A KIND OF OCEAN

After Frederick Hart was commissioned to provide a suitable sculpture to complement Maya Lin’s wall, he would muse to his wife and model, Lindy, about his dreams for the work. The Renaissance was his ideal, as much for the philosophy of the artists as for their virtuosity of technique. Then, unlike now, he felt, art was not an end in itself but a form of service. The art that graced the plazas and the churches of sixteenth-century Italy embraced the values of the common man, as well as his religious beliefs, history, and ideals. Sculpture was, in Dante’s words, “visible speech,” and the artist’s dedication to service gave art its “moral authority.” In ancient Greece as well, Hart believed, there was no distinction between aesthetics and ethics.

“Works of art achieved greatness by embodying great ideas,” he would write later.

For the uniforms of his soldiers, he planned to emulate the exacting detail of the Italian Baroque master Gian Lorenzo Bernini, especially the flowing drapery of Bernini’s alabaster angels that grace the Ponte Sant’Angelo in Rome.

“I want to make Bernini’s angels weep,” he told Lindy.

With so lofty an idea of his calling, the sculptor found himself somewhat paralyzed at first, when, amid the nasty contention and the notoriety Maya Lin was enduring through the spring and summer of 1982, he contemplated the task ahead. By midsummer, however, he finally got under way. At this point he did not resent all the attention accorded to Lin, nor did he mind that his work was being labeled as “the compromise statue,” for he needed quiet space to work and concentrate. In visualizing his three soldiers he first needed to imagine the composition and proportions of the grouping. The easy part was the correctness: a Hispanic machine gunner, an African-American infantryman, and a white platoon leader with his men. Then the mood: camaraderie, youth, vulnerability, wariness, exhaustion, dirt, sweat, and amazement as the figures gazed upon the magnitude of loss spread out before them. Then the gear and the garments in the style of Bernini. But the faces would be everything. He would reach for expressions that would make the viewer wonder what each soldier was thinking, so that the veteran could associate his own experiences in Vietnam with the figures. The goal would be for the surviving veteran to enter himself into the sculpture itself.

Quietly turning aside the pressure for a heroic sculpture, a mantra developed in his imagination: his soldiers were not fighting for their country but for each other.

In early September, two months before Maya Lin’s wall was dedicated, Hart invited his patrons to view his progress. As Jan Scruggs and the board members of the Fund arrived at his studio, their eyes fell first on Hart’s larger plaster works: the figure of Adam that was headed for a prominent niche at the Washington National Cathedral, an unfinished sculpture of St. Peter, and a triangular scale model of Ex Nihilo. In the middle of the floor was a headless mannequin dressed in full combat gear. As they entered, Scruggs’s group was gossiping. Was Maya Lin really going to sue the Fund for breach of contract?

“I don’t think she’ll sue,” one of the veterans was saying. “It would be a very bad step for her professionally. And we could bring a lot of heat on her if she did.” It was clear now whose side they were on. They chortled when someone remarked on what a difficult person Lin was. She was not accustomed to “assertive restraining,” someone quipped.

They then approached Hart’s clay model for their first look. In Hart’s view, he was presenting a sketch, a first draft. The maquette stood only 17 1/2 inches tall, and the visitors had to imagine what it would look like when it was larger than life, at about seven feet tall. Hart was still struggling with certain aspects of the piece, especially the face of the black figure. When his agent admired the angry expression on that soldier, Hart scowled. He was going for anguish, not anger. The body was okay. He had used a regular at his favorite Dupont Circle bar, Childe Harold, as the model. But the face was wrong. A few days later he would slice off the angry visage completely and start over. The face of the Hispanic soldier was more satisfactory. Beneath a bush hat, that soldier carried a machine gun on his shoulders, and now Hart told his guests:

“I always thought of a machine gunner as a tough, bulky, rough-and-tumble type. But I wanted to make this figure the youngest-looking and most innocent, so you get the contrast between his youthfulness and the ferocity of the weaponry. In the juxtaposition of those two extremes, you get some poetry.”

The session showed how comfortable the artist had become in the company of veterans, and how much, by this time, he identified with their experiences, despite his 4 F deferment and his time on the protest lines. His patrons loved his concentration on the details, the veins in the hands, the bullets in the bandolier, the multiple canteens they carried, the towel over the neck of the black soldier, carrying his helmet behind him.

“That’s a guy I’ve met,” said one of the veterans.

“You wonder what he’s thinking, what he’s seeing,” said another. “You’re invited to make up a story that fits with him, and that’s what makes it a work of art.”

Still another noticed that Hart had placed a dog tag on the boot of one figure, and this led to a discourse on dog tags in general, how they were often taped over when the soldier went into combat, and how sometimes platoon sergeants suggested to his troopers that they duplicate the tags in both boots. If his head was blown off, the sergeant advised drolly, the tags might be lost, but the odds were less that both feet would be blown off at once.

Couldn’t the sculptor put a serial number on the tag? someone asked.

“I’m not that good,” Hart chuckled.

“Then what about blood type?”

In the days that followed, the problem of the black soldier’s unsatisfying expression was solved in a fortuitous way. In a waiting room of a hospital where Hart had gone to visit a sick friend, he encountered an African-American mother with her seventeen-year-old son. With his full forehead and dreamy expression, the teenager had just the face he wanted. That was it! Hart recruited the boy to be his model.

—

As the Art War over Vietnam memorialization moved into its fifth year, it appeared in the early days of 1983 that there was peace at last. Maya Lin’s wall was built and dedicated. The Commission of Fine Arts had accepted a compromise to add a sculpture and a flagpole to the memorial. Suitable language had been found for an inscription that honored veterans without glorifying them or their war. Frederick Hart’s statuary had been conceived, and a model had been found worthy. In its October 13 meeting the previous fall, the Commission of Fine Arts had settled on the placement of the statue and the flag as an “entrance experience.” It remained only for the statue to be finished, approved, and installed.

Hold on.

When Congress came back into session in January, the efforts of ex-Congressman Don Bailey to legislate the location of the flag—immediately above the junction of the walls and to place the Hart statue directly in front of the vertex—acquired new life. This became known as the “Bailey option” even though he was no longer in Congress. A congressman from California, Duncan Hunter, who had served in the 75th Rangers in Vietnam, took over the mission and urged the public to pressure the commission. Of course, any new legislation that might be introduced would require time-consuming congressional hearings. That, wrote Washington Post columnist Philip Geyelin, was likely to rekindle the war “in a mindless and impassioned way.”

The Bailey Option

Jan Scruggs and his cohorts reacted in horror. By this point the aesthetic arguments exhausted them, and they were ready to go with virtually any option for the placement of the flag and sculpture, so long as there was no further delay in completing the memorial. Indeed, by this time, it seemed as if only the commission still cared about aesthetics … and it was the commission that would have the final say.

Inspired by the diehards in Congress, Secretary James Watt jumped back into the fray with full-throated support for the golf hole alternative. “This so-called Bailey option for placement of the statue and flag staff fully meets the commitment we made to reach a compromise on this issue,” he wrote in a letter to the relevant government agencies. In a speech to the US Chamber of Commerce, Watt threatened to stall the completion of the memorial until a consensus developed on the location issue. That could take up to a year. “It’s a memorial and a monument to those who lived and died for America, and it’s a political expression,” Watt told the chamber. “It’s not an expression just of the arts community, although it includes them, and so I would expect that [the matter] will be resolved within the next twelve to fifteen months.” The Memorial Fund expressed its shock at this renewed interference from the political world. Philip Geyelin wrote that if Watt did what he said he was going to do, the rift over Maya Lin’s design would make the wounds of Vietnam even worse.

The next meeting of the Commission of Fine Arts was scheduled for February 8, and as the date got closer, Secretary Watt seemed to relent slightly, acknowledging the commission’s authority, dropping his threat of delay, and expressing the lame hope that the commission would “not overlook the feelings of the Vietnam veterans in consideration of aesthetic and architectural concerns.” All hoped that the commission would lay this last issue to rest. The political noise in advance of the meeting did not quiet, however. Congressman Hunter released a statement denouncing Kent Cooper’s characterization of the flagpole as a “long stringy object.” Said Representative Hunter: “The veterans never considered the flag ‘a long stringy object,’ and I can guarantee that the families of the individuals whose names are inscribed on the memorial walls don’t think the flag is a long stringy object.”

And yet, as the commission convened before a packed crowd the following day, when a scale model of a fifty-foot flagpole was placed immediately above a scale model of the wall, it did, indeed, look like a long stringy object. The proximity of flagpole and wall was palpably absurd, which was appreciated by all except Hunter and Bailey. “Pure aesthetics” is not the only consideration, Hunter complained, and rested his case for the Bailey option, producing a threadbare press release from the Warner meeting that seemed to support his apex positioning. Very quickly, J. Carter Brown pointed out that the commission was not a party to that compromise, and only it could make the aesthetic determination. No ad hoc congressional gathering held any sway here. He was very glad, the chairman said, that the country was “governed by laws and not by press releases.”

The usual suspects testified in the usual way that day, and there was the familiar bickering back and forth about the flag and the Hart sculpture. “This baloney has gone on long enough,” Jan Scruggs groused. By this time, he had come to view his fiercest opponents, Webb, Carhart, Copulos, and company, as “evil” men. “The Vietnam Veterans Memorial was a Rorschach inkblot,” Scruggs would write later. “Right-wing Vietnam War Defenders saw the Hand of Satan emerging as a two-finger peace sign on the Mall dishonoring America’s sacred dead as it honored communist victory.”

It was left to Hart himself to make the convincing and conclusive case. The artist had acquiesced in the idea that his prized statue would be placed at the tree line, not exposed and lonely in the open ground of the knoll across from the wall. A careful plan had been worked out between himself, his landscaping colleague, Joseph Brown, and Cooper, the architect of record, that treated Maya Lin’s design with “the utmost reverence” while providing emphasis, coherence, and prominence to each of the elements. The commission should vote for it.

After the vote, J. Carter Brown announced the verdict. By placing the statue and the flag at the intersection of pathways as an entrance experience in a copse of trees, the plan would give “maximal prominence” to the American flag. It would be a “rallying point” for visitors who came to visit the wall. Positioning the statue away from the wall would make it stand alone—he did not use the word “naked” this time—and complement rather than compete with the wall. The landscaper Brown put the concept differently. This final design would create a soft, ushering outdoor room.

Still, something was left to Lin’s opponents. On the flagpole pedestal, the inscription read: “This flag represents the service rendered to our country by the veterans of the Vietnam War. The flag affirms the principles of freedom for which they fought and their pride in having served under difficult circumstances.”

There was a footnote to this denouement of the Art War. Toward the end, there was a surprising witness who was not there to talk about flagpoles, inscriptions, or statues. Historian and psychologist Dr. Steven M. Silver was treating veterans suffering from PTSD. He had been a Marine fighter pilot in Vietnam, flying numerous combat missions in 1969 to 1970.

Straying from the specific issue at hand, Dr. Silver told the commission of the value in taking his patients to visit the wall. Nine years after the end of active combat, he said, “It is virtually a cliché to state that the American people have gone through a period of repressing their country’s Vietnam experience. … In their agony and trauma, the people of this country tried to ignore reminders of the war. … We are beginning to see an end to this repression. … As the repression ends, the buried thoughts and feelings come boiling, sometimes exploding, to the surface. Whether taking place on the individual or the national level, such surfacing can be painful, terrifying, exciting, joyous, or cathartic—above all, it is necessary.”

Dr. Silver did not choose sides between Lin and Hart but applauded both for their value to the tormented Vietnam generation. Lin’s design was effective in eliciting these buried feelings, not only for his PTSD patients but for all Vietnam veterans as well as the dissenters, precisely because the wall did not interpose an image on the viewer. And Hart’s soldiers were important for those veterans in need of “specificity.”

However, something he wrote beforehand to the Memorial Fund was far more memorable than his psychologizing. He proposed a Constitutional amendment that would read: “Before any President may commit American forces to combat, and before any member of Congress may vote on a declaration of war, said President or member is required to read aloud the names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.”

After the commission’s decision, Frederick Hart separated himself from the turmoil. He had hit his stride. He knew what he was doing and where he was going. He had heard the slurs: his work was trite or stale, his figures mere cartoon characters, reminiscent of a Hallmark card or GI Joe toys. Much of the criticism came from people who had only seen pictures of his sketch. When they saw the finished product, he was sure, he would be vindicated.

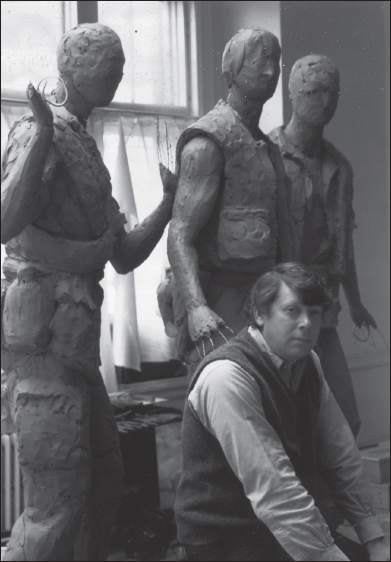

Frederick Hart with the maquette for The Three Soldiers

An armature had been built for each figure, and a seven-foot-long block of clay stood before him. Marines from the Capitol Hill barracks were serving as models. It was time to give the faces of his soldiers life and character. The real sculpting had begun. As his wife Lindy would say, it was time for the poetry and the music. It was time to make them sing.