I was one of those who took advantage of a loophole in the early years of the Vietnam conflict. The US secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall, had hired me straight out of college as a researcher for his seminal book about the history of American conservation called The Quiet Crisis. Eventually, I became his speech writer and remained with him in a singularly blessed association for fifteen months. During that period, the secretary had protected me from being drafted by writing to my draft board and asking that I be deferred because of important government work. I left him in September 1964 to take a job as a reporter for the Chicago Daily News. Like so many guardians of Vietnam-era youth who professed reasons to keep young men out of harm’s way, Udall renewed his request for my deferment, claiming that he needed to use my services in connection with “a number of vital problems in the field of conservation.” Of course, this was a lie. And so, for more than a year as the Vietnam conflict began to heat up, I lived my own quiet crisis of guilt over my fake deferment.

On July 28, 1965, at a news conference in the East Room of the White House, after he committed the first American combat units to the Vietnam conflict, President Lyndon Johnson announced an immediate increase in troop strength from 75,000 to 125,000 and doubled the monthly draft call to 35,000. “This is a different kind of war,” the president said. “There are no marching armies or solemn declarations. … But we must not let this mask the central fact that this is really war. It is guided by North Vietnam, and it is spurred by Communist China. Its goal is to conquer the South, to defeat American power, and to extend the Asiatic dominion of Communism. There are great stakes in the balance.”

Conscience-stricken, I felt I could no longer hide behind Udall’s largesse and my own hypocrisy. I was not truly or sincerely a conscientious objector. For better or for worse, I wanted to participate fully in the experience of my generation and succumbed to the infectious allure of national service and masculine testing. On September 27, 1965, I enlisted for a three-year hitch in US Army Intelligence. And that led to a different quiet crisis. As the war raced toward its peak of violence, I was deployed first to Baltimore for intelligence training, then to Monterey, California, for a year of Japanese language training, and finally, to an Intelligence Headquarters Unit in Hawaii. Conflicted between joyful relief and a tinge of regret, I was missing out on the war.

Things could have gone very differently for me. On Maya Lin’s wall, I have one friend. His fate does have something to do with a battle and even a war, won or lost.

Ronald E. Ray

His name was Ronald Edwin Ray, but in Vietnam his cover name was Mr. Reynolds. He was a stocky, jovial, athletic native of Spokane, Washington, American to the core, a football player and class president in high school, an indifferent political science major at Washington State University, for whom military service afterward was just the next natural step. He was neither for nor against the war. I can’t recall ever having a political discussion with him when we bunked next to one another at Fort Holabird, Maryland. Unlike me, he had no thoughts about the dilemma of his generation or about the question of engagement or detachment from his country’s cause. Nor was he a romantic like me. He was a genuine, uncritical friend, and I liked him immensely. He covered for me at morning musters when I slipped away overnight to Washington, DC, against regulations.

Like me he had volunteered for army intelligence. By opting for an extra year in the service, we thought we could exercise some measure of control over how we “served our country.” By agreeing to that third year we made an honorable contract with our government—a notion so alien for a later generation of soldiers that endured multiple deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan—and avoided the fate of the draftee on the front lines. We could also focus on the somewhat glamorous training for recruiting foreign agents for dangerous missions. If, God forbid, we were sent to Vietnam, by law the tour could last for only one year.

After our training in Baltimore, as I went off to California, he was ordered to a small headquarters unit on Ford Island at Pearl Harbor. A year later, I too got orders to the same unit in Hawaii and was stunned to hear that Ron had left and was in Vietnam. What had happened? I wondered. Why on earth …?

—

It was a perfect afternoon for a parade in the fall of 1983 when I left the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and crossed the Potomac River to Arlington National Cemetery. The air was crisp and clear, after a morning rain, and the white marble of the amphitheater sliced across the dazzling blue of the sky. The Veterans Day ceremony was to be held in a copse of dogwoods. Already the Air Force band had assembled, lounging about, flaccid, middle-aged musicians poured into ill-fitting costumes. The honor guard was rehearsing its slow approach to the viewing stand.

I was early, and Ron’s mother still had not arrived, so I wandered away, down Sherman Drive to McPherson Drive. It was a strange way to get to a Confederate monument. Moses Ezekiel, a Virginian who fought in the Battle of New Market in 1863, had sculpted the Southern tribute, a gift of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, as a testament to the Lost Cause and to the sacrifice of the Southern soldier. Towering high upon a circular pedestal, there upon the back ridge of the vast cemetery, thirty-two feet in height, crowned with olive garlands, the heroic figure of a woman looks down sorrowfully on the Southern graves. Facing south, she holds out a laurel wreath in love and resignation. Below her a circular bronze frieze depicts poignant scenes. Strapping men comfort hoop-skirted ladies on their departure, and harried, plainly dressed women comfort raggedy men on their return. Time had poured green rivulets from the bronze over the stained white marble. Time would not corrode black marble, I thought.

Back at the amphitheater Mrs. “Reynolds” broke away from a covey of care-worn ladies. The day before, when she wore a black sweat shirt, sequined with a sparkling American eagle clutching a Star-Spangled Banner above the words “Vietnam Heroes,” she had given me a copy of Ron’s Bronze Star citation. Now she was resplendent in white, her immaculate wool suit and white military cap held perfectly in place with bobby pins. In the lapel of her jacket a lovely piece of jewelry, a demure gold star set upon a blue background, completed her look.

She gave me a program, and we chatted about her week in Washington. She was a woman of few words, and they were delivered in the smoky flat tones of the Arkansas rice country from which she hailed. She had been cautious with me. Her volunteer work in veterans’ hospitals embraced her son’s heroism. She harbored no bitterness, although she had encountered the bitterness of other Gold Star mothers countless times. Once in Spokane, she had invited forty-three mothers to tea, and no one accepted.

“Why be bitter?” she said simply. “It doesn’t do you any good.”

She had never asked the Pentagon for any information on Ron. When I had pursued the matter, the Pentagon informed me that all the records of the 525 Military Intelligence Group in Hue had been lost. So, I asked her directly if she wished me to share with her what I found out from other, more direct sources.

“I guess I want to know everything you know,” she said without enthusiasm.

—

The headquarters of the intelligence group in Hawaii from which Ron had fled and to which I arrived in the summer of 1967 was on Ford Island in the middle of the vast naval base at Pearl Harbor. Its shoreline encompassed the famous “battleship row” that was the target of the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941, and the subsequent graveyard for the USS Arizona and USS Oklahoma. Since 1962 the USS Arizona Memorial has been one of Hawaii’s most visited sites. As it was with Maya Lin and Frederick Hart, the curricula vitae of the memorial’s designer, Alfred Preis, was surprising. He was an Austrian Jew who had converted to Catholicism and had escaped his homeland in 1939, landing in Hawaii only to be interned there as a Nazi suspect once the war began. His memorial sits above the sunken wreck of the battleship and is meant to resemble a bridge. But with its white exterior and its sagging center roof it has been likened to a “squashed milk carton.”

Preis’s description of the structure resonates for the Vietnam Memorial: “Wherein the structure sags in the center but stands strong and vigorous at the ends, [it] expresses initial defeat and ultimate victory … The overall effect is one of serenity. Overtones of sadness have been omitted to permit the individual to contemplate his own personal responses … his innermost feelings.”

USS Arizona Memorial (1962) by Alfred Preis, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii

The commander of our Hawaiian unit was a blustering, unpleasant, uncouth colonel, stuck in this faraway army outpost at the end of his career, after having been passed over for promotion more than once. Bald and crude, a veteran of World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, he had no college education. His passion was sports, and he seemed to live and die for his small unit’s performance on the dusty military ball fields of Hickam Air Force Base. Ron’s misfortune lay in being a natural athlete, and the colonel insisted that he star on the unit’s softball team. But Ron wanted to take courses at the University of Hawaii in his precious off-duty hours, and he refused to play. And so, the colonel harassed and tormented him, giving him kitchen and latrine duty and berating him in front of the troops. The tension grew worse and worse, until one day it became too much. After yet another violent quarrel over some trivial matter, Ron did the one thing that the colonel could not control: he volunteered for Vietnam.

With Ron long gone, I would have my own blowups with that gruff colonel. I too had been a pretty good athlete in high school and in college—All-Metropolitan in soccer and in baseball at my Washington, DC, high school, All-South in soccer at the University of North Carolina. So, I was the colonel’s next hot prospect to star on his softball team and his next victim for harassment, but I, too, had no interest in spending my free time in intramural athletics. The colonel exerted considerable pressure, and several times I came very close to following Ron’s lead in volunteering for the war. Perhaps they would send me to join Ron, and at last I would be doing the real work of intelligence. The lure of serving in the combat zone tantalized me as it had thousands of others. Duty stations in Baltimore, Monterey, and Hawaii did not sound so heroic. As the old saw goes, what was I to tell my grandchildren decades later about where I was during the Vietnam War? That simple juxtaposition, Ron’s experience and my own, is at the heart of Maya Lin’s artistic concept and power. When I look at Ron’s name etched in the black granite of her wall, I see my own face.

Ron’s first post was Da Nang, but soon enough he was reassigned to the Imperial City of Hue on the banks of the Perfume River. There he became “Mr. Reynolds,” dressed in civilian clothes, outfitted in a small one-story house with a latticed portico, on a dirt street barely broad enough for a jeep.

His letters back home to us were upbeat. He liked Vietnam. His words reeked of Graham Greene and evoked the romance we had all signed up for. I was envious. His detachment was known officially as the Field Sociological Study Group, and the outfit was supposedly “studying” the culture and sociology of Hue.

But Ron’s scholar-cover fooled no one—he was not the scholarly type—and eventually he was reassigned to a different job in Hue. He was now a “refugee employment liaison” to a US Navy employment office known as the Industrial Relations Division (IRD). His actual mission was worthy enough. The group was ordered to concentrate on the villages around Khe Sanh and in the A Shau Valley to the west of the city, through which a North Vietnamese invasion was sure to come, if there was to be one. They were to identify refugees whose hatred of the Viet Cong was great enough that they might be persuaded to return home to their villages as secret agents for the Americans. It was hoped that the agents would then provide “actionable” intelligence leading to productive combat missions for the twenty thousand US marines stationed nearby at Phu Bai.

Ron’s team of four was housed in a classy, French-style villa on Ly Thuong Kiet Street, near the Truong Tien Bridge over the Perfume River and across from the citadel and the historic Imperial Palace of Peace. The name of their road honored a Vietnamese hero who had won great victories against a huge army of invading Chinese in the eleventh century. If one is to believe the information in the Museum of Vietnamese History in Hanoi, Ly Thuong Kiet, a eunuch in the service of the Ly Dynasty, skilled in literature and martial arts, faced an enemy force of one million Chinese soldiers, supported by two million laborers, and 100,000 horses across the Cau River forty kilometers north of Hanoi. In a brilliant nighttime raid across the river, General Kiet crushed the invasion and ushered in an era of independence for Vietnam. With great certainty, the display reports that only 23,400 invaders limped back to China along with only 3,174 horses. Vietnamese children are taught a sacred song about Kiet’s glorious victory:

The land of the Viet people must be for the Viet king

That’s admitted by Heaven’s Empire

Why was it invaded?

The invaders would be sure to be defeated

Across the street from Ron’s tiny detachment was the ruin of the former United States Information Agency (USIA) library. It had been torched along with the nearby American consulate, in Buddhist uprisings against the South Vietnamese government a year-and-a-half before.

On January 30, 1968, the first day of the Lunar New Year, General William Westmoreland in Saigon was receiving strong indications of enemy movement around. As he later wrote, regulations required that the information be passed routinely through channels, going first to the Third Marine Division in Phu Bai. Somehow, the channels north from Saigon were clogged, unless the intelligence was simply ignored or disbelieved. The capable commanding general of South Vietnam army’s (ARVN) First Division, with its headquarters in the citadel, also had information of an imminent attack. On that day, to the dismay of his officers who were looking forward to a three-day holiday, he canceled all leaves and put soldiers under his command on full alert. American advisers including intelligence officers were integrated into ARVN command, but intelligence from that quarter did not make it across the Perfume River, much less to the boys on Ly Thuong Kiet Street at the end of the channel. So, the Americans knew the Tet offensive was coming. But this subsequent revelation of history did not help Mr. Reynolds. He went about a normal day, oblivious to the momentous event that was about to take shape all around him.

Had they been alerted and ordered to evacuate, the men of IRD could have thrown a few sensitive files into a shoulder bag and been on the road to Phu Bai in minutes. Or they could at least have sought refuge up the street in the small, walled American military compound of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV). It housed only about two hundred personnel, mainly administrative types and advisers, but no combat soldiers.

In the early evening, they strolled down to the river to carouse with the bar girls at a building known to the Americans as the Pink Pornography Palace, since it sported pre-World War I French pornographic images on the walls (although the women at another place called The Green Door were classier). Or if they were lucky enough to wangle an invitation to the Cercle Sportif on Le Loi Street, they might rub shoulders with old patrons from French colonial rule and ogle their graceful and beautiful women in white silk pants and tight high-collared tunics slit up to the hip. But at the down-low Pink Pornography Palace, they bought their favorite girl “Saigon tea” for less than a dollar, and a good deal of genuine flirting went on. (Had they wanted to take the flirting further, for an extra $15, they might have ended up with a girl on one of the sampans that floated languidly, awaiting them, in the middle of the Perfume River.) At the bar they might have burst into song, often an old standard composed by an American adviser in Hue that showed how a trooper with very little Vietnamese would communicate with a Vietnamese girl with very little English.

I walked into a bar, ’way down by the track.

There stood a young co dep, long hair down her back.

Her eyes, how they sparkled, in response to my touch

And she told me she loved me, she loved me too much.

Tai sao, tai sao, said she to me

Tai vy, tai vy, said I.

“In Saigon this morning, tonight I’m in Hue.

If the VC don’t get me tomorrow, makes one more day.”*

Into the evening, as they knocked down bottles of Ba Muoi Ba, Vietnamese beer named “33”—“the one beer to have when you’re having more than 33”—the conversation was relaxed and jovial. Perhaps there would be an attack on Hue someday, they mused. The enemy would sweep out of the A Shau Valley, take Hue, and then offer to negotiate. In the abstract, it was an interesting theory. But it did not translate into a premonition of imminent danger. Not now, not at Tet when there was always a three-day cease-fire between the sides to celebrate the holiday. And perhaps never. The North Vietnamese loved and respected the Imperial Capital too much, didn’t they? It was hallowed ground, the soul of Vietnam, the capital of Vietnamese emperors for centuries, the historical, cultural, educational, and religious heart for all of Vietnam. Thus, it was virtually undefended as an “open city.” Regulations forbade the use of heavy artillery or close air support within its confines. Hue was the moral equivalent of Kyoto, Japan, that had been spared American bombing during World War II because it was regarded as a global treasure.

At 3:40 a.m. Ron was startled awake by the sound of mortar passing over his house and landing near the MACV compound. The fluttering sound of larger shells followed shortly, 140 mm rockets. A few landed perilously close by. The bombardment lasted about an hour. To the west Ron could hear the crackle of machine gun fire, as flares lit up the sky. If the most effective NVA soldiers—called sappers—were actually going to attack, the team on Ly Thuong Kiet Street was sure they would have ample warning. At 4:30 a.m. there was a lull, and the men of IRD talked about walking over to MACV in the morning to inspect the damage. This was probably just another raid like those that had happened elsewhere in which the attackers returned to their jungle sanctuaries by daylight.

At 6:30 a.m. the scream of their guard—“VC! VC!”—shattered their serenity. Ron ran to the second-floor window. From there he could see only the ruined USIA library across the street. So, he scurried to the roof. From the west, already abreast of the CIA’s pacification compound, two files of North Vietnamese regulars approached. In each file, there were about twenty men, dressed in jungle fatigues and slouch hats. As Ron peeked out his window in the glow of dawn, the NVA soldiers walked by the house with scarcely more than a glance. Shortly afterward, a fierce battle broke out in front of the police station up the street, barely out of sight. It lasted about fifteen minutes.

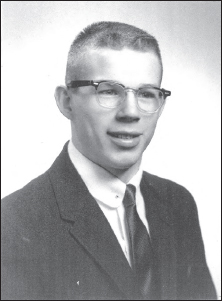

What Ron could not know was that these were the forward elements of the 804th Battalion of the People’s Army of Vietnam that was sweeping in from the south, while the even more fearsome 12th Sapper battalion was attacking in force from west of the city. Eventually, the NVA force would number 8,000 soldiers.

Map of Hue, Vietnam. The villa where Ron and his team were housed was on Ly Thuong Street, south of the Perfume (Huong) River, shown in bold.

At 10 a.m. the NVA attacked the South Vietnamese general’s house that lay directly behind a rice paddy and the IRD house. Backed by mortars and a machine gun that had been set up in the Catholic Church four hundred yards to the west, the North Vietnamese formed a handsome line and moved smartly across the paddy toward the general’s lair. At 1 p.m. hope sparked. In the distance from the southwest along Route 1, the road to Phu Bai, came the sound of tanks and trucks. Soon, the first American tank rattled into view, then two more tanks and twelve trucks. Ron could see US Marines walking behind the vehicles, but they were still the size of toy soldiers. The Americans inched forward, as Westmoreland put it in his memoirs, trying to relieve “the heroic little band that was still holding out in the MACV advisory compound.” As he watched these initial skirmishes from his roof, Ron might have imagined that he was watching a Hollywood movie. But as the fighting became more intense and devolved into urban combat, street by street, house by house—for which the Marines were not trained—the action was more reminiscent of World War II.

From his grandstand, as the senior officer, Ron took charge, directing the other three men to positions at various windows and crevices, and rationing ammunition and food. Sheer instinct ruled him. To his mates, he seemed to operate without fear, almost cavalier in this unimaginable danger, as if it were merely a piece of bad luck, and this was a scrimmage on his high school football field. More than once, one of his soldiers warned him to keep down, as he darted about the room on frog’s legs.

A half hour later, as he was parceling out ammunition to others, a sniper bullet smashed through the window and shattered his liver, passing through his side, and out his belly. He bled little. His pulse and breathing subsided rapidly. It was said later that he did not suffer. He had not fired a shot. For him there had been no heroic charge up a forgotten jungle hill, no fierce combat in a remote rice paddy. Just a random bullet. Finito.

—

Back at the Veterans Day ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, the band played. Prayers were read before a broad-chested brigadier general in full regalia stepped forward to render words of comfort. Without much delay, he gravitated to the old well: Abraham Lincoln’s letter to Mrs. Bixby, the mother of five dead soldiers.

“I feel how weak and fruitless must be any words of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. …” I can’t remember what else the general said, except his banal closing line.

“Thank you for being players in Americanism.”

When it was over, I bade Ron’s mother farewell. I would not be going with her to the wreath-laying at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, nor to another ceremony with more minor dignitaries at the Vietnam Memorial. I preferred to visit Ron alone, later, without others making their dishonest uses of him. We lingered for a long handshake.

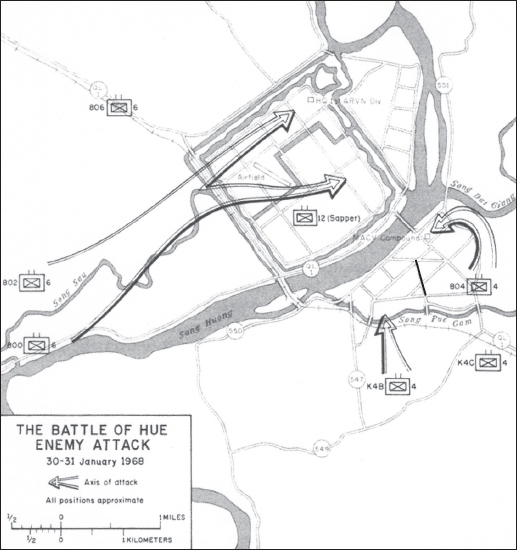

The name of Ronald E. Ray on Panel 35E of the wall

“Well, what did you think?” she asked. I muttered something.

“Don’t shrug,” she said maternally in gentle scold, and we shared a smile of understanding.

His Bronze Star citation read:

A large North Vietnamese Army force overran much of the city late on January 30, 1968, and Sgt. Ray’s small unit was cut off from friendly military support. The enemy forces quickly discovered his team’s position and attacked it. Time after time, Sergeant Ray exposed himself to ravaging enemy fire to repel the determined insurgent assaults with fierce rifle and grenade fire. The team’s furious fighting diverted enemy troops from their primary targets and was far above the resistance to be expected from such limited manpower and weaponry. While fearlessly leading his men in a staunch defense of their position, he was hit by sniper fire and instantly killed.

Perhaps in memory that was the way it was, or should be.

—

I came to believe that there might have been a consolation in the suddenness of Ron Ray’s demise. In all probability, a more gruesome fate was in store for him, had he survived the first night of Tet. It became known later that, from their extensive network of informants, the Communists knew exactly who was living in the French villa along Ly Thuong Kiet Street and what they were doing. In fact, blithe spirit that he was, totally innocent of the danger he was in, Ron stood out. What else could he be but an American intelligence agent? Of the twenty Americans who were living their apparently charmed life outside the MACV compound, only two survived. One of those did so by hiding in the muck of a pigsty for several days as scores of NVA soldiers passed by, holding their noses. The body of another American working outside the walls of a military compound, a USIA official, was soon discovered several days after January 30 with his hands tied behind his back and a bullet hole in the back of his head. He was only a harbinger.

Assassination squads, with lists of names, fanned out across the city and began their task of savagely eliminating their enemies, targeting political leaders, city officials, civil servants of the “puppet regime,” as well as teachers, policemen, and intellectuals, and the few exposed American operatives like Ron, who were easy prey. For the most part, the assassins were local Viet Cong cadre, but they were assisted by North Vietnamese regulars. Perhaps upwards of 2,800 people were killed in the four weeks the NVA occupied the city. Their bodies were dumped in a mass grave. Only months later were the corpses exhumed and given a decent burial. In terms of face-to-face murder of civilians, the Hue massacre in February 1968 was the worst atrocity of the Vietnam War.

Meanwhile, the beleaguered MACV compound was able to hold out against a determined assault, until US Marines fought their way up Route 1 to rescue it. Ly Thuong Kiet Street became a strategic battleground with NVA soldiers occupying every house. Some of the fiercest fighting took place along that thoroughfare. For days the sound of tank, recoilless rifle, and heavy machine gun fire resounded through the street, as Marines sought to clear each house and each room of its North Vietnamese defenders. But the Americans paid a high price. In the month-long battle, one of the bloodiest of the war, the three Marine battalions that fought sustained a 50 percent casualty rate; 216 American soldiers were killed and 1,609 were wounded. Five thousand attackers perished, and military historians regard their inability to capture the MACV compound as a major factor in losing the battle.

The death of Ron Ray was merely a mundane footnote to a far larger struggle.

In the battle of Hue, and in the Tet Offensive that launched attacks against more than a hundred cities and towns, America lost its will to prosecute the war. Only a few months before, in November 1967, General Westmoreland had come home to assure the American people that the tide had turned and the war at last was being won. But after Tet, CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite went to Hue and made a crucial observation.

“We have been too often disappointed by the optimism of the American leaders, both in Vietnam and Washington, to have faith any longer in the silver linings they find in the darkest clouds. … We are mired in a stalemate,” that can only be ended by negotiation, not victory.

Meanwhile, Hue itself, that exotic, once tranquil, romantic, untouchable cultural jewel, lay in ruins. Of its 140,000 citizens, 116,000 became refugees.

In a matter of terrible bad luck, Ron Ray found himself, unwittingly and tragically, at the center of decisive historical events, but somehow that is cold comfort indeed. It is hard for me to believe that what he was doing in that little villa mattered very much. If he was a candidate for Maya Lin’s wall, merely one of 58,000, he would not easily have seen his image reflected in Frederick Hart’s soldiers, unless it was that awe-struck, thousand-yard stare down Ly Thuong Kiet Street in terror and hope, which he must surely have had in his final, harrowing hours.

—

I am sitting at a tea house beside the Hoan Kiem Lake in the Old Quarter of Hanoi. At last the week-long rain has stopped, and a full moon is rising through the mist. I’m waiting for Dr. Nguyen Ngoc Hung, a professor of English, a former government minister of education, and veteran of the battles around Hue. And for Bao Ninh. Ninh is Vietnam’s most famous writer and the author of an astonishing, phantasmagoric novel called The Sorrow of War. When it was published in England in 1993, the Independent hailed the book as a masterpiece, saying it “vaults over all the American fiction that came out of the Vietnam War to take its place alongside the greatest war novel of the century, Erich Maria Remarque’s classic, All Quiet on the Western Front.”

These have been interesting days. They began with a trip to the old dividing line between North and South, the former DMZ, the most militarized “demilitarized zone” ever, and probably one of the most heavily bombed landscapes in the history of the world. My guide was Chuck Searcy, an ex-military intelligence officer like myself, who has lived in Vietnam since 1995 and has devoted himself to the overwhelming task of defusing unexploded ordnance, especially tennis ball-sized cluster bombs (now internationally banned) that are so attractive as playthings to children. His work is a kind of personal atonement for the sins of his country. American planes dropped more than eight million tons of bombs on Vietnam during the war, and the danger persists. Ten percent of those were unexploded. More than eight thousand deaths have resulted from delayed explosions.

Truong Son Cemetery, Vietnam

Chuck had taken me to see the network of tunnels north of the Ben Hai River—the dividing line between North and South Vietnam—where villagers and North Vietnamese guerillas lived underground for years. From there we drove many miles through heavy rain, dodging children and cows, past flooded rice and cane fields to the Truong Son Cemetery, North Vietnam’s equivalent of Arlington National Cemetery. Only a fraction of the one million NVA and VC dead are buried and memorialized there.

Sculptures in the mode of Soviet realism greet the visitor to the national cemetery. In the ornate pagodas that appoint the corners of the sacred burial ground, the names are engraved on black granite plaques. They remind me of a line in Bao Ninh’s novel: “The fallen soldiers shared one destiny; no longer were they honorable or disgraced soldiers, heroic or cowardly, worthy or worthless. Now they were mere names and remains.”

Statuary as “entrance experience,” Truong Son Cemetery, Vietnam

Inevitably, I’d visited the Hòa Lo Prison Museum, the notorious “Hanoi Hilton,” and read with interest the inscription on the wall outside the two rooms devoted to the American War, as the Vietnamese call it: “During the war the national economy was having difficulties, but the Vietnam government created the best living conditions they could for US pilots. They had a stable life during their temporary detention periods.” A video portrayed the happy prisoners playing volleyball and ping pong. But in that prison museum the brutal French colonial occupation of the country is far more emphasized, including a grotesque guillotine that was regularly employed against resistance leaders. At first, I took the understatement as a sign of historical softening, driven by the newfound friendship between the United States and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. I had heard that there was even a move afoot in the Politburo to change the name of Liberation Day—April 30, the date Saigon fell—to Unification Day.

If American transgressions are downplayed in Hanoi, nothing is glossed over at the gruesome War Remnants Museum in Saigon, formerly known as the American War Crimes Museum. The graphic, unrelieved portrayal of American massacres, tortures, poisonings, and bombings there is gut-wrenching, deeply upsetting, and profoundly sad. And yet even those pictures on the museum wall and the evocative plaques cannot put the viewer into the “jungle of screaming souls,” the way Bao Ninh had done in his novel’s description of what it was like to be on the ground when American helicopter gunships or napalm-bearing F-4 jet fighters or B-52 bombers were overhead. War, he wrote, was a world without romance. His protagonist, Kien, says of himself that it was “hard to imagine, hard to remember a time when his whole personality and character had been intact, a time before the cruelty and the destruction of war had warped his soul. A time when he had been deeply in love, passionate, aching with desire, hilariously frivolous and lighthearted, or quickly depressed by love and suffering. Or blushing in embarrassment. When he too was worthy of being a lover and in love.”

Meanwhile, old Saigon is in the grip of Wild West Capitalism. Amid a forest of construction cranes, high-rises sprout across the city’s landscape. There is even an impressive thirty-five-story skyscraper on the Saigon River, designed by César Pelli, Maya Lin’s mentor at Yale. In the final stage of design, Pelli was encouraged to “Vietnamize” his building by adding a spire, evoking the hat of the Hung Kings, the founders of the nation in the year 2879 BC.

But mainly, I’d come all the way to Vietnam on a pilgrimage to Hue. There I’d holed up in an unpretentious hotel along Ly Thuong Kiet Street. The hotel promotions had promised a “nice clean hotel, nicely decorated, great food, friendly staff that speaks English well.” That last part about speaking English well did not exactly turn out to be the case. My corner room on the seventh floor looked down on a vacant lot at the intersection of Ly Thuong Kiet Street and Dong Da Street where once an American consulate stood, before a thousand Buddhist students burned it down on June 1, 1966. That is how it was reported back then. Now we know that many of those “students” were Viet Cong. After all, Ho Chi Minh had lived undercover as a Buddhist monk in Bangkok for four years from 1921 to 1925.

Vietcombank Tower (2015) by César Pelli, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

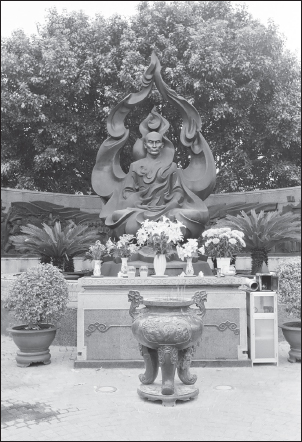

And in old Saigon, there is a shrine to Thich Quang Duc, the Buddhist monk who burned himself publically in 1963 and sparked the Buddhist Revolt against the Americans and their “puppet regime.” It is widely supposed in Vietnam that Thich Quang Duc was a Viet Cong in monk’s clothing. The English roadster that he drove from Hue to Saigon is preserved in the Hue pagoda as an artifact of his gruesome political suicide. Why would an atheist Communist state elevate a holy man to such heights of heroism, except for his service to the National Liberation Front?

It is remembered that the First Lady of South Vietnam, the notorious Madame Nhu (known as the Dragon Lady) had said before his immolation, “Let them burn, and we shall clap our hands.”

Memorial to Thich Quang Duc, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Dr. Hung arrived alone, apologizing that he had been unable to reach his friend, Bao Ninh, who had apparently dropped out of sight and thrown away his cell phone. He had had enough of the taunting of other Vietnamese writers who were jealous of his international fame and of the Vietnamese government that had banned his book for ten years and now was denying him its highest literary prize. I was only mildly disappointed. I had heard that, despite his literary mastery, Bao Ninh in person was shy and incommunicative. Dr. Hung, white-haired with an oval brown face, a gentle affect and thoughtful manner, had earned a PhD in Australia, and his fluency was a great relief to me.

I told him I had seen the shrines: the tunnels in Viet Moc and Cu Chi, the museums in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, the heroic statue of Thich Quang Duc, the tiger cages of the Con Son Prison. If collective fury existed, it seemed to be more directed against the Chinese and the French than the Americans. Among the people, as far as I could tell, there was no gloating about victory over the United States. Why was it, I asked him eventually, that there is so little triumphalism in Vietnam?

For an answer to that, he replied, you have to go deep into history. For a thousand years the Chinese invaded Vietnam, coming every thirty to fifty years to plunder this country and make it a vassal state. Then the French came for a hundred years with their arrogant quest to “civilize” the country through their brutal colonialism. After they left in 1954, there was only a brief respite before you came to impose your American brand of freedom and democracy. You stayed only fifteen years.

But why, I persisted, after all the bombing, several million deaths, and the poisoning of the land, was there not more anger and resentment?

Because, he replied, we fought the war differently than you. You measured success by how many soldiers you killed and how many weapons you seized. We lost every battle. Whenever thirty of us went out on an ambush, we were lucky if fifteen returned. But it was never our intention to defeat you. Indeed, 1968, the year when your friend was killed, was the worst year for us. There were no soldiers left, and the government had to scrape the barrel to find more men like me, students and women. But we fought only to make the Americans go away.

Why don’t I see images of valiant heroic fighters everywhere? I asked. Because, he answered, we do not glorify soldiers. We remember the suffering of the women for their husbands and their sons. You will find no Rambos here. We only go to war when we can’t avoid it. Our patriotism is like a lump of charcoal. When it is left alone, it is dormant and harmless. If you light it, it burns very hot. It can start a big fire and spread rapidly until it consumes a whole forest. But when it is over, it is over, and we focus on peace and development and rebuilding.

He looked out on the lake. This lake is called Ho Hoan Kiem, he said, and a legend is associated with it, the Legend of the Returned Sword. In 1428 a fisherman came here, and from the depths, a tortoise emerged and handed him a magical, golden sword from Heaven. On its simple wooden handle was written: “To Save the Nation.” The fisherman became a great man, an emperor, to defend Vietnam against invasion from the Ming Dynasty of China. After many years, this king prevailed against the Chinese. After his victory, he returned here to this lake, magical sword in hand, and a giant golden tortoise surfaced from the depths and snatched it away, restoring it to its divine owners and leaving the king with only its wooden handle. The war was over. The sword was now useless.

We are proud of this legend, Dr. Hung said. Its message is deep in our culture and our character.

I thanked him for his time, and we parted with a warm handshake, and I watched him fearlessly navigate across the busy thoroughfare, through the swarm of motorbikes, without a backward glance.

*Translation: co dep: pretty girl/“too much” to a bar girl means “a lot”/ tai sao: why?/tai vy: because.