A.2 Additional material from the main manuscript

A.2.i Ransome’s own textual corrections, and editorial emendations (sample pages, annotated)

[fols 131–41]

[fol. 131] |

It is not a question merely of marked personality. It was too wilful1 an illusion for that. It is a question of Stevenson’s attitude of mind towards his work, which allowed him in his own view of what he was doing, to separate matter and manner, as few other writers have ever been able2 so to separate them. Remembering the significant phrase in the paragraph where he describes the novelist’s task: ‘for3 so long a time you must keep at command the same quality of style’ – we can find a score of other sentences indicative of this preoccupation. He speaks for instance of ‘the constipated mosaic manner’ he needed for Weir of Hermiston,4 and had adopted5 successfully in The Ebb Tide. Then there were The New Arabian Nights and Otto, ‘pitched pretty high and stilted’. Then the pathetic6 little episode [fol. 132] of Mr Somerset, and again flat, direct statements as in the letter IV 231.7 |

[fol. 133] |

We8 begin to see now what an intricate affair is any perfect passage; how many faculties, whether of taste or pure reason, must be held upon the stretch to make it; and why, when it is made, it should afford us so complete a pleasure. From the arrangement of according letters, which is altogether arabesque and sensual, up to the architecture of the elegant and pregnant sentence, which is a vigorous act of the pure intellect, there is scarce a faculty in man but has been exercised. We need not wonder, then, if perfect sentences are rare, and perfect pages rarer.9 |

[fol. 138] |

‘Every book is, in an intimate sense, a circular letter to the friends of him who writes it.16 They alone take his meaning; they find private messages, assurances of love, and expressions of gratitude, dropped for them in every corner. The public is but a generous patron who defrays17 the postage.’ The first of these sentences from the dedication of Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes is strictly true; except in a few rare cases, and of the books of great and isolated man. The third is an ingenious, charming corollary to the second. And the second is not by any means generally true, though it is so18 of much of Stevenson’s own work, and partly explains its peculiar intimate quality. He was thinking of Otto when he wrote to Mr. Gosse19 that it was a deadly fault ‘to forget that art is a diversion and a decoration, that no triumph or effort is of value, nor anything worth reaching except charm’; but20 the opinion had long been his, and the expression of it is in the manner of writing, dangerously infectious, easily recognisable, that he [fol. 139] early developed for himself. |

A.2.ii Ransome’s (incomplete) Book-list

[Missing from the list are Colvin’s 1911 edition of Stevenson’s Letters, and the 1911 edition of Graham Balfour’s Life of Robert Louis Stevenson, sources which Ransome is known to have used.]

[fols 325–6]

Books

A Chronicle of Friendship [1873–1900], by Will H[icok] Low. Hodder & Stoughton, 1908.

Robert Louis Stevenson. A Record, An Estimate, And A Memorial, by Alexander H. Japp, LLD. etc. T. Werner Laurie, 1905.

Memories of Vailima, by Isobel Strong and Lloyd Osbourne. Constable, 1903.

In the Tracks of R. L. Stevenson and Elsewhere in Old France, by J. A. Hammerton. Arrowsmith, 1907.

With Stevenson in Samoa, by H. J. Moors. Fisher Unwin, 1910.

Recollections of Robert Louis Stevenson in the Pacific, by Arthur Johnstone. Chatto and Windus, 1905.

Robert Louis Stevenson, An Essay, by Leslie Stephen. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, no date. [1903]

In Stevenson’s Samoa, by Marie Fraser, 2nd edition. Smith Elder, 1895.

Robert Louis Stevenson, by L. Cope Cornford. Blackwood, 1899.

Robert Louis Stevenson, by Eve Blantyre Simpson. T. N. Foulis, 1905.

Robert Louis Stevenson, by Margaret Moyes Black. Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, 1898.

Robert Louis Stevenson. Bookman Booklet (W. Robertson Nicoll, G. K. Chesterton). Hodder & Stoughton, 1902.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh Days, by Eve Blantyre Simpson. 2nd ed., Hodder and Stoughton, 1898.

An Edinburgh Eleven, by J. M. Barrie, 3rd edition. Hodder and Stoughton, 1896.

Letters from Samoa, by Mrs. M. I. Stevenson. Methuen, [1906].

From Saranac to the Marquesas, by Mrs M. I. Stevenson. Methuen, 1903.

Robert Louis Stevenson, A Life Study in Criticism, by H. Bellyse Baildon. Chatto and Windus, 1901.

The Home and Early Haunts of R. L. Stevenson, by Margaret Armour. W. H. White, 1895.

The Faith of Robert Louis Stevenson, by John Kelman. Jr. M. A. Oliphant Anderson & Ferrier, 1903.

[fol. 100] |

[a draft passage for p. 82] Well, gentlemen, it seems this way to me: Stevenson was first and last a man of convictions – in fact he always acted promptly and vigorously when he reached a conclusion that satisfied his own mind – but his mental make-up was such that he always took the side of the under-dog in any fight that arose, without waiting to inquire whether the under-dog had the right of it, or was in the wrong. That was the man, gentleman; and I know from personal experience that he did not understand what fear was, when he defended what he thought was right. |

[fol. 164] |

[The quotation appears in a slightly different formulation on p. 103.] |

[fol. 173] |

[a draft sentence for part of p. 62] |

[fol. 187] |

[an opener perhaps for p. 151] |

[fol. 378] |

[an earlier version of paragraph on p. 84] |

A.2.iv Quotations copied by Ransome and notes by him that have not been used in the running text

[fol. 360] |

‘What a man spends upon himself he shall have earned by services to the race.’ |

[fol. 369] |

He once successfully worked out a theory for a detective in the criminal case. |

[fol. 373] |

‘In my view, one dank, dispirited word is harmful, a crime of lèse-humanité, a piece of acquired evil; every gay, every bright word or picture, like every pleasant air of music, is a piece of pleasure set afloat; the reader catches it, and, if he be healthy, goes on his way rejoicing; and it is the business of art so to send him, as often as possible.’ To W. Archer, Oct. 28, 1885, Bournemouth [Letters], II, 248.” |

[fol. 374] |

April 20, 1893. Mrs Strong writes: ‘I was pottering about my room this morning when Louis came in with the remark that he was a gibbering idiot. I have seen him in this mood before, when he pulls out hairpins, tangles up his mother’s knitting, and interferes in whatever his womankind are engaged upon. So I gave him employment in tidying a drawer all the morning – talking the wildest nonsense all the time, and he was babbling on when Sesimo came in to tell us lunch was ready; his very reverential, respectful manner brought the Idiot Boy to his feet at once, and we all went off laughing to lunch.’ Memories of Vailima, pp. 31, 32. |

[fol. 379] |

Travel. Oct 22. ‘If we didn’t travel now and then, we should forget what the feeling of life is. The very cushion of a railway carriage – “the things restorative to the touch”.’ To Baxter, Dunblane, March 5, 1872. Letters, I, 34. |

[fol. 380] |

‘spontaneous lapse of coin’ |

[fol. 382] |

Of art says Stevenson, “The direct returns – the wages of the trade are small, but the indirect – the wages of the life – are incalculably great. No other business offers a man his daily bread upon such joyful terms.” Across the Plains, 185. |

[fol. 383] |

His uncle Alan, when building lighthouses, used to read Quixote, Aristophanes and Dante, each in the language of its birth. |

[fol. 384] |

Trust |

[fol. 387] |

‘I have that peculiar and delicious sense of being born again in an expurgated edition which belongs to ‘convalescence.’ Oct. 29, [Letters,] I, 259. |

A.2.v Significant working notes for sections of text

[fol. 11] |

[Notes for Part I of the book; the ticks indicate sections written.] Biographical Summary |

I |

General ✓ |

II |

Birth and Childhood ✓ |

III |

School days |

IV |

University & Edinburgh days. To advocate. ✓ |

V |

Ordered South & Health ✓ |

VI |

Fontainebleau ……✓ |

VI [sic] |

Monastier. & Inland Voyage |

VII |

Emigration. San Francisco. Monterey & Marriage. ✓ |

VIII |

Scotland & Davos. War game. Printing. ✓ |

IX |

Bournemouth ✓ ? |

X |

2nd voyage to America. At Saranac. New Jersey. Cat boat sailing ✓ |

XI |

Yacht Casco. Cruising in the South Seas …✓ |

XII |

Vailima ✓ |

XIII |

Death & Summary. ✓ |

[This check-list follows]

University ✓ |

|

With a view to his engineering, he took scientific & mathematics classes instead of the humanities. ✓ |

|

1871, April. |

Told his father he did not want to be an engineer. His father stoically agreed and S. was to be an Advocate. |

1872 |

Passed public exam for Scottish Bar. Spent some time in an office learning conveyancing. |

[fol.48] |

July 14. Passed as Advocate |

[fol. 174] Early Criticism |

aet. 38, Shaw [Letters,] III, 40. |

not the gay paradox of Wilde |

aet. 36, Dostoevsky, [Letters,] II, 275. |

Hugo, Scott & himself cf. Artistic intention. Hawthorne. Main obj. is of art. Admiration. Attitude towards realism. Pepys’ style. Personal criticism. Pepys. Burns. Charles d’Orléans.

[fol. 179] |

Stevenson. Critic. Burns. Biographical study: a portrait of a man in actions. Study of the professional Don Juan, showing a considerable knowledge of wayside love, and a keen understanding of its psychology as exemplified by Burns: due partly to impatience with an inadequate, fluid sketch by Principal Shairp, an inadequate, a ridiculously uncomprehending book which judges Burns by a very narrow standard and never attempts to define him. |

[fol. 175] |

“Stevenson. Style. Of Pepys: |

[fol. 178] |

Charles d’Orléans. 1876. His bringing in the rondel, and ballade making of Fontainebleau. Admiration for Banville: again as in Burns knack of portraiture, a little thin, a little too sure of its own comprehensiveness. Fine array of authorities. Very good copy in pen and ink of a illumination in a fine copy of the poems given by Henry VII to Elizabeth of York. His word for ‘some of our quaintly vicious contemporaries’. |

[fol. 185] |

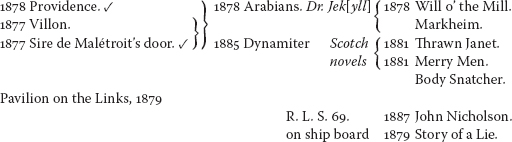

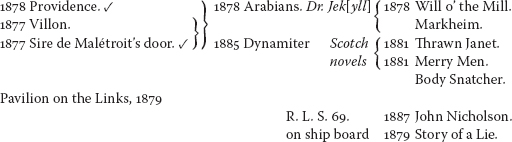

Stevenson. Short Stories. 6, 1, 3, 1½, ½ [i.e. numbers of pages written.] |

[fol. 186] |

Short Stories. |

[fol. 200] |

Tod Lapraik. Thrawn Janet, an excellent Scotch vernacular prose. ‘grandfaither’s silver tester in the puddock’s heart of him.’ Ingenious hitching with the story over to [illegible]’s quarrel. |

[fol. 234] |

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. |

[fol. 231] |

Stevenson. Fables. By 1888 most written, promised Dougram; a few added in the South Seas, published at last 1895 as appendix to new edition of J[ekyll] & Hyde. |

[fol. 261] |

Travel and Solidarity of vision. ‘I shall never do a better book than Catriona, that is my high water mark.’ Letters, IV, 258. Kidnapped, 1885. Catriona, 1893. Master of Ballantrae, 1889. A comparison with Russian literature: or Hardy. |

[fol. 289] |

Stevenson. South Seas, Oct. 25. ‘Awfully nice man here to-night. Public servant – New Zealand. Telling us all about the South Sea Islands till I was sick with desire to go there: beautiful places, green for ever; perfect climate; perfect shapes of men and women, with red flowers in their hair; and nothing to do but to study oratory and etiquette, sit in the sun, and pick up the fruits as they fall.’ June 1875, [to] Sitwell, Letters, I, 188. |

[fol. 290] |

The South Seas. The Church Builder. |

[fol. 291] |

Stevenson. The South Seas. |

[fol. 292] |

South Seas. The Church Builder. |

[fol. 330] |

[a record of pages written] |

A.2.vi Working notes for the section ‘As Happy as Kings’

[fol. 250] |

Child’s Garden. 1885. |

[fol. 251] |

‘The Shadow’ 31 ‘And in a corner find the toys |

[fol. 252] |

Child’s Garden begun at Braemar, 1880. Continued at Nice. |

[fols 253’7 are pages of quotations to support this section]

[fol. 253] |

“Stevenson: on his own verse. |

[fol. 254] |

Stevenson, of Underwoods. |

[fol. 255] |

To J. A. Symonds. Saranac, Nov. 21, 1887. [Letters,] III, 25. |

[fol. 256] |

Stevenson. Verse. |

1 ‘too willed, too conscious’ crossed out.

2 ‘esp’ crossed out.

3 ‘to keep’ crossed out.

4 ‘Weir’ > Weir of Hermiston.

5 ‘tr’ crossed out; ‘allopted’ >adopted.

6 ‘sentence quoted’ crossed out.

7 [a letter to be inserted here] > as in a letter to Henry James in 1893. [quote letter].

8 [header for this] ‘Technique of Literature. Art of Writing. 43’.

9 [fol. 134] [header] ‘Early [?]movement in words. Essays of Travel. 177.’ [fol. 135] [header] ‘Stevenson. Early Essays’.

10 [fol. 135] [header] ‘The South Seas’ crossed out. [header] ‘Essays. II’.

11 ’78 > 1878.

12 ‘still glowed’ crossed out.

13 ‘Romance’ crossed out.

14 ‘“The Amateur Emigrant”, or “New York to Sandy Hook”’ > The Amateur Emigrant from the Clyde to Sandy Hook.

15 ‘circumstances:’ > ‘circumstances.’ [then the following memorandum:] ‘Thoreau. Torojiro. Pavilion. The story of a Lie? In the ship. Plains – Prince Otto.’

16 [fol. 137] ‘Stevenson. Essays. [?‘travels’ crossed out], ‘Unpleasant Places. “Breezy. Breezy.” cf. Essays of Travel 225, with Letters I. 14.’

17 [fol. 138] ‘pays’ [mistranscription] > defrays.

18 ‘privately’ crossed out.

19 ‘Mr. Gosse (Letters, II, 177)’ > ‘Mr Gosse’.

20 ‘the’ crossed out.

21 ‘with’ crossed out.

22 ‘roars’ crossed out.

23 ‘by’ crossed out.

24 ‘becomes’ crossed out, ‘is’ superscript.