THE NOISE OF YOUR SONGS

“Nothing sublimely artistic has ever arisen out of mere art, any more than anything essentially reasonable has ever arisen out of pure reason. There must always be a rich moral soil for any great aesthetic growth.”

G. K. Chesterton

The careers of Maya Lin and Frederick Hart continued to soar after the Art War, but no matter what fine, memorable work they produced in the coming decades, their reputations would forever be defined by their struggle to design and to consummate a national memorial for the Vietnam War. It may have been harder for Lin than for Hart to overcome the shadow, since her astonishing achievement in Washington had come such an early age. How was she ever to top that? Her situation reminded me of the remark that Russell Baker, the wise and witty New York Times columnist, gave to me when I published my first book, a Vietnam-generation novel titled To Defend, To Destroy, in 1971: “I wish you success, but not too much.”

After graduating from Yale, Lin pursued a master’s degree in architecture at Harvard University, splitting her time between her studies, her often contentious consultations with Kent Cooper, and her gritty public defense of her masterwork. The stress of balancing these daunting challenges took its toll, as she was briefly hospitalized in Boston with nervous exhaustion. It was said that at Harvard she became more open to criticism, and in her public appearances, she had visibly matured. If she was often in the library, she was also frequently on national television. She was fast becoming one of the most admired women in America. She completed her master’s degree in architecture back at Yale, where in 1987 she was awarded an honorary doctorate.

She went on to design other memorials, two of which were, for more discrete audiences, just as important, as elegant, and as moving as the Vietnam Memorial. The first was her commission to design a civil rights memorial in Montgomery, Alabama. This time there would be no competition, for the driving force behind the idea was the dynamic founder and director of the Southern Poverty Law Center, Morris Dees. Eddie Ashworth, a colleague of Dees at the center, simply called her up and gave her the job.

As with the Vietnam War, Lin had scant knowledge of the civil rights struggle of the 1950s and ’60s. She was too young to know about the movement that transformed America; that history was barely mentioned in her cloistered schooling in Athens, Ohio. This ignorance did not bother Dees and Ashworth. They too were operating on instinct. By this time her artist’s creative process was clear in her mind. She needed to define for herself what the essence of the entire historical saga was, to strip it bare of its details and noise, and get to the heart of the revolution. Only then could she begin to design a concept. But what was the essence?

Lin took three months to research the history, but it was only on the plane ride down to Alabama that she read Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech and came upon King’s invocation of the biblical passage from the book of Amos, which reads in full:

Take away from me the noise of your songs;

to the melody of your harps I will not listen.

But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like a mighty stream.

She knew instantly that the memorial had to have water as its central, unifying element, water that could bind together the events of the movement and the forty martyrs of the struggle like Emmett Till, Medgar Evers, and Jimmie Lee Jackson, whose names were to be carved on the monument. The names had to be joined to the events in which they were involved, as cause and effect, creating a timeline of the movement, to show how these lost heroes of the struggle helped to change history.

The result was a circular black granite table—black again—from whose center a thin veneer of water flows evenly across the surface. From the center, lines are carved in the stone to radiate outward as names and seminal events were intertwined. Like the Vietnam Memorial, the visiting pilgrims could touch the names and the events and feel the water that binds everything together. For the participants in the struggle, like the veterans of the Vietnam War, the mere touching was meant to trigger memories and bring the monument alive. At the 1989 dedication of the monument, Rosa Parks touched her name and watched how that touch changed the flow of the water, as if somehow her story might have been different. Behind the table as its backdrop is a high black granite wall in which a portion of the line from King’s speech is carved in large bold letters (unlike the nearly invisible epigraph at the Vietnam Memorial). King’s words paraphrased and embroidered the Amos passage:

We will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

As if she was channeling her Vietnam Wall experience, Lin would describe her vision of the plaza as “a contemplative area — a place to remember the Civil Rights Movement, to honor those killed during the struggle, to appreciate how far the country has come in its quest for equality, and to consider how far it has to go.”

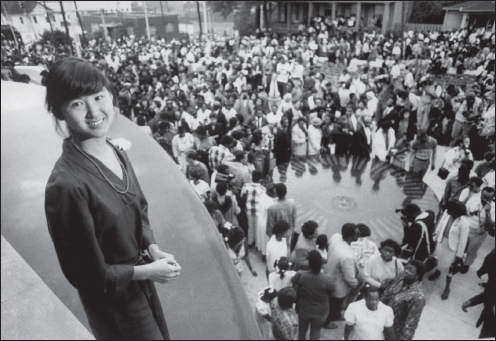

Maya Lin at the dedication of the Civil Rights Memorial, Montgomery, Alabama, 1989

Her second significant memorial was her Women’s Table (1993) that the president of Yale University commissioned her to design in commemoration of the twentieth anniversary of coeducation at her alma mater. Again, as Lin contemplated the essence, she enlarged the idea and came up with the unexpected. What emerged was an egg-shaped granite table with a fountainhead at the center from which, like the civil rights memorial, a thin layer of water flows across the surface. Spiraling outward from the center, nautilus-like, lines denoting years were cut in the surface, not starting in the celebratory year of 1969, but rather in 1701, the year the university was founded. At the end of the lines near the edge, simple digits denote the number of female students at the school. From 1701 to 1873 the number is zero. From 1873, the numbers are low for the few female students who were allowed into the nursing program or the School of Fine Arts. This implied criticism of the way in which women were barred from higher education for 265 years at one of the country’s most prestigious institutions did not sit well with everyone. A feminist scholar likened the structure’s womb-like shape as well as its sense of procreative flowing water.

After 1995 Lin made the environment her passion as she considered how people view landscapes and relate to the natural world. In her environmental installations, she was driven, she would say, by “a simple desire to make people aware of their surroundings, not just the physical world but also the psychological world we live in.” After cutting a rift in the earth that symbolized the rift in the Vietnam Generation, she has produced a number of environmental earthworks that shape and mold the landscape in startling ways. The job of the artist, she professes, is to say something new and not quite familiar. Among those works are her aerodynamic wave fields in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Storm King Mountain in New York, where man-made, parallel earth mounds suggest ocean waves … or piles of glass beads shaped to suggest mountains or the Chesapeake Bay. There have been more strictly architectural projects as well, including the Langston Hughes Library and Riggio-Lynch Chapel in Clinton, Tennessee, the Weber House in Williamstown, Massachusetts, with its wavy roof that mimics the hills in the distance, and a renovation of the Smith College library.

The artist wanted to counter the fixed notion of a memorial as a mark on the ground. She founded a memorial that was to be without form. Called “What Is Missing?” it is a Web-based celebration of the natural world: what it is now, what it used to be, how wonderful the things are that remain, and how many wonders have been lost. Employing videos in an interactive multimedia format, the cyber-memorial is meant to be an “ecological history of the planet,” paying special attention to extinct species and disappearing places in what is called the “extinction crisis.”

In 2000 Lin published her first book, Boundaries. “I feel I exist on the boundaries somewhere between science and art, art and architecture, public and private, east and west,” she wrote. “I am always trying to find a balance between these opposing forces, finding the place where opposites meet.” In 2009, she was given the highest American award an artist can receive, the National Medal of Arts. And in November 2016 President Barack Obama presented her with the country’s highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. She looked a bit sheepish next to two other recipients, Kareem Abdul Jabbar and Michael Jordan. Obama invoked Lin’s own phrase, “physical acts of poetry,” adding that her work reminds us “that the most important element of art and architecture is human emotion.” When the president mentioned the B+ she had received in Andrus Barr’s architecture class at Yale, laughter filled the room. What must be the most famous undergraduate grade in the history of higher education had finally become the grist for a presidential joke.

Maya Lin receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama at the White House, November 22, 2016

Through these decades of immensely productive and varied work in architecture, art, and landscape design, Lin has grown weary of talking about the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, afraid of the age-old curse of being typecast. (She would turn aside a number of requests to build other monuments, not wanting to be known as a memorial “specialist.”) Routinely, she explains to interviewers that she will not discuss that painful yet triumphant chapter of her life. But the shadow will not go away. In a conversation with a Xin Wu, a professor of art history at William and Mary University, she was asked about her activism in the environmental movement and more broadly about her attitude toward the artist’s role in world affairs.

“I supposed it has changed quite a bit since the Vietnam Veterans Memorial twenty-seven years ago, now that you are more mature and certain of yourself,” Dr. Wu prodded.

“I think I was less mature but more sure of myself then,” Lin replied. “As you get older, you get more reflective and possibly question more. What protects you when you are young is the belief that you are right. There is a naivety of youth. One loses that naïve certainty when getting older. You understand that life is more complicated.”

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the largest commission in history for a memorial followed, and in the opinion of Martin Filler, the distinguished historian of architecture, Lin could have had for the asking the job to design it. Instead, she agreed only to be on the jury which, in the end, would consider 5,201 entries, more than four times the number of submissions as the Vietnam memorial jury had judged. The eventual winner of the World Trade Center memorial competition, Michael Arad, was a thirty-four-year-old junior employee in a New York City municipal office, and like Lin, Arad had an enormous amount of success at a very young age. His original concept called for two gigantic sunken pools whose measurements comported to the footprints of the fallen twin towers; to complete the emotion of grief and identification, visitors would be allowed to descend into the abyss below the cascading water. But in the contentious eight years it took to realize the memorial, the possibility of descent below the waters had to be scrapped. Once again, the essence of the final design was the combination of victims’ names engraved in black granite and a non-representative work of art where the emotional reaction to the piece was left to the individual viewer. To Filler, Arad’s work reaffirmed Maya Lin’s “radical reconception” of memorialization with her Vietnam wall.

The Vietnam Women’s Memorial (1993) by Glenna Goodacre

“The test of time has already proven the validity of Maya Lin’s insights into the wellsprings of mourning in the modern age,” he wrote.

The 1990s was a political period for Frederick Hart, when he was at the peak of his international fame and the controversy over his soldiers had largely subsided. He sculpted figures that drew upon his Southern roots and his political proclivities. His statue of former US president and Georgia governor Jimmy Carter had been placed on the grounds of the state capital in Atlanta. His stolid rendition of Richard Russell, the Georgia senator and towering legislative hawk of the 1960s, graced in the grand rotunda of the Russell Senate Office Building in Washington, DC. He had completed his head-tilting, smiling bust of the ferocious segregationist icon, Strom Thurmond, for the Strom Thurmond Room in the US Capitol and finished a bland bust of former vice president Dan Quayle.

Much more important at this time, though, were his purely artistic sculptures that reflected his range, his imagination, and his spiritual longings, which did far more to burnish his reputation as an important American artist. His bronze and Lucite pieces in limited editions made him a wealthy man. Through the 1990s the sculptor had developed a unique process of transforming a clay model into an ethereal image that would be embedded in clear acrylic resin or Lucite. He called his first efforts in this new medium his “creation series” and his “dream series”; memorable in this collection was an unrealized piece, Heroic Spirit that was proposed for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. In 1997, he finished his extraordinary Cross of the Millennium. Commissioned by St. Vincent de Paul Catholic Church in Andover, Kansas, the altarpiece featured the willowy, other-worldly figure of Jesus Christ appearing to float within the plastic cross. Lit with soft light from below, Hart called it “sculpting with light.” In May of that year when he presented the cross to Pope John Paul II at a Vatican ceremony, the pontiff said to him, “You have created a profound theological statement for our day.”

But perhaps his most impressive work during this period was his Daughters of Odessa, depicting the four Romanov daughters of the last Russian czar, Nicholas II, who were assassinated in 1918. This lovely, sensual grouping of youthful, energetic figures, draped in willowy gossamer gowns, reflected his fascination with Russian history. He called it an allegorical work, “an elegy in bronze which is dedicated to the memory of all the innocent victims of the twentieth century.” A bronze of this moving work ended up in the private garden of the Prince of Wales at Highgrove House, England, along with his bronze bas-relief of Lord Mountbatten that Prince Charles had commissioned.

Chesley, the Virginia country estate of Frederick Hart

Unapologetically, the artist reveled in his reputation as a “classicist,” even as a segment of the modern art world continued to heap scorn on his work. A former New York museum director would call him an “art fascist,” and a critic for Art in America—a sculptor himself—labeled Hart’s commercial pieces as “kitsch.” “Everything is so conventionally handled—I find them appalling,” he complained. Resentment abounded at his financial success, his sophisticated marketing acumen, and his lavish, country squire lifestyle. If his antebellum mansion, Chesley, was a throwback to a prior century, Hart embraced the feeling. A love of grandeur reflected a “sense of the heroic,” he remarked. “The idea of the heroic life, especially in artistic terms, has always been one of my personal myths.” Wryly, he described Chesley as a “revival of a Beaux Arts Revival of Greek Revival” and a “landmark of reactionary architecture.” It was there, he said, that “I’m doing things that just haven’t been done in a hundred years, like using huge amounts of highly ornamented plaster, lots of faux marble, the statuary and the big murals—Who else does that kind of thing?”

During this high-flying period, however, trouble emerged. In October 1997, Warner Brothers released Devil’s Advocate, a big-budget movie starring Al Pacino as a sleazy New York lawyer who is supposed to be Satan himself. The climactic scene ushered the viewer into the devil’s chamber, decorated as if it were a New York penthouse, with cathedral ceilings, heavy wood paneling, panoramic windows, and a huge platform desk. This becomes the tableaux for a crude sex scene and gory suicide. Behind the desk a huge white frieze featured naturalistic naked, marbled figures, frozen in the maw, the maw of creation. The action gets hot and heavy when the devil tries to force his son (Keanu Reeves) to have sex with a temptress (Connie Nielson)—her name is Christa Bella, a play on the words beautiful Christ—in order to create the Antichrist. During the devil’s pitch, the naked figures in the frieze behind him come alive and begin to writhe lasciviously, erotically toward one other.

The frieze was Hart’s Ex Nihilo.

This scurrilous debasement of religious art into profane art was astonishing, and it soon became clear that the filmmakers had simply placed Ex Nihilo on a computer template, removed one figure, and then manipulated the figures into suggestive motion. That a work of sacred art could be so blatantly misappropriated, vulgarized, and transformed into pornography without consequence was totally unacceptable. It raised the question, ironically similar to the complaint of Maya Lin with the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, about the inviolability of an artist’s work and that artist’s moral rights to protect the work from infringement.

Within days the National Cathedral joined Hart in a lawsuit against Warner Brothers for copyright infringement. In a statement the cathedral hierarchy said that it “considers all objects of art and iconography depicted on or in the cathedral as sacred objects intended to convey God’s immanence and presence in the world.” In short, the west entrance of the cathedral had been debased and demonized.

During sessions at US Federal Court over the case that winter, the strain on Hart was wincingly visible as he obsessed over the details, even as the case seemed to be going his way. Early in 1998, the presiding judge warned Warner Brothers that if the studio did not settle the case promptly, he would immediately halt the distribution of 400,000 videotapes of the movie. At this, the studio collapsed, agreeing to pay several million dollars in damages, to turn the faux Hart backdrop to white spaghetti in future syndications of the film, and to attach a disclaimer to the cassettes or pay-for-view screenings disclaiming any relationship to Ex Nihilo.

As the case took a turn toward Hart’s favor, he had a stroke that impaired the right side of his brain, paralyzed his left hand, and defeated any effort to sketch or even to stabilize his clay. Nevertheless, he would drag himself to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial one last time on May 31, 1999—Memorial Day—for his last words on the controversy. “Public art can serve no higher purpose than to reveal and embody the nobility of the human spirit such as that exemplified by the Vietnam veteran’s dedicated service to his country.” He died ten weeks later. He was fifty-six.

On August 18, 1999, a celebration of his life and work was held at the imposing cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in downtown Washington. On the altar, bathed in light, was his luminous Cross of the Millennium. Among the formal celebrants were two individuals who had been central to his spiritual life and his artistic success. One was Reverend Stephen Happel, who had shepherded him through his conversion to Catholicism in the 1970s. The other was J. Carter Brown, the former director of the National Gallery of Art and chairman of the Commission of Fine Arts. It was Brown, more than anyone, who brokered the deal to join Maya Lin’s wall with Hart’s three soldiers.

In 2004 President George W. Bush presented the National Medal of Arts to Frederick Hart’s widow, six years before Maya Lin received the same medal.

The artist surely knew that his legacy would not be his luminous acrylic cross or his Ex Nihilo or his Daughters of Odessa. It would rest on his three soldiers. Massive reproductions of their faces embellish the sides of tourist buses that roam Washington’s memorial-filled center city. There is often a clutch of people who gather around the Hart soldiers with its exquisite detail before they enter the pathway to the wall and join the others who are contemplating the enormity of the Vietnam conflict.

—

Of the other players in this saga, Maya Lin’s chief antagonists—Jim Webb and Tom Carhart—spurned repeated invitations to reflect on their campaign against the wall, especially as to whether, in light of the memorial’s universal acceptance, they had any regrets. From their silence, we are left to draw our own conclusions. The guru of the grand competition, Paul Spreiregen, would, by contrast, continue to think and write extensively of his pride in the fairness and professionalism of the competition he ran and his joy in the final result. “To put art in the service of memory,” he wrote, “is an ancient ritual of the tributary giving of its most valuable resource, thus its highest honor.” He also wrote of his disappointments. With a competition so emotional and fragile, he felt that both Lin and her opponents came very close to undermining the entire enterprise. The veterans’ opposition was at times vicious and underhanded, and at other times, highly effective. It nearly succeeded. But years later he still harbored a special resentment for Lin. He deplored the mythology that he felt had grown up around her. He had found her naïve and antagonistic behavior destructive from the start, and he kept detailed notes on her incessant complaining, which he saw as subversive. To his credit, however, despite his personal animus, he unfailingly supported her design as the best and wisest choice. He had fought bravely and eloquently for its integrity. “If the flagpole and the statue were to disappear this afternoon,” he wrote, “the [memorial] would not lose an iota of its power.” If he had any qualms at all about the design, he wished that the memorial had been more constructive and “life-giving.”

“I wish the effort had been to make a better plowshare rather than to bury a sword.”

—

For me, like so many others, that walk down the cobblestone pathway is personal. Down the slope, my image is reflected in the blizzard of names, past the low point at the vertex and then up the slope to Panel 35E where the name of my one comrade in arms is etched.

US postage stamp issued January 12, 2000