REMEMBER US

Jimmy Carter finally turned to the anguish of the Vietnam veteran late in his presidency. On Wednesday, May 30, 1979, at a White House reception for veterans after the Memorial Day holiday, the president proclaimed that the nation was, at last, ready to change its heart and mind toward the Vietnam soldier and recognize his valor, sacrifice, and commitment. For the melody of the moment, he drew on Philip Caputo’s book and the author’s moving tribute to a fallen comrade:

“You were part of us, and a part of us died with you, the small part that was still young …. Your courage was an example to us, and whatever the rights or wrongs of the war, nothing can diminish the rightness of what you tried to do. Yours was the greater love.”

The president’s focus had been nearly a year in coming, and Jan Scruggs, a shy, somewhat awkward twenty-nine-year-old veteran, deserved much of the credit. As a teenage member of the 199th Light Infantry Brigade, Scruggs had been badly wounded by a rocket-propelled grenade in a bloody battle northeast of Saigon in May 1969. In the time he spent in a hospital in Cam Ranh Bay recovering, he came to accept his injury without bitterness but as a predictable event of war. He had earned his “red badge of courage,” he would say. Two months later he returned to duty. Then in January 1970 he saw twelve of his comrades pulverized when an ammunition truck exploded. “That’s what gave me PTSD,” he would say later. Over the course of his tour, he had seen half of his company killed or wounded.

Meeting at the US Capitol, December 1979. From left to right: Senator Mack Mathias, Senator Robert Dole, Jan Scruggs, Tom Carhart, Senator Dale Bumpers, and Robert Doubek

Back home he graduated from American University in 1975 and went on to earn a master’s degree in psychology a year later, focusing on Vietnam veterans’ painful readjustment to civilian life and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), from which he himself suffered. In May 1977, he penned an article for the Washington Post entitled “Forgotten Veterans of that ‘Peculiar War.’” “Perhaps a national monument is in order to remind an ungrateful nation of what it has done to its sons,” he wrote. Fifteen months later he published his second bitter editorial about the “continued indifference” toward the Vietnam veteran. He had come to believe that something more than hypocritical political rhetoric was needed to honor soldiers like himself who had answered the country’s call.

Scruggs’s notion of a national memorial for Vietnam veterans was percolating. And he was channeling Carl Jung’s concept of “collective unconscious,” which he had encountered in his psychology classes. Jung argues that all humans share certain fundamental values, one of which is the deep appreciation for those who give their lives for others. And Jung’s definition of the archetypical hero—one who overcomes immense obstacles, achieves extraordinary goals, and transcends inner darkness—also captivated him. From these Jungian notions, Scruggs imagined a memorial of names. The names of the fallen on a memorial, he felt, would guarantee overwhelming public and political support. Ultimately, however, it was seeing The Deer Hunter in early 1979 that galvanized him, solidifying his idea of building a memorial to his fellow soldiers and realizing that, if it was to happen, he would have to lead the effort himself. As he remembered later, “I was thinking things over and I got very depressed. I started getting flashbacks, it was just like I was in the Army again and I saw my buddies dead there, twelve guys, their brains and intestines all over the place, twelve guys in a pile where mortar rounds had come in.”

A month later the movies again had an impact on public awareness when 64 million viewers watched a television program entitled Friendly Fire about a mother in rural Iowa, fighting against government obfuscation to find the truth about her son’s death from soldiers on his own side. Starring Carol Burnett, Ned Beatty, and Sam Waterston, the movie is based on a 1976 book of the same title by C. D. B. Bryan.

That spring, with $2,800 of his own money and being somewhat clueless about the immense hurdles he would be facing, Scruggs began to mobilize a campaign for a memorial that would honor the poignant sacrifices of US servicemen in Vietnam. He imagined such a memorial in a prominent place on the National Mall in Washington, DC, with a garden-like setting where visitors would come for rest and reflection. He hoped as well that there might be some sort of a realistic sculpture of the Vietnam soldier. In late April, Scruggs and friends formed a corporation called the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF). They held a press conference over Memorial Day weekend and boldly announced their intent to raise one million dollars to build their memorial.

But the effort got off to a rocky start. In June, Roger Mudd of CBS News reported that the group had raised exactly $144.50. Shortly afterwards, their efforts were spoofed on late night television.

Then there was the matter of the creation and its execution: who could design and build such a memorial? Scruggs thought he knew the very people who could provide just the right combination of setting and art: Joseph E. Brown, a prominent landscape architect who was already engaged in designing a park and pond on the Mall to honor the fifty-six signers of the Declaration of Independence and Frederick Hart, a brilliant young artist who was then working on a sculpture for the main entrance of the Washington National Cathedral. That early relationship with Scruggs and company gave Brown and Hart an inside track to be chosen for creating and building the memorial, should the project go forward.

But Hart would have the misfortune of attending an elegant dinner party on July 29 at the home of Wolf Von Eckardt, the art and architecture critic for the Washington Post. Von Eckardt was already a big fan of Hart’s: he had written glowingly about the sculptor’s classical works at the cathedral. Also present at the soiree was the critic’s friend and colleague, Judith Martin, the future etiquette advice columnist known as Miss Manners, who was then a drama and film critic at the Post. To the surprise of all, Hart announced, with a certain pride and humility, that he had been chosen to provide the sculpture for the Vietnam Memorial. Von Eckardt rose up in a passionate outburst, voicing strong objection. Martin thought her friend might leap across the table with a knife. This memorial was far too huge and important, Von Eckardt fumed. How could Scruggs and company blithely award such an important prize to their favorite sculptor, no matter how nice and talented that artist might be? There had to be a national competition, Von Eckardt insisted, and he, by golly, would see to it that it happened.

The idea of design competitions for public art has a long and storied tradition in America. After George Washington’s death, a number of proposals surfaced for honoring the first president. The first attempt was Horatio Greenough’s sculpture of Washington as a seated and half-naked Roman hero draped with a toga. His statue was received with universal scorn. Meanwhile, a memorial commission of prominent Washingtonians was formed with Chief Justice John Marshall as the honorary chairman. Subsequently, artists presented designs from Greek, Roman, Renaissance, and Mayan traditions. The winning design by Robert Mills called for a five-hundred-foot Egyptian obelisk whose base was a pantheon of thirty columns and whose top featured Washington in a horse-drawn chariot. Construction began in 1848, but the Civil War interrupted the work, leaving the obelisk at 150 feet, well short of its planned height. After the war, Mark Twain described the unfinished stump as “a factory chimney with top broken off [and] cow sheds around its base, and the contented sheep nibbling pebbles in the desert solitudes that surround it, and the tired pigs dozing in the holy calm of its protecting shadow.” Not until 1884, through the intercession of many architects and politicians, was the Mills design modified to its current, simple pyramid finish with all the embellishments scrapped. Upon its completion critics again lambasted it, but the public quickly embraced its spare, simple elegance.

A century later the protracted and troubled campaign to craft a memorial in Washington for Franklin Roosevelt met with disappointing results. For that design competition Congress established an advisory committee in 1955 that was to include such luminaries as historian Lewis Mumford, Pietro Belluschi, the dean of architecture at MIT, and Hideo Sasaki, head of the Harvard School of Design. Even with such a distinguished panel, the initial efforts for an FDR monument woefully failed, when the winning design was contemptuously dubbed “instant Stonehenge” and then discarded. Lewis Mumford provided the dirge: “The notion of a modern monument is veritably a contradiction in terms. If it is a monument, it is not modern, and if it is modern, it cannot be a monument.”

It was not until 1978 that a design was finally approved; another nineteen years would pass before FDR’s memorial opened to the public on the Tidal Basin near the Jefferson Memorial.

Nevertheless, the failure of the FDR effort notwithstanding, Von Eckardt argued forcefully that something similar should be organized for this memorial. Eventually, he calmed down and became again the good host that he was. All congratulated Hart on his good fortune.

In a subsequent column in the Washington Post, Von Eckardt stated his case. He cited a few memorials around the world that moved him: the Fosse Ardeatine in Rome that holds the graves of Italian villagers murdered by the Nazis, the Ossip Zadkine sculpture in Rotterdam called simply May 1940, the month that the Luftwaffe destroyed that city, and the Hall of Remembrance in Jerusalem that inscribes in stone twenty-one of the largest Nazi death camps.

“None of these … is ‘good art’ or popular art, abstract or representational, ‘modern’ or ‘traditional,’” Von Eckardt wrote. “They are simply powerful ideas translated into a powerful emotional experience. And that is what I think the Vietnam Veterans Memorial group needs. To elicit powerful ideas, there must be a competition. It would be corrupt for some more or less self-appointed committee to pick some favorite.” He did not mention Hart by name. The critic would have his way. And Frederick Hart would feel as if the prize had been snatched away from him.

In August, the group got its first political breakthrough when Senator Mack Mathias of Maryland contacted the organizers and offered help. In the year that followed, a bill to erect some sort of a Vietnam memorial began to make its way through Congress. Senator John Warner of Virginia joined Mathias, and together they spearheaded the congressional effort. But central to the plan was the Congressional requirement that funds for the memorial be privately raised. Early in 1980 VVMF sent out two hundred thousand fundraising letters for the cause, and later, on Memorial Day, they sent out a million more. A disparate group of celebrities lent themselves to the effort, including Jimmy Stewart and Bob Hope. The money began to pour in. Scruggs became the face of the endeavor, and he proved himself to be an adept promoter.

In November 1979, he wrote a powerful op-ed piece in the Washington Post, railing against the media’s portrayal of Vietnam veterans as “violence-prone, psychological basket cases.” Such a characterization was, he wrote, “collective character assassination.” The title of his piece was “We were young. We have died. Remember us,” a line borrowed from Archibald MacLeish’s poem “The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak,” which the poet had written when he was Librarian of Congress during World War II. The poem, often etched on war memorials, reads in part:

They say, We have done what we could but until it is

finished, it is not done.

They say, We have given our lives but until it is

finished no one can know what our lives gave.

They say, Our deaths are not ours: they are yours:

they will mean what you make of them …

They say, We leave you our deaths: give them their

meaning: give them an end to the war and a true peace: give

them a victory that ends the war and a peace afterwards: give

them their meaning.

We were young, they say. We have died. Remember us.

Tom Chorlton, a dissident who had spent six years protesting against the war, responded to Scruggs’s piece.

“If this memorial is to serve any positive purpose, however, it must include those who also suffered by recognizing the tragedy of this war and therefore resisted the draft. … I must resist any attempt to apologize to those who served in the military by white-washing the realities of that brave struggle. … We must make absolutely clear to ourselves and to history that we are not honoring the Vietnam War itself. At the very least, this memorial must include all war resisters who were imprisoned for resisting the draft. This is the minimum, the very least that must be demanded by the tens of thousands of us who also suffered by trying to bring our country to its senses.”

No one was listening.

—

As the push behind the idea of a memorial grew stronger, Scruggs was shown a number of possible sites for his tribute. The guardians of Washington’s public spaces were stingy in ceding ground in central Washington. The US Commission on Fine Arts suggested space near the Arlington Cemetery. But the organizers were not disposed to accept some small, out-of-the way niche. To hide the memorial was to sideline the war, as if it was something to be ashamed of. Scruggs had his eye on something far more prominent: a corner of the National Mall itself, a two-and-one-half acre plot of rolling ground just northeast of the shrine to Abraham Lincoln. On its face, this was an outrageous proposition. There was still no World War II memorial in Washington to honor the sixteen million Americans who served and the four hundred thousand who were killed. And there was no national monument in the nation’s capital to commemorate the 116,000 Americans who died in World War I. But Scruggs was very persistent.

For decades “temporary” military structures set up during World War I had occupied the area. With the American bicentennial celebration in 1976, the cleared area was set aside as a pastoral place of reflection and eight years later became a tribute, known as Constitution Gardens, to the founding fathers. The resistance to any further “improvement” was great among the city’s planners, who believed that this portion of the Mall should remain a quiet byway of planted trees, serene waters, and twisting pathways somewhat like the Bois de Boulogne in Paris. During his presidency, Richard Nixon had noticed the area’s pristine emptiness on one of his helicopter rides off the White House lawn and seized on the idea that this would be a perfect spot for an amusement park along the lines of Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, replete with a carousel, bandstand, puppet shows, jugglers, and café. Fortunately, as the Watergate scandal came to dominate Nixon’s attention, this proposal, like Nixon, languished.

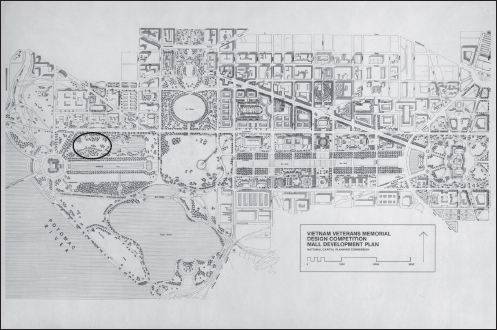

Plan of the National Mall, Washington, DC, circa 1980, with the projected site for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial indicated on the left.

Ultimately, Senator Mathias and twenty-five cosponsors introduced a bill specifying Constitution Gardens as the site for a Vietnam War memorial. As Memorial Day of 1980 approached, it passed unanimously in the US Senate and sailed easily through the House of Representatives.

The critical government agency to approve or reject the project was the National Commission on Fine Arts. Immediately, the commission chairman, J. Carter Brown, voiced strong objection to the designated site. “It is the commission’s belief that if Constitution Gardens should become the setting for major memorials … the intended character of the park will be seriously diminished, if not lost altogether.” This objection created a momentary hiccup in the process. But patriotic fervor always trumps artistic quibbles. This would be the first of many instances in this saga in which political forces would override artistic considerations. The objections were ignored.

On July 1, 1980, President Carter signed the bill into law. In celebrating its passage, the president returned to the words of Philip Caputo. This time, however, he quoted a Caputo passage he had omitted a year earlier. In the continuation of Caputo’s letter to his fallen comrade, the author mourned that the country had not matched the faithfulness of his friend. There were no monuments or memorials, no statues, or plaques, the author insisted, because such symbols would make Vietnam harder to forget.

Now, at last, that would change. There would be a remembrance, if the right artistic concept could be found that would pass the muster of the Washington salons, and if the money for its construction could be raised. When the ground in Constitutional Gardens was finally consecrated, after the strains of the Battle Hymn of the Republic echoed to the Lincoln Memorial, a clergyman delivered the hopeful invocation.

“For those who yet suffer wounds, for those not yet home, let this be a mecca for healing.” Some saw this as equivalent to tears as well as joy at a wedding, appreciating what trials lay ahead.

For more than a year the VVMF had toiled on in the thankless task of soliciting donations for an abstract idea. Things had started slowly, but there were a few early successes. Most significant was a call Jan Scruggs made to the Texas billionaire Ross Perot. A proud navy veteran, Perot was one of the greatest fast-talking salesmen in America. His data collection company, Electronic Data Systems (EDS), had had a stratospheric rise into the top ranks of American business, fueled by fat government contracts and deals with corporate giants such as General Motors. He was also passionately involved in POW/MIA issues, partly because his roommate at the US Naval Academy had been killed in Vietnam. In 1979, he achieved considerable publicity after several of his EDS employees were taken hostage in Iran, then in the throes of the Ayatollah Khomeini revolution.

To rescue his employees, Perot had recruited a band of seasoned warriors, led by a notorious ex-Green Beret colonel, Arthur “Bull” Simons. In 1970, Simons led a perilous mission into North Vietnam to free Americans, including a navy fighter pilot named John McCain, from a prison at Son Tay. The mission failed, but it forced the North Vietnamese to consolidate American captives in a prison at Hòa Lo in central Hanoi. That prison would be dubbed the “Hanoi Hilton.” In the Iran operation, the Simons team melted into a huge pro-Khomeini rally and freed the EDS employees as well as a large number of political prisoners. Simons then successfully spirited them out of the country to safety.

So, Perot, now among the richest men in America and an acknowledged super-patriot, was a good target for a donation. Scruggs’s first call to him netted a cool $10,000.

Another success came at the hands of Scruggs’s most important political connection, Senator John Warner. In December 1979 Warner hosted a breakfast with thirteen corporate executives at his tony Georgetown mansion across from Dumbarton Oaks. He would later claim that when his wife, Elizabeth Taylor—he was her sixth husband—made a grand entrance in a pink bath robe with dangling fluffy white balls and pink slippers, the businessmen tripled their donations.

Warner and Taylor had a much more public encore ten months later when they hosted a black-tie extravaganza at the old Pension Building in downtown Washington. Warner looked grand in his tuxedo with the medals he earned as an ensign in World War II and as a marine in the Korean War prominently on display over his left lapel. Besides Senators Warner and Mathias and a number of crusty veterans, the headliners for this event included Perot, General William Westmoreland, Veterans Affairs administrator, Max Cleland, twenty-five generals and admirals, and a handful of corporate chairmen from such firms as General Electric and General Dynamics. Perot, gabby as ever, gave a breezy rendition of his now-famous Iran rescue operation and told of how he had insisted that his commandos be Vietnam veterans. “You take these young guys out and give ’em a mission and cut out all the chatter and they do just fine,” he told a reporter.

Elizabeth Taylor looked pretty good too that night in a blousy red dress with Greek designs that the Washington Post described as “flimsy.” In the estimation of some, the actress did not really look like she wanted to be at the gala, as if she had been trotted out for show against her will. Perhaps as a result, she displayed a flash of her famous temper. When she passed a table and a brash veteran shouted out, “Hey, Miss Taylor, can I take your picture?” Taylor turned on him with a fiery look and said, “It’s Mrs. Warner, chump,” whereupon the veteran’s wife, a tough-looking, no-nonsense woman, jumped up to defend her man, and the two started jawing at one another. The muscle was called in to break up the fight.

There would be other awkward moments. General Westmoreland looked very much the marble man as he assumed the podium. When he began to spout the usual stuff about honor, duty, and country, a veteran in a wheelchair whispered to his dinner partner that he thought Westmoreland was “out of his fucking mind. If they’d given him what he wanted over there, he would have blown the hell out of everything.” And even Scruggs, whom the audience might have assumed to be an uncritical flag-waver, gave voice to inner conflict. The author of the memorial to honor soldiers perfectly represented the overwhelmingly anti-war sentiments of most Vietnam veterans and indeed the inner conflict of the entire Vietnam generation.

“I basically think that the war was a serious mistake,” he told a reporter. “I’m not pro-war, and not a right-wing warrior. … I later protested against the war. I gotta admit I’m still quite confused about the damn thing.”

So, it was left to a stocky ex-Marine with curly red hair to express an unqualified love of country. “The key thing that’s been missing is simply according to the people who served, the dignity of their experience,” he said. “The hardest reentry point for Vietnam guys was their own peer group.” His name was James Webb. By this time, he was best known for his gritty Vietnam novel, Fields of Fire (1978), which had sold more than seven hundred thousand copies. Webb had convinced his publisher to provide several hundred copies of his book as party favors at the gala, and he was on the VVMF’s advisory committee.

All the same, for all the fun and folderol the event at the Pension Building grossed $85,000 for the Memorial Fund. By mid-March 1981, the patrons had $820,000. Then at the end of April, only days before the winner of the grand design contest was announced, Perot stepped forward with an additional $160,000 to underpin the entire cost of the competition.