) Capitulation to Irrelevance or Death. Productive paranoia is fully developed in the book Great by Choice, and the five stages of decline are fully developed in the book How the Mighty Fall.

CLOCK BUILDING, NOT TIME TELLING

Leading as a charismatic visionary—a “genius with a thousand helpers” upon whom everything depends—is time telling. Shaping a culture that can thrive far beyond any single leader is clock building. Searching for a single great idea upon which to build success is time telling. Building an organization that can generate many great ideas is clock building. Leaders who build enduring great companies tend to be clock builders, not time tellers. For true clock builders, success comes when the organization proves its greatness not just during one leader’s tenure but also when the next generation of leadership further increases flywheel momentum. This concept is fully developed in the book Built to Last.

PRESERVE THE CORE/STIMULATE PROGRESS

Enduring great organizations embody a dynamic duality. On the one hand, they have a set of timeless core values and core purpose (reason for being) that remain constant over time. On the other hand, they have a relentless drive for progress—change, improvement, innovation, and renewal. Great organizations understand the difference between their core values and purpose (which almost never change), and operating strategies and cultural practices (which endlessly adapt to a changing world). The drive for progress often manifests in BHAGs (Big Hairy Audacious Goals) that stimulate the organization to develop entirely new capabilities. Many of the best BHAGs come about as a natural extension of the flywheel effect, when leaders imagine how far the flywheel can go and then commit to achieving what they imagine. This concept is first developed in the book Built to Last and further developed in the book Good to Great.

10X MULTIPLIER

RETURN ON LUCK

Finally, there’s a principle that amplifies all the other principles in the framework, the principle of return on luck. Our research showed that the great companies were not generally luckier than the comparisons—they didn’t get more good luck, less bad luck, bigger spikes of luck, or better timing of luck. Instead, they got a higher return on luck, making more of their luck than others. The critical question is not, will you get luck? But what will you do with the luck that you get? If you get a high return on a luck event, it can add a big boost of momentum to the flywheel. Conversely, if you are ill-prepared to absorb a bad-luck event, it can stall or imperil the flywheel. This concept is fully developed in the book Great by Choice.

THE OUTPUTS OF GREATNESS

The above principles are the inputs to building a great organization. You can think of them almost as a “map” to follow for building a great company or social-sector enterprise. But what are the outputs that define a great organization? Not how you get there, but what is a great organization—what are the criteria of greatness? There are three tests: superior results, distinctive impact, and lasting endurance.

SUPERIOR RESULTS

In business, performance is defined by financial results—return on invested capital—and achievement of corporate purpose. In the social sectors, performance is defined by results and efficiency in delivering on the social mission. But whether business or social, you must achieve top-flight results. To use an analogy, if you’re a sports team, you must win championships; if you don’t find a way to win at your chosen game, you cannot be considered truly great.

DISTINCTIVE IMPACT

A truly great enterprise makes such a unique contribution to the communities it touches and does its work with such unadulterated excellence that, if it were to disappear, it would leave a gaping hole that could not be easily filled by any other institution on the planet. If your organization went away, who would miss it, and why? This does not require being big; think of a small but fabulous local restaurant that would be terribly missed if it disappeared. Big does not equal great, and great does not equal big.

LASTING ENDURANCE

A truly great organization prospers over a long period of time, beyond any great idea, market opportunity, technology cycle, or well-funded program. When clobbered by setbacks, it finds a way to bounce back stronger than before. A great enterprise transcends dependence on any single extraordinary leader; if your organization cannot be great without you, then it is not yet a truly great organization.

Finally, I caution against ever believing that your organization has achieved ultimate greatness. Good to great is never done. No matter how far we have gone or how much we have achieved, we are merely good relative to what we can do next. Greatness is an inherently dynamic process, not an end point. The moment you think of yourself as great, your slide toward mediocrity will have already begun.