AND THE WINNER IS …

“We believe it should be built as designed.” Those words of the final jury decision were fraught with latent significance.

In the few days after the jury’s decision, Paul Spreiregen began planning for the formal public announcement of the winning design. The chances of the memorial actually ever being built, he surmised, were extremely slim, much less built as designed. For that to happen, millions of dollars would have to be raised, not just one million as Jan Scruggs initially imagined, but seven million. Multiple Washington bureaucracies would all have to confer their blessing—the National Park Service, the National Capital Planning Board, the Commission of Fine Arts, and perhaps, most daunting of all, the acerbic, ultra-conservative secretary of the Interior, James Watt. Pencils were sure to be sharpened.

There were more immediate concerns. Maya Lin had won only with an idea, just a figment of her fertile imagination. She had no expertise in building or in landscape architecture or in engineering. There would certainly be technical issues with a structure that was built below ground level. If the wall at its vertex was ten feet high, there was real danger of people falling off. What was the impact of that danger on the design? A need for an unsightly fence or an additional wall? For the impending press conference, what would the critics say, especially the prickly architecture critic of the Washington Post, Wolf Von Eckardt? Would there be sore losers, especially the luminaries of art and architecture who might set out to denigrate the winner? And finally, what would the VVMF veterans think and say, not only in public but also in private? Their initial reaction seemed positive. When the patrons were taken to see the winning design, there was a pause before Jan Scruggs said “I like it.” And another veteran and colleague, John C. Wheeler, said, “I think it is a work of genius.”

They got it, Spreiregen told himself. What about the others?

In fact, Scruggs instantly had private doubts. His first thought was that the design looked like a bat. Then he saw it as a boomerang that people would latch onto as an analogy to the lost war: that the thing was flung out, and then it would come screaming back to coldcock you. Then he saw a black hole in the ground. The choice was sure to occasion an immense public relations headache, he thought prophetically.

The announcement had to have maximum dramatic effect.

Additionally, there was the question of the winner herself. When they pulled off the number of the entry to reveal the name and then her details, they had to wonder: Who was this undergraduate? What did she look like? How mature was she? How would she act and react? Were there implications from the very fact that she was of Asian extraction? Building her up as a credible choice was central to a successful launch. But would she satisfy?

It was the last day of spring semester classes when her roommate rushed to tell Maya Lin that a call had come to her from the Washington competition committee. They wanted to come and see her; they had a few questions to ask about her design.

“Don’t get your hopes up,” a voice on the line said. Lin did not confer much importance to the impending visit. She might have made it into the top one hundred, she thought. They were probably coming with disqualifying technical concerns like drainage. Besides, she was preoccupied with packing up and getting out of town.

At her dorm door the next day, along with two other colleagues, stood a retired US Marine colonel, Donald E. Schaet, an artillery officer with the infantry in Vietnam and a recipient of a Bronze Star medal with combat V, denoting combat valor. He was an unusual visitor in the corridors of Saybrook College at Yale. For all his record of military bravado, Colonel Schaet turned out to be rather soft-spoken and unpretentious, in a very un-Marine kind of way. But he was also skilled in recruiting and press relations. He would make a good defender later.

His discourse began with words on the unparalleled magnitude of the competition itself, the largest of any art contest in all of Europe and America, and how many truly worthy contenders there were. The preamble sounded like a rejection. Maya Lin braced herself for the inevitable.

Oh, and by the way, Colonel Schaet said at last, she had won the competition.

—

With the formidable Marine dispatched to New Haven to invite the winner to Washington, Paul Spreiregen began his frantic preparations for the public announcement. At the competition offices, the phone was ringing constantly, with competitors in high anticipation of the results. Joseph Brown, the landscape architect whose horseshoe and weeping water design with its Frederick Hart sculptures made a strong contender, was especially persistent and aggressive. Should he be preparing his remarks for his acceptance speech? he asked. Spreiregen was appropriately mum.

Meanwhile, the architect-juror Harry Weese quietly offered the services of his Washington office to build several scale models of Maya Lin’s design. They had only an idea, and now the idea had to be developed and given a sense of reality, far beyond the mysterious, floating chevron in a sea of azure blue. A professional, experienced firm was needed to execute the design. Not only did a memorial below ground level present serious engineering problems, but the dimensions of scale had to be made larger to accommodate all the names. That required that the wall be about ten feet tall at its vertex, and that in itself made safety an even greater issue. The challenges were formidable.

Once the models were hastily finished, they were photographed from different angles for a parallax view, and these were rendered into a slide show. A slick press release was crafted to create an aura around the surprising winner. Maya Lin’s story was as important as the memorial itself.

“It has to be love at first sight,” Spreiregen thought. “Or it is dead.”

On the day of her graduation from Yale, Maya drove to Washington. Once there, she was taken immediately to see the models … and she was horrified.

“You have changed my design!” she exclaimed and turned on her heel to walk out. “I never want to see you for the rest of my life!”

The managers looked at one another in amazement and befuddlement. Was she crazy? Was she out to scuttle the whole thing? She was going to be a problem.

Good reporter that he was, Wolf von Eckhart was immediately onto this remarkable outcome. Soon enough he found out where the winner was staying and sought her out, taking with him his friend and colleague, Judith Martin. When Lin appeared, they were amazed. She looked much younger than her twenty-one years, especially in her oversized Yale sweatshirt and horizontally striped knee socks. Von Eckhart was lavish in his congratulation, gushing his enthusiasm for the design, extolling its simplicity, its naturalness, its lack of jingoism.

“It’s so Taoist,” he exclaimed.

“I don’t know anything about that,” Lin replied flatly.

They had expected her to be over the moon with triumph and a bit in shock. Instead, she was visibly in distress. Their hearts went out to her.

“They look at me, and they don’t see an architect,” she cried. “They” were Spreiregen and his imposing, self-important colleagues. They were taking her design away from her, she burst out, and they were beastly and patronizing besides.

Von Eckhart and Martin exchanged meaningful glances. This was a young lady who needed to be taken in tow. Maya Lin’s debut was only a day away. And so, the future Miss Manners, feeling very maternal, hustled her off to the toniest store in town, Garfinckel’s, for a do-over. There, on the spacious third floor for exclusively designer clothes, Lin tried on a number of outfits, feeling quite out of sorts. Wasn’t Frank Lloyd Wright an eccentric dresser? she asked.

“Honey, when you become Frank Lloyd Wright, you can dress any way you like,” Martin replied tartly. They settled on a gray suit and stylish shoes. Lin balked at a hat. And then it was downstairs for makeup to make her look just a little bit older.

On May 6, 1981, the circular jury room at the headquarters of the American Institute of Architects had been made ready for the announcement. Fifteen honorable mention entries would be identified first. For suspense, the first, second, and third place finishers were under cover. Amid the crush of press and cameras, the landscape architect, Joseph Brown, stood with his sculptor, Frederick Hart, reasonably certain now that they had not won. He was confident that their entry had all the right aesthetic and political elements for victory. And he had all the right connections in the Washington architectural community and in the even smaller community of public art mavens. But he was getting the sinking feeling that all those factors might not be enough.

Spreiregen made a few remarks on the breadth and fairness of the competition, and then uncovered the second and third place finishers. Brown and Hart took a disappointing third place. And then it was Scruggs’s turn to announce the winner. Off came the cover, and there was an audible gasp as petite Maya Lin stepped forward to greet the assemblage, her luxuriant hair cascading to her shoulders over a simple, demure white shift. When she addressed the assemblage, only her head peeked over the podium. She giggled as she told of Colonel Schaet’s visit to her dorm room and his remark not to get her hopes up. Joseph Brown could scarcely mask his surprise. Their effort as a leading architectural firm with a sculptor of national reputation and an associate who had won the distinguished Rome Prize for architecture had been bested by a college student with a class exercise. And yet, he saw instantly that his entry had lost for being too complicated. As the chairman of the jury told him later, their entry was “too literal.” Maya Lin had captured something Brown and his associates had missed. Her design was simple and strong, if “negative.” Brown felt no resentment, only resignation. Hers was better.

She took a few questions. Eventually, the inevitable question came. Since she was an “Oriental person,” and since many Asians had died in the war, how did she feel about that?

With the inscrutability of the Dalai Lama, she answered, “It doesn’t matter.”

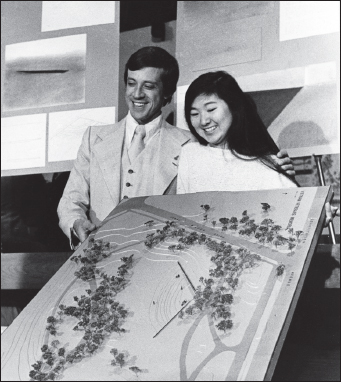

Jan Scruggs and Maya Lin at the announcement of the winning design, May 6, 1981

Afterward, she was escorted to a number of individual interviews. Openly and without hesitation, she admitted that she didn’t know much about the Vietnam War. When asked about her artistic intention, she quotably answered, “I wanted to describe a journey—a journey which would make you experience death.”

The next day, the headline in the Los Angeles Times was:

STUDENT WINS VIETNAM MEMORIAL CONTEST

CHINESE WOMAN, 21, GETS $20,000 FOR WAR MONUMENT DESIGN

In the Washington Post, reporter Henry Allen, a Marine combat veteran himself and more skeptical than his colleague Wolf von Eckhart, led his story with this sentence: “For the dead whom few wanted to remember after a war few could forget, a woman who was four years old when the first bodies came home has designed a national memorial to be built on the Mall.” And deeper in the story, Allen wrote, “Her design does not mention the war itself, or the Republic of South Vietnam, only the names of the dead.”

The naysaying had begun.

—

Maya Ying Lin was born in 1959 in the southeastern Ohio town of Athens. She was the daughter of Chinese immigrants; her father was raised in Fujian province in southeastern China and later in Beijing in a family of well-to-do scholars and statesmen. Her grandfather had been the Chinese delegate to the League of Nations in 1921, and the family could trace its ancestry back to the eleventh century. Her father’s upbringing had been strict, at a time when children of the upper classes were drilled in calligraphy and music along with other core subjects. As the Sino-Japanese War began in 1937 and then merged into World War II, Huan Lin nevertheless enjoyed a comfortable, carefree existence as a university administrator. Maya Lin’s mother, Ming-hui, hailed from a family of doctors that included women physicians. But as the Communists took over the country in 1949 and set out to quash the upper class, the specter of re-education camps loomed, and it was time to flee. With fifty dollars sewn into her coat, Ming-hui was smuggled out of Shanghai in a junk as Nationalist planes bombed the harbor.

In fleeing China, the refugees had lost everything and, once in America, had to begin anew. Huan Lin gravitated back into academic administration, but he also schooled himself in the art of pottery, an avocation that was probably inspired by his father, who had possessed a magnificent collection of Chinese ceramics and porcelain. The style of Huan’s pottery was decidedly more Japanese than Chinese, accentuating the rustic simplicity of the Zen aesthetic. No doubt, the Japanese wartime occupation of Fujian province influenced him. (That simple, minimalist, Japanese-influenced aesthetic would come to characterize Maya Lin’s later work.)

Her parents met in Seattle and were married in an Episcopal Church in 1951. The family moved to Athens after Huan, now calling himself Henry Lin, was invited to join the faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Ohio. In time he rose to become the Dean of Fine Arts. He would also achieve considerable renown as an award-winning potter, displaying his work in exhibitions far beyond Athens. When their daughter was born, they gave her an Indian name, Maya, the name of Buddha’s mother, that means illusion and evokes emptiness. In Hinduism, Maya is a sobriquet for goddess.

“I’ve been an artist from probably the first time I stepped into my dad’s ceramics studio,” Lin would say. Her mother, meanwhile, earned a graduate degree in English and Chinese literature, with a thesis that fused the poems of William Butler Yeats with Indian philosophy. In 1965, now known as Julia Lin, she got her doctorate with a dissertation on modern Chinese poetry and taught in the university’s English department.

As a child and a “faculty brat,” Maya Lin found the hilly landscape of southeastern Ohio beautiful and fascinating. The Lin house was deep in the woods, and she came to imagine the trees on the ridges above the house as spines growing out of the earth. A great lover of birds and animals, she mourned the devastating damage that DDT, the chemical scourge about which Rachel Carson wrote in her seminal book, Silent Spring (1962), was visiting on Lake Erie and on bird populations.

“This is so unfair that one species can do this to another species,” the young Maya said to her mother once. “We have more of a responsibility.”

Inwardly directed in her close-knit family, with its concentration on art and learning, she excelled at school, especially in math and science. With her love of animals, she supposed that she would become a veterinarian or a field zoologist. Even as a superior student, she was constantly making things with her hands in deference to her father. The Department of Fine Arts was her playground. A “clean aesthetic” epitomized the art of the family household, and there was great respect for the creative process.

Her adolescence, however, had been a struggle for identity. Her parents wanted her and her brother, Tan, to fit in, to assimilate, and told them both that they only wanted their children to be happy. Henry Lin was intent not to repeat the strictness of his own upbringing in China. The children were left alone to grow as typical Americans and follow their own passions without heavy-handed direction. But in that small Midwestern town, their differentness was evident. Though Lin did not regard herself as anything other than an ordinary American kid, she was something of a misfit. By her own admission, she had only a few friends. Somehow, she did not “belong.”

When it came time to apply for college, she was in a good position to reach high. She had the highest grade point average in her high school class and was its valedictorian. Yale admitted her swiftly. Once there she was seen as reserved and apolitical. She was disinterested in extracurricular activities. In her third year, she gravitated toward a major in architecture.

“I chose architecture,” she would say later, because “it was this perfect combination of science, math, and art.” Architecture was her harmony of opposites, art and science, her yin and yang. She would say that she had to suppress the analytic side of her brain to do her art. She began to lay her groundwork with courses in form and function, place and dimension, and the basic theories of architecture.

Importantly, she would take what was then the best-known undergraduate course in Yale’s Architecture School, “History of Modern Architecture and Urbanism,” taught by its most famous professor, Vincent Scully. As it happened, it was in Scully’s class that a seed was planted for the future. Like Professor Burr, Scully too had covered the World War I monument at Thiepval in Sommes, France, in his course. The “yawning archway” of the great cenotaph, incised with names of the dead, was like a “gaping scream,” Scully told his students, as the tombs of seventy thousand soldiers were spread before you. It was a realization of immeasurable loss.

It wasn’t until her junior year that Lin’s consciousness about her ethnicity rose to the surface. During a semester abroad in Denmark, tanned under the brilliant northern sun, she was often mistaken for an Eskimo, and it was not a pleasant experience since the Danes tended to discriminate against the aboriginal “Greenlanders.” It was as if her eastern sensibility was bubbling up from within. When she would disabuse the Danes of their Eskimo fantasies by saying she was Chinese, a common response was: “Oh, so do your parents own a restaurant or a laundry?” Or if, back in the States, she would get in a taxi, a common question was, “Where are you from?” Answer: “Ohio.” Counter-response: “No, no, I mean where are you really from?” And then there was the stereotype in the movies that especially infuriated her, of the docile, servile Asian woman.

“No matter how long you’ve been here,” she would say about her roots, “you’re not going to be quite allowed to be American.”

While in Denmark, Lin, now fully committed to her architecture major, took an interest in the Nørrebro cemetery in Copenhagen. The psychological and emotional power of cemeteries fascinated her. In a small European country where land is scarce, cemeteries double as parks, and people spend pleasant hours in leisure with no reference to the dead. This tie to the land became central to her aesthetic development.

“All my artworks,” she would say later, “deal with nature and the landscape. … It’s how you experience the land. … The Vietnam Memorial is an earth work.”

She would eventually bring that Danish insight to her work in Professor Burr’s class. For his Vietnam memorial assignment, she began to channel her deepest instincts, returning to the aesthetic of her upbringing. After visiting Constitution Gardens over Thanksgiving and back at her Yale cafeteria, she sketched her idea of a simple V in a helping of mashed potatoes.

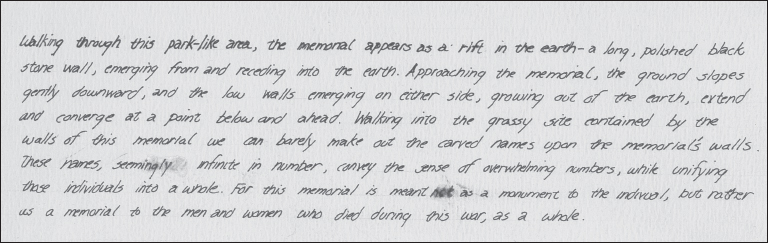

Her impulse was simply to cut into the earth. “I imagined taking a knife and cutting into the earth, opening it up, and [with the passage of time] that initial violence and pain would heal,” she told Bill Moyers in a 2003 PBS interview. “The grass would grow back, but the initial cut would remain a pure, flat surface in the earth with a polished, mirrored surface, much like the surface of a geode when you cut it and polish the edge.” Her design was not a wall, she would insist, but an edge to the earth, an opened side. She chose black granite to make the surface reflect like a mirror. The effect, she surmised, would double the size of the park.

A name can bring back every memory one has of a person. A name alone is more “comprehensive” than a still photograph or a sculpture. “Literally as you read a name, and touch a name, the pain will come out,” she would say. “I really did mean for people to cry … of your own power, [you have to] turn around and walk back up into the light, into the present. But if you can’t accept death, you’ll never get over it.” Her memorial, she insisted, was about honesty.

Moreover, her decision to place the names in the order in which soldiers died would provide a timeline for the longest war in American history. The names then would become the memorial, but also a narrative of the war. In the sparseness of the simple V, there was no need to embellish the design further. “The cost of war is these individuals,” she would say. “It’s [about] the people, not the politics.” It would be, she said, the interface “between our world and the quieter, darker, more peaceful world beyond.” Its apolitical nature was its essence.

“I did not want to civilize war by glorifying it or by forgetting the sacrifices involved,” she wrote later. “The price of human life in war should always be clearly remembered.”

As the issue would later be drawn, this was the dialectic between abstract and realistic art. When she began to think about Vietnam, there was no single image that came to her mind, like the photograph of the Iwo Jima flag-raising from World War II. Moreover, a realistic sculpture was only one interpretation and specific to only one time. She thought of a memorial as music in the way music can make a person laugh or cry, totally in the abstract.

“That abstraction can be human and relate to you. And that’s where the name … everything about that person will come back in the name.”

In the winter of 1981, when she was completing her entry to the grand competition, she seemed to realize that her elemental chevron floating in a sea of pastel blue would not be enough to make her entry competitive. The design was too simple to be noteworthy, and the overall concept was focused only on the dead. She doubted that it would be chosen.

“It wasn’t a politically glorified statement about war.”

Her entry’s accompanying description was everything. It had to be right. And on that, she had writer’s block. So, she sought out Vincent Scully, whose course had had such an impact on her. Sensing her struggle, Scully again pulled out slides of the Thiepval Memorial in France that had so moved Professor Andrus Burr the preceding summer. As she viewed the simple graves and the gargantuan cenotaph, the dam broke, and she picked up her pen and began to write. Her poetic brother, Tan, who was then studying at Columbia University, became her literary adviser.

“Writing is one of the purest arts,” she would say years later. “I value writing. I respect it. I find it the most difficult thing for me to do, but when I’m done, I am unbelievably just at peace. If you think about art as being able to share your thoughts with another, writing is totally pure.”

Portion of Maya Lin’s handwritten paragraph, from her competition entry, describing her design

Though she could not know it then, it was ultimately her writing that won the competition for her.

From the fortunate timing to Professor Burr’s guidance, to the minimalizing and depoliticizing of her concept of falling dominos, to her realization about the value of simplicity, to her gritty persistence and her essential talent, developing her design had been an evolutionary process. She had succeeded in making history apolitical.

“I have just dealt with facts,” she would say. “It’s what facts you choose to portray that focus you. It’s always about giving to people information and letting them read into it what they will.”