NOTHING TO ADD, NOTHING TO TAKE AWAY

In 1980, the campus of Yale University had settled into a malaise of relative quiet after an era of turbulence over civil rights and the Vietnam War. Students had turned their gaze inward to their courses and their grades. Indifferent toward national and international concerns, their minds and hopes were fixed on their future careers. The Vietnam War was now a distant memory. The draft had been scrapped seven years earlier as the volunteer army had relieved every young male of concern over conscription. Apart from the revolutionary regime of the Ayatollah Khomeini that had taken American hostages in Iran and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the world was experiencing a comparative lull from large-scale bloody conflict. Ronald Reagan had been elected that fall in a landslide and Mount St. Helens had blown its top in Oregon. But among the top news stories that year, students on campus were inclined to be most upset over the assassination of John Lennon.

A decidedly cynical view of the world had replaced outrage. It was easy to hear complaints about America’s militaristic tendencies, though none were then in force. The Watergate scandal held more sway over the minds of Yale students than Vietnam, and it encouraged the view that all politicians were essentially corrupt. Public service was not respectable. If the subject of America’s most unpopular war arose—a war that had ended when these students were young adolescents—the protesters against it were generally seen as long-haired, drug-happy hippies. The fall semester began with a well-attended lecture by Barry Commoner, the famous biologist and founder of the modern environmental movement who was then running for president as a candidate for something called the Citizens Party. The students applauded when Commoner suggested resuming diplomatic relations with Iran.

If the students at Yale were mostly indifferent to national and international issues, the same could not be said of the faculty. A large proportion of them had been very active in the anti-war movement in the 1960s and early 1970s. That was especially true from 1967 to 1969, when more than forty thousand American soldiers were killed. Protest in the country at large against the war rose in concert with this horrendous casualty rate, climaxing with the march of a hundred thousand protesters at the Pentagon in 1967 and an even larger demonstration at the Washington Monument in 1969.

Most prominent among the activists on the Yale campus was Reverend William Sloan Coffin, Jr., the mesmerizing university chaplain and one of the most visible and charismatic leaders of the anti-war protest. A great teddy-bear of a man, full of good humor and fun and much beloved by students for his bombast and principles as well as for his booming singing voice and raucous piano playing, he had proposed in 1967 to make Battell Chapel a sanctuary for fugitive draft evaders. In 1970, activist students sought to bar a US Marine Corps recruiter from Yale, and in May Day protests of that year they went on strike, shutting down the campus with a complete cessation of classes (although no buildings were occupied, unlike at Harvard and Columbia). National Guard troops deployed to New Haven and downtown shops closed and were boarded up as fifteen thousand people gathered on the town green. The following Monday, May 4, Ohio National Guard soldiers opened fire on war protesters at Kent State University, killing four, only two of whom were demonstrating.

In that same year, a federal grand jury indicted Coffin for abetting draft resistance. Though he was convicted, an appeals court eventually overturned the verdict. Coffin left Yale in 1977 to become the senior pastor at the Riverside Church in New York, and thus the university lost a mobilizing force.

In 1970 Vietnam and civil rights were joined in an incendiary mix as New Haven became the rallying point for black militancy. The town was the setting for the trial of Bobby Seale, a co-founder of the Black Panther party. Seale was already famous as one of the original “Chicago Seven,” the group charged with violently disrupting the 1968 Democratic Convention in a protest over the Vietnam War. At their trial, Seale engaged in constant outbursts against the proceedings, and, as a result, was gagged and bound to his chair. This incident inspired a popular protest song by Crosby, Stills, and Nash called “Chicago,” which included the lyrics, “So your brother’s bound and gagged, and they’ve chained him to a chair.” For his interruptions, Seale was sentenced to four years in prison for contempt of court.

Before he was incarcerated, however, the Panther leader spoke at a raucous gathering on the Yale campus. Later that night, Alex Rackley, an alleged informer within the Panther ranks, was murdered, and Seale was said to have ordered the killing. The Panther among the “Chicago Seven” now became the principal in a trial of the “New Haven Eight.” The evidence against him was slim, and protesters denounced the trial as a travesty. The case against Seale was ultimately dismissed, but not before Reverend Coffin stepped forward to castigate the process and underscore the moral imperative of personal witness: “All of us conspired to bring on this tragedy—law enforcement agencies by their illegal acts against the Panthers,” he said, “and the rest of us by our immoral silence in the face of these acts.” Yale’s president, Kingman Brewster, Jr., joined in Coffin’s denunciation, doubting that black revolutionaries could receive a fair trial anywhere in the United States.

In 1977, there was a brief flurry of activism at Yale, when food service workers on campus went on strike. Activists took sides, but most students, including a quiet, scholarly Asian-American sophomore from Ohio, were merely annoyed by the disturbance and inconvenience of the strike.

Given the changed circumstances of the time, the protest and pacifism that had once been in the life-blood of Yale did not run through the veins of the Class of 1981.

—

In the summer of 1980, Andrus Burr, a junior architecture professor at Yale, had spent his vacation in Europe looking at famous cemeteries. For a slight man with an unfailingly sunny disposition, this might seem like a depressing way to spend a holiday. But Burr was fascinated by the way human beings over the centuries memorialized their dead and how certain tombs and burial grounds can uplift the spirit. In Paris, he meandered through the famous Père Lachaise cemetery, not only for the elaborate tombs of its famous residents, including Chopin, Balzac, Molière, and Proust, but because the burial ground seemed to him collectively like a “city of the dead.” He made a note to himself that there was nothing quite as grand as this in America, except perhaps the Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn. Burr tarried at the bizarre tomb of Jim Morrison, the charismatic singer-songwriter of The Doors, whose bust, just above ground, made it look as if he had been buried from the neck down. He missed the tomb of Oscar Wilde with its inscription from the Irishman’s famous poem, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol.”

And alien tears will fill for him

Pity’s long-broken urn

For his mourners will be outcast men

And outcasts always mourn.

But there was no missing the amazing sculptural and architectural piece by Bartholomé at the end of the entrance boulevard with its inscription, Upon those who dwelt in the land of the shadow of the dead, a light has dawned.

After Paris, Professor Burr concentrated on war memorials. Among the many cemeteries he would visit that summer was the overpowering Thiepval Memorial in Sommes, France, which commemorates some 72,000 soldiers killed in the unimaginable battlefield slaughters there from 1916 to 1918. Amid the ocean of simple white gravestones a gargantuan, monumental cenotaph with intersecting triumphal arches, designed by the great British architect Sir Edwin Lutyens, presides over the assemblage. Burr would note that there was no image of the human figure. And at Étaples, also appointed with a Lutyens structure, Burr marveled at the commemoration of the military hospitals that were located there and where more than ten thousand war dead are buried.

This tour paid dividends when Burr returned to Yale. His dean, César Pelli (later the architect of some of the world’s tallest skyscrapers), determined that the department of architecture needed another course. Burr suggested “funerary architecture,” a study of memorials to the dead.

This was a new idea for Yale, but the topic was very much in the air after the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, Jr., and Burr was given the go-ahead. The course title was Funerary Architecture from the Stone Age to the Present. Nine students signed up. Among them was a bright, happy senior from Ohio named Maya Lin. The professor took his students through a number of exercises. He asked them to define the word “sublime” and to visualize it with a sketch. They were to imagine a design for a crematorium and a sarcophagus, and they were shown the famous design of French Beaux Arts architectural theorist Étienne-Louis Boullée for a memorial to Isaac Newton: a huge geometric sphere that was supposed to be the height of the Washington monument, but was never built.

The main requirements for Burr’s course were several design projects. Channeling Bartholomé at Père Lachaise, the students were to design a cemetery gateway at Durham, a charming little town north of New Haven. Next, with the memory of the 72,000 dead at Thiepval in the Sommes valley fresh in his mind, Burr asked his class to design a war memorial for the next future American war of their imagination, World War III.

As the semester proceeded, Maya Lin turned out to be an indifferent, prickly, and difficult student, one who did not take criticism well and developed a testy relationship with her professor. She neglected to finish assignments, notably the required notebook called “visual diaries” that were to preserve the student’s sketches. For the assignment to design a memorial for World War III, she turned in a dismayingly depressing drawing of a concrete tunnel strewn with trash and urine. It was a tomb, a study in frustration, where visitors would be trapped and unable to get out.

When Burr challenged her that this was not exactly an uplifting concept for a war memorial, Lin responded that she intended her concept to be ugly, since war itself was ugly and revolting. Would she want to visit such a place if her brother or friend were memorialized there? he asked. Lin characterized his question as “angry.” Her professor had not understood her concept, she wrote later. Nobody would still be alive after World War III, and she meant it to be empty and depressing. Burr took this simply as an excuse for a poor design.

—

The open competition for a Vietnam War memorial was officially announced in November 1980, and a brochure and a rules packet for it were sent to every art and architecture school in the United States, as well as to architecture and landscape firms. The planning commenced for what was anticipated to be an enormous response. But how was the contest to be administered? The VVMF board chose Paul Spreiregen to be its professional adviser. Spreiregen was a noted architect in Washington who hosted a weekly design program on National Public Radio and had written a book on design competitions.

Spreiregen’s first challenge was to oversee the selection of jurors who would determine the winning design. Eight distinguished architects and artists were tapped. Pietro Belluschi was an architect of elegant and sleek modernist towers, including the Pan Am Building and the Juilliard School of Music in New York, and a winner of the American Institute of Architects’ gold medal. The former dean of the architecture school at MIT, he was, at eighty-one, the oldest juror. Significantly, he was also a veteran of the Italian army in World War I. Harry Weese had designed the highly regarded Washington, DC subway system’s grand, commodious stations with coffered ceilings in the Brutalist style. He had a reputation as a sharp-tongued and witty contrarian. Jurors three and four were two notable landscape architects with national reputations: Garrett Eckbo, who had written a seminal book, Landscape for Living (1950), and Hideo Sasaki, former chair of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, whose masterworks were the plan for Copley Square in Boston and the grounds around Foothill College in Los Altos, California. There were also three renowned sculptors: Constantino Nivola, Richard H. Hunt, and James Rosati, whose various works were on display in the major art museums of Washington and New York.

And finally, Grady Clay, a gentle Kentuckian and the editor of Landscape Architecture magazine, was chosen as the jury chairman. He was a veteran of the Italian peninsular campaign in World War II, and his combat service would become important later.

With the eight jurors in place, the next consideration was the rules. Submissions would be accepted beginning in January 1981 and ending on March 31. The jury would examine the entries and choose the winner in late April. The purpose of the memorial was “to recognize and honor those who served and died.” The submissions should be “reflective and contemplative” in character, as a catalyst for a process of healing and reconciliation. Through the memorial, it was hoped that “both supporters and opponents of the war may find a common ground for recognizing the sacrifice, heroism, and loyalty which were a part of the Vietnam experience.” Artists and architects were to submit two rigid 30-x-40-inch panels with their concepts, including a visual representation of their idea, a description, and a statement of purpose. The description had to be handwritten, not typed or printed. Every concept had to include all of the names of those who had died in the war. All competitors had to be US citizens. No competitor was to indicate their identity on the illustrations. To do so would result in immediate disqualification, and the design would not be presented to the jury.

The most important rule was that entries be non-political. They were to express no opinion whatsoever about the rightness or wrongness of the Vietnam War itself.

The final footnote in the rules surely made many eyes roll. “Amateurs” were to have as much of a chance of winning as “professionals.” If an amateur should happen to win the contest but not have the skill or experience to execute their concept, the VVMF had the right to “supplement the skills of the winner with other necessary experts and consultants.” This too would become important later.

After the competition was announced, Professor Burr changed his course plan and assigned his students to design a memorial for the contest. On her Thanksgiving break, Maya Lin and three classmates traveled to Washington and walked the landscape of Constitution Gardens. There, her vision of a memorial was born. “Some people were playing Frisbee,” she would recall later. “It was a beautiful park. I didn’t want to destroy a living park. You use the landscape, you don’t fight with it. You absorb the landscape, fit the building into it and both are stronger.”

Of the eventual submissions for Professor Burr’s class, Lin’s was the most arresting. It consisted of a horizontal V, with tapered ends, and its vertex below ground. A series of slabs curved from the higher knoll above and ran downhill to the vertex, and it was upon these slabs that Lin proposed to carve the names of the Vietnam dead.

In the world of architecture this is called a pun, for Lin saw these slabs as dominos falling, suggesting that the dead were victims of the “domino theory,” the discredited rationale for the war which posited that, if Vietnam fell to the Communists, the countries around it—Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand—would then fall in quick succession. And so, the origin of the most successful, all-inclusive war memorial in American history was, in its inception, certainly not non-political. Quite the opposite: its foundation was a brilliantly devastating political commentary on the Vietnam War: that the “kids” of Vietnam took a dizzying ride on a series of falling dominos to their collective death.

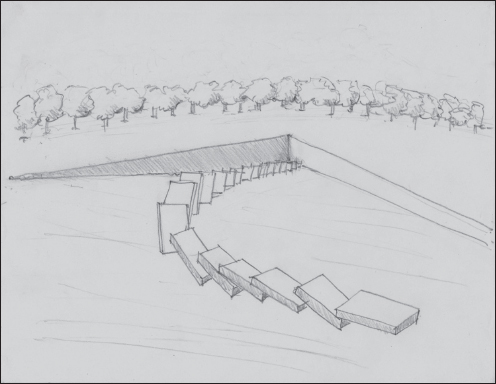

Professor Andrus Burr’s sketch recalling Maya Lin’s memorial drawing for a class assignment

To mirror the professional process of an architectural firm, Professor Burr recruited several faculty members to “jury” the class submissions. When it came to Lin’s design, the consensus was that a structure below ground was entirely appropriate for a failed war. It was remarked that Lin’s V actually suggested the edge of a coffin peeking above ground. But what were these slabs? What was their purpose? Did they not make a pointedly political statement that was forbidden by the competition organizers? It was suggested that she scrap the slabs altogether and leave the simple V as the final draft for this class exercise.

Lin had also proposed initially to arrange the names in the chronological order of their deaths. But that would diminish the importance of the V’s vertex, objected a juror. Lin acknowledged this as a weak point of the design. And so, in her revision, she changed the order for the final critique, making the chronological sequence begin and end at the apex, “so that the timeline would circle back on itself and close the sequence.” Besides closing the sequence, the configuration might also, metaphorically, be seen as closing a wound.

Lin received an A for her Vietnam assignment. Professor Burr would say later of the dominoes, “I, and my colleague Carl Pucci, criticized it as too literal and dumb. But we suggested that the V-shaped cut in the earth was a very strong gesture, and it alone conjured images of death, a coffin, entombment. We liked it.”

But at the end of the course, because of her other unfinished work, Burr first gave her a grade of incomplete. Upon seeing the grade, Lin stormed into his office and amid tears demanded that the grade be changed. She would never get into graduate school now, she wailed. Burr relented and changed the course grade. “I thought she understood that she was lucky to get a B+,” he wrote, later noting that “In the end, she certainly got back at me.” Maya Lin never forgave him. And Burr himself would resent her ingratitude for all he and his class had done for her.

—

The competition officially opened in early January 1981, and the entries began to pour in. Certain critical questions arose at the outset. Would the winner have a direct role in supervising the actual construction? Answer: “Our intention is that the author(s) of the winning design will participate in all appropriate aspects of the realization of the memorial, commensurate with skill and experience.” Who owned the winning design? The answer from the directorate was clear: the Memorial Fund would own it and have the exclusive right to build it. It would also own the rights to publish, display, reproduce, and publicize the winning design. For Maya Lin, this would become a sore point later.

But the most important question dealt with the requirement that the entries make no political statement about the war. How was a “political statement” to be defined?

Answer: “For purposes of the competition a political statement regarding the war is any comment on the rightness, wrongness, or motivation of US policy in entering, conducting or withdrawing from the war.”

There were also important, far-reaching questions that hovered over the contest. What segment of the population would ultimately control the memory of Vietnam? Would it be the veterans who were looking for vindication of their service? Would it be the artists who simply wanted to make a stylistic statement? Would it be the war resisters who sought a validation for the American defeat in Vietnam? Or would it be the politicians who simply wanted to allay the political pressures on them and put Vietnam to rest?

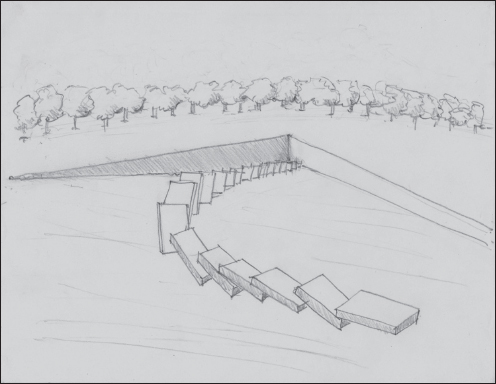

Professor Burr himself was among the early entrants to the contest. At his farm outside Williamstown, Massachusetts, where he kept his prized vintage tractors, he had gathered three other architects for a weekend of work and booze and jolly inspiration. Burr described his effort as a kind of “lark,” in which the professionals tried to channel what they saw as the “jingoism” of the contest. They came up with a wheel-and-spoke design with a raised central star and a series of upright slabs that were to contain the names of the dead. Ultimately, he and his colleagues went away unsatisfied with their “whiskey-fueled” work and acknowledged that it was scarcely competitive. They submitted it anyway, and then it was back to teaching.

Andrus Burr’s design entry for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial competition

Though the entrants had, by rule, to remain anonymous, the competition would include a number of architecture professors and well-known regional practitioners, as well as scores of art and architecture graduate students. Though most of the prominent architectural firms in the country passed up the contest, a handful of luminaries did participate. Charles H. Atherton, who was the chief executive of the US Commission of Fine Arts, the very body that would ultimately authorize the winning design, submitted an entry, as did Kent Cooper, the architect who was eventually chosen to execute the winning concept. More competitive was Samuel “Sambo” Mockbee, who already was exerting a huge influence on American architecture with his “rural studio” program in Alabama and who would be awarded the American Institute of Architects (AIA) gold medal after his death in 2001. Mockbee’s design featured a grove of pink dogwood trees and a raised circle, held up, in lieu of columns, by draped sculpted female figures, suggestive of the ancient Greek karyatids. Another entrant was a well-known California architect, Thom Mayne, a principal in the internationally notable firm Morphosis. Mayne was not only an AIA gold medal winner but in 2005 would also be awarded the Pritzker Prize, the equivalent of the Nobel Prize for architecture. His design presented a linear corridor of raised panels beneath an enclosed slit roof.

Samuel Mockbee’s design entry for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial competition

None of these luminaries made it into the semifinals.

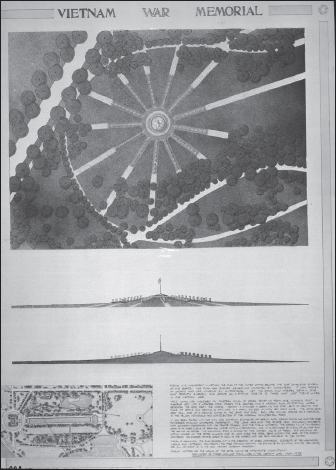

At the time, the eventual 1,421 submissions represented the largest number of entrants of any design competition in the history of American and European art. Collectively, the contest produced a tremendous effusion of creativity, some of which was remarkably original and some which was outrageous kitsch. In reaching for monumental grandeur, many of the entries overlooked the enjoinder to be “reflective and contemplative.” The most common offering was a circle or spiral such as that of Andrus Burr, where the names of the dead would appear on low-slung walls or slabs, so as not to compete with the temple of Lincoln to the southwest or the Washington Monument to the southeast. Stars and columns, pyramids and serpentine pathways were recurring features, as were dominos and pools of water. In one submission, soldiers waded through a pool toward a wounded, drowning comrade. A few submissions had the feel of a spaceship, while many others featured groves of decorative trees and scrubs. The central feature of one entrant was a giant teardrop, while another was entitled Tower of Lost Souls. A third displayed the gnarled detritus of a battlefield. Perhaps the most memorable absurdities were a pair of sixty-foot-tall combat boots and a rocking chair atop a forty-foot-high column, although a design featuring a massive combat helmet with two big bullet holes was also striking. From inside the helmet the visitor would gaze at the names of the fallen on dog tags that lit up.

Several notable submissions were overtly patriotic. One proposed an American flag that would cover the entire two acres of Constitution Gardens, while the central feature of another was a huge map of Vietnam itself. Several submissions had inscriptions. One read:

Let us to the end dare to do our duty as we see it

Please join me in a prayer for a better tomorrow

When the horrors of war and the infamy of men

Will belong to a forgotten people in a forgotten past.

Most of the designs were abstract, and there were relatively few realistic sculptures. A few had birds both lovely and grotesque. Gigantic bald eagles with wings spread wide were common. One displayed an epic man with wings; another, the Hand of God; while still another featured the figure of a combat soldier reaching out to a seated Vietnamese woman in a conical hat. And inevitably, in a bow to the movie Apocalypse Now (1979), a submission portrayed the three Valkyries riding heroically to heaven in Wagnerian glory.

The architecture critic Von Eckardt would write that the entries ranged from “architectural stunts to sculptural theatrics, from the pompous to the ludicrous, from the innovative to the reactionary.”

On April 27, 1981, the eight jurors gathered at Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington. In the vastness of Hangar Three, the 1,421 entries were arranged in long rows and mounted on panels at eye level. The display panels stretched some 1.3 miles along the corridors. There was a glitch during their installation, however, when in a far corner of the hangar an Air Force pilot revved up the engine of his jet and blew down all the panels. Once reinstalled, the display boards were identified only by number. Before viewing the entries, the jurors reviewed the rules. The enjoinder against any political message was again emphasized. They were reminded that the goal was to find a concept that was reflective and contemplative in character. One juror remarked that the memorial had to have “an expression of human tragedy.” While it should look at both death and at life, it should also look “forward to life.” As if in a psychiatric counseling session, they were all asked to express any preconceptions they had.

Then off the jurors went in their separate ways, pondering this hugely diverse display of imagination and inspiration, hoping for genius, and taking their personal notes. To facilitate the judging, Spreiregen had classified the entries as grotesque or weak, superior merit, and somewhere in between, although he was intent to tell the jurors that they were free to ignore his categorization. Occasionally in their meandering, jurors checked back with Spreiregen. Midway through the first day, Grady Clay, the chairman, said to Spreiregen in a gleeful stage-whisper, “I think there are several that might just work!”

On Day 2 each juror selected his favorites, less than 40 for each, and these were moved to a separate room. That reduced the number of designs under consideration to 232. The jurors then gathered as a group for the first time and paused in front of each entry for discussion. By Day 3, they had narrowed the number down to 39. At one point James Rosati thrust his finger in horror at a squiggle on one panel as if he had uncovered the black spot of Treasure Island. “What’s that?” he demanded of the pirate mark. Initials! The entry was immediately disqualified and removed.

Of course, some entries may not have been quite as anonymous as the organizers professed. For example, there were only a handful of entries featuring sophisticated sculptures with distinctive styles. One of those was Frederick Hart’s. The landscaper he had worked with to develop his design, Joseph E. Brown, was a principal in EDAW, a prominent landscape architecture firm; among the firm’s founders was Garrett Eckbo, one of the jurors. And Brown had worked on other monuments in Washington. He was confident of winning.

On the fourth day, the jurors had their eighteen semifinalists, as prescribed by the competition rules. As they tarried before each entry, the text describing the concept was read aloud to them.

At last they proceeded to the difficult choice of third place, runner-up, and winner.

For the third prize, they chose Frederick Hart and Joseph E. Brown’s design. It imagined a cove, a low, white granite wall of human scale, comprising two-thirds of a geometric circle that would have the feel of a sanctuary. Brown had cut windows to frame the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial. At ground level in the horseshoe, the names of the dead were carved into a scooped wall, at close proximity to the pathway, so that the visitor could sweep his fingers down the names. At various points in the wall, water seeped through small slits from the top down to a small channel along the base, suggestive of weeping. At the terminus of each of the wall’s prongs, there were two sculptures, facing one another across a meadow and an invisible line of tension. One portrayed a soldier carrying a wounded comrade, reaching out and calling for help. The other was a figure with an outstretched arm, rushing to help. Later, this concept would be described as heroic, but Hart had specifically tamped down the notion of heroism in favor of distress, poignancy and tragedy. The description of the design, however, was heroic: “The sculptures are meant to honor and evoke the sacrifice and valor” of the Vietnam soldier and be a “metaphor for reconciliation.” In denying this entry first place, one juror remarked that, while the design might be perfect for World War II, it was not so for Vietnam.

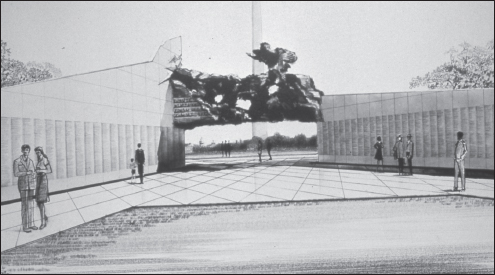

The second prize went to entrant #343. It was a fascinating composition of two facing U-shaped walls of different heights bearing the names of the dead. Joining the walls was a massive overhanging abstract sculpture that formed a bridge between the two walls. Where the sculpture joined the higher wall, the wall was fractured, as if to suggest the war that had fractured the United States. The crumpled bronze artwork reminded some of the cubist sculptures of Lithuanian artist, Jacques Lipchitz, or the lumpy expressionist sculptures of Reuben Nakian, though others found it more in the vein of socialist-realist, Soviet-style art. As it happened, the team responsible for the design was a Long Island group of Russian emigrés led by Marvin Krosinsky. It bore an inscription that Vietnam veterans would have found uplifting but that protesters might find debatable:

The Nation Divided, its People in Turmoil

A Conflict Unending and Controversial …

But their Spirit made This Nation One Again …

Its people United and its Principles Resolved and Firm.

The concept was perfect for World War I, a juror remarked, as if they were channeling Professor Andrus Burr’s assignment at Yale. But it was not right for Vietnam.

Competition design entry by Marvin Krosinsky, awarded second place

Throughout the competition, the jurors came back time and again to the haunting submission identified as #1026. “He must really know what he’s doing,” a juror remarked, “to dare to do something so naïve.”

Submission #1026 was startling in its differences from all the other entries. Against an abundance of precise drawings by more sophisticated competitors, this entry was a triumph of simplicity. At first glance, its two panels looked almost like the work of a high schooler by comparison, with the elemental black chevron like a floating mustache against a light blue pastel wash. In contrast to the fine geometric renderings of the other top contenders, this entry was ethereal and distinctly Asian in feel. Instead of the heroic labors of the others to fold softly into the existing landscape, #1026 proposed to cut deeply into the earth. Instead of comfortable words about heroism and service, valor and sacrifice, this submission had only a simple inscription: a large, gray rectangular panel with the words In Memoriam.

The handwritten words that described the vision of the artist imagined a “rift in the earth” in which a long polished black granite wall would emerge from and recede into the landscape. “Walking into this grassy site contained by the walls of the memorial we can barely make out the carved names upon the memorial’s walls.” The multitude of war dead would convey “a sense of overwhelming numbers.” And these names would be carved into the wall in the order in which they died in Vietnam, so that a stroll along the wall would become a chronicle of the Vietnam War from its first to its last American casualty. It would be up to each visitor “to come to terms with this loss.”

For death, in the end, the words proclaimed, is “a personal and private matter.”

The entry did not impress every juror. Chairman Clay found the display “sketchy” and “vague.” On the first pass, only three of the eight jurors thought well of it. But its strength and “deceptive simplicity,” in Clay’s words, grew on the jurors, and they kept returning to ponder its beautifully descriptive words. Hideo Sasaki, the influential landscape architect (who had been interned in the Poston, Arizona, camp for Japanese-Americans during World War II), was especially enthusiastic. In time, a consensus developed around it. They considered it to be far superior to all the rest.

On the morning of the fifth day, Clay gathered his notes along with the comments of the others as he prepared to write the jury’s verdict. The commemoration must have a sense of serenity, he wrote, and the wall of #1026 below ground would cut out traffic noise and thus achieve that desired effect. “Washington,” noted one juror, “is a city of white memorials, rising … this is a dark memorial, receding.”

“Many people will not comprehend this design,” one juror said of #1026.

“It will be a better memorial if it’s not entirely understood at first,” responded another.

But perhaps the most compelling juror observation was this: “Great art is like an unfilled vessel into which you can pour your own meaning. … Each generation continues to do that. … A great work of art is never complete and forever fresh.”

Clay later wrote, “The winning design is a great one. We believe it should be built as designed. It reflects the precise nature of the site designated by Congress. It is aligned beautifully with the Lincoln Memorial and Washington Monument … a unique horizontal design in a city full of vertical ‘statements.’ It uses natural forms of earth and minerals, without attempting to dominate the site. It invites contemplation and a feeling of reconciliation. The design, by creating a place of utter simplicity and serenity, is a work of art that will survive the test of time.”

When the label of #1026 was ripped off and the name revealed, the surprise winner was unknown to any of the jurors, an amateur and a young Asian-American woman by the name of Maya Lin. Of the winner, the juror Pietro Belluschi would say that a family’s background “has a way to penetrate and show in her work: [there is] a natural sophistication and sensitivity traditional in Chinese work.” And he would see her youth and naiveté as central to her achievement. “Her design rises above [politics],” he said. “It is very naïve … more what a child will do than what a sophisticated artist would present. It was above the banal. It has the sort of purity of an idea that shines.”

In the joint statement of all the jurors, there was this final praise: “This is very much a memorial of our own times, one that could not have been achieved in another time or place.”

Paul Spreiregen, the impresario of this extravaganza, was bursting with pride. He believed that his competition had been a model of fairness and professionalism. The result was a stroke of genius. The very simplicity and transcendence of entry #1026 reminded him of what that French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry had once said: “Il semble que la perfection soit atteinte non quand il n’y a plus rien à ajouter, mais quand il n’y a plus rien à retrancher.”

“Perfection is finally attained not when there is no longer anything to add, but when there is no longer anything to take away.”