FIGHT AS HARD AS YOU CAN

A week before the official announcement of the grand competition for a Vietnam War memorial, Ronald Reagan trounced Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election. During the campaign, Reagan had addressed memory of the war only once. On August 18, at the convention of Veterans of Foreign Wars, which was endorsing his presidential bid, he rattled the rafters with a stem-winder. “America has been sleepwalking far too long. We need to snap out of it,” he proclaimed. The United States could have defeated the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army, if only Americans had not been bamboozled by North Vietnamese propaganda. Presidents Johnson and Nixon had let American soldiers down when US officials had suffered from a lack of will. That war was a “noble cause,” he thundered, in which the United States came to the aid of a small, beleaguered country, fresh from colonial rule, a nation that called out for help against a “totalitarian neighbor bent on conquest.”

And now, Reagan said, America was suffering from a malady called “Vietnam syndrome.” Moral anguish over war’s devastation and despair over the loss of life were gripping the country and paralyzing American leaders, making them timid in employing American power. “We dishonor the memory of fifty thousand young Americans who died in that cause when we give way to feelings of guilt, as if we were doing something shameful,” the Republican nominee said. In all this Reagan found a lesson. “We will never again ask young men to fight and possibly die in a war our government is afraid to let them win.”

Afraid to win? This revisionist fantasy—that the United States could have “won” in Vietnam, if only more bombs were dropped, more lives were lost, more years of struggle were endured—would persist for decades, infecting the way the Pentagon itself dealt with this dark chapter of its past. Meanwhile, a Harris poll earlier in the year reflected a contradiction in the public mind. Sixty-four percent agreed with the statement that Vietnam veterans “were made suckers” by their government, while at the same time more than 90 percent felt those same veterans deserved more respect for having served their country during a difficult time.

In January 1981, as the design submissions for the memorial began to pour in, the new president chose his cabinet. Little noticed at first amid his higher-profile choices was his pick for secretary of the Interior. James Watt, a Wyoming lawyer, would become a central player in the Vietnam Memorial saga. Before Watt resigned under pressure nearly three years later, he gained a reputation as the most hostile steward of the environment in history, pushing for aggressive drilling and mining on public lands and significantly reducing the number of endangered species under federal law.

Watt also had authority over what happened on the National Mall and what could be built there. In the spring of 1983, he banned rock concerts on the Mall, which was regarded as rebuke toward the Beach Boys, who had performed the previous year. Watt justified his decision by saying that rock acts attracted “the wrong element” and encouraged drug abuse and alcoholism. Suddenly, Watt became arguably the most reviled man in America, and even President Reagan’s wife, Nancy, announced that she was a fan of the Beach Boys. Later, Watt confessed that he’d never heard of the Beach Boys, one of America’s most popular and successful bands.

“If it wasn’t ‘Amazing Grace’ or ‘Star Spangled Banner,’” Watt later said, “I didn’t recognize the song.”

—

After Maya Lin’s design was chosen and announced, the public reaction was intense. Letters from outraged veterans poured into the Memorial Fund office. One claimed that Lin’s design had “the warmth and charm of an Abyssinian dagger.” “Nihilistic aesthetes” had chosen it. The design evoked the digging and hiding that a soldier had to do to survive in Vietnam. The proposal reflected the true situation of the Vietnam veteran: “bury the dead and ignore the needs of the living.” An Army major called it “just a black wall that expresses nothing.” Predictably, the names of incendiary anti-war icons, Jane Fonda and Abbie Hoffman, were invoked as cheering for a design that made a mockery of the Vietnam dead. There was positive reaction too, but the negative feedback captured the attention of the organizers.

This was only the beginning. Things were to get much worse.

The divide between a potent veterans cadre and critics with authentic artistic sensibilities was beginning to take shape. In a laudatory editorial, the Washington Star found Lin’s design contemplative with healthy doses both of pride for the veteran and reconciliation for the nation. The New York Times architecture critic, Paul Goldberger, pronounced the concept as “one of the most subtle and sophisticated pieces of public architecture” ever proposed for a city known for its haughty and grandiose installations.

And Wolf Von Eckardt, the dean of the architecture critics and arguably the godfather of the competition, gushed with enthusiasm. In a Washington Post piece entitled “The Serene Grace of the Vietnam Memorial,” he conceded that the design was unconventional, as unconventional as the Eiffel Tower. “It is,” he wrote, “a direct evocation of an emotional experience, which, one way or another, is what art is all about.” It might take time for its grace and power to be appreciated. “Its emotional impact … will take effect slowly, taking hold of the mind before the understanding quickens the heart.”

Not all the critics were so smitten. Paul Gapp, the architecture critic at the Chicago Tribune, called the design “inane” and bemoaned the sheer poverty of modern architecture to have produced something so dreadful. The judges were simply disconnected from public taste, he fumed, and he did not think the public would stand for it. The design, he wrote, was akin to “an erosion control project.” A colleague of his on the Tribune, Raymond Coffey, a Vietnam veteran, wrote in an opinion piece, “It is as if the very memorial itself is intended to bury and banish the whole Vietnam experience.” Charles Krauthammer, at his acerbic best, wrote in the New Republic that the only purpose of the design was to emphasize the “sheer human waste, the utter meaninglessness of it all.” It treated the Vietnam dead like “victims of some monstrous traffic accident.”

This mixed reaction among the critics and vets paled next to the critical arena of fundraising. What would the donors, especially Ross Perot, think of the design?

With his large financial investment in the competition and swelling with patriotic fervor, Perot had waited anxiously to hear about the winning design. When he was told about the black wall, the Texan was decidedly negative, and when he saw the design model, he was apoplectic. Dismissing Scruggs’s plaudits for the design as a magnificent work of art, Perot remarked that it might be great for those who died, but it said nothing about the two million who served and survived. Scruggs pleaded with him, at least, not to broadcast his disapproval. If the press asked him, Perot replied, he would say he didn’t like it. But he promised, for the time being, that he would not overtly publicize his attitude.

As for the winner with Chinese ancestry, Perot began referring to her as “egg roll.”

—

Maya Lin moved into an apartment on Capitol Hill in Washington in June 1981 and stayed for a year. After her momentary shock at her triumph, the weeks and months that followed were excruciating for her. She came to think of that horrible year as a war between herself and the entire Washington establishment. At every turn, she felt, politicians, architects, landscapers, veterans, and bureaucrats were trying to alter, water down, and defile her design, forcing her to cede control to lesser, prosaic individuals. In her dogged defense of her vision, she alienated almost everyone with whom she came into contact. She was abrasive and undiplomatic; compromise was not in her blood.

The first challenge was to find a collaborator who could execute her brilliant design, for at least she acknowledged that she was inexperienced in architectural practicalities. This problem led to the first real skirmish in the coming war. The veterans were indebted to Paul Spreiregen for his deft and professional handling of the complex competition, and so he seemed like the natural choice to become the “architect of record.” Stiffly and high-handedly, the VVMF patrons presented their choice to her as a fait accompli.

She reacted badly. She had already taken a considerable dislike to Spreiregen (and he to her), largely because he had told her bluntly of the flaws and difficulties of her design. Perhaps more annoyingly, according to Kent Cooper, who eventually became the architect of record, Spreiregen pushed for equal billing for implementing the design. On that point, she put her foot down: no one would share equal credit with her. Weeks of tense, angry discussions followed. At one point, according to Lin, the VVMF veterans warned her that she would come to regret her uncooperative, hostile behavior. Soon enough, her tormenters said, she would come “crawling back on [her] hands and knees.” It was not a good way to win her cooperation.

She fled to Yale. There, the entire university, especially among the luminaries in the architecture school, stood in awe, disbelief, and soaring admiration at her accomplishment. Her renowned mentor, Vincent Scully, shook his head in astonishment. “There’s nothing really like it at all. It doesn’t make any specific gesture which can date it in time or in place. It’s all wars, all death, all living and all dead … at once! It’s a remarkable thing and done by a girl of twenty or whatever, it’s really unbelievable. It’s really hard to grasp.”

The dean of the Architecture School, César Pelli, was also among her fervent admirers. To him, her design was amazing in capturing the enormity of the Vietnam conflict. It had touched his heart profoundly, as a triumph of the abstract. That an undergraduate student had conceived this stroke of genius was all the more impressive. In New Haven, she threw herself on Pelli’s good graces for advice and protection. The tall, smiling, easygoing Argentinian, who was already a towering figure in American architecture, listened sympathetically as she spilled out her anguish at being eaten alive by the Washington insiders. When she was finished, he began by instructing her in a fundamental truth: in the world of construction a marked difference exists between the designer and the builder. She was the artist, and once a design of an artist is accepted and paid for—she had collected her $20,000 prize—that person has virtually no rights.

Pelli knew what he was talking about. At that very time, he was engaged in a renovation of MOMA (the Museum of Modern Art) in New York. Once his concept was accepted and he was paid for it, the entire project was summarily changed in the subsequent iterations, and his plans ended up in the waste basket. He mentioned how many times the same thing had happened to the brightest lights of their firmament, known as “starchitects,” including Philip Johnson himself. Pelli spoke of how in the Renaissance great paintings were painted over, cut up, and the canvas reused. “If I design a building and get paid for it, the buyer can paint it purple, and I have no say in the matter,” he told her. Her design had won, and she had been paid. She had to deal with that fundamental fact.

“You may not be able to do anything,” he counseled. “But fight as hard as you can!”

The dean did, however, have a specific suggestion. He recommended an old friend, a Washington architect named Kent Cooper, as her collaborator.

“He will protect you,” Pelli assured her. And moreover, he could be a mentor.

Kent Cooper was a well-known figure in Washington architectural circles. He had been a brilliant, prize-winning student, and Eero Saarinen had recruited him in 1958 straight out of graduate school to work on the completion of Washington’s Dulles International Airport. In that association, he had learned patience. The airport was supposed to be finished in eighteen months; it took seven years. And in his later years, Cooper hung a large portrait of the modernist hero, Le Corbusier, in his office with his dictum, “Creation is a patient search.”

Cooper had gone on to develop a reputation as the avatar of modernism in Washington architecture, designing churches, schools, community centers, and libraries—even an installation at the Washington Zoo that earned the word “humane.” On his arrival in the capital, he found Washington architecture a boring wasteland of neoclassical buildings. But Dulles Airport, and later the Washington subway system (1976) and East Wing of the National Gallery of Art (1978) became prime examples of a new, modernist trend. In due course, Cooper would add Maya Lin’s memorial to that distinguished company. He would refer to it as the landmark and iconic memorial of the postwar era.

“There hasn’t been a commemorative piece before or after that has had the same impact,” he would say. But that flattering remark came long after his difficult collaboration with Maya Lin.

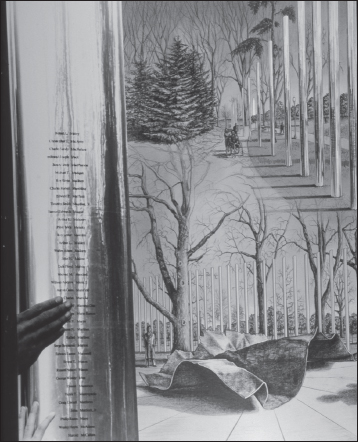

Though Lin did not know it, Cooper had submitted his own design to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial competition. It featured a long row of aluminum pylons upon which the names would be photographically etched. By design, those names were meant to fade in twenty years, and this fading was central to his notion of fleeting memory. The centerpiece of the design was a crumpled piece of bronze that symbolized death. Cooper’s design had made it into the top forty-eight, but no further.

Kent Cooper’s design entry for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial competition. The hands on the lower left are part of the design and show how visitors might touch the names inscribed on the columns.

Lin returned from Yale and her talk with César Pelli and presented Cooper’s name to the skeptical veterans, who were set on Spreiregen. The resistance in the VVMF to an unfamiliar outsider was considerable. Brusque and uncompromising as always, Lin saw her relationship with her patrons deteriorate further. Once again, her newfound booster, Wolf von Eckhart, stepped into the fray to calm the waters, pushing the veterans to listen to her. She was the winner of their contest after all, and besides, she had retained legal counsel to protect her interests. Eventually they had no choice but to capitulate, for she still possessed a semblance of veto power. Spreiregen was out, and Cooper was in. It was a victory that Cooper could only half celebrate. And in his ousting, Spreiregen could only half mourn, saying, “Working with Lin had no great appeal for me.” In her first meeting with Cooper, Lin delivered a stiff warning.

“You have no responsibility for the memorial. You will get no credit for it. Just make my design work!”

It was a good thing that patience was Cooper’s watchword, for in the coming months his patience would be sorely tried. Through the entire saga in which she was the central figure, Maya Lin would keep a steely focus on her artistic vision and cared little about hurting the feelings of her collaborators. It would be jarring later to hear a participant say, “Maya did not walk away from Washington with a single friend.” Friendship was never her concern.

Diligently, Cooper set about making detailed drawings for the construction. An early challenge was to determine the size of the wall’s surface, so that it could accommodate all 58,000 names. This required that the size of the wall as originally conceived had to be doubled and its height extended. Cooper wanted a railing, so people wouldn’t fall off the top. The military wanted a raised bandstand above the wall for their events. Lin vetoed both ideas.

A more difficult issue was her insistence that the names be inscribed in the chronological order of their deaths, thus providing a timeline for the war itself from 1959 to 1975. This was a startlingly original idea. Her collaborators, however, groused that such ordering would be an inconvenience or worse, an annoyance for visitors. The requirement to search a telephone book-sized index for the name of a loved one would be a turnoff, and if that system was adopted, the tattered book would probably have to be replaced every month. Lin fought back. A timeline of names was central to her vision.

“I knew the time line was key to the experience,” she would say. “A returning veteran would be able to find his or her time of service when finding a friend’s name.” Only when she pointed out the obvious—if you listed all the slain Smiths in alphabetical order, the effect would be prosaic and mind-numbing—did the patrons come around on the issue.

Another area of contention was the thickness of the wall itself. The granite had to be razor-thin, Lin insisted, consistent with her vision of a cut or a rift in the earth. Cooper wanted it thicker and thus more durable, since thin granite would be fragile and difficult to work. The notion of reflective granite was new to him. But, as she would later say, “a massive, thick, stone wall … was not my intention at all.” To thicken the wall was to undermine her metaphor. She would not have it.

“I always saw the wall as a pure surface, an interface between light and dark, where I cut the earth and polished its open edge,” she would say later. A thin surface reflected the vulnerability and pathos of the soldier’s experience. Reflection was the point. It allowed the visitor to see himself mingled within the names of his fallen comrades and thus ponder the bracing thought of “there but for the grace of God go I.” While Cooper argued against her thin, granite panels as too fragile, others argued against a polished surface as too feminine.

Then there was the matter of color. What was the significance of black anyway? “I do not think I thought of the color black as a color,” she wrote later, sharing the widespread artists’ view that black is the absence of color. “[It was more] the idea of a dark mirror into a shadowed mirrored image of the space, a space we cannot enter and from which the names separate us, an interface between the world of the living and the world of the dead.” White granite does not reflect the image of the viewer.

“If it were white,” Lin would say, “it would blind you because of the southern exposure. Black subdues that and creates a very comforting area. … [Black] makes two worlds. … It’s a mirror.” In listening to such an esoteric argument, the veterans were in over their heads. Black was black, dark, intimidating, soul-withering.

The last contention was the matter of the inscription. The veterans were pushing for a pithy phrasing to glorify their service, heroism, and courage. Lin resisted. She wanted only the “In Memoriam,” as stated in her proposal. She argued forcefully that a politically charged statement would destroy the apolitical nature of her design … and narrow and limit the appeal of the place over time. At this early stage, she was operating only on instinct. Her vision of her monument as all-encompassing, embracing the entire Vietnam generation, both for and against the war, was still inchoate. Only later would she state openly that this was not merely a veterans’ memorial but a memorial to the nation’s tormented experience with the entire war.

“Throughout this time,” she said, “I was very careful not to discuss my [political] beliefs. … I played it extremely naïve about politics, instead turning the discussion into a strictly aesthetic one.”

On July 7, 1981, the US Commission of Fine Arts, the agency charged with approving public artworks in the nation’s capital, held its first public hearing on the Vietnam Memorial. Its presiding chairman was J. Carter Brown, a formidable figure in Washington and a Rhode Island patrician whose family traced its American roots back to the Revolutionary War and was responsible for the initial endowment of Brown University in Providence. His father had been an assistant secretary of the Navy. After a stellar career at Harvard and study in Florence, Italy, with the legendary art historian Bernard Berenson, Brown became the director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington when he was just thirty-four years old. In that post, he would supervise the building of the gallery’s groundbreaking East Wing, designed by I. M. Pei, and preside over spectacular King Tut and Thomas Jefferson exhibitions. He was also the longest serving leader of the US Commission of Fine Arts, from 1971 to 2002.

The director’s judgment and appreciation of artistic merit was refined. Around Washington Brown was a leading public intellectual, a familiar figure on the social scene, always elegant and thin in his English suits, and noted for his charm, courtesy, and savoir faire. Sometimes called America’s art czar and the country’s “arbiter of excellence,” it was said that if the United States had a minister of culture, J. Carter Brown was the ideal choice. Unlike other Washington dignitaries, Brown always looked good in white tie and tails.

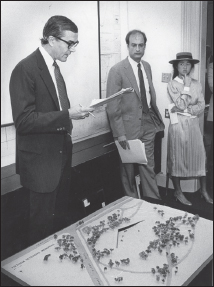

J. Carter Brown and Diana, Princess of Wales, National Gallery of Art, 1985

At the hearing, Paul Spreiregen addressed the commission first, speaking of the competition and then of the winning design. It had no precedent in public art. He praised its absence of a representational symbol. “A symbol,” he said, “would tend to arrest thought rather than to arouse and expand it.” And then the microphone was turned over to Maya Lin.

Instead of some new defense, she chose simply to read her soaring, compelling description from her submission. Somehow, spoken in her soft voice rather than absorbed on a printed page, her words were even more magical. The rift in the earth … the long, polished stone wall … emerging and receding. … The metaphor was riveting, and the panel was mesmerized and amazed at this astounding result.

Lin was thrilled by the hearing. “Fine Arts went superbly,” she wrote in her journal. “It was reassuring, elating, i like my work to be liked, what would happen if it were criticized by intelligent people? people i respect? would i feel wrong or wronged, am i arrogant in my personality and in my work … [people should] lift their eyes up to the magic right within their reach, the joy felt in making something that flows from reason to reality.” Then she added the word “burp.”

Predictably, the hearing contained one sour note, the first adverse public testimony against the design, a spark that would soon burst into a raging flame. A translator and radio operator named Scott Brewer, whose Vietnam duty had been in Saigon and Bien Hoa, stepped forward as the first public detractor. Lin, wearing a porkpie hat and long skirt, stood to the side, listening intently. Countering the lavish praise of the design, Brewer found it to be “abstract, anonymous, inconspicuous, and meaningless, and it is so unfulfilling as a lasting memorial that no memorial would be a better alternative.”

Robert Doubek and Maya Lin listen as veteran Scott Brewer, left, pillories Lin’s design before the US Commission of Fine Arts, July 7, 1981.

But Brewer’s criticism was a mere hiccup in the air of congratulation and did little to mar the day. After praise was heaped on Lin for the design, Brown had the last word. “Nobility … is the great hallmark of this design,” he said in his sonorous voice. Pointing to the design’s deference to the nearby the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial, he continued, “It is an understatement of sensitivity … and is highly commendable … we give the Commission’s blessing to the jury and to the designer.”

The public battle was just beginning.