IT SHALL NOT COME NEAR YOU

On January 20, 1977, when Jimmy Carter assumed office as the thirty-ninth president of the United States, he faced the monumental task of national reconciliation after the most unpopular war in American history and the most divisive since the Civil War. At that time, the Vietnam War had been the country’s longest war, lasting from 1959 to 1975. As the first elected peacetime president afterward, his challenge to heal the nation’s wounds was paramount and daunting. Over 58,000 American soldiers had been killed in the conflict; more than 300,000 had been wounded, and some 245,000 would file for compensation for injuries they had suffered from exposure to the toxin-laced herbicide Agent Orange. These figures do not include the hundreds of thousands more who suffered from debilitating psychological wounds. More than two million Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians died during the war.

Moreover, an entire generation of young Americans that came to be known as the Vietnam Generation was said to have “dropped out.” That was especially true of the best educated. The vast majority of them had found loopholes to avoid the universal military draft. The “trick knee” became the symbol of escape, but bone spurs, marriage, graduate school, and a psychiatric diagnosis of dire mental illness were just as effective. Of the 26.8 million men of the Vietnam generation, the majority—15.4 million men—received deferments or exemptions. Only a year into the first escalation in 1966, the unease and disenchantment of the American people toward the war was already being felt. By the summer of 1968, 65 percent of those Americans polled by the Gallup organization considered the war to be a mistake. The country had definitively turned against the conflict, partly because of the high casualty rate, partly because of the graphic images of death and destruction that were conveyed nightly on television, partly through the presidential candidacies of Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy, partly because of the incessant street demonstrations by the young and vulnerable, and partly because of the shock of the Tet Offensive in January and February 1968 and the fall of Khe Sanh several months later, after the country had been reassured by its president and his generals that the war was being won. By early 1971, only 28 percent of those polled supported the war, and 72 percent favored withdrawal.

In his agenda for healing, President Carter reached out first to the young men in exile abroad in Sweden, Canada, and elsewhere. On his second day in office, he pardoned 12,800 draft evaders (deserters were not covered by the offer). Immediately, both vocal war hawks and passionate dissenters ridiculed the presidential action. By this time leaders of a well-established “amnesty movement” were arguing that to accept a pardon implied a confession of wrongdoing. What they wanted was a universal amnesty, wiping the slate clean of any criminal infraction in an act of collective amnesia. Only such a sweeping gesture would satisfy the anger of a generation faced with the impossible choice between service or flight in a bloody national endeavor that they viewed as sorely misguided. Those opposing Carter’s measure argued that to absolve draft evaders would dishonor the heroic service of those who did serve the nation when they were called. The debate would continue throughout the Carter presidency and beyond, as those in exile struggled with what they viewed as a moral dilemma. Was one to accept Carter’s pardon, accept guilt, and return home? Or stay abroad? Many stayed, smug in their moral rectitude. And those who had served, unpleasant and dangerous as their choice was, struggled to resume a semblance of normal life. That life was often conducted in a smoky netherworld of disgust and alienation and resentment.

Almost forgotten in this early period of the Carter presidency was the torment of the Vietnam veteran. More than 2.1 million men and women deployed to Vietnam over the course of the war, and returning soldiers were often scorned and humiliated as purveyors of death and torture and dupes of a discredited policy. As a veteran, having enlisted in the Army and served three years, from 1965 to 1968, I experienced this derision myself, even though I had not been to Vietnam. My college friends looked upon my service with mystification and disapproval, while they moved forward with their graduate careers or cared for their trick knees.

This identification of the American soldier with atrocity worsened after the revelation of the My Lai massacre in November 1969, twenty months after it took place. The image of blood-soaked women and children littering a ditch in that tiny village became an unforgettable snapshot of the war. My own disenchantment with the war had grown during my tour in the Army, and it grew more intense after a comrade of mine was killed, pointlessly, in Hue during the Tet Offensive.

How then should a country begin a healing process after a failed, divisive war? How was the rage and recrimination to end? How should President Carter act? How long would the process of reconstruction and reconciliation last, if indeed that healing would ever be accomplished? And what scars would endure, and how deep were they?

From 1978 to 1984, these profound questions were encapsulated in a brawl over how to commemorate that war, the first that the United States had lost. It was an extraordinary fight between groups with different attitudes toward what some called the lost cause of the twentieth century. It was also a fight between different notions about public art. It came to involve powerful forces in American politics and business, and it provoked debate over what constitutes honor and courage in times of national crisis. It prompted the question of how to thank the soldier who prosecuted the war at the same time as the protester who ultimately stopped it.

Long after the Vietnam conflict, these questions remain intensely relevant for all wars America may fight and try to end in the future.

The brawl over these issues would break out in an unusual forum: the largest competition for a public works project in the history of American or European art until that time. From this torturous battle, a work of genius emerged, and even more remarkably, that work has changed in its significance. The memorial on the National Mall is no longer just about veterans and their loss and sacrifice, no longer just about Vietnam, but about all wars and all service to country and all moral opposition to governmental authority. Its significance has profoundly changed. No one could have predicted this. It is no wonder that this simple space of contemplation remains one of the most visited of places in the nation’s capital. Even in its inscrutability, this simple V of black granite has risen to the universal.

—

The process of reconciliation after a divisive and protracted war can take years, and even longer for the losers, for the bitterness on all sides of the issue is always severe. A process of coming to terms with what actually happened and why must precede a healing, a forgiving, and a forgetting. Dealing with the American defeat in Vietnam and digesting it into the national consciousness did not really begin until about five years after the last American soldier was lifted off the roof of the American Embassy in Saigon.

The Vietnam generation—those who came of age from 1965 to 1975—could roughly be split into four groupings. There were the soldiers who were drafted or volunteered, many of whom fought in Vietnam and were then scorned by the nation when they came home. Then there were the active, passionate dissenters who fueled the protests against the war and who gathered by the hundreds of thousands beneath the Washington monument in 1969. They deserve the lion’s share of credit for eventually stopping the war. Third, there were the malingerers, who had done everything they could to avoid service and sat silently on the sidelines, smirking with contempt at both the soldiers and the protesters. As the television toggled between horrific images of bloody combat and angry demonstrations in the streets of America, politicians pitted these three groups against one another with the cynical purpose of tamping down the turmoil that roiled the nation. And finally, after a lottery began in late 1969 and the volunteer military was established in July 1973, two years before the official end of the war, there were the lucky ones who were excused with high lottery numbers or who came of age after the draft was eliminated altogether.

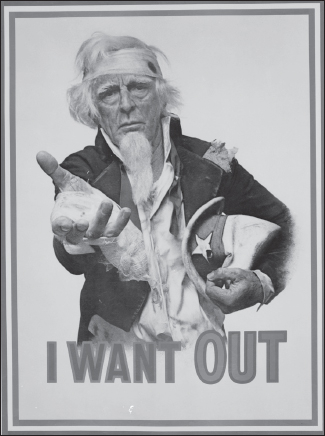

I Want Out protest poster, Committee to Help Unsell the War, 1971

The debate over the Vietnam War featured a new concept in American discourse: the immoral war. By that was meant a war that was undeclared by Congress, that was initiated under the false pretense of a nonexistent attack (such as the alleged incident that led to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution), that was based on a bogus geopolitical premise (the domino theory), and that was waged, colonialist-style, against an Asian people who possessed legitimate aspirations to be free of foreign domination. Policy makers concluded that the path to victory was the pacification of those peoples.

Well after the war was over, popular media spearheaded efforts to acknowledge what happened and why. Only with the passage of time was the wider public ready to address the profound issues of the war as presented in books, articles, and films.

There was one exception: a documentary film called Hearts and Minds (1974) that came out shortly before the last Americans fled Vietnam. Garnering an Academy Award for best documentary feature from liberal, anti-war Hollywood, it took its title from a phrase President Lyndon B. Johnson invoked multiple times as a definition of what had to happen—to “win” the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people themselves—if America was to win the war. The film had several indelible interchanges. In one, General George Patton, Jr., son of the World War II hero, was shown at a funeral of several war victims, when he turned to the camera and said soberly, “They’re reverent, determined, a bloody good bunch of killers.” The second was even more revealing. The supreme commander of American forces, General William Westmoreland, remarked, “The Oriental doesn’t put the same price on life, as does the Westerner. Life is plentiful there. Life is cheap in the Orient.” But the timing was too early for the film to have a lasting effect on the reconciliation process.

Toward the end of the 1970s the psychological toll on soldiers who had been in Vietnam rose to the surface as a major issue, taking its place alongside the enormous casualty rate. It gradually became clear that hundreds of thousands of surviving veterans were suffering from severe psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, alcoholism, and insomnia, not to mention thoughts of suicide. This was, of course, not a new issue. After World War I, Virginia Woolf defined the problem best through the main character of her novel, Mrs. Dalloway. Septimus had been a brave warrior, but after the war he descended into an abyss of desolation. “Now that it was all over, truce signed, and the dead buried, he had, especially in the evening, these sudden thunderclaps of fear. He could not feel.” He had expended all his bravery on the battlefield, Woolf imagined, and could not relate either to his fellow man or to postwar England. Dating back well beyond World War I to ancient Greece and Rome, the issue transcends Vietnam. The veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan know this all too well. Only in the late 1970s was this mental disorder given a new, medical diagnosis: post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

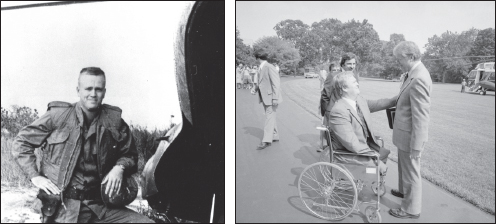

On the official side, President Carter’s administrator of Veterans Affairs, Max Cleland, led a campaign for “readjustment” therapy with a modest proposal to Congress to fund treatment counselors around the country to deal with servicemen’s psychological problems. Cleland himself is an amazing case. A captain in the First Cavalry Division who joined the army for the most noble of reasons, he had experienced the Tet Offensive and then volunteered for the perilous mission to relieve the siege of Khe Sanh. But on the day the siege was finally lifted, April 8, 1968, after three months of “total war,” Cleland was horribly wounded by friendly fire. A grenade exploded immediately behind him as a fellow trooper carelessly handled his weapons. Cleland lost two legs and an arm.

As a triple amputee, he spoke with great authority and feeling in support of a modest allotment to counsel returning soldiers for drug and alcohol addiction. He likened coming back to civilian life to the explosions that often followed an airstrike in combat. “Coming home [was like] a series of secondary explosions, where the Vietnam veteran is left alone with his pain and his agony, to try to explain it by himself. That was one reason why we needed the support of psychological counseling in the Veterans Administration which had never been done before unless you’re psycho.”

Max Cleland in Vietnam, circa 1966 (left) and with President Jimmy Carter at the White House, July 28, 1978

After 1971, Congress repeatedly rejected proposals for veterans’ counseling services. As VA administrator, Cleland pleaded for a mere $10 million to start a nationwide network of three hundred counselors. At the time, there were only nineteen Vietnam-era veterans in Congress, whereas in 1946, sixty-nine World War II veterans were elected to Congress. But with dogged persistence Cleland finally carried the day, and on June 13, 1979, Public Law 96–22 finally passed.

Coupled with the awareness of widespread mental disease among returning veterans was the discovery of the physical damage that the toxic defoliant known as Agent Orange had done to the thousands who had come into contact with it. In GI Guinea Pigs (1980), authors Todd Ensign and Vietnam veteran Mike Uhl chronicled the wanton disregard for soldiers’ well-being that the broadcasting of this poison throughout Vietnam had caused for the soldier on the ground.

Each side in the debate over the war had their heroes and their villains. For the hawks, the icon was John Wayne in the 1968 film The Green Berets. For the war protesters, there were the songs of Joan Baez and the brazen actions of Father Daniel Berrigan and others. The symbols of this dissent were the unforgettable images of the massacre at My Lai, the murder of four students at Kent State University during an anti-war protest, the naked Vietnamese girl fleeing the fire of American napalm, the last helicopter to lift off from the roof of a Saigon apartment house, flower-wielding protesters confronting soldiers with fixed bayonets at the Pentagon, and a Vietnamese police chief assassinating a Viet Cong soldier.

The most incendiary figure of the anti-war movement was actress Jane Fonda. She would later say that her anger over Vietnam began after seeing US carpet bombing on French television when she lived in Paris with her first husband, Roger Vadim. Between 1970 and 1972, while the war was still raging, she barnstormed the country on an anti-war road show and lecture tour. She then famously traveled to North Vietnam and visited with American POWs. John McCain, the navy flyer and later US senator, who was held in the infamous Hanoi Hilton, refused to see her, saying later that he did not think she would be a very good emissary of the truth back home. During this provocative two-week visit to the enemy’s lair, she made broadcasts on Hanoi radio, denounced the bombing of Hanoi’s dikes, and blasted American war policy in general, earning her the label “Hanoi Jane.” She also allowed herself to be photographed next to a North Vietnamese anti-aircraft gun. In later years that photograph was the only aspect of her anti-war campaigning that she came to regret. For many, her behavior qualified as bald-faced treason for giving aid and comfort to the enemy.

Meanwhile, in early 1972, as she was divorcing Vadim, she collected her first Oscar as best actress for her performance in Klute. She wore a black Maoist pantsuit—itself a provocative statement—to the ceremony, and Academy Award officials cringed at the possibility that she might use the platform to rant about Vietnam.

“I wanted to make a speech about Vietnam,” she said later, but her father, Henry Fonda, counseled against it. “He said to me: ‘Just say: There is a lot to be said. But tonight is not the time.’”

Counterintuitively, Fonda developed and starred in Coming Home (1978), a moving film about returning veterans. Contrary to her harsh reputation in real life, Fonda’s character, Sally, is shy, torn by divided loyalties, and married to a hard-bitten Marine (Bruce Dern). But after her husband goes off to Vietnam, she falls in love with a war-scarred paraplegic (Jon Voigt) in a veterans’ hospital. The movie did a great deal to refocus public attention on the war wounded, both physical and psychological. Despite Fonda having conceived the film and gotten it made, the movie did not change her reputation as an inflammatory symbol that hawks and many veterans would resent for decades to come.

Another powerful and tragic movie, released in late 1978, reflected the shifting mood of the American public toward the war. The Deer Hunter is the story of three Russian-American steel workers from Pennsylvania who live in grimy houses, labor near the cauldrons of molten steel in the smoky factories, and who play and dance with tremendous gusto, especially with Linda (Meryl Streep) before they go off to experience horrific combat and imprisonment in Vietnam. “Do you think we’ll ever come back?” one of them asks another. Only the lead character, Michael (Robert de Niro), outlives the horrors, while one buddy, Nick (Christopher Walken), survives the war only to kill himself during a game of Russian roulette. The third (John Savage) ends up a paraplegic after being badly wounded in an escape from a barbarous Viet Cong prison. Michael is the only one strong enough to bear the numbing dislocation of returning home.

The movie was received as a relentless indictment of a war that had destroyed lives in a purposeless endeavor. Yet the characters themselves try to hold on to their love of country even as they are disconnected and aimless in their return. The film ends with a gathering after Nick’s funeral, as the victims sing “God Bless America” quietly and sadly. An editorial in the Washington Post observed that The Deer Hunter “depoliticizes the war almost entirely, exchanging considerations of historical rightness for strictly human concerns. Depoliticization is what you do to a war you haven’t won. It makes its memory easier to take.”

“The evidence of these two movies,” wrote commentator Stephen S. Rosenfeld, “is that we are halfway, but only halfway, home from the war.”

In the literary world three strong voices emerged to challenge conventional wisdom. The first belonged to Tim O’Brien, whose novel, Going After Cacciato, caused a stir when it was published in 1978. (In Italian cacciato means “hunted.”) The story is about a soldier who goes absent without leave to walk from Vietnam to Paris and the men who went after him. To endure the endless slog of war, the protagonist deludes himself. “Waiting, trying to imagine a rightful but still happy ending, Paul Berlin found himself pretending, in a wishful soft way, that before long the war would reach a climax beyond which everything else would seem bland and commonplace. A point at which he could stop being afraid. Where all the bad things, the painful and grotesque and ugly things, would give way to something better. He pretended he had crossed the threshold.” The novel received the National Book Award for Fiction in 1978.

Philip Caputo’s book, A Rumor of War (1977), had a different take. It is a classic war memoir that chronicles Caputo’s searing experience as a Marine lieutenant in Vietnam in 1965–66. He had arrived in-country as a twenty-four-year-old romantic, a literature major in college, entranced by the novels of Rudyard Kipling and Saul Bellow and the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Dylan Thomas. He was an adventurer for whom war had seemed like the ultimate “chance to live heroically.” He arrived in Vietnam with swagger and idealism. But after his first blistering summer in the combat zone, he aged, technically, three months, “but emotionally about three decades.” In the fierce fights for one forgettable numbered hill after another, in watching his unit depleted from 175 to 95 men in one four-month period, and in rebelling against his superiors’ obsession with body counts, he chronicles his descent into disillusionment. Caputo is appalled when his fellow soldiers go berserk. Of all the ugly sights in Vietnam, he wrote, the ugliest was seeing that “the change in us, from disciplined soldiers to unrestrained savages and back to soldiers, had been so swift and profound as to lend a dreamlike quality to the last part of the battle.” The book ends with his humiliating court-martial for allegedly encouraging the assassination of a Vietnamese informant in a case of mistaken identity. After seventeen months in Vietnam, having witnessed unspeakable carnage, Caputo survived without a scratch, but he emerged as a “moral casualty.” The book was later made into a television mini-series.

Finally, there was Michael Herr’s Dispatches (1977). It is a compilation of a few long pieces he had written as a journalist for several leading magazines. Adopting a stream-of-consciousness style and writing primarily from the viewpoint of the grunts in the field, Herr delivered a tour-de-force portrayal of the combat soldier and the landscape of battle. Herr’s writing is beautiful and intimate, empathetic and terrifying, especially in its treatment of the siege of Khe Sanh, America’s version of the French debacle at Dien Bien Phu, in the winter of 1968. “All that anyone could see of the hills had been what little the transient mists allowed,” he wrote of Khe Sanh’s surroundings, “a desolated terrain, cold, hostile, all colors deadened by the rainless monsoon or secreted in the fog. … Mostly, I think, the Marines hated those hills; not from time to time, but constantly, like a curse. … I heard a grunt call them ‘angry,’ … So when we decimated them, broke them, burned parts of them so that nothing would ever live on them again, it must have given a lot of Marines a good feeling, an intimation of power.” And Herr is brilliant in locating what Virginia Woolf called the “creative fact or the fertile fact,” the fact that elucidates character. Once he finds himself seated next to a Marine in a helicopter ride from Cam Lo to Dong Ha. The soldier is overweight, but “you could see from his boots and his fatigues that he’d humped it a lot over there.” The Marine pulls out a Bible, leafs to Psalm 91:5, and shows it to Herr:

Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night; nor for the arrow that flieth by day.

Nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness; nor for the destruction that wasteth at noonday.

A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand;

but it shall not come nigh thee.

Amid the noise of the chopper Herr scribbled “beautiful” on a piece of paper and handed it to the Marine. But later he would write that he was thinking to himself of a counter verse, Psalm 106:39:

Thus were they defiled with their own works

And went a-whoring with their own inventions.

It was these works—and even soldiers’ poems—that did so much to drive a cultural shift in the late 1970s. A time of gestation was needed for the country to absorb the defeat and come to terms with it. Such powerful, intimate, and emotional works that made the experience of the soldier real and immediate did far more to move the nation than the words of politicians and activists.

One noteworthy poem was written by Lewis Bruchey, who had performed perhaps the most dangerous mission any soldier could endure in Vietnam. As the leader of a five-man Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol for the Army Rangers, his job was to roam far from his unit in lonely scouting missions searching for the elusive enemy. He was later awarded the Silver and Bronze Stars for bravery. The awards, he said wryly, were for “staying alive for a year, I guess.” His poem, “Cold, Stone Man,” includes these lines:

They pin

A star

Upon my chest,

A subtle nod,

Alone

I stand.

I AM THE BEST.

But wait.

Remember

The rockets,

The jungle,

The rain?

Remember

Evil, masked

In pain?

Remember

Night sounds

Eyes strain’d

To see?

Remember

Death stalking

The darkness,

A reaper

To reap me?

I do! I do!

So speak softly

To me,

And do not

Stare.

Your sorrow,

Your pity,

Your prayer.

For I am

A cold, stone man

Of Vietnam.

Beware! Beware!